One of the most powerful dissident movements in the USSR was the Crimean Tatar Movement for the Return to Crimea.

On May 18, 1944, an entire people—the Crimean Tatars—was accused of treason and deported from Crimea. The special settlements for Crimean Tatars were in Uzbekistan, Turkmenia, Kazakhstan, Kirghizia, the Urals, and the North Caucasus. The largest number of Crimean Tatars was in Uzbekistan. It was from here that the Crimean Tatar movement for the return to their homeland began, awakened by the Thaw. Its initiators were Crimean Tatar communists, veterans of war and labor, who, after the condemnation of Stalin’s personality cult, tried to draw the authorities’ attention to one of his atrocities—the deportation of the Crimean Tatars—and to restore historical justice. Their only form of struggle was petitions, written in the spirit of the official rhetoric of the time, supporting the Party’s new course and condemning Stalin and his slander against the Crimean Tatar people. At the same time, the activists of this movement agitated among their people for a return to Crimea, collected signatures, and called for appeals to government structures. In villages, districts, and cities, initiative groups emerged. By the early 1960s, more than 100,000 people were signing the petitions. This showed that the Crimean Tatar movement had become nationwide. However, the authorities remained deaf to the pleas of an entire people. In the early 1960s, repressions began. They led to a decline in petition campaigns. However, from 1964, the Crimean Tatar movement, reinforced by young, educated, and resolute people, transitioned to a more active struggle. Mass rallies and demonstrations by Crimean Tatars began. They were held in the spirit of the times on Soviet holidays, especially on Lenin’s birthday, with all the corresponding paraphernalia but with bold speeches and demands. The Crimean Tatars also commemorated the day of deportation, May 18. They mourned those who died during the resettlement, wore mourning clothes, and even hung black banners on administrative buildings at night. The Crimean Tatars believe it was because of their actions that the infamous Article 190 of the RSFSR Criminal Code and its analogues in other republics were introduced into the criminal codes. Activists of Crimean Tatar mass events began to be summoned to the police or to Party bodies, where the content of the new article and its three parts was explained to them: “slander against the Soviet system,” “desecration of the coat of arms and flag,” and “mass riots,” hinting at their possible application.

However, the new wave of the movement grew. In 1966, movement activists conducted a nationwide survey to establish the population size and the number of deportation victims. The results were sent to the 23rd Congress of the CPSU in an appeal signed by 130,000 people. In October 1966, mass rallies were held in connection with the 45th anniversary of the formation of the Crimean ASSR. These rallies were dispersed by the police and the army, and dozens of their participants were sentenced under articles analogous to Art. 190-3 of the RSFSR Criminal Code.

The active efforts of the Crimean Tatars eventually led the authorities to make concessions. On September 9, 1967, two Decrees of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR were issued: “On Citizens of Tatar Nationality Formerly Residing in Crimea” and “On the Procedure for Applying Part 2 of the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of April 28, 1956.” The aforementioned 1956 Decree lifted the special settlement regime from the Crimean Tatars but forbade them from settling in Crimea. The new Decrees, although they humiliated the national dignity of the Crimean Tatars with formulations like “citizens of Tatar nationality,” nevertheless removed the stigma of “traitors to the homeland” and allowed them to settle “throughout the entire territory of the USSR,” including Crimea.

However, as is well known, in the Soviet Union, the law and its application were two very different things. From the moment the Decrees were issued, the second stage of the Crimean Tatar people’s struggle for their return to the homeland began, which is directly related to the history of Ukraine. The authorities meticulously prepared for the Crimean Tatars’ attempts to settle in Crimea. Even before the Decrees were published, a propiska (residence permit) system, which had previously existed only in cities and resorts, was introduced throughout Crimea. Notary offices were given a secret directive not to process the purchase of houses if the buyer was a Crimean Tatar, and heads of enterprises were ordered not to hire Crimean Tatars, despite a labor shortage on the peninsula. The result of this discrimination was that in 1967, out of the first wave of repatriates, which consisted of about 1,200 Crimean Tatar families, only two families and three unmarried men were able to legally settle in Crimea.

In 1968, it was announced that the entry of Crimean Tatars into Crimea would be carried out through organized recruitment. But in this way, only “obedient” citizens who had not actively participated in the movement and had not signed any statements or appeals were allowed to enter. The repatriation of Crimean Tatars outside of organized recruitment also continued, but its results were not much different from 1967. By 1979, 15,000 Crimean Tatars had moved to Crimea, which was less than 2% of their total number. And after 1979, thanks to various discriminatory and repressive measures, the number of Crimean Tatars who settled in Crimea did not increase at all until Perestroika.

Those who could not obtain a residence permit, find work, or formalize the purchase of a home were forcibly evicted from Crimea, sometimes with brutal physical force. Houses were demolished, and many Crimean Tatars were tried for violating the passport regime. At the same time, the authorities obstructed peaceful rallies and holidays of the Crimean Tatars in exile, and in some places, such as in Chirchik in 1968, they were dispersed, brutally beaten, 300 people were arrested, and 10 of them were sentenced to various terms. The same happened to the delegates from the Crimean Tatars who came to Moscow to protest against the actions of local authorities. Roundups of Crimean Tatar representatives in Moscow and their expulsion from the capital became a regular practice of the repressive organs.

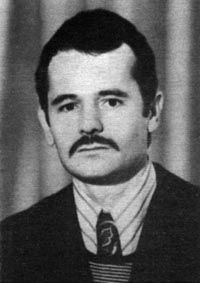

In 1968-1970, repressions against active participants of the Crimean Tatar movement significantly intensified. In September 1968, the 10 most active members of the initiative groups, who compiled information bulletins and drafted nationwide appeals, were arrested. The Crimean Tatars supposedly turned to Petro Hryhorenko with a request to be a public defender at the trial, which was expected in May 1969. In reality, it was a KGB provocation. On May 7, 1969, he was arrested in Tashkent. Hryhorenko was declared mentally ill and spent five years in a special psychiatric hospital. On May 17, another defender of the Crimean Tatars, Ilya Gabay, was arrested. By this time, the Crimean Tatar movement was already closely linked to the all-Union human rights movement. Prominent human rights activists such as Petro Hryhorenko, Aleksei Kosterin, Ilya Gabay, Dina Kaminskaya, Sofiya Kallistratova, and others were concerned with the problems of the Crimean Tatars. They spoke out in defense of individual representatives of the movement and against the terrible injustice of the Soviet authorities towards the entire Crimean Tatar people. As L. Alexeyeva notes, these relations were not one-sided: “At the moment of convergence, the human rights movement was only in its formative stage, with almost no experience, while the Crimean Tatar movement had a history of more than 10 years and there was much to learn from it.” In particular, according to Natalya Gorbanevskaya, the first editor of A Chronicle of Current Events, the source of this publication was precisely the information bulletins of the Crimean Tatars. Similarly, the Initiative Group for the Defense of Human Rights, which emerged in Moscow in 1969, was created on the model of the Crimean Tatar initiative groups. One of the founders of the Initiative Group for the Defense of Human Rights was Mustafa Dzhemilev, an activist of the Crimean Tatar movement, a dissident, a political prisoner, who later became a national hero and led the Crimean Tatar movement for repatriation. On September 11, 1969, he was also arrested. He was tried together with I. Gabay. Both were sentenced in January 1970 under Article 190-1 to 3 years of imprisonment. Mustafa Dzhemilev dedicated his entire life to the national struggle; he was first tried in 1966, then in 1970, 1974, 1976, 1979, 1983, and for the last time in 1986. From 1970, as noted by researchers of the movement’s history and its representatives, the Crimean Tatar movement went into decline, but it never ceased.

The Crimean Tatar movement for the return to Crimea was the most massive dissident movement in the USSR—the actions of this movement alone numbered hundreds of thousands of participants. It played a major role in the struggle against Soviet totalitarianism.