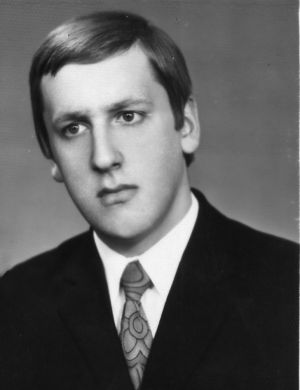

ROMAN STEPANOVYCH KALAPACH (born November 12, 1954, in Stebnyk, Drohobych raion, Lviv oblast).

Leader of a patriotic youth group, entrepreneur, public figure.

His family participated in the national liberation struggle. His mother’s brother, Emiliya Trach, died in 1943 in the UPA, and her sister Maria was imprisoned for her involvement in the underground.

From childhood, Roman read Ukrainian publications from the Polish era and, by the age of 12, was consciously distributing leaflets.

In 1970, while in the 10th grade at School No. 7, Roman gathered about a dozen young men who were ready to fight for an independent Ukraine. Their first goal was to obtain higher education. The following year, new tenth-graders joined them.

Since Soviet propaganda had declared the national question resolved once and for all, Roman proposed to his friends during a meeting that they raise yellow-and-blue flags in Stebnyk on May 1, 1972, to show that there were people fighting for an independent Ukraine. With money collected by the group, he bought yellow fabric in Lviv, but could not find blue fabric by May 1. Then Lyubomyr STAROSOLSKYI suggested taking down the flags of the Ukrainian SSR to use the blue part for the Ukrainian flag, but they failed to do so on May 6, as there were too many people on the streets. On the night of May 7, Roman and Zinoviy Dmytriv managed to tear down two flags.

On the night of May 9, in the attic of his neighbor Petro Yaruniv, Kalapach and STAROSOLSKYI hand-sewed two Ukrainian flags. That same night, they hung one flag on the balcony of the “Shakhtar” House of Culture and the second in the city center on a flowerbed, after removing the flag of the Soviet Union. To ensure the flagpole fit tightly into the metal pipe, they wrapped it with copper wire.

In the morning, KGB agents and police arrived, but seeing the wire, they were afraid to take down the flag and called sappers. By 2 p.m., many people had come to see the flag.

The director of the House of Culture had taken down the flag in the morning but was afraid to report it anywhere and hid it under the podium.

Drohobych KGB agents, led by Vasyl Zaderey, and later by Major Kharitonov of the KGB sent from Kyiv, interrogated several hundred former political prisoners living in Stebnyk but could not find the culprits. Meanwhile, the case gained wide publicity. A meeting was convened at the House of Culture where citizens were urged to help identify the “criminals.” It was then that the director produced the blue-and-yellow flag from under the podium…

The youths were traced as follows. A tenth-grader, Volodymyr Pikas, forgot a notebook at school with a list of foreign radio station frequencies. The school director, Isaak Kamsa, took the notebook to the KGB. Suspicion fell on Lyubomyr STAROSOLSKYI and Mykhailo Kulyk. They were given failing grades for conduct, barred from their final exams, and expelled from school (only two teachers opposed the expulsion).

To divert suspicion from STAROSOLSKYI and Kulyk, Kalapach decided to post leaflets in Stebnyk and Drohobych. But his accomplice told his father about it. The father, hoping for the release of his elder son from criminal imprisonment, revealed the intentions of his younger son and his accomplices to the KGB.

In the first days of August, the young men began to be summoned for questioning by the KGB. STAROSOLSKYI was detained for 2 days. By then, Kalapach had already passed his first exam for the law faculty of Lviv University. During the second exam, he was called to the admissions office—and led out in handcuffs, then taken to the KGB. He was interrogated for three days, spending the nights in a hotel under guard. Believing that the youths were being directed by someone older, they were released on their own recognizance in order to monitor their connections.

Kalapach got a job as a worker at “Stebnykprombud.” He was already psychologically prepared for imprisonment, regretting only that he had been caught so early. He was arrested on February 9, 1973, in Stebnyk and taken to the Lviv pre-trial detention center.

His father found a well-known lawyer for his son, but the lawyer said: “Mr. Kalapach, if your son, God forbid, had killed someone or stolen something, I would defend him, but in a political case, I can do nothing.”

On February 18 and 19, 1973, many people stood outside the Lviv Regional Court building, but only the closest relatives were allowed into the courtroom. Prosecutor B.I. Kolomiyets demanded that Kalapach be sentenced to 6 years of imprisonment in a strict-regime camp, and STAROSOLSKYI to 5 years, under Article 62, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”), as well as under Article 187-2 for “desecration of a state flag.” Lawyers A.A. Dyatlova and M.V. Polishchuk argued that minors could not be sentenced to more than 3 years.

The court, presided over by I.Yu. Khomyuk, sentenced Kalapach to 3 years of imprisonment in a strict-regime camp and STAROSOLSKYI to 2 years in a general-regime camp under Article 62, Part 1, and both were also sentenced to 1 year under Article 187-2. Upon reaching the age of majority, the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR changed STAROSOLSKYI’s regime to strict. Zinoviy Dmytriv, Petro Yaruniv, and Mykhailo Kulyk were questioned as witnesses and released into the custody of “labor collectives.”

In April 1973, Kalapach was transported to the strict-regime camp VS-389/35 at Vsekhsvyatskaya station in the Perm oblast. Here he befriended old insurgents, particularly endearing himself to Stepan Yasnytskyi and Vasyl PIDHORODETSKYI. He was on good terms with Ihor KALYNETS, Mykola HORBAL, and Andriy KOROBAN. He was treated kindly by the communities of Jews, Lithuanians, and Russian democrats (including Vladimir Bukovsky).

Within a week, he learned to be a lathe operator and was not concerned with material conditions, as there was at least enough bread in the camp at that time. He studied German.

Kalapach was released on February 9, 1976. He was not under official administrative supervision, although he was constantly monitored. For 7 years, Kalapach worked as a lathe operator at the Potash Plant in Stebnyk.

At the age of 24, he married Yevheniya Yandzhak, from a family of the repressed. They have two daughters, Maria (b. 1979) and Anna (b. 1985).

From 1982, he worked at the mine as a miner and timberer, and from 1985, in the mine rescue team of the Stebnyk Potash Plant.

In 1982, he enrolled in correspondence courses at the Kryvyi Rih Technical College of Mining Automation, which he completed in 1984. In 1986, he entered the correspondence department of the mining faculty of the Drohobych branch of the Dnipropetrovsk Mining Institute, earning a degree as a mining engineer.

He is a founding member of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons (1989).

In the center of Stebnyk in the spring of 1992, a memorial sign was unveiled with the inscription: “Here, on May 9, 1972, the national flag was raised,” but without the names of the young men, as they did not wish to be immortalized. They were rehabilitated that same year. In the early 1990s, there were a number of publications in the local press about the heroic act of the youths, particularly in the newspaper “Frankova krynytsia.”

The mayor of Drohobych, Myroslav Hlubish, proposed that Kalapach create the first private trade and production enterprise. Kalapach named it “Roksolana” and has been its director since 1992. He supports the activities of many Ukrainian organizations and conducts charitable actions for the benefit of orphans and patriotic youth organizations.

In 2002, he was elected a deputy of the Drohobych City Council, serving as secretary of the commission on privatization, industry, and investment. In 2006, he was elected mayor of Stebnyk and served until October 2008.

By a decree of the President of Ukraine dated November 26, 2005, he was awarded the Order “For Merit,” III class, “for his significant personal contribution to the national and state revival of Ukraine.”

Bibliography:

Kasyanov, Heorhiy. Nezhodni: ukrayinska intelihentsiya v rusi oporu 1960-80-kh rokiv. – Kyiv, Lybid, 1995. – p. 142.

Pastukh, Roman. Stebnytski lomykameni // Drohobychchyna – zemlia Ivana Franka. – Drohobych: “Vidrodzhennia” publishing firm, 1997. – pp. 417 – 418; also p. 83.

KHPG Archive: Interview with R. Kalapach, recorded by V. Ovsiyenko on February 2, 2000; interview with L. Starosolskyi on January 28, 2000.

Matsiv, Viktor. Z kredytom doviry. Roman Kalapach vdykhne u Stebnyk nove zhyttia // Drohobytskyi portal, February 17, 2006.

Roman Kalapach – miskyi holova m. Stebnyk. http://who-is-who.com.ua/bookmaket/lvov/2/13.html

Prepared by V. Ovsiyenko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, July 8, 2005; July 21, 2009.