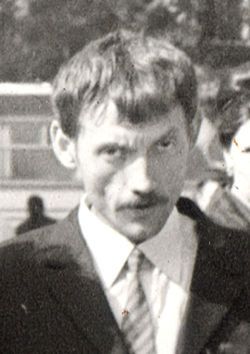

From the Sixtiers generation. A worker, poet, renowned philatelist, and member of the resistance movement.

He was born in a Ukrainian colony in the Volga region. At the age of two, his parents, Mykola (b. 1913) and Tetyana (b. 1917), brought the child to his grandparents, Yerema and Khivrya Mohylny, who lived in the Chokolivka neighborhood of Kyiv. During the era of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, this grandfather had been a volost (district) commissar. They survived the German occupation and the Soviet bombing of May 13, 1943. Viktor’s father and mother perished in the war. An inquisitive boy, he communicated with recent villagers who had settled in Chokolivka to escape collectivization and famine, as well as with guards from the prisoner-of-war camp. He was born with a heightened sense of justice, which led to conflicts with his teachers. He wrote his first poem in the third grade.

In 1952, he completed seven years of schooling and enrolled in a polytechnic school for communications, where instruction was conducted in Russian. In his second year, he published a wall newspaper—in Ukrainian. Beginning in 1956, he was assigned to work as a telegraph technician in Uzhhorod, and later in Chop. He married Aurélia (Oronka, Yaryna) of the Kuchmash family, a Hungarian woman who became Viktor's faithful companion (she passed away in 1997). In 1960, their daughter Dzvinka was born, and on September 16, 1963, their son Attila was born, who later became a renowned poet (d. September 3, 2008).

From the autumn of 1957, he was a technician at the Kyiv Central Telegraph. He later worked at the Paton Institute of Electric Welding in the electrothermics laboratory. Because he spoke Ukrainian with everyone in Kyiv, he had countless conflicts on this basis. He wrote poetry and, for the sake of intellectual fellowship, attended meetings of various literary studios, including the one at the “Molod” publishing house, which was headed by Dmytro Bilous. After the Party's criticism of Stalin’s personality cult, he decided to seek the truth for himself: he enrolled in the history faculty of the University of Marxism-Leninism. He lasted only one academic year (1960–1961), as he became convinced that communist ideology was fraudulent. At the entrance exam for Ukrainian literature at the Taras Shevchenko Kyiv State University in 1962, M. sincerely interpreted the image of Shevchenko’s Kateryna as a metaphor for Ukraine, ruined by a “Moskal” (a derogatory term for a Russian). As a result, he was not accepted.

His poems were published in the journals *Dnipro* (no. 4, 1961, and no. 10, 1962) and *Vitchyzna* (no. 10, 1962). Starting in 1963, the “Molod” publishing house was preparing a book of his poems, *Zhovta vulytsia* [Yellow Street]. In 1961, the head of the poetry department at the “Dnipro” publishing house, Anatoliy Kosmatenko, recommended M. for the first seminar-conference of young authors in Odesa. There, he met many young creative individuals, including Anatol Shevchuk and Mykola Vinhranovsky.

Gradually, the Mohylny home became a center of Ukrainian cultural life that attracted many soon-to-be-famous writers, artists, and public figures. Among those who visited were Mykola Plakhotniuk, Yuriy Murashov, Vitaliy Shevchenko, the brothers Anatoliy and Valeriy Shevchuk, Mykola Kholodny, and Yuriy Koval from Lviv. “When I came to Kyiv from the village to study, I felt that a Ukrainian was a stranger in the capital of Ukraine, that he was demeaned here. It was only when I found myself on that island of independence, where the Mohylny family lived, that I felt: this is the ground where you can land, where you can be yourself and grow,” says Oles Shevchenko. Younger visitors called M. their spiritual father. The walls of the apartment were covered with witty slogans, poems, and drawings. Here, one could find rare literature to read, such as Ivan Koshelivets’s *Contemporary Literature in the Ukrainian SSR*, and later, *samizdat*. In effect, it operated as an informal literary club. During these gatherings, his wife would stand guard around the house to prevent anyone from approaching and eavesdropping.

In the summer of 1963, M., along with the poet Hryts Tomenko and the artist Lyuba Panchenko, organized a studio for worker-poets called “Brama” (Gateway) at the Zhovtnevy Palace of Culture (where the Creative Youth Club was also located).

On March 24, 1965, the “Siaivo” (Radiance) literary studio (led by Anatoliy Yakovych Helman) was scheduled to hold an evening in memory of T. Shevchenko at the Gorky Machine Tool Plant club. But the doors were not opened for them. The event took place, surrounded by police and "druzhynnyky" (volunteer patrolmen) with blue-and-red armbands, in the Park of the 21st Party Congress, in the Nyvky neighborhood, where M. managed the reading pavilion. Vasyl Stus hosted the evening. M. also read his poem “Fragment,” which features a “sawn-off shotgun” and “blue-eyed Moskalkas” (female ‘Moskals’), and the poem “The Wind,” where “in a city without a storm, flags are suffocating.”

The following Saturday, the district party committee held a meeting about this event, and on Sunday, the city committee met. M. was summoned to the director of the Institute of Electric Welding, but he refused to go. He was protected from dismissal by Oleksiy Bulyha, also a poet and head of the electrothermics laboratory, who convinced the director that M. was indispensable to the institute as a skilled specialist. However, in February 1966, after Bulyha’s death, he was “downsized,” and another person was hired in his place the very next day.

On October 1, 1965, the newspaper *Literaturna Ukraina* published M.’s article “The Trouble with Consonants” (about the banned letter Ґ). In 1968, he was supported by Borys Antonenko-Davydovych with the article “The Letter We Miss.” Together with Oles Shevchenko and Hryts Tomenko, M. visited him.

In early 1967, M.’s poems were included in the almanac *Vitryla* (Sails). That same year, on September 30, the newspaper *Nove zhyttia* (New Life) in Czechoslovakia published M.’s article “We Must Reach an Understanding,” which touched upon the topic of repressions against writers in the 1920s and 1930s.

On the evening of May 22, 1967, M. came to the T. Shevchenko monument. Although he did not speak or show any particular activity, he was among four people (Ihor Duhov, Volodymyr Kolyada, Leon Rothstein, and M.) who were seized and taken by bus to a police station on T. Shevchenko Boulevard. Several hundred participants of the gathering, at the call of Mykola Plakhotniuk, marched to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, demanding their release. On Khreshchatyk Street, they were doused with water from fire hoses. At half past one in the morning, the Minister of Internal Affairs, Ivan Holovchenko, himself, along with the deputy head of the KGB, Kalash, came out to the people wearing a vyshyvanka (embroidered shirt) and said, “The boys got a little hot-headed. Disperse, and the detainees will be released.” However, the demonstrators did not disperse but waited until they were released at three in the morning at Kalinin Square (now Maidan Nezalezhnosti). Later, at a meeting between Holovchenko and workers of the “Lenkuznia” factory, M. sent him an unsigned note about the groundless detention. A few months later, the KGB agents “identified” him and summoned him for a conversation. He was forced to write an explanation. Subsequently, M., an electrician and electrical fitter, was sent on business trips far from Ukraine—to Vyborg, Tashkent—on Shevchenko days.

The publishing house returned the manuscript of his poetry collection to him. He went to argue his case with Tamara Hlavak, the secretary of the Central Committee of the Komsomol for ideological matters. She detected “pagan motifs” in his poems and advised him to write a few “ideologically sound verses,” after which the collection would be published. Not a single book of M.'s was published during the Soviet era.

Having learned that Vsevolod Hantsov—the sole survivor of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (SVU) case—was living in Chernihiv, M. wrote him a letter with a purely scholarly question about sibilant consonants. This was a great support for Hantsov, who soon replied with a detailed letter.

After the arrests of the Ukrainian intelligentsia in January 1972, M. was repeatedly summoned to the KGB for interrogation in the case of Mykola Kholodny. They hinted that Kholodny was testifying against him, but M. confirmed nothing. These summonses, threats, and harassment are described in M.’s poem “My Life” (“I was frightened,” 1978).

Shortly after the arrest of UHG chairman Mykola Rudenko (February 5, 1977), M., along with Oles Shevchenko, went to see Oksana Meshko. Without her knowledge, on his own initiative, he translated the UHG’s Declaration and its Memorandum No. 1 into Russian, typed them on his own typewriter, and O. Shevchenko took these documents to Moscow to Zinaida Hryhorenko, the wife of UHG member General Petro Hryhorenko. Very quickly, they were broadcast on the Russian-language service of Radio Liberty.

On March 31, 1980, Stepan Khmara, Oles Shevchenko, and Vitaliy Shevchenko, who had published issues no. 7–8 of *The Ukrainian Herald* in 1974, were arrested. On the same day, investigators detained M. at his workplace, took him home, and, with the sanction of the Lviv Oblast prosecutor, conducted a search, during which they seized 34 items, including documents, books, notebooks, and a “Moskva” typewriter. Among them were a diary, letters, a typescript of Valentyn Moroz’s article “Amid the Snows,” an undelivered speech by Mykola Kholodny, and Ivan Bilyk’s book *The Sword of Ares*. By an investigator's order dated September 15, 1980, these items were added to the case as material evidence. M. was summoned for interrogations on April 21 and 22, May 22, and August 8, 1980. They tried to make him a witness in this case, but M. did not provide the required testimony. Moreover, at the trial in Lviv in December, M. demonstratively “did not understand” the judge, forcing him to switch to Ukrainian. He proposed to analyze every line of his poem “My Life,” which had been seized from O. Shevchenko, and promised to prove that it contained no slander against the Soviet reality. To prevent M. from being accused of disseminating anti-Soviet literature, the defendant Shevchenko claimed that he had taken the poem from a table in M.'s home without the author’s knowledge, essentially stealing it. The investigation did not officially raise the issue of the translation of UHG documents—it was an embarrassment before Moscow that they had missed M. and O. Shevchenko in 1977.

On one occasion, M. was detained on the street by police officers and taken to their station, allegedly on suspicion of theft. They apologized and released him. During this time, a listening device was installed in his home.

On February 21, 1981, M. was “prophylactically treated” by the 5th Directorate of the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR for “nationalist statements and the creation of poems with ideologically harmful content.” He was issued an official warning in accordance with the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of December 25, 1972.

At M.’s request, filed in 1998, the SBU returned none of the seized items and provided no response regarding the listening devices. According to a document dated December 25, 1990, the materials concerning M. were destroyed due to the expiration of archival storage periods, in accordance with KGB order of the UkrSSR No. 00185 of December 10, 1979, and KGB USSR directive No. 5s-1988.

During the era of “perestroika,” M. became co-chairman of the strike committee at the “Lenkuznia” factory, where he had worked for 25 years, until 1991.

Under the pseudonym Vit Vitko, he published two small books of children's poems, written for his grandson: *Ravlyk-Muravlyk* [The Snail-Ant] (1988) and *Hoida raz, hoida dva* [Swing Once, Swing Twice] (1989). M.’s poems were included in the publication: *The Eighties: An Anthology of New Ukrainian Poetry*, compiled by Ihor Rymaruk, Edmonton, 1990; and in the anthology *Svit "Veselky"* [The World of "Veselka"] (2005). M.'s reflections on his life experience were expressed in the book *Csokolivka, csokolj meg!, abo Nadkushene yabluko: Khymeryky* [Chokolivka, Kiss Me!, or The Bitten Apple: Chimerics] — Stolitsya, 1999, 43 pp., published under the pseudonym Vykhtir Orklyn. The poet used the genre of the British limerick, created by Edward Lear—a short verse where the same word is repeated in the first and the last (fifth) line.

On November 21, 1999, a creative evening for M., hosted by M. Plakhotniuk, was held at the Sixtiers Museum.

M. is a world-renowned philatelist. He collects, among other things, letters from places of detention. Together with Vyacheslav Anholenkom, he has been publishing the *Ukrainian Philatelic Herald* since 1989.

He lives in Kyiv.

Bibliography:

1.

Mohylny, Viktor. “The Trouble with Consonants.” *Literaturna Ukraina*, October 1, 1965.

Mohylny, Viktor. “We Must Reach an Understanding.” *Nove zhyttia*, September 30, 1967. (Czechoslovakia).

Vitko, Vit. *Ravlyk-Muravlyk* [The Snail-Ant]. Kyiv, 1988.

Vitko, Vit. *Hoida raz, hoida dva* [Swing Once, Swing Twice]. Kyiv, 1989.

Orklyn, Vykhtir. *Csokolivka, csokolj meg!, abo Nadkushene yabluko: Khymeryky* [Chokolivka, Kiss Me!, or The Bitten Apple: Chimerics]. Stolitsya, 1999, 43 pp.

Orklyn, Vykhtir. “Khymeryky” [Chimerics]. *Holos Ukrainy*, no. 172 (2174), September 17, 1999. (Foreword by Vitaliy Zhezheria, “The Brave Chaffinch of the Lord God”).

Mohylny, Viktor. “The Story of One Poem.” *Chas* newspaper, January 29–February 4, 1998.

V. Mohylny’s website: http://www.orklyn.narod.ru/

2.

Chornovil, V. *Works: In 10 Volumes*, vol. 3 (*The Ukrainian Herald*, 1970–72). Compiled by Valentyna Chornovil. Preface by M. Kosiv. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2006, pp. 203–204; p. 886; Vol. 4, bk. 1. *Letters*. Compiled by M. Kotsyubynska, V. Chornovil. Preface by M. Kotsyubynska. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2005, p. 517; Vol. 4, bk. 2. *Letters*. Compiled by M. Kotsyubynska, V. Chornovil. Preface by M. Kotsyubynska. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2005, p. 974.

*Russification of Ukraine*. A popular science collection. Kyiv: Published by the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America, 1992, pp. 346–347.

Kasyanov, Heorhiy. *Nezhodni: ukrainska intelihentsiia v rusi oporu 1960-80-kh rokiv* [The Dissenters: The Ukrainian Intelligentsia in the Resistance Movement of the 1960s–80s]. Kyiv: Lybid, 1995, pp. 71–72.

Plakhotniuk, Mykola. “The Twenty-Second of May (A Memoir).” *Chas*, no. 19 (150), May 15, 1997; no. 20 (151), May 22, 1997.

KHPG Archive: Interview with V. Mohylny on January 13, 2000; V. Mohylny’s creative evening on November 21, 1999.

Ovsiienko, Vasyl. “Island of Independence.” In: *Svitlo liudei: Memuary ta publitsystyka* [The Light of People: Memoirs and Publicism]. In 2 vols. Vol. II. Compiled by the author; cover design by B. Ye. Zakharov. 2nd ed., expanded. Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2005, 352 pp., illus. (Additional printing: Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; Prava Liudyny, 2007), pp. 99–101.

MOHYLNYY VIKTOR MYKOLOVYCH

MOHYLNYY VIKTOR MYKOLOVYCH