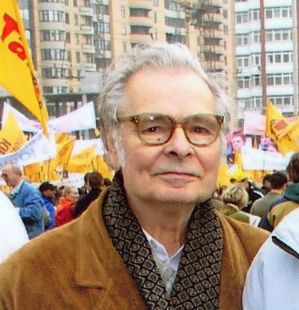

ZAVOYSKY, VOLODYMYR MYKOLAYOVYCH (b. March 3, 1932, Kyiv - d. October 18, 2006, Kyiv).

Geophysicist, member of the Club of Creative Youth, coordinator of the “Zhaivoronok” (Skylark) choir. He produced and distributed samvydav. Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences.

His parents were from the village of Dzhvinkove in the Vasylkiv district of the Kyiv region. His mother had no education, while his father graduated from the Kyiv Institute of Public Education and was killed at the beginning of the war in 1941.

After graduating from school in 1952, Zavoysky entered the geology faculty of Taras Shevchenko Kyiv State University. He communicated with Petro Boiko, a radio announcer, who convinced him that the Ukrainian cause was not entirely lost, something Zavoysky had doubted. He graduated from the university in 1957. He worked for two years in the Kyiv Geological Trust in Polissia.

Returning to Kyiv in 1959, he began attending events organized by the Club of Creative Youth (KTM). An evening dedicated to Lesia Ukrainka in a park, illuminated by lit newspapers, was particularly memorable. He listened to Mykhailo Braichevsky’s lectures on history. At the KTM, he met Borys Ryabokliach and Vadym Smohytel, the organizers of the amateur “Zhaivoronok” choir (autumn 1961) at the Kyiv Conservatory. Its core consisted of students and workers who saw their mission in popularizing Ukrainian song. It was a traveling choir, ready to perform anywhere and under any circumstances. The choir made several trips: to Trakhtemyriv, Pyliavtsi, Kaniv, and Cherkasy. Since Zavoysky loved Ukrainian songs, he began attending rehearsals and concerts.

He became acquainted with the choir's artistic director, Ionych, ethnographer Erast Biniashevsky, Nadiia Svitlychna, and became friends with Oleksandr Martynenko. When a conflict between Ryabokliach and Ionych threatened to split the choir, Zavoysky, along with Martynenko, set out to save it. They visited choristers in student and worker dormitories, recruiting new members. They saw the choir as an instrument, an environment for awakening national self-awareness and disseminating samvydav literature. When Ionych left the choir, Vadym Smohytel led it for a while, but when he too faced pressure at the conservatory, he stepped down. Zavoysky then turned to Ihor Poliukh, the head of the choir at the Institute of Foreign Languages, asking him to take on “Zhaivoronok,” and invited Olya Liforenko, a first-year piano student at the conservatory, to be the concertmaster. They were talented and highly cultured people.

Samvydav literature was circulated in this environment, primarily typewritten and photocopied poems by young poets like Ivan Drach, Borys Mamaisur, Mykola Kholodnyi, and Vasyl Symonenko. The choir members attended debates on national issues held at the university. Of course, the KGB had its agents everywhere. Persecution began. The House of Scientists at 42 Volodymyrska Street stopped providing the choir with rehearsal space. Other institutions also refused. Eventually, the choir had to gather on the slopes of the Dnipro River. It performed less frequently, drew smaller crowds, and by 1965, it had effectively disbanded. Zavoysky also abandoned this effort, as he had to prepare and defend his dissertation.

The remnants of “Zhaivoronok” joined the “Vesnianka” choir at Kyiv University, led by Volodymyr Nerodenko. Zavoysky was widely acquainted with the Sixtiers, visited Alla Horska's studio and Ivan Svitlychny's apartment, and attended Svitlychny's lectures on aesthetics. He knew Vasyl Stus, Viacheslav Chornovil, and Ivan Rusyn.

During the celebration of the 150th anniversary of Taras Shevchenko’s birth in March 1964, Zavoysky happened to be present at the destruction of a stained-glass window in the university’s vestibule (created by Alla Horska, Panas Zalyvakha, Liudmyla Semykina, Halyna Sevruk, and Halyna Zubchenko), which was ordered by Academician I.T. Shvets, the rector of Taras Shevchenko Kyiv State University. He saw how brutally Academician A.D. Skaba, a secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, was swearing.

Zavoysky had a camera and an enlarger. Through O. Martynenko, who lived with him for a time, he met Yevhen Proniuk, from whom he received samvydav manuscripts and books from foreign publishers, which he photographed and reproduced. The flow was so great that he sometimes didn't have time to read everything himself: he would receive a text in the evening and return the prints in the morning. One notable book was “On the Crimson Horse of Revolution,” which contained data on the repression of the Ukrainian intelligentsia. Y. Proniuk and O. Martynenko were very active in distributing samvydav literature. This flow stopped with the beginning of the arrests in August 1965.

On September 4, 1965, Zavoysky attended a screening of the film “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors” at the “Ukraina” cinema and, of course, stood up with those protesting the arrests of the Ukrainian intelligentsia.

Zavoysky’s apartment was searched twice, but no samvydav was found—he had hidden everything in time. Only a foreign-published book by Sofia Rusova and poems by V. Symonenko were confiscated. He was interrogated in the cases of O. Martynenko, I. Svitlychny, and Mykola Hryn (with whom he worked at the Institute of Geophysics). Zavoysky did not testify against anyone, either during the investigation or at Hryn's trial. In March 1966, Hryn, from whom a large amount of samvydav had been seized, was sentenced to 3 years, but in view of his repentance, the Supreme Court changed the sentence to a suspended one. In this connection, a meeting was held at the Institute of Geophysics to condemn Hryn and Zavoysky. Before the meeting, KGB officers gave a “dressing-down” in the director's office, stating, “Zavoysky is fully culpable of a crime.” His dissertation advisor, Zinaida Oleksandrivna Krutykhovska, was asked, “How do you feel about him speaking Ukrainian?” She replied, “Actually, I quite like that he speaks Ukrainian.” At the meeting, Hryn tried to justify himself, while Zavoysky only managed to squeeze out one sentence: “I am not a nationalist.” The famous theorist of Russification, Academician I.K. Bilodid, spoke: “You see, we have found defenders of the Ukrainian language! Found them! They themselves can’t string two words together in Ukrainian, yet they babble on…” Silence fell. Then, the engineer and writer Yuriy Khorunzhyi spoke up: “Why do you say that in vain? Zavoysky speaks Ukrainian very beautifully!”

After this, Zavoysky focused on his scientific work, defending his candidate dissertation, “The Origin of Remanent Magnetization of Rocks of the Ferruginous-Siliceous Formation.” This was supported by Z.O. Krutykhovska and the director of the Institute of Geophysics, Serafim Ivanovich Subbotin. In 1999, he defended his doctoral dissertation, “Magnetic Anisotropy of Rocks and Its Use for Solving Structural Problems.”

Although Zavoysky did not show any particular activism after 1965, the surveillance on him continued until perestroika. For instance, when the arrests of members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group began, Zavoysky was summoned to the institute's first department and shown photos of people allegedly suspected of murder. In reality, this was how they took his fingerprints.

In the 1960s–1980s, Zavoysky provided shelter in his home to young poets such as Viktor Kordun, Borys Mamaisur, and others.

During the perestroika era, he established a branch of the Narodnyi Rukh Ukrayiny (Rukh) at the Institute of Geophysics. He preserved and transferred many samvydav materials to the Museum of the Sixtiers Movement.

Bibliography:

1.

Zavoysky, Volodymyr Mykolayovych. Subbotin Institute of Geophysics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Magnetic Anisotropy of Rocks and Its Use for Solving Structural Problems. Synopsis of the dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences: 04.00.22 / — Kyiv, 1999. — 34 pp. — In Ukrainian;

Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group Archive: Interview on May 27, 1999.

2.

Bazhan, O.H. The Opposition Movement in Ukraine (Second Half of the 1950s–1980s). Dissertation for the degree of Candidate of Historical Sciences: 07.00.01 / National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. — Kyiv, 1996. — 193 pp.

Bazhan, Oleh. “Kulturno-prosvitnytskyi rukh yak odna z form oporu politytsi rusyfikatsii Ukrayiny v 60–80-kh rr.” [The Cultural and Educational Movement as a Form of Resistance to the Policy of Russification of Ukraine in the 1960s–80s]. Zapysky no. 3, pp. 123-127 (http://www.library.ukma.kiev.ua/N2/NZV3_1998_histori/16_bazan_o.pdt)

Vasyl Ovsiienko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, March 14, 2009. Corrected by the widow Iryna Mykolaivna Ivashchenko on November 1, 2010.

Photograph from 2002.