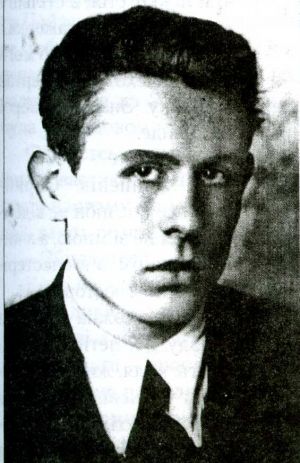

VYACHESLAV IVANOVYCH PROKOFYEV (October 28 [according to his documents, October 31], 1928, Pyriatyn, Poltava Oblast – June 1, 2009, Kyiv)

A history student who was repressed on trumped-up charges.

The Russian surname was brought by his great-grandfather, Andriy, from the tsarist army. In 1929, the family moved to Kyiv. In 1936, Vyacheslav started at School No. 16 and had completed five grades before the war. He survived the occupation and, as he wrote in his questionnaires, “was not employed anywhere and was not engaged in any activity.”

After the liberation of Kyiv, he studied at a music school in 1945–46 and at School No. 93. For the 9th grade, he attended the prestigious School No. 92. He graduated in 1948 and passed the entrance exams for the History Faculty of the Taras Shevchenko Kyiv State University, but he did not get in due to competition. He was admitted in 1949.

On June 1, 1950, he was unexpectedly arrested by the MGB and charged with fabricated accusations of “preparing for an armed uprising” (Article 16-54-2 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR—point 16 indicating he *could have* committed this crime), “possessing anti-Soviet literature” (Article 54-10, part 11—he had pre-revolutionary editions of S. Rudansky, M. Hrushevsky, and the *Notes of the T. Shevchenko Scientific Society* from 1923–1927), and “participating in an anti-Soviet organization” (Article 54-11). The investigation was based on the testimony of Leonid Lyubetsky (b. 1927), a third-year student arrested on April 12, 1950, who passed himself off as the leader of an anti-Soviet organization called the “People's Liberation Party” (Narodno-osvoboditelnaya partiya). This organization had allegedly been formed on the night of July 15–16, 1948, and supposedly held two more “gatherings.” During a search of Lyubetsky's residence, a “Program-Manifesto” and “Theses for a Report at the First Congress” were found. The organization's purported goal was to overthrow the Soviet government through an armed uprising. In connection with this case, 32 people were interrogated, and 17 were charged: young men and women born between 1925 and 1930, all students, 13 of whom were Komsomol members.

The fact that this case was fabricated against nationally conscious Ukrainian youth is evidenced by the fact that Lyubetsky—an unstable, morbidly self-centered individual with tendencies toward Russian chauvinism and anti-Semitism—had long been telling many acquaintances and strangers that he headed an anti-Soviet organization. The MGB had operational intelligence about this.

Without his knowledge, P. had been expelled from the university by the rector's order on May 24, 1950, a week before the arrest warrant was signed (May 31).

He was subjected to 11 interrogations, 6 of which took place at night. He denied any involvement in the organization, but the investigator, Kuznetsov, deprived him of sleep for an extended period, and he eventually signed the interrogation protocol. “You signed it—that means you confessed,” the investigator stated. The same was done with the other accused.

On July 26, 1950, P. signed the document under Article 200 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, signifying the end of the investigation. On July 31, 1950, the case was transferred to the Special Council (OSO) of the USSR Minister of State Security. There was no trial. P. was moved from the pretrial detention center at 33 Korolenko Street to Lukyanivska Prison, where he was informed of the OSO’s decision to sentence him to 10 years of imprisonment. L. K. Lyubetsky received 25 years, ten people received 10 years each in special-regime camps (including the future writer Mykola Hlukhenky), and 5 people received 8 years each (including the future artist Volodymyr Kutkin).

Before being sent to the camps, P. had a visit with his mother. At the end of September 1950, he was transported to Vorkuta. He served his sentence in special-regime camps No. 4 and No. 40. He worked in a mine, initially as a carpenter in a ventilation brigade, and later as a gas meter reader. He behaved with dignity. He did not file a petition for a pardon, as that would have meant admitting his guilt. His father petitioned on his behalf and received a rejection from the chancellery of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on October 28, 1953. P. participated in a strike demanding a relaxation of the detention regime. In the same year, his guard escort was removed. In the summer of 1954, his mother came for a visit.

The Central Commission for the Review of Cases reviewed the Lyubetsky group's case on November 22, 1954. It reduced his sentence to 10 years, rehabilitated thirteen individuals, and amnestied three. P. never saw this commission—he was unexpectedly released on January 11, 1955, with all charges dropped and fully rehabilitated under Article 204-b of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (case dismissed due to the absence of a crime).

He returned to Kyiv. He persistently sought reinstatement in the correspondence division of the History Faculty at the university. He graduated in 1960. In the meantime, he worked as a salesman in bookstores and as a music and singing teacher in schools. He noticed he was under surveillance and avoided several provocations. In 1959, he married Inna Berezenko, who was not afraid of his past. They lived in harmony for 39 years and raised a son, Ivan.

P. passed his candidate's minimum exams and, in 1964, became a lecturer in the History Faculty of Kyiv State University. In 1972, he defended his candidate's dissertation, and from 1984, he was an associate professor in the Department of the History of Foreign Socialist Countries. He authored over 50 printed pages of scholarly works and publications. He was awarded the medals “Veteran of Labor” and “In Commemoration of the 1500th Anniversary of Kyiv.” He retired in 1989.

P. wrote candidly: “I was not inclined toward political activity. The Sixtiers movement passed me by.” Since 1989, he was a member of the Kyiv Society of Political Prisoners and Victims of Repression. His autobiographical books are a serious historical study and valuable living testimony about the 1930s and 1940s, and about the Vorkuta camps. He also compiled biographical notes on his co-defendants.

Bibliography:

1.

*Taka dolya moya (Spohady kolyshnoho politychnoho v’iaznia)* [Such Is My Fate (Memoirs of a Former Political Prisoner)]. [No publishing data] Kyiv, 2000, 106 pp.

*“Taka dolya moya…” (Spohady kolyshnoho politychnoho v’iaznia)* [“Such Is My Fate…” (Memoirs of a Former Political Prisoner)]. [No publishing data] Kyiv, 2002, 200 pp.

*Vy zaareshtovani. Zdayte zbroyu (Spohady i notatky kolyshnoho politv’iaznia)* [You Are Under Arrest. Surrender Your Weapons (Memoirs and Notes of a Former Political Prisoner)]. [No publishing data] Kyiv, 2006, 344 pp.

2.

Filippova, Inna. “Fate and Choice.” *Narodna Hazeta*, no. 19 (573), 2003. [A review of the book: Vyacheslav Prokofyev. “Such Is My Fate…”]

Filippova, Inna. “From the Angle of a Certain June Date.” *Narodna Hazeta*, no. 23 (869), 2009.