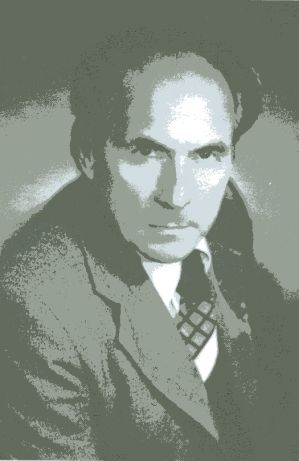

IVAN FEDOROVYCH HNATIUK (b. July 21, according to documents July 27, 1929, in the village of Dzvyniacha, Kremenets County, Volhynian Voivodeship (now Zbarazh Raion, Ternopil Oblast)–d. May 5, 2005, in the city of Boryslav, Lviv Oblast).

A member of the resistance movement, a political prisoner, a poet, and a laureate of the Taras Shevchenko National Prize.

His father, Fedir Hnatiuk, son of Ivan, was from a poor peasant family (1904–May 1, 1945). His mother, Varvara (November 25, 1906–July 2, 1990), was the daughter of a prosperous farmer, Pavlo Yurchun, who was elected village elder several times. They married against her parents' will. Fedir built stoves in the surrounding villages and wove baskets in the winter. Varvara wove linen and rugs for people. They built a house on their own. The children were taught to work from a young age.

Ivan took after his great-grandfather, an opryshok who burned down manor estates and was exiled to Siberia for it: he was disobedient and stubborn in his obstinacy, for which he was often beaten. As a child, he had a slight stutter.

When the Bolsheviks arrived in 1939 and began to create collective farms, his father flatly refused to apply to join. He also forbade his son from joining the Pioneers. First, the Polish settlers were deported from the village to Siberia, then they turned to the Ukrainian intelligentsia and conscious peasants. That is why the peasants met the Germans in 1941 with hope. His father brought terrible news from the neighboring town of Vyshnivets: the Germans had uncovered an NKVD dungeon filled with tortured bodies.

With a primary education, Ivan went to the Vyshnivets vocational school to train as a carpenter. He lived in a dormitory. He read a great deal of patriotic literature, in particular, the stories of Yuriy Horlis-Horsky and Andriy Chaikovsky, which inspired him to suffer for his people and perform spiritual feats. The eldest among the students, Ivan Sedletsky, read aloud the Decalogue—the 10 commandments of a nationalist—which they all repeated and memorized. In the last year and a half of the German occupation in Volyn, the authority was practically Ukrainian, not German. Ivan witnessed battles between insurgents and German occupiers and Polish policemen.

During Lent in 1944, Ivan fell gravely ill with typhus and barely survived. In the autumn of 1944, his father was mobilized into the Soviet Army and was killed on May 1, 1945, on the last day of the Battle of Berlin. His mother was left with four children. Ivan was the head of the household. As a 15-year-old, he was already receiving tasks from the insurgents, delivering underground messages. He first ran into an ambush in the autumn of 1944. He got away with a severe beating—the village council chairman stood up for him, saying his father was in the Soviet Army.

In the winter of 1944–45, NKVD raids became more frequent, with teenagers and the elderly becoming victims. Ivan was detained nine times for several days—and each time he was mercilessly beaten: “What, that stutterer from Dzvyniacha again? No matter how much you beat him, you won't get a word out of him. And he won’t even groan, the bastard!” Teenagers were forced to join the ‘strybky’—‘extermination squads’—to fight against the UPA. Ivan deliberately injured his leg with some corrosive liquid, and the leg swelled up. However, he was eventually taken to a ‘strybky’ school in Vyshnivets, where he wasted a year and a half. He escaped this predicament when, on the eve of 1947, insurgents disarmed the ‘strybky,’ and the militia, after holding them under arrest for two or three days, beat them and dispersed them.

In September 1946, Ivan enrolled in the 5th grade of the Vyshnivets school, attending classes with a light machine gun. Having graduated from the 5th grade with honors, he added the number II to his report card and honor certificate and sent the documents to the Kremenets Pedagogical College, where he was accepted without entrance exams. Over two summer months, he caught up on subjects he hadn't studied and was an excellent student from the first quarter. He loved mathematics and began to write poetry.

In his first year, Ivan was summoned to the local NKVD and questioned about a pistol he had in 1942. The OUN leadership of the Pochaiv district instructed him to transport and distribute leaflets. He adopted the pseudonym “Ivan Nedolia” (Ivan Ill-fate), which he used to sign his reports (‘kvestionary’) and his poems. At the beginning of his second year, he spoke out at a meeting against joining the Komsomol, for which the Komsomol organizer Vasilyev called him a “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalist.” A few days later, Ivan was arrested. As machine-gunners led by investigator Mogilevsky were taking him to prison, he jumped over a wall and escaped. He ran home, took some clothes, kissed his mother's hands and the threshold of his home, and went into the underground. He spent his nights in haystacks and barns. He asked for permission to go into hiding, but the underground leadership persuaded him to continue his studies. A classmate, a friend, forged a registration card, and he was accepted into the Brody Pedagogical College in the Lviv Oblast. But three weeks later, on December 27, 1948, his youth was cut short by a new arrest, right in the college.

Hnatiuk was held in the Kremenets prison. Investigators Kravchenko and Mogilevsky beat him severely, even simulating his execution. He “celebrated” Christmas 1949 by standing for two weeks in a narrow “box” cell. Senior Lieutenant Gorbachev, an investigator, presented Hnatiuk with his blood-stained ‘kvestionar’ and a photo of his murdered friends propped up against a wall, including his dearest friend Vasyl Tesliuk. This shocked Hnatiuk so profoundly that he remained unconscious for a long time, lost the ability to sleep, and from then on, for 22 years, he periodically suffered from insomnia for two to three months at a time.

On January 20, 1949, investigator Bezshchasnyi formulated the indictment in case No. 7426, stating that student Ivan F. Hnatiuk was a member of the OUN, served as an informant for the Pochaiv district OUN leadership under the pseudonym “Ivan Nedolia,” collected intelligence, distributed leaflets, recruited others into the OUN, and agitated students not to join the Komsomol. He was charged under Articles 54-1(a) and 54-11 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR (“treason” and “armed struggle”). During the most brutal four-month interrogations, he did not betray anyone.

On March 31, 1949, Hnatiuk’s case was transferred to the Military Tribunal of the MVS Troops of the Ternopil Oblast. As a farewell, the head of the operational group, Captain Yermolayev, beat him severely. However, Hnatiuk went to the tribunal with his head held high, as if he “was being led not to a tribunal session, but to a wedding.” The Komsomol organizer from the college, Vasilyev, and a physics teacher, Tatyana Sinyarova, were called as witnesses; Sinyarova uttered only two words: “I don't know.” Taking into account the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of May 26, 1947, “On the Abolition of the Death Penalty,” the tribunal, composed of Senior Lieutenant of Justice Vasylishyn and two women, Junior Lieutenant of the Militia Rudenko and Babenko, without the participation of a prosecutor or a defender, sentenced Hnatiuk to 25 years of imprisonment with confiscation of property and 5 years of disenfranchisement.

Hnatiuk was transferred to Lviv and sent east on a transport that lasted a month. In the heat, they were fed salted herring and sticky bread, with very little water. At transit prisons, the authorities deliberately pitted political prisoners against ‘suki’ (inmates collaborating with the administration), leading to bloody fights.

In September, Hnatiuk was taken by the steamship “Nogin” from the port of Vanino to the Magadan Oblast. His first camp was Arkagala, where the poet Mykhailo Dray-Khmara had been executed some ten years earlier. He worked in a mine for a year. The work, including roll calls and searches, took 14 hours a day, leaving only 5-6 hours for sleep. Prisoners were dying en masse from exhaustion, hunger, and cold. Hnatiuk then refused to do underground work and spent 17 days in a cold punishment cell. A female doctor, surprised he was still alive, got him out.

In the autumn of 1949, Hnatiuk wrote his first poem in captivity, “A Tragic Generation.” Poetry was his support: “If I don't write poems, I will soon die.”

A year later, Hnatiuk was moved to the “Alyaskitovo” concentration camp of the Berlag administration—at the end of the Kolyma Highway, 1,200 km from Magadan. He worked in a mine in blinding dust. There he befriended Volodymyr Sorokalit and poets Hryhoriy Chaplya and Mykola Voloshchuk. He fell ill with tuberculosis. He was treated only with calcium chloride, then sent to the Debin settlement on the left bank of the Kolyma River. Conditions there were better; his tuberculosis and stomach ulcer were treated, and he had an appendectomy. He was sent back to the “Kholodny” camp to mine gold. For not reporting to work on Christmas Eve 1953, he was thrown into a punishment cell, where guards choked him six times and revived him with water. He then received 6 months in a BUR (strict-regime barracks).

On March 6, 1953, Hnatiuk wrote the poem “On the Death of a Tyrant” and read it aloud—this was heard by V. ROMANIUK, the future Patriarch Volodymyr. He was transferred to the “Dniprovsky” camp, where he was again in the BUR. In total, he was held in two prisons, three transit centers, and five Kolyma camps. He spent 1.5 years in the Belov camp. There, after Stalin’s death, conditions were easier; he read and wrote a great deal, and from there he sent a letter to his mother to let her know he was alive, as she had been mourning him as dead for three years. He communicated here with the commander of a UPA unit, Omelian Polovyi, and a professor at the University of Berlin, Mykhailo Antonovych. He was treated in the Matrosov settlement (where V. STUS would later be imprisoned from 1977–79). He suffered severe hemorrhages from his lungs. He was finally granted a Group II disability status and on February 6, 1956, he was released “on the basis of the Magadan Oblast court ruling of November 10, 1955, as someone suffering from a severe illness.” Political prisoners released for health reasons were only freed on the condition that a relative, through the All-Union MVS, would provide written consent to take them in and care for them until death. Such a certificate of consent was given to Hnatiuk by his future wife, Halyna Kapustiak, whom he had met by chance in 1954 after her release from Berlag and had one visit with.

Hnatiuk first went to his mother and sisters, who had been exiled to the Mykolaiv Oblast, but after two or three days, the local policeman ordered him to go to his designated place of residence, Boryslav in the Lviv Oblast, to Halyna. On April 1, 1956, they were married. He visited his home village of Dzvyniacha and was struck that his fellow villagers who remained had already adapted to the new life: “We have bread and vodka—what more do we need?” But when Soviet tanks crushed neighboring Hungary, the KGB forced Hnatiuk to leave Western Ukraine, threatening to fabricate a criminal case or even murder him.

In the spring of 1957, Hnatiuk said goodbye to his wife and daughter Liuba (b. 1957) and went to his mother in the village of Puzyri, Zhovtnevyi Raion, Mykolaiv Oblast. He buried the poems he brought from Kolyma. Despite suffering from tuberculosis, he found a job as a bookkeeper at the “Prybuzky” state farm, where his mother and sisters worked. KGB agents came and tried to recruit him as an informant. For refusing, he was fired, then given a job as a grain weigher so they could catch him on a shortage. Later he worked as a bricklayer and a loader. His wife and children (son Volodymyr was born in 1959) moved to join him. Hnatiuk was summoned to the KGB in connection with the arrests of former political prisoners Mykola Voloshchuk and Volodymyr Sorokalit, and his home was searched, during which his correspondence with them was seized. His arrest was likely averted by a serious operation during which two-fifths of his lung was removed.

After a three-year ordeal in the southern steppes, seeing the clear hopelessness of a former political prisoner's situation, confirmed by the chief physician of the Mykolaiv regional tuberculosis hospital, the KGB allowed Hnatiuk to return to Boryslav. But before that, a KGB officer, Georgy Ivanovich Belyachenko, who boasted of having been Dmytro Pavlychko's investigator and getting him to write a cycle of poems against Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists, “The Murderers,” proposed that Hnatiuk also write poems “condemning the past.” It was a choice: to live or to die. Severely exhausted by his illness, Hnatiuk made a compromise: three or four such poems were published in the autumn of 1960 in the Boryslav newspaper *Prykarpatska Pravda*. In the early 1960s, as part of a group of “representatives of the Lviv Oblast public,” which included publicist Taras Myhal and former political prisoner Luka Pavlyshyn, he was taken to Mordovian camps for the purpose of “re-educating” the unrepentant. Prisoner Trokhym Shynkaruk accused him: “You have bartered away the honor of a political prisoner.” (In 2001, Hnatiuk published a posthumous collection of T. Shynkaruk's poems). However, during interrogations in the cases of B. HORYN and M. OSADCHY in 1965, he did not provide the testimony the KGB needed.

In 1964, Hnatiuk was given a job as the manager of the city bookstore in Boryslav. There he met Kuzma DASIVY, who was later imprisoned (in 1973).

Hnatiuk’s poems occasionally began to appear in newspapers and magazines, although most remained unpublished. He participated in the literary association meetings at the city newspaper's editorial office. From 1964, his publications became more frequent. In 1965, the “Kamenyar” publishing house released a small collection of 27 poems, “Pahovinnia” (New Growth). His book “Kalyna” (Viburnum) (1966), which contained not a single line to please the authorities, was declared “nationalist” at a meeting of the Central Committee of the Komsomol of Ukraine, which affected the author's future. When the Lviv organization of the Union of Writers of Ukraine voted in 1966 to admit Hnatiuk to the Union, the then-secretary of the Lviv regional committee, V. Malanchuk, declared at a meeting of communist writers that he would not forgive them for “smuggling a nationalist into the Union.” The matter dragged on for a year and a half, and he was only admitted to the Union on December 27, 1967.

Since Hnatiuk’s name was mentioned in foreign radio broadcasts and publications, a collection of his poems, “Sledy” (Traces), was published in Moscow in Russian translation, though mercilessly mutilated by censorship. KGB officers talked of including Hnatiuk in the Ukrainian SSR delegation to the UN.

He slowly entered the circle of writers, aided by vouchers to the writers' retreat in Irpin. He was on friendly terms with Volodymyr Luchuk and Volodymyr Pidpaly, who edited his books, and with Borys Kharchuk. The collections “Povniava” (Fullness) (1968), “Zhaha” (Thirst) (1970), “Zhyttia” (Life) (1972), “Barelyefy Pamiati” (Bas-reliefs of Memory) (1977), “Doroha” (The Road) (1979), “Chornozem” (Black Earth) (1981), “Turbota” (Care) (1983), “Osinnia blyskavka” (Autumn Lightning) (1986), “Blahoslovennyi svit” (Blessed World) (1987), a children's book “Khto naiduzhchyi na ves svit” (Who is the Strongest in the Whole World) (1989), and “Nove litochyslennia” (A New Chronology) (1990) were published.

Hnatiuk was a participant in the Constituent Congress of the People’s Movement of Ukraine (NRU). He was last beaten at the funeral of his friend V. ROMANIUK—Patriarch Volodymyr—on July 18, 1995.

After Ukraine’s independence, Hnatiuk's books “Pravda-msta” (Truth-Revenge) (1994), “Vybrani virshi ta poemy” (Selected Poems and Epic Poems) (1995), “Na tryzni lita” (At Summer’s Wake) (2003), and “Khresna doroha” (The Way of the Cross) (2004) were published. His poems, like the man himself, are sharp, maximalist, and uncompromising; they sound like a continuation of Shevchenko's passion. In 2000, for his memoir “Stezhky-dorohy” (Paths and Roads) (1998), Hnatiuk was awarded the Taras Shevchenko National Prize. He is also known as a translator of poetry and prose from Belarusian, Polish, and Sorbian languages.

He is buried in the city of Boryslav.

Bibliography:

1.

*Vybrani virshi ta poemy* [Selected Poems and Epic Poems]. Lviv: Chervona kalyna, 1995. 672 pp.

*Stezhky-dorohy. Spomyny* [Paths and Roads. Memoirs]. Drohobych: Vyd. firma “Vidrodzhennia,” 1998. 496 pp., ill.

*Bezdorizhzhia* [Roadlessness]. Kharkiv: Maidan, 2002. 240 pp., ill.

*Khresna doroha: Poetychni tvory* [The Way of the Cross: Poetic Works] / Preface by N. Kyrylenko. Kharkiv: Maidan, 2004. 820 pp.

*Svizhymy slidamy: Spohady, esei* [On a Fresh Trail: Memoirs, Essays]. Kharkiv: Maidan, 2004. 136 pp.

2.

Musiienko, Oleksa. “Ivan Hnatiuk.” *Literaturna Ukraina*, no. 28 (4437), July 11, 1991; also in: *Z poroha smerti. Pysmennyky Ukrainy – zhertvy stalinskykh represii* [From Death's Doorstep. Writers of Ukraine – Victims of Stalinist Repressions] / Author collective: Boiko L.S. et al. Kyiv: Rad. pysmennyk, 1991. Vol. I / Compiled by O.H. Musiienko, pp. 134-137.

KhPG Archive: Interview with I. Hnatiuk on October 11, 2000. KhPG Archive: Interview with I. Hnatiuk on 11.10. 2000. https://museum.khpg.org/1228861227 Sverstiuk, Y. “Tvoia mira pravdy: Pro spohady I. Hnatiuka” [Your Measure of Truth: On the Memoirs of I. Hnatiuk]. *Suchasnist*, 2001, no. 5, pp. 99–104. Tkachuk, Yarema. *Bureviyi. Knyha pamiati* [Storms. A Book of Memory]. Lviv: V-vo “SPOLOM,” 2004, pp. 115–120. *Mizhnarodnyi biohrafichnyi slovnyk dysydiv krajin Tsentralnoi ta Skhidnoi Yevropy y kolyzhnioho SRSR*. T. 1. Ukraina. Chastyna 1. [International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former USSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1]. Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny,” 2006. 1–516 pp.; Part 2. – 517–1020 pp.; Part 3. – 2011. – 1021–1380 pp.: Hnatiuk Ivan, pp. 1090-1093: https://museum.khpg.org/1228860599 *Rukh oporu v Ukraini: 1960–1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk* [Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960–1990. An Encyclopedic Guide] / Preface by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010. 804 pp., 56 ill.; Hnatiuk: pp. 141-142; 2nd ed., 2012. – 896 pp. + 64 ill.; Hnatiuk: p. 157. *Spohady pro Ivana Hnatiuka* [Memoirs about Ivan Hnatiuk] / Comp. P. Soroka. 2nd ed., expanded and supplemented. Ternopil: [Aston], 2010. 200 pp.

Tkachuk, Yarema. *Bureviyi. Knyha pamiati* [Storms. A Book of Memory]. Lviv: V-vo “SPOLOM,” 2004, pp. 115–120.

Koval, Roman. “Ivan Hnatiuk – poet-vershnyk. Do 75-richchia vid dnia narodzhennia” [Ivan Hnatiuk – The Poet-Horseman. For his 75th birthday]. *“Nezboryma natsiia”*, 2004, July.

Vasyl Ovsienko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, December 9, 2008. Last read on May 23, 2016.

14,370 characters