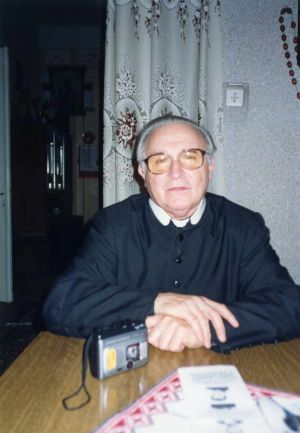

KAVATSIV, YOSAFAT (secular name Vasyl, son of Mykhailo and Varvara), born January 5, 1934, in the village of Yablunivka, Stryi Raion, Lviv Oblast – died June 4, 2010, in the city of Stryi, Lviv Oblast.)

A repressed Greek Catholic priest of the Basilian Order.

From a devout family with many children. His father was a worker, his mother a peasant. From a young age, the boy loved the church and wanted to dedicate himself to the monastic life of the Basilian Order and become a priest. He spent his free time in conversations with nuns and studied theology for 12 years with priests Dr. Maksymets and Father Dr. of Theology Tymchuk.

With the liquidation of the UGCC in 1946, the Kavatsiv family on his mother’s side stopped attending church and was entirely repressed. Vasyl attended secondary school. He did not join the Komsomol, and when his class was forcibly taken to the district committee, he escaped by jumping out of a second-story window. For this, his father was fired from his job as a mechanic at a distillery and transferred to work as a stoker.

After the 10th grade, Kavatsiv graduated from a financial and credit technical college (1952) and worked until 1957 at the Zhydachiv Paper and Cardboard Combine as an accountant in the settlement department.

In 1954, repressed priests began to return from imprisonment and exile. On December 22, 1954, Kavatsiv took monastic vows and became a monk of the Basilian Order. He diligently studied theological sciences. He collected food and money from Greek Catholics for parcels for the imprisoned Metropolitan Yosyf SLIPYJ, Father Shabak, Father Taras, and the Basilian Sister Servants.

In March 1957, Kavatsiv was arrested based on denunciations that he was maintaining contact with prisoners. On April 7, the Zhydachiv Raion Court sentenced him to three years of forced labor. He had to leave Zhydachiv within 24 hours. With difficulty, he found a job at a woodworking combine in Stryi, where he carried away scraps and sawdust from the workshop.

In 1960, Kavatsiv was hired as a stoker at Stryi school No. 10, then worked at school No. 2 as a manager and accountant for a meager salary of 35 rubles. He later worked as an accountant for the trade union of the teacher’s house in Stryi.

On May 24, 1962, Bishop Slyzyul, the Ordinary of Ivano-Frankivsk, laid his hands on Kavatsiv. He began to serve secretly. He held services in homes, at cemeteries, and near closed churches. Once in Lviv, at night, druzhynnyky (volunteer patrolmen) and police detained him and confiscated his service items. He moved to Lviv, but they would not register his residence, except in villages, and when they found out he was a priest, they would cancel his registration. This happened eight times. Eventually, believers bought a residence for the underground priests—it was confiscated. In matters of residence registration, Kavatsiv filed 24 complaints and traveled to Moscow seven times, but all in vain.

Kavatsiv began to open and consecrate closed and de-registered churches. The first such church was in the village of Lisnovychi, Horodok Raion (1970). The 700-year-old church in the village of Muzhylovychi in the Yavoriv region was falling into ruin. On Kavatsiv’s advice, the people restored it. After its consecration, on Christmas Eve 1980, he was detained, taken to Yavoriv, and interrogated all day about the church’s construction. When everyone had left, the head of the district executive committee, Ivanachenko, said: “Father Yosafat, I respect you immensely. What you have done will never be forgotten. And if I live to see better times (for it won’t always be like this), I will bring you to Muzhylovychi and carry you to the altar in my arms.” He did not act on the numerous denunciations against Kavatsiv (he later committed suicide).

In the village of Mshana, Horodok Raion, peasants restored a de-registered church built in 1700. On the parish feast day of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, December 4, 1977, the authorities ransacked it. Carved iconostases and icons were chopped with axes, carried out, and burned. People who tried to protect the sanctuary were set upon by dogs. The church was turned into a warehouse for television picture tubes. Kavatsiv, along with Father Roman Yesyp and the community, prayed outside the church in the rain and frost, without light. He knew the entire service by heart, so he could manage without books. On the Feast of the Presentation, December 4, 1979, the people broke the locks and carried the entire contents of the warehouse outside. A team of police and civilians arrived from the district. Kavatsiv finished the Divine Liturgy and left the church in a tight circle of men and women, who also carried out all the church items.

The work was dangerous; he slept only on buses. In total, Kavatsiv worked in 78 villages and cities in Galicia, in Kyiv, in Lithuania, and in Kazakhstan, working at night while having to be at an official job during the day (as a stoker, in a hospital) to avoid being imprisoned as a “parasite.” When he traveled far, he had to pay people to substitute for him.

With his own knowledge and funds, Kavatsiv prepared 31 priests for the altar. With his participation, 6,000 signatures were collected on a petition for the legalization of the UGCC, which was sent to the 26th Congress of the CPSU in 1976.

In 1977, Kavatsiv participated in the transfer of the relics of Bishop Yosafat Kotsylovsky from Kyiv to Lviv. This became one of the reasons for his arrest on March 17, 1981. At that time, the commissioner for religious and cult affairs of the oblast summoned him and demanded that he sign a renunciation of performing services. Kavatsiv wrote that, in accordance with Article 124 of the Constitution, he had the right to serve. As soon as he arrived at his sick mother’s home in the village of Yabluniv, 12 men burst in with a search warrant. They confiscated all church items, and Kavatsiv, along with Father Roman Yesyp (born October 11, 1951), who lived there, was taken to the KGB on 1 Myru Street.

Kavatsiv spent 10 days in a basement with rats, after which investigator Mykhailo Vasyliovych Osmak charged him under Article 138 Part 2 of the Ukrainian SSR Criminal Code (“Violation of the law on the separation of church from state and school from church”) and Article 209 Part 1 (“Encroachment on the person and rights of citizens under the pretext of performing religious rites or other pretexts”). The investigation lasted eight months. In his cell, he suffered from lack of air and water, from filth, and from the lawlessness of common criminals. In the first few weeks, Kavatsiv’s hair turned gray, but he did not sign a single protocol of the six-volume case file. The investigator collected testimonies from children in villages, written under dictation, stating that the priest forbade them from eating meat, watching television, and dancing (referring to Christian behavior during Lent).

The Lviv Regional Court heard the case of priests Yosafat Kavatsiv and Roman Yesyp from October 14 to 28, 1981, in the builders’ club on Stefanyka Street in the presence of a “special public” and journalists. Crowds of believers gathered near the building, protesting the trial. Many “witnesses,” including children, recanted their ascribed testimonies, saying that the priest had not spoken against the authorities. The sentence was 5 years of imprisonment in general-regime camps and 3 years of exile with confiscation of all property. Priest Roman Yesyp, born October 11, 1951, received the same sentence. The verdict stated that “Kavatsiv and Yesyp conducted services both day and night, on weekends and on workdays, in non-functioning, de-registered, and active Orthodox churches, near them, as well as in cemeteries and in the homes of individual believers, involving many citizens, including children, thereby violating public order... Many citizens gathered, sometimes over 300 people... Kavatsiv and Yesyp, using so-called confessions, organized and conducted the teaching of religious dogmas to children, forced them to learn certain prayers, observe fasts, not to visit clubs, not to participate in cultural and mass events, that is, they carried out activities involving encroachment on their rights and health.”

On December 15, 1981, Kavatsiv’s cassation appeal was heard by the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR. It only changed the motivation for the priests’ actions, removing the charge of “mercenary motives,” which was considered an aggravating circumstance. The press and radio at the time spoke and wrote a great deal about the “followers of Sheptytsky, Slipyj, Bandera, and Stetsko.” Kavatsiv’s father, seeing the trial of his son on television, said goodbye to him and died on December 13, 1981.

After Christmas, on January 8, 1982, Kavatsiv was taken for transport. He was struck by the lice-infested Poltava transit prison, where common criminals reigned with impunity.

Kavatsiv served his sentence in the experimental camp No. 319/7 in the village of Perekhrestivka near Romny in the Sumy Oblast. He had high blood pressure (265/165) and spent five weeks in the medical unit. He then worked as an accountant, calculating prisoners’ wages, but soon, by order of the KGB, he, a disabled person of the II group, was assigned to hard labor.

The zone was divided into “local zones.” Conditions in the barrack for 750 prisoners were harsh: overcrowding, lack of water, dirt, lice, rats, soggy bread, poor-quality and monotonous food (the cost of the daily ration was 18.5 kopecks), humiliating searches, compulsory physical exercise, military training, political classes, movies in a windowless hall where people fainted, 18 checks a day, and most vexing for a priest—the vulgar profanity of prisoners and guards. Only one camp chief, Kyrylenko, spoke without swearing.

KGB officers repeatedly visited Kavatsiv, offering him a transfer to Russian Orthodoxy, promising his release and appointment as a bishop at St. George's Cathedral. Kavatsiv was summoned before the supervisory commission eight times, but since he did not admit his guilt, they did not submit his case to the court for early release.

In March 1986, Kavatsiv was taken for transport to be sent into exile in Uralsk, but in the Sumy transit prison, he was detained for a long time and then released from exile as a disabled person of the II group. They returned his passport and gave him 30 rubles for the road.

Kavatsiv’s mother was on her deathbed but recognized her son. She died two weeks later. Her son, holding back tears, buried his mother as a priest.

For eight months, he did not take up official work, so he was warned of criminal liability for “parasitism.” He got a job as a cloakroom attendant at a medical institute, but soon was hospitalized for 4.5 months with hypertension. He spent another 3.5 months at home. He was granted II group disability status.

Having recovered somewhat, he began to serve in the Annunciation Church in Stryi, alternating with a Russian Orthodox priest. Conflicts arose between the faithful of the UGCC and provocateurs who masqueraded as Orthodox. Eventually, Bishop Starniuk appointed Kavatsiv as rector of the church, and he, together with the People's Movement of Ukraine (Rukh), “Memorial,” and other democratic organizations, did not allow the Orthodox priest into the church.

On Father Yosafat’s initiative, a cross was erected at an intersection in Stryi, and a mound was raised for the Sich Riflemen. He defended a monastery for the Sister Servants. He ordained 15 priests, married people who had lived for decades without a church wedding, and people confessed for the first time in 30–40 years.

Bibliography:

Autobiographical sketch by Father Yosafat Kavatsiv (typescript, before 2000). https://museum.khpg.org/1203888925

KHPG Archive: Interview with Father Yosafat Kavatsiv in Stryi, February 3, 2000. https://museum.khpg.org/1203670497

Mizhnarodnyi biohrafichnyi slovnyk dysydentiv krain Tsentralnoi ta Skhidnoi Yevropy y kolyshnoho SRSR. T. 1. Ukraina. Chastyna 1. [International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in the Countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the former USSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1.]. Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny,” 2006. – pp. 259–263. https://museum.khpg.org/1128060331

Rukh oporu v Ukraini: 1960–1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk [The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960–1990. An Encyclopedic Guide] / Foreword by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010. – pp. 271–163; 2nd ed.: 2012. – p. 300.

Vasyl Ovsiyenko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Corrected by Father Yosafat on June 13, 2004. Final reading on August 8, 2016.