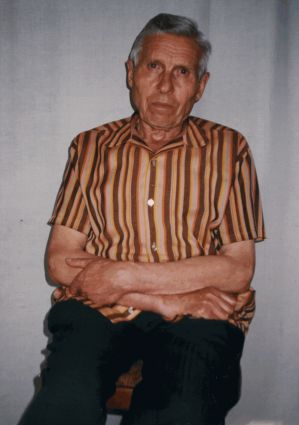

A peasant and worker. Twice repressed for defending his economic interests and human rights, and for his national consciousness.

From a peasant family. His mother, Tsiruk Motrya Dorokhteivna (June 23, 1908 – November 22, 1995), was illiterate and worked for wealthier people from a young age. Her father, a farmer named Dorokhtei Tsiruk, received 14 desiatinas of land for his family of 14 in 1922, which he cultivated with his family. On Christmas Eve 1932, he was “dekulakized.” One of the dekulakizers shook out little Mykola’s embroidered shirts and shouted, “Buy the kulak’s things, buy the kulak’s things!” His mother wrapped Mykolka in an old svytyna (a traditional outer garment) and took him to his father-in-law, Matviy Polishchuk, in the village of Haivoron, where he spent his childhood. In 1933, 470 people died of starvation in Haivoron—and that was just on the right bank of the Berezna River. There were cases of cannibalism. His father, Polishchuk Kindrat Matviyovych (1904–1943), did not join the kolkhoz. During the 1934 harvest, his father and mother reaped their own rye, for which activists threw them into the “kholodna” (a cold cell or lockup), confiscated their harvest, and marched them under guard, along with other “shytrafnyky” (penalized workers), to harvest the kolkhoz fields.

In 1938, when Mykolka started first grade, the children of activists beat him for being the son of an odnoosibnyk (an individual farmer who refused to join the collective). He spent several months tied down in a plaster trough at the Vasylkiv children's sanatorium. Maggots developed under the cast…

Due to an accident involving his sister Hanna (b. 1936), in 1940 his mother failed to complete the minimum of 11 trudodni (workday units), and since his father did not work on the kolkhoz, their household was expelled from the collective, subjected to double taxation, and had their garden plot taken away. In 1941, a month before the war, all their property was inventoried for non-payment of taxes, but it was not confiscated in time. During the German occupation, at least they did not starve. His father was killed in December 1943 while crossing the Dnipro River.

In March 1944, Mykola entered the third grade and finished his seven-year schooling in 1948. The young man desperately wanted to escape his mother's difficult situation, and in August 1948, he went to Skvyra and passed all the exams for the agricultural technical college in one day. He walked to the college barefoot, caught a cold, and that was the end of his education. He worked on the kolkhoz as a gardener's apprentice, then around the clock as a milk recorder, earning 0.75 trudodni, and later as a general laborer on par with able-bodied men. He drew the kolkhoz wall newspaper. Confident that the “kulak’s son” would not be accepted, he unexpectedly joined the Komsomol on a dare with friends.

In 1952, he moved to the Donbas, where he worked as a guard at the Kirov plant in Makiivka, as he could not pass the medical examination to be hired as a worker. He enrolled in the 8th grade of an evening school. The instruction there was in Russian, so his studies were initially difficult. He was outraged by the total Russification: in 1955, at a Komsomol meeting, Polishchuk took the floor without permission and said: “Here I could not find a Ukrainian school, here the Ukrainian language is oppressed, and even at Komsomol meetings, I cannot express my thoughts in Ukrainian. Do I have no future here?” And he placed his Komsomol card on the table. He was expelled from the 10th grade for asking his teachers uncomfortable questions.

At his mother's request, he returned to Haivoron in 1955 because his stepfather had been killed by a truck while hauling beets, leaving behind a cow, a beehive, and an old house. Mykola worked in the kolkhoz construction brigade alongside able-bodied men. He enrolled in correspondence courses at the Rzhyshchiv Construction Technical College, graduating in February 1964. He wrote his term paper on structural statics in Ukrainian but had to translate it into Russian. There was no work for him in the village in his field of study; as a disabled person, he was given exclusively hard physical labor. In 1962, he fell from the loft of a cowshed and spent 17 days in the hospital. For failing to meet the minimum trudodni, he was taxed at a 50% higher rate. He clashed with the kolkhoz chairman, Otamanenko, a “thirty-thousander.”

From 1963, Polishchuk did not participate in elections. When the CPSU adopted a policy of consolidating raions and kolkhozes, Polishchuk spoke out at a meeting against merging his kolkhoz with a neighboring one. The peasants prompted him on what to say but remained silent themselves. Two weeks later, a policeman warned him that he was about to be charged with hooliganism (Article 206 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR). Polishchuk went to Kyiv to find his deputies, Synytsia, the secretary of the Kyiv Oblast Party Committee, and O. Ye. Korniychuk. He couldn't find the former, and Korniychuk's wife said her husband would not see him. He went to the Kyiv Oblast Prosecutor's Office. There, Deputy Prosecutor Rusanov berated him for speaking out against the “party line,” and the next day he came to Haivoron for an expanded kolkhoz board meeting, where he organized a “public condemnation” of Polishchuk and accused him of preventing the kolkhozniks from building communism. In the kolkhoz chairman's office, he said: “You see you have no friends here, don't you? You see. So here's my advice to you: get out of here. They'll give you good papers—just get out.” Polishchuk said he did not want to leave the village, as he had just finished building his house and had five beehives. – “You'll have no life here—and your house will be gone, and nothing will be left. Just get out of here.” A year later, they finally convinced him that he would be imprisoned for “parasitism.”

In 1965, Polishchuk moved to Bila Tserkva. He worked in many construction organizations as a laborer, foreman, and senior department engineer, performing complex engineering calculations for enterprises. He earned well-deserved respect for his conscientious attitude toward his work and was a trade union group organizer. He did not tolerate falsehoods, fraudulent reporting, or abuses by his superiors. He lived in trailers and in seven different dormitories before finally receiving a one-room apartment on March 9, 1972.

Polishchuk traveled to Kyiv libraries, took an interest in cultural events, and bought the newspaper “Visti z Ukrainy,” from which he learned about Ivan DZIUBA and his work “Internationalism or Russification?” In September 1969, he wrote a letter to the editor of “Visti z Ukrainy” on this topic. In June 1973, he sent a letter to the editor of the newspaper “Literaturna Ukraina” about the state of the Ukrainian language.

During a tourist trip to the Caucasus in 1974, Polishchuk again did not vote. That year, he was officially warned that if he did not stop spreading slander against the Soviet state and social system, he would be prosecuted. On the warning, he wrote that he had not slandered the Soviet government in any way. A KGB agent told him: “It would be better if you were a womanizer, better if you were a drug addict, better if you were a drunkard, but not a chatterbox. Mark my words, you won't get away with this.”

In October 1974, Polishchuk transferred to a military unit for a position as a senior engineer, but on December 9, 15 minutes before the end of the workday, he was fired without explanation. Polishchuk went to court, writing in his statement: “I was fired on International Human Rights Day—such are our rights.” He won the case. He was then fired again “due to staff reductions,” with compensation for his forced absence. The chief of the Bila Tserkva police was very indignant that Polishchuk had “slandered” about Human Rights Day, banging his fist on the table: “In the Soviet Union, the rights of the working people are protected 365 days a year! But in the world of capital, where everything depends on the moneybag, there is only one human rights day.”

Around that time, Polishchuk bought a German “Praktica-L” camera, which could take close-up photos, and for Ivan HONCHAR’s ethnographic museum, he began re-photographing old pictures of people in traditional Ukrainian clothing. The KGB did not like this, and they set up a provocation. In the autumn of 1974, a stranger, a photographer, struck up a conversation with him in the “Melodiya” store. Polishchuk showed him his photos, and the man showed his. The photographer expressed doubt that Polishchuk could produce high-quality photographs and, “as a test,” slipped him a foreign calendar, from which Polishchuk made several color slides and one color print. In addition, the man brought Polishchuk two rolls of film and asked him to develop them. Polishchuk did not have time to develop them, so he did not know what was on them. He received a summons to appear in court on March 12, 1975, for a case concerning his reinstatement at work, but on the 11th, at 7 a.m., 5 people entered his apartment. The search lasted 3 hours.

Polishchuk was held in a pre-trial detention cell in Kyiv and then taken to the Lukyanivska investigative isolator. After the investigation was completed, Polishchuk submitted an application to the Kyiv Oblast Court requesting a public trial at the “Molodizhnyi” club at the construction site of the Bila Tserkva Tire Plant, where he had worked for seven years, in front of people who knew him. The case was heard from August 18–20, 1975, by the Judicial Collegium for Criminal Cases of the Kyiv Oblast Court, presided over by H.A. Dyshlya. The judge was very nervous, banging his fists on the table and breaking a piece of evidence—Polishchuk’s camera, which he could not open. The actual charge of producing pornographic images (Article 211 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR) was addressed by the court in the final minutes of the session: without any evidence or a single witness, the court “established” that the slides were produced “for the purpose of distribution.” The entire three days were spent investigating “deliberately false fabrications that defame the Soviet state and social system”—several conversations with acquaintances about the Soviet electoral system, national policy, Soviet democracy, and the leadership of the CPSU, often provoked by superiors and agitators between 1968 and 1974. Polishchuk defended himself quite successfully, arguing that what he had said was written in many books whose authors were at liberty. Judge Dyshel did not allow Polishchuk to get answers from witnesses to his questions: “Witness, the court withdraws the question. You do not have to answer. Give me your summons.” The charges also included the aforementioned letters to the editors of the newspapers “Visti z Ukrainy” and “Literaturna Ukraina,” which had been lying around for several years. Polishchuk refused the services of a lawyer. The court sentenced him to 3 years of imprisonment in a standard-regime corrective labor colony under Article 187-1 and 1 year under Article 211 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR, with confiscation of his photographic equipment. Although the trial was considered open, not even his mother and sister were allowed to attend. Polishchuk was shown the trial record only after 68 days (instead of the legal 3). He filed a 72-page cassation appeal, but it did not affect the Supreme Court's decision. On August 20, 1975, he submitted an application to the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, I.S. Hrushetskyi—it never left the investigative isolator.

While being transported in Dnipropetrovsk, Polishchuk was robbed by criminal inmates. He served his sentence in colony No. 2, a standard-regime colony in the city of Dzerzhynsk, Donetsk oblast. The entire colony administration gathered to see a live nationalist-anti-Soviet. The next day, he was put in a punishment cell for refusing to go to work. He came out covered in lice. He was saved by a bathhouse attendant—a Baptist named Ivan Melashchenko from Sloviansk.

The administration ignored Polishchuk's disability and forced him to do hard labor twisting spring mattresses. He was punished for not meeting the quota, although in reality his work was credited to criminal inmates. The authorities frequently summoned Polishchuk and tried to ruin his reputation, spreading rumors that he was an informer. He lived on the verge of starvation. He earned extra by drawing “marochky”—small handkerchiefs—for which prisoners paid him with food. When he was transferred to a drilling machine, Polishchuk met his quota and was able to buy 7 rubles' worth of food per month. But the foreman transferred him to another machine that lacked an automatic feed, requiring him to feed it by hand. Soon, three fingers on his right hand lost sensation and could not handle the load. Polishchuk was accused of malingering, but they eventually had to relieve him from work for a while. He exercised his fingers, and sensation returned. Incidentally, he was also offered an easy job: carrying the keys to the local zones for the authorities. Polishchuk publicly and categorically refused, which earned him a good reputation among the prisoners.

To spend less time in the crowded prisoner areas, Polishchuk enrolled in an evening vocational school to become a lathe operator. He achieved the fourth skill category. But he was transferred to assembling wooden crates, and on March 11, 1978, he was released. Before his release, he refused to be photographed in a suit and tie—he preferred to be pictured in his documents in his prison garb.

Polishchuk returned to Bila Tserkva. In the meantime, the “Bilotserkivkhimbud” trust had taken his apartment. All his property was gone. On March 28, Polishchuk went to see the chairman of the city council, Vasyl Zalevskyi. He allowed him to be registered in a dormitory and to get a job in the same trust, in the engineering preparation department for construction. In the “Myr” dormitory, they placed “stukachi” (informers) as his roommates. The section chief, Yaroslav Levchuk, feigning sympathy, questioned Polishchuk about his trial and imprisonment—and then wrote a denunciation to the KGB, stating that he had conducted educational work with Polishchuk, but Polishchuk had not yielded to his educational influence and in their conversation “made ideologically hostile statements.” After this, the informer was elected secretary of the trust's party committee, then appointed an instructor at the Bila Tserkva city committee, and an instructor at the Kyiv Oblast Committee of the CPU.

When Polishchuk got a job, he began to appeal to the authorities, claiming he had been illegally repressed. He was then summoned to the police and, in the presence of witnesses, placed under administrative supervision for six months, which required him not to leave the dormitory after 9 p.m., not to leave the city, and to check in at the police every Saturday. The formal reason: a character reference from the colony stating that Polishchuk had not been reformed. Polishchuk said: “You should have a problem with those who failed to reform me. I very much wanted to be reformed and asked our dear Soviet government what flaws I needed to get rid of and what qualities of a full-fledged citizen of a socialist, communist society I needed to acquire. But they did not answer that question, so I will not sign these conditions.” He did not violate the terms of the administrative supervision but warned that he would not go to the police to check in. Surprisingly, he was not punished for this.

He traveled with a letter about his illegal imprisonment to the village of Losiatyn to see Supreme Soviet Deputy Stepanyda Vyshtak, hoping she would pass it on to the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, O.V. Vatchenko. In Kyiv, at a theater on May 10, 1980, he handed a large, 37-page manuscript titled “A Petition” to a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR from his Bila Tserkva district, Dmytro Hnatiuk—it very quickly ended up with Prosecutor Bohachov, who later signed the warrant for Polishchuk's arrest. In the “Petition,” Polishchuk exposed the utter absurdity of the charges, cleverly using quotes from the works of Marx and Lenin, so that this talented piece reads like a biting feuilleton on “Soviet justice.”

On November 19, 1980, Polishchuk was arrested again, right at his workplace. His workspace and dormitory room were searched. During the investigation, he submitted four statements refusing a lawyer and insisted that the criminal case was unlawfully initiated. But in January 1981, he was sent for a psychiatric evaluation to the 13th department of the Pavlov Hospital. There he met fellow political prisoner Valeriy KRAVCHENKO. Fortunately, a medic from his hometown did not administer the prescribed 80 cc of sulfazin. The head of the 13th department, Tamara Mykhailivna Arseniuk, concluded that Polishchuk “exhibited signs of psychopathy with overvalued ideas of reformism,” but was sane. On April 10, 1981, the Kyiv Oblast Court, presided over by Judge M.M. Kyselevych, sentenced him to 3 years in a strict-regime camp for the “systematic dissemination, in oral and written form, of deliberately false fabrications that defame the Soviet state and social system” (Article 187-I of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR). This again involved several conversations with acquaintances about the electoral system, Russification, and the infringement of rights and freedoms, 4 letters to the editor of the newspaper “Radianska Ukraina,” and the “Petition” to Deputy D. Hnatiuk, in which he allegedly defamed the internal and external policies of the USSR and the “democratic achievements (!) of Soviet power.” This verdict, like the first, did not provide a single example of these “slanders.”

Polishchuk was very quickly transported to the village of Chornukhyne, Perevalskyi raion, Voroshylovhrad oblast. For the experienced prisoner, it was easier now. But they would not accept any of his complaints. A prisoner named Manko, who was being released on December 10, 1981, promised to take a letter from Polishchuk—an application to the Prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR about his illegal imprisonment. But he actually gave the letter to an orderly, who gave it to the deputy head of the regime. Polishchuk was thrown into a punishment cell “for attempting to illegally send correspondence,” and threatened with Article 62 (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”). He declared a protest hunger strike there, which he maintained for 25 days, the first 7 of which were dry. He lost his voice. When he drank water, he was able to speak. There were several people in the punishment cell, and they ate Polishchuk's ration. Someone informed Polishchuk's sister, Hanna Shapoval, about his hunger strike. The sister demanded an explanation from the administration. On January 4, 1982, Polishchuk was summoned by the colony chief, Ptashynskyi, who assured him that all his complaints would be sent to all state authorities. That day, Polishchuk ended his hunger strike.

The detachment chief, Pyokhov, refused to take him: “I don't need a corpse, get him out of here.” Polishchuk was placed in the medical unit. Its chief, Dniprov, saw that the prisoners had given Polishchuk a piece of bread with margarine and said, “Good, good, eat, eat.” Polishchuk also ate some pea soup—and almost died.

On the third day, he was already sent out to work. He couldn't work and lay on wood shavings. Two months later, he was given a broom—to sweep the work zone. Then he wove nets. He took courses for boiler operators.

On November 20, 1983, Polishchuk returned to Bila Tserkva, and on the 25th, he was issued a passport. A policeman, Lieutenant Nemov, was in charge of his employment. Polishchuk went to the police station every day and reported where he had been denied employment due to a lack of a residence permit. They would ask: “Where did you sleep last night? We'll register you there.” – “I slept on the electric train last night, so register me for the electric train.” The Bila Tserkva city executive committee, in the person of Vasyl Shevchenko, tried to push Polishchuk out of Bila Tserkva—sending him to Vasylkiv, Fastiv, Volodarka, Skvyra, but Polishchuk did not go there, because before his imprisonment he had a home and property in Bila Tserkva, which was lost due to the illegal actions of the authorities. He intended to appeal these actions. He took a temporary job as a boiler operator at the “Elektrokondensator” plant.

Polishchuk was registered in the “Ros” dormitory of the capacitor plant. He was moved from room to room many times, with “stukachi” (informers) placed as his roommates. Finally, they offered him a better room for three people. He refused. Then the deputy director of the plant for housing, Zhukov, summoned him and threatened: “Don't think you're going to dictate to us where you live and where you don't live—you'll live where we tell you, and with whom we tell you.” The department head Lohvynenko and the foreman Pivniuk lived there. Polishchuk immediately told them why he had been moved there and said he would not talk about himself so they would not be summoned to the KGB. That same evening, they left the room, and Polishchuk lived in it alone until his rehabilitation.

On March 9, 1984, Polishchuk and his friend Leonid Haponenko visited T. Shevchenko's grave in Kaniv, and on March 10, the KGB threatened him: “What you got wasn't enough for you, and you're still walking around chattering. You'll chatter your way into big trouble. We're drying crackers for your third term, no less than 12 years. And for now, the job of a stoker is too great a luxury for you.”

That same day, Polishchuk telephoned his former colleague—the chief project engineer, now secretary of the Bila Tserkva city party committee, Hennadiy Shulipa. He refused to see him. Instead, instructors from the city party committee yelled at him. Polishchuk stopped seeking rehabilitation.

While working as a stoker, Polishchuk refused to attend political information sessions: “I've heard enough of those informations to last until the final victory of communism, there's nothing for me to listen to there.” The foreman immediately reported it to the authorities. Polishchuk was transferred to be an auxiliary worker in the repair and construction department. He refused to participate in subbotniks or pay for DOSAAF stamps. They began giving him work that exceeded his physical abilities. He consulted doctors. A forewoman suggested he take an exam for a worker's skill category. This was allowed only after his third appeal to the Bila Tserkva prosecutor's office, and only for the third skill category, although he was actually performing work of the highest categories. Even in 1988, for not attending a meeting during working hours, he was punished with a 50% reduction in his bonus and threatened with dismissal.

In April 1989, the head of the investigative department of the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR, Volodymyr Prystaiko, informed Polishchuk that the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR had rehabilitated him in both cases due to the absence of a crime. The rehabilitation certificates were issued to him at his sister's request at the end of December 1989. He was awarded compensation of 10,080 rubles, but this money was lost to inflation. However, he was given an old, dilapidated dwelling, which he had to repair himself, breaking his leg in the process. He has been living in this apartment since February 1991.

Only after his rehabilitation did the department head offer Polishchuk a job as a foreman, but he refused. In June 1991, he retired.

In March 1989, Polishchuk, along with Leonid Haponenko, Mykola Pedchenko, Vasyl Marchenko, and others, created a chapter of the Ukrainian Language Society “Pochatok” (Beginning). They went to schools and institutions with their message, and held their founding conference in the “Lenin room” of the “Ros” dormitory, where Polishchuk lived. He gave a report, and M. Pedchenko was elected chairman. Polishchuk spent his entire vacation in November creating the TUM association and registering it. The TUM nominated Polishchuk as a candidate for the city council in the March 1990 elections, but he fell 42 votes short in the second round.

He has been a member of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons since 1989. That same year, the newspaper “Literaturna Ukraina” published his article about the 1933 famine.

In the early 1990s, Polishchuk participated in the creation of a community of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church in Bila Tserkva. When the UAOC split, he re-registered the community under the Kyiv Patriarchate of the UOC. On the day of the funeral of Patriarch Volodymyr (Vasyl ROMANIUK), he left Christianity.

Bibliography:

KHPG Archive: Interview with M. K. Polishchuk dated June 22, 2002.

M.K. Polishchuk's Archive: copies of the Kyiv Oblast Court verdicts of August 20, 1975, and April 10, 1981; Petition to the USSR Supreme Soviet Deputy for the Bila Tserkva electoral district, D.M. Hnatiuk, dated April 6–9, 1980.

Polishchuk, M. “Yakby my vchylys tak, yak treba…” [If We Studied as We Should…]. – Hromadska dumka (Bila Tserkva), 2006. – October 6.

Compiled on March 7, 2009, by Vasyl Ovsiyenko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Corrections by M. Polishchuk added on March 29, 2009.

Character count 21,078.

POLISHCHUK MYKOLA KINDRATOVYCH