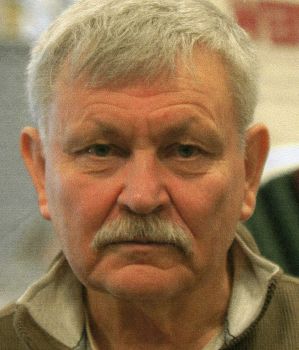

Composer, musician, participant in the Ukrainian human rights movement. Political prisoner (1978-81).

His mother (1916–1990) was from the village of Matusiv, Cherkasy Oblast, and his father (1911–1975) was from the village of Trytelnyky, Khmelnytskyi Oblast; they married in Odesa. His father was taken as a Romanian prisoner of war, and his mother and son had to move during the war to the town of Zhmerynka in the Vinnytsia region, to his father's relatives. His childhood was spent there. His father returned from captivity and constantly expected to be arrested. His mother used to say of the Bolshevik government: “Since the earth has existed, there has been no greater slavery on earth than communism.” A natural Ukrainian atmosphere reigned in the family. From childhood, Vadym knew almost the entire “Kobzar” by heart. But he was drawn to music, which in Zhmerynka could only be heard on the radio. For a downy shawl, his mother bought him an accordion at the market, which he learned to play on his own.

From 1945–1955, Vadym attended school. He was good at mathematics but enrolled in the Reinhold Glière Kyiv Music College, from which he graduated in 1959. That same year, he entered the Kyiv Conservatory. In his 4th year, he came to a national consciousness through music: for a people to have a full-fledged musical education, a national state was needed. And he began to build the state starting with himself: first and foremost, he returned to his native language. He had a conversation about this with a KGB officer, who warned him against nationalism. To which S. replied: “I am of Cossack lineage, so I have no great fear of you. Especially since I am not doing anything anti-state. I will speak Ukrainian and I will write Ukrainian music.”

He led an orchestra in the “Poltava” restaurant. He was being considered for the position of director of the Ukrainian Chamber Pop Orchestra. But KGB agents intervened. S. went to the Ukrainian Choral Society to find out who controlled the arts in our country: the KGB or arts organizations? The result: S. became unemployed.

Until then, S.'s songs had been recorded for the radio. He wrote the music for a film about Nina Matviienko, “Rusalchyn tyzhden” (Mermaid Week), which features a song in his arrangement, “Chervona Kalynonka” (Red Viburnum). Later, a record with this song was released without his name. The same happened with the song “Rode miy krasnyi” (My Beautiful Kin).

In 1963, along with artist Alla HORSKA and poet V. SYMONENKO, S. organized a tour of the “Zhayvoronok” (Skylark) choir of Kyiv University, which was popular among students, through villages to Kaniv. An “academic failure” was arranged for him, and he was expelled from the conservatory. To avoid further persecution, he went to Volyn, where he directed a choir in a collective farm for a year and a half. Then he returned to Kyiv and taught music in schools. But he did not stay anywhere for long: he was fired for communicating with dissidents, for behaving like a Ukrainian.

He married a teacher, Halyna Ripa (1937-1985), and their son, Volodymyr, was born in 1969.

Countless times, S. was summoned for questioning about I. SVITLYCHNY and other arrested members of the Sixtiers movement, and was pressured to give testimony against them. And a “repentant” article was published in the newspaper *Shlyakh Komunizmu* (The Path of Communism), but there was not a single word about the influence of I. SVITLYCHNY or other dissidents on S. S. refused to do so. He also refused to make similar accusations against anyone on television. The terror intensified: he could not find work anywhere, could not earn a single kopeck. This went on for years. It caused tension in his family.

Since there were no facts for which S. could be arrested on political grounds, provocations were staged to fabricate a criminal case. S. understood this and avoided dangerous situations.

Finally, in August 1977, S. submitted an application to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, requesting permission to emigrate to Canada to complete his musical education. In it, he wrote something like this: “I am not in the military; I do not know any state secrets. I am a musician and I want to pursue music. You have a beautiful country, but please let me out of it.” He took this application to Moscow and submitted it at the Kremlin's reception office. The result was not long in coming.

On the evening of December 13, 1977, on Franko Street, where S. lived, a man fell at his feet, jumped up, and shouted: “What did you hit me for?” A police car was waiting nearby, and 8 witnesses were found (only one of them a civilian). S. was knocked to the ground, grabbed by his arms and legs, thrown into the car, and taken for a forensic medical examination. No alcohol was found in his blood. Then, in the middle of the night, they took him for another examination. S. demanded that the blood test be done in his presence, but he was brutally pushed out and taken to a pre-trial detention cell. On the third day, he was charged with hooliganism and thrown into the Lukyanivka pre-trial detention center. In his cell, instructed criminal inmates offered S. drugs and tried to beat him, but S. bravely defended himself.

Considering himself not guilty, S. declared a hunger strike, which he maintained for 29 days (according to another source, 53 days, until the trial). He was force-fed through a tube. He refused the services of a lawyer who approached him before the trial began on February 3, 1978. Despite the fact that the “victim,” Shcherban, and the “witnesses” gave contradictory testimonies, the Radyansky People's Court of Kyiv sentenced him under Article 206, Part 2 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR (“hooliganism, with infliction of minor bodily injuries, without impairment of health”) to 3 years of imprisonment in general-regime camps. Only S.'s mother and uncle were present at the trial; friends and acquaintances were brutally pushed out of the courtroom.

On February 10 of that year, Nadiya SVITLYCHNA and Mykola HORBAL sent a letter to the Prime Minister of Canada, Pierre Trudeau, in defense of S. On March 22, 1978, the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR, under the chairmanship of Deputy Chairman P.H. Tsuprenko, considered S.'s cassation appeal and left the verdict unchanged, adding that S. had struck the victim twice.

S. served his sentence in general-regime penal colony YuZ-17/7 in the village of Stara Zburyivka, Holoprystan Raion, Kherson Oblast. It was a zone of lawlessness. He had to physically defend himself. Officers spoke with him dozens of times, trying to get him to admit his guilt, promising early conditional release, but S. stood his ground: “I did not hit him.” They flew his wife in to persuade him to admit guilt.

He was assigned to a construction brigade where he had to carry heavy loads. They tried to set him up for a new case by staging a fight and organized all sorts of provocations. They moved him from one detachment to another, “lost” his account, did not credit his wages—and he could not buy additional food. So S. went on strike. The result: 10 days in a cold punishment cell. It was impossible to sleep there. He endured by constantly moving. When he came out of the punishment cell, the prisoners greeted him as a victor: they laid a white embroidered towel at his feet. The chief took him to the food stall because his account had been “found.”

He had a cerebral hemorrhage in the zone. He saved himself with physical exercise.

Before his release, S. hid excerpts from his case file in the heel of his shoe and smuggled them out on December 13, 1980. He was under administrative surveillance for 6 months.

The search for work began again. The blackmail continued for 9 years. Finally, S. pointed to an axe and told Major Chypak: “I’ve served three years. What more do you want from me? I want to write songs. And if you come to arrest me for my songs again, I’ll kill as many of you as I can.”

His mother said: “You came out of captivity a hundred times angrier. Go abroad, because there will be no life for you here.” He managed to do so on January 7, 1990. In Canada, former political prisoner Yosyp TERELYA helped him. Disappointed with the Ukrainian intelligentsia there, he moved to the USA. He wrote music, but was only able to publish it occasionally. After 15 years, he became convinced that it was pointless for a Ukrainian artist to live outside of Ukraine, and in 2005 he returned home. In Zhmerynka, he repaired the house where he lives to this day. He retains his US citizenship.

His son Volodymyr graduated from a university in the USA but has taken Ukrainian citizenship.

S.’s criminal case, No. 11-866, was destroyed after its retention period (15 years) expired, so the judicial authorities refuse to review it. But S. has kept copies of some documents and is demanding a review of the case and his rehabilitation.

Bibliography:

Chornovil, V. Works: In 10 vols. Vol. 3. (“Ukrainskyi Visnyk,” 1970–72). Compiled by Valentyna Chornovil. Foreword by M. Kosiv. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2006, pp. 563-564. (Ukrainskyi Visnyk, no. 4, January 1971).

Herald of Repression in Ukraine. The Foreign Representation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. Edited and compiled by Nadiya Svitlychna. New York. 1981, no. 2-258, 3-98, 5-70; 1982, no. 2-34.

The Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: Documents and Materials. In 4 volumes. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Kharkiv: Folio, 2001. Vol. 3. Documents and Materials. August 1977–December 10, 1978. Compiled by V. V. Ovsiyenko. pp. 90-91, 117, 211 (Information Bulletins of the UHG No. 1, 2, 4).

Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group Interview from November 11, 2008.

The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960–1990. An Encyclopedic Guide. Foreword by Osyp Zinkevych and Oles Obertas. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010, p. 605.

SMOHYTEL VADYM VOLODYMYROVYCH