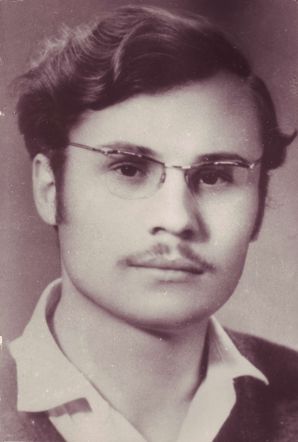

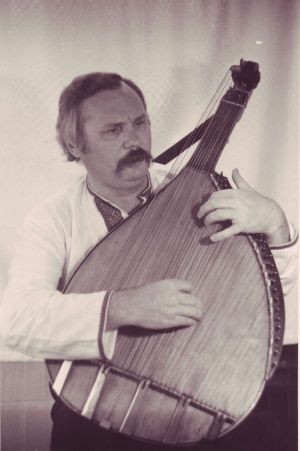

MYKOLA STEPANOVYCH LYTVYN (b. March 4, 1943, in the village of Fedorivka (Pomichna station), Novoukrainka Raion (now Dobrovelychkivka Raion), Kirovohrad Oblast. Kobzar, composer, writer, and journalist.

His father, Stepan Andriyovych (1904–1963), was a railway worker at Pomichna station; his mother, Mariya Onyskivna (1910–1974), was a collective farm worker who had 12 children. Four survived: Ivan, Olha, Vasyl, and Mykola. While still a schoolboy, Mykola contributed to the district newspaper as a rural correspondent. He sang with his brother Vasyl in amateur artistic groups. In 1961, both entered the Krolevets Vocational School of Artistic Weaving.

At a concert by the bandura players' chapel of the local weaving factory in the city's House of Culture, when they began to sing “My Thoughts, My Thoughts,” the brothers met their destiny. “It was a shock,” recalls Mykola. “I no longer knew where I was, in what time... Shevchenko himself came up to me and laid his hand on my head...” The boys met the chapel's director, Mykhailo Biloschapka, and asked to become his students. Three months later, their teacher took the brothers to the Reinhold Glière Kyiv Music College.

At the entrance exam, they sang “Oh, Moroz, Morozenko” so fervently that the admissions committee stood up. And though the boys did not know musical notation, they were accepted into the college as an exception. They studied there from 1961 to 1963. At night, they earned money for bread by unloading train cars and working as stokers. It was then that Mykola copied out the uncensored poems of Vasyl SYMONENKO. A true university for the brothers was their journey with the student choir “Zhaivoronok” (Skylark), led by Borys Ryaboklyach, through Shevchenko's lands in 1962. The young men and women walked from Moryntsi to Kaniv, giving 24 concerts along the way. In a report about this by V. SYMONENKO in the “Robitnycha Gazeta” (Worker's Newspaper), the bandura players Vasyl and Mykola Lytvyn were also mentioned. The poems that SYMONENKO read that evening impressed Mykola so much that he immediately went to Shevchenko's grave and spent the entire night there. Wishing to learn how to sing folk *dumy* (epic poems), Mykola became acquainted with Antonina Holub, the great-granddaughter of the kobzar Ostap Veresai and a graduate of the Kyiv Conservatory.

When she was sent to the Solomiya Krushelnytska Ternopil Music College in 1963, Mykola transferred to Ternopil as well to become a student in her class. He graduated from the college in 1965. Meanwhile, Vasyl temporarily left his studies to earn a living for himself and his brother. In Ternopil, Mykola befriended the archaeologist and art historian Ihor Gereta. Patriot-minded young people would gather at his home to read literature published abroad and *samizdat*. During the arrests of the Ukrainian intelligentsia on August 27, 1965, I. Gereta was arrested in Odesa, his brother Oleh in Ternopil, and Lytvyn in Kyiv. His poems were confiscated. A search of his mother's house in Pomichna lasted almost a full day. Rumors spread that Lytvyn was a terrorist preparing an assassination attempt on Brezhnev and that a bomb had been found in his mother’s house. He was accused of creating a nationalist organization and conducting “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” for singing “Ukraine Has Not Yet Perished,” as well as Sich Riflemen and insurgent songs he had learned from I. Gereta's father. He spent a month in the pre-trial detention center of the Ternopil KGB.

Finding insufficient evidence of “criminal activity,” they released him a month later without a trial, after forcing him to promise not to fight against the Soviet government. Despite “recommendations from above,” he was admitted to the Mykola Lysenko Lviv State Conservatory in 1966 to study the bandura, thanks to patriotically-minded professors (foremost among them, Roksoliana Zorivchak). In Lviv, the student found himself in the sphere of influence of now-famous artists and politicians—Ihor and Iryna KALYNETS, Vyacheslav CHORNOVIL, Stefania SHABATURA, Yaroslav Kendzior, Mykhailo KOSIV...

After graduating from the conservatory in 1971, Lytvyn was invited to work at the newly created Kyiv Orchestra of Ukrainian Folk Instruments under the direction of Yakov Orlov. He studied under the kobzar Yevhen Adamtsevych, was a guide for Oleksandr Markevych, and also knew Heorhiy Tkachenko. At that time, he submitted a collection of poems, *Vitryaky* (Windmills), to a publishing house, which Mykola Vinhranovsky blessed with a favorable review (it was, however, not published for another 17 years, in 1988). The repercussions from his time in Ternopil and Lviv followed Mykola; he did not last long in Kyiv. He lived without a residence permit with his brother Vasyl in the village of Ivankiv, Boryspil Raion, and later in Kyiv in a semi-basement room. The duet of Mykola and Vasyl Lytvyn gained great fame at that time.

Mykola’s songs with lyrics by V. SYMONENKO (“There, in the Steppe”) and Stepan Rudansky (“Hey, Cossack Brothers, Saddle Your Horses!”) were popular. His brother Vasyl and his mother moved to the village of Hrebeni near Kyiv. But Mykola was not granted a residence permit there either and, consequently, could not find work anywhere. After many unsuccessful attempts to find a job in the capital, he became a bandura teacher at the Sumy Music College in 1973. Due to his unsettled life, his first marriage fell apart. He returned to Kyiv in 1975. The artist and poet-translator Mykola Kabalyuk helped him, teaching him the profession of a graphic artist, which allowed him to earn a living even without a residence permit.

He married (in 1977) Lesia Kosovska, a cousin of political prisoners Volodymyr Kosovsky and Olha Mykhailychenko. They lived in a nine-square-meter dormitory room. He was fortunate to meet good and courageous people: writers Dmytro Cherednychenko, Vasyl Shklyar, and Volodymyr Burban helped him get a freelance correspondent position at the magazine *Ranok* (Morning) in 1979. In 1983, writer Oleksandr Klymchuk hired him as senior editor of the literature department at the magazine *Ukraina*. He worked there until 1988.

Lytvyn came into his own in the 1980s and 1990s, at the turn of an era. He appeared as a kobzar in the films *Nazar Stodolya*, based on the play by T. Shevchenko; *A Terrible Vengeance*, based on the works of N. Gogol; and in Stanislav Chernilevsky’s film about Vasyl STUS, *A Black Candle on a Bright Road* (1992). He also played a kobzar in the I. Franko Theater production *It Would Seem, Just One Word...*. In 1987, Lytvyn’s collection of stories and novellas, *Zori na dni krynytsi* (Stars at the Bottom of the Well), was published, followed in 1988 by the poetry collection *Vitryaky* (Windmills), and in 1990 by the collection of novellas *Hey, lety, pavutyno!* (Hey, Fly, Spiderweb!). He published a series of articles in books, journals, and newspapers about Ukrainian kobzars and composers Artem Vedel, Denys Sichynsky, and Mykola Leontovych. In 1994, his essay-novella *Struny zolotii* (Golden Strings)—about the origins and history of Ukrainian kobzar art—was published. This was followed by the book of musical works *Pisni voli* (Songs of Freedom) in 1995, the novella *Artem Vedel. The Mighty Spirit of Mazepa* in 1997, the poetry collection *Irzhannia strynozhenykh konei* (The Neighing of Hobbled Horses) in 2004, the documentary novella about Ihor Gereta, *Vse plyve* (Everything Flows), in 2008, and the book of poetry and diary entries *Leleka Pelazh* (The Stork Pelasgus) in 2009. In October 1990, the kobzar supported the student hunger strikers with his songs during the Student Revolution on Granite. Before the 1991 independence referendum, he traveled with his bandura across almost all of Ukraine, performing with I. Gereta in a program titled *Songs of Freedom* in Novomoskovsk and Luhansk, among other places. His songs were also heard in Poland, Slovakia, Germany, France, Lithuania, Russia, and the USA.

He revived old *dumy* and created new songs, such as “Don't Trust Moscow, for Betrayal Will Follow!” with lyrics by H. Petruk-Popyk (1992) and “According to the Eyewitness Chronicle” with lyrics by V. STUS. His songs are revolutionary, calling for a fight. On October 27, 1997, Lytvyn sang at the site of the 1937 execution of the Solovki transport in the Sandarmokh tract (Karelia). From 1991 to 1993, he was head of the art department at the magazine *Silski Obrii* (Rural Horizons); from 1993 to 1997, he was an observer for the all-Ukrainian farmers' newspaper *Nash Chas* (Our Time); from 1997 to 1998, he was deputy editor-in-chief of the newspaper *Slovo Prosvity* (Word of the Enlightenment); and in 1998, he was editor-in-chief of the newspapers *Visti z Ukrainy* (News from Ukraine) and *Ukrainsky Forum* (Ukrainian Forum). He is a member of the Union of Journalists of Ukraine (1985), the Union of Writers of Ukraine (1988), and the Union of Kobzars of Ukraine (2000). He is a laureate of the I. Nechuy-Levytsky All-Ukrainian Literary and Artistic Prize (1993) and the Olena Pchilka All-Ukrainian Literary Prize (1995), and was named an Honored Artist of Ukraine (2009). In 1993, the Ternopil Regional Council of People's Deputies established a scholarship in Mykola Lytvyn’s name for bandura students at the Ternopil Music College and for students from Ternopil studying the bandura at universities in Ukraine. He lives and works in Kyiv.

Bibliography:

I.

Lytvyn, M. *Zori na dni krynytsi* [Stars at the Bottom of the Well]. Kyiv: Radianskyi Pysmennyk, 1987, 286 pp.

Lytvyn, M. *Vitryaky* [Windmills]. Kyiv: Molod, 1988, 56 pp.

Lytvyn, M. *Lety, pavutyno!* [Fly, Spiderweb!]. Kyiv: Dnipro, 1990, 255 pp.

Lytvyn, M. *Struny zolotii: povist-ese* [Golden Strings: An Essay-Novella]. For middle school age. Kyiv: Veselka, 1994, 118 pp. (About the author: Mykola Shudrya, “Oh, the Cossack Virlo Can Be Heard from Afar…,” pp. 113–117).

Lytvyn, M. *Pisni voli* [Songs of Freedom]. Ternopil: Zbruch, 1995, 126 pp.

Lytvyn, M. *Irzhannia strynozhenykh konei* [The Neighing of Hobbled Horses]. Ternopil: Pidruchnyky i posibnyky, 2004, 116 pp. (About the author: Dmytro Pavlychko, “Mykola Lytvyn Sings,” pp. 104–105; also in *Literaturna Ukraina*, January 11, 2001; Dmytro Cherednychenko, “Mykola from the Ukrainian Steppe,” pp. 100–104; also in *Silskyi Chas*, February 9, 2001).

Lytvyn, M. *Vse plyve: dokumentalna povist* [Everything Flows: A Documentary Novella]. Ternopil: Terno-hraf, 2008, 68 pp.

Lytvyn, M. *Leleka Pelazh* [The Stork Pelasgus]. Ternopil: Mandrivets, 2009, 296 pp.

“Mykola Lytvyn's String: ‘I Do Not Yet See in the Actions of the New Government the Ukraine I Fought For.’” Interview by Mariya Lytvyn. *Den*, no. 119, July 7, 2005: http://www.day.kiev.ua/290619?idsource=144565&mainlang=ukr

Lytvyn, M. *The Executed Congress of Kobzars*: http://barvinok.ucoz.net/publ/istorija/rozstriljanij_z_39_jizd_kobzariv/4-1-0-80; Also in *Krymska Svitlytsia*, no. 36, September 4, 2009.

II.

Kosiv, M. “You Don’t Have to Praise It, But Do Read It…” *Kyiv*, 1988, no. 10.

Pravdyuk, O. “Kobzar Art in the Shevchenko Jubilee Year.” *Bandura* (New York), 1990, nos. 31–32.

Gereta, I. “Kobzar.” In Mykola Lytvyn, *The Neighing of Hobbled Horses*. Ternopil: Pidruchnyky i posibnyky, 2004, pp. 97–100.

Shudrya, M. “Oh, the Cossack Virlo Can Be Heard from Afar…” In Mykola Lytvyn, *Golden Strings*. Kyiv: Veselka, 1994, pp. 113–117.

Pavlychko, D. “Mykola Lytvyn Sings.” *Literaturna Ukraina*, January 11, 2001; also in M. Lytvyn, *The Neighing of Hobbled Horses*. Ternopil: Pidruchnyky i posibnyky, 2004, pp. 104–105.

Cherednychenko, D. “Mykola from the Ukrainian Steppe.” *Silskyi Chas* newspaper, February 9, 2001; also in M. Lytvyn, *The Neighing of Hobbled Horses*. Ternopil: Pidruchnyky i posibnyky, 2004, pp. 100–104.