The last pilot of the Dnieper rapids, educator, regional historian, political prisoner.

From a family of hereditary pilots of the Dnieper rapids, fishermen, and farmers. Born 5 km from the Kodaksky rapid, he grew up to its roar. From a young age, he mastered all agricultural work. By 1921, he had completed a four-grade school, but he stopped his studies due to the famine. He managed to read Andrian Kashchenko’s books about the Cossacks—later, the Bolsheviks removed them from libraries. He led the drama circle of the *Prosvita* society.

He was naturally very strong and resilient. From 1926, he would go with his father through the Dnieper rapids in a *dub* (a large dugout canoe), worked as a rower on rafts, and at 19, he became the otaman (leader) of a raft, and at 21, a pilot’s assistant. It was then that he met Dmytro Yavornytsky. In 1932, he was supposed to pilot independently, but that year the rapids were flooded by the waters of the Dniprelstan (Dnieper Hydroelectric Station).

His religious father forbade him from joining the Komsomol. From 1929–1932, Omelchenko finished evening school while working on a collective farm without any pay. During the famine, he reached a state of extreme exhaustion. In 1932, he entered preparatory courses at the Institute of Professional Education (where he received 200g of bread), and then enrolled in the socio-economic faculty of Dnipropetrovsk University. When its geology and geography department was closed in 1935, he entered the same faculty at Kharkiv University. With his credits from Dnipropetrovsk, he graduated in 1937. He married a teacher, Oksana Yakivna Kovalenko; their son Oleksandr was born in 1938.

He was assigned to the Melitopol Agricultural Institute as a geology and geography instructor for evening courses. To get an apartment, he took on several hours of geography and astronomy at a secondary school. He became passionate about local history work with children. He was invited to the Zaporizhzhia Regional Palace of Pioneers, which was located in Melitopol. After three years, Omelchenko's group became first in the region and third in Ukraine, and was awarded a monetary prize and a two-week trip through Crimea. He was also a lecturer for the regional lecture bureau.

In 1940, Omelchenko was invited to teach geography at the Zaporizhzhia Pedagogical Institute, but since the faculty did not open, he worked at a school on Khortytsia Island. He wrote an essay and a series of articles about the island. He launched extensive local history work on Khortytsia, in particular, proposing to the regional department of education to organize a student expedition from Zaporizhzhia to Perekop, following in the footsteps of Wrangel. With his students, he walked from Khortytsia to the village of Bilenke, collecting rich historical, ethnographic, and folklore material. His school museum was richer than the regional ethnographic museum.

A week after the start of the war, he was mobilized. Since he had completed higher military training in “artillery” at the university, he served as a gunner in Sevastopol. He was subsequently transferred to the Kalinin, Baltic, and 3rd Ukrainian fronts. As a battery commander and lieutenant, he had to join the party in 1943. He participated in the breakthrough of the Romanian front and fought through Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Austria. He had medals for the capture of Budapest and Vienna, and suffered a concussion, which left him deaf in one ear. After the war, he was transferred to Bulgaria.

He was demobilized in 1946 and appointed director of the Bratske Pedagogical School in Mykolaiv Oblast.

In 1947, out of 120 correspondence students at the school, only 80 appeared for their session. They were swollen from hunger. A teacher in the village received 2.5 kg of flour per month, and nothing for dependents. Omelchenko himself and his wife, a teacher, were also living on the brink of starvation. He went to the villages to inspect the work of the correspondence-student teachers. He saw the widows and children of front-line soldiers swollen from hunger. Collective farmers received 60-70 grams of grain per workday. Arriving at the regional education department, Omelchenko saw a swollen woman with children and learned that the children were not being admitted to an orphanage, and he expressed his outrage. Back at his home, a similarly swollen woman came to his door asking for bread, but he had nothing to give her. The naive front-line veteran was so shocked that, after finishing his classes that same evening, he wrote a letter to the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), laying out specific facts about children dying of starvation: “It is impermissible for children to die—they are our future, our next generation. Take some measures.”

The authorities “took measures” three months later, just as Omelchenko had taken his wife to the maternity hospital: on October 27, 1947, he was arrested, and in February 1948, he was sentenced in Mykolaiv under Article 54-10 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (“anti-Soviet agitation”) to 10 years. Although this article did not provide for confiscation of property, during the search, the NKVD officers took and divided among themselves Omelchenko’s and his wife’s watches, which he had bought in Bulgaria, his wife’s gold tooth that had fallen out, his officer’s uniform and boots, and a presentation shotgun.

Omelchenko spent a month at a transit point in Dnipropetrovsk. In Omsk, he worked for a year in logging, then as a foreman of a construction brigade. He was then sent to a logging camp in the Argun River basin in the Khabarovsk Krai. He felled trees and built barracks and roads. He was later transferred to the construction of Komsomolsk-on-Amur as a plasterer and painter, then to a logging camp on Sakhalin Island. As an honest and literate man, he was put in charge of the timber exchange to stop a dd-padding and theft of lumber. Omelchenko handled it, and the camp commander gave him a good character reference, assuring him of an early release. Meanwhile, his brother, a colonel, could not advance in his career as a relative of an “enemy of the people.” He went for a meeting with S. Kovpak, the Deputy Chairman of the Presidium of the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian SSR, and told him about his brother’s case. Kovpak promised to help.

There were no newspapers, books, or radios in the camps, so so-called “novelists,” who could tell stories well, were popular among the prisoners. Omelchenko had broad knowledge, a good memory, imagination, and a talent for storytelling. He told stories about the Cossacks, particularly about the campaigns of Ivan Sirko, about the Dnieper rapids, about Suvorov, and Bagration, which earned him the respect of the prisoners.

As head of the timber exchange, Omelchenko had the right to leave the zone at any time. He brought forest berries to those sick with scurvy, as he himself had suffered from it twice. In the summer of 1953, while gathering berries, he noticed that they were unusually large in one spot. He fell through the ground—and discovered the decomposing bodies of executed prisoners. He said in the barracks: “These large berries are from the blood of our brothers.” An operative summoned him and ordered him to show where such large berries grew. “The bastards,” the operative said. “They did the deed but couldn't even hide it properly, the fools.” And he commanded: “Not another word about this to anyone. You blab, and you'll end up here too.”

A few days later, Omelchenko’s right to leave the zone was revoked, and he was scheduled for transport to Kolyma. As a geographer, he knew that the calm season on the Sea of Okhotsk was over and storms were beginning. Transport ships often perished. This was confirmed by experienced prisoners. Omelchenko agreed with several friends that they would refuse to go on the transport and demand the sanction of the supervising prosecutor. But on the day of the transport, his friends backed down. Omelchenko, however, did not respond when his name was called. The guards checked those who remained, found him, and began to drag him by force to the transport. But he clung to a tree: two men could not pull him away. When four men started to pull him, he hooked his hand around a root and held on to the last. When a guard dog bit him, the whole zone erupted in an uproar. The transport commander, amazed by his desperate struggle, asked why he did not want to go. Omelchenko said that he got seasick even in a car: if they needed his corpse, they could just shoot him here. With his short remaining sentence, he shouldn't be taken to Kolyma; he was supposed to be released soon. Besides, he had a premonition that this transport would perish at sea. The convoy commander said: “I'm not taking this man.” Indeed, the ship, carrying 1,650 prisoners, sank during a storm.

In March 1954, Omelchenko was released early with his conviction expunged. He returned to his native region, but he was not hired anywhere as a teacher. He worked in manual labor.

Only in 1961, after securing his rehabilitation, did Omelchenko become a teacher of geography and astronomy at an evening school in his home village, and two years later, its director. But not for long. One day during a break, a group of high school students approached him and asked if Hetman Mazepa was a traitor. The director said: “Mazepa never betrayed Ukraine.” He was summoned to the district party committee and dismissed from his post as director. Omelchenko went to teach at school No. 61 in Dnipropetrovsk, where he worked until his retirement in 1970.

Omelchenko socialized with the creative youth of the Dnipropetrovsk region, in particular, with Ivan SOKULSKY. His circle of acquaintances included Doctor of Philology Anatoliy Popovsky, local historian Mykola Chaban, academician Hanna Shvydko, as well as writers and historians.

Throughout the years, even after retiring, Omelchenko taught lessons and led circles on local history and ethnography in schools, vocational schools, and technical colleges. He gave individual lectures to students and fostered a love for their native land in children and youth. After independence, at his initiative, school No. 107 and kindergarten No. 270 in Lotsmanska Kamyanka switched to Ukrainian as the language of instruction and upbringing.

As early as 1985, Omelchenko wrote *Memoirs of a Pilot of the Dnieper Rapids*, excerpts of which were published in 1989 in the regional newspaper *Zorya* and in the Lviv journal *Dzvin*. The book was published in 1998 and 2000. In 1994, Omelchenko created a museum of the pilots in Lots-Kamyanka, for which, along with the book, he was awarded the D. Yavornytsky Prize by the regional branch of the Writers’ Union. He prepared the books *Recollections*, *Steppes of Ukraine*, and *Pilots of the Dnieper Rapids*. He was knowledgeable about gardening and herbs.

Omelchenko was a delegate to the Constituent Congress of the Society for the Ukrainian Language and its active member. In March 1989, the constituent meeting of the Sicheslav Regional Movement was held at his estate. He was the deputy head of the regional organization of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons and participated in the celebration of the 500th anniversary of the Cossacks in Kapulivka. He was held in high esteem, often invited to meetings, and his name was entered into the “Golden Book of Ukraine.”

Omelchenko’s wife passed away in 1995. He has sons, Oleksandr (b. 1938) and Volodymyr (b. 1947), and grandchildren Igor, Oksana, and Liliya, and great-grandchildren Myroslav, Ruslan, and Leonid—it was primarily to them that the old pilot addressed his memoirs.

Omelchenko is buried in the old cemetery in Lotsmanska Kamyanka, which has become part of Dnipropetrovsk.

Bibliography:

1.

“Through Stalin’s Death Camps.” Prepared by M. Chaban // *Prapor yunosti*. – June 10, 13, 15, 20, 22, 1989; Also: *Zona*, No. 13, 1998, pp. 20-45.

*33-y: holod: Narodna Knyha-Memorial* (The 33rd: Famine: A People’s Memorial Book) / Comp. L. B. Kovalenko, V. A. Manyak. – Kyiv: Rad. pysmennyk, 1991. – pp. 206–207.

[Memoirs] // *Dzvin*, 1993, Nos. 7, 8, 9.

“Cossack Kulish.” // *Zorya*. — May 17, 1997.

*Memoirs of a Pilot of the Dnieper Rapids*. – Dnipropetrovsk: Sich, 1998, 159 pp.; 2nd ed., with a foreword: Dnipropetrovsk: Polihrafist, 2000, 184 pp.

“A Museum… Perhaps the Only One in the World.” // *Dzherelo*. – November 27, 1998, p. 8.

*Dnieper Knights*. – Dnipropetrovsk: Polihrafist, 2000, 184 pp.

“The Steppes of Ukraine. The Spring Steppe of Our Region: Poetic Essays.” // *Sicheslavshchyna: A Regional Almanac*. Issue 4. – Dnipropetrovsk: DOUNB, 2002, pp. 52-60.

“Treasures of the Dnieper Steppe.” / Ed. H. K. Shvydko. – Dnipropetrovsk, 2002, pp. 61-62; Also: http://www.libr.dp.ua/region/Sicheslav_4.htm .

2.

Chaban, M. “The Rapids Obeyed the Pilot.” // *Zorya*. – January 23, 1991.

Anatoliichuk, P. “A Word About the Knight, Forged in the Waves of the Dnieper Rapids.” // *Borysfen*. – 1995, No. 4, pp. 16-17.

“A Worthy Great-Grandson of Glorious Forefathers.” // *Dneprov. panorama*. — January 23, 1996.

Kvitka, B. “Living History.” // *Prydneprov. mahistral*. — November 17, 1996.

Matyushchenko, B. “A Pilot—and That Says It All.” // *Dneprov. panorama*. — August 20, 1997.

“To Hryhoriy Mykytovych for Knowledge.” // *Dneprov. pravda*. — July 24, 1998.

Kalynova, D. “The Living Glory of the Pilots.” // *Nashe misto*. — June 24, 1998.

Krynychny, O. “A Good Conversation, and Worthy Honors.” // *Dzherelo*. — November 27, 1998.

Vasylenko, V.O. [Review of the book] Hryhoriy Omelchenko. *Memoirs of a Pilot of the Dnieper Rapids*. – Dnipropetrovsk: Sich, 1998. 159 pp. // *Southern Ukraine in the 18th-19th Centuries: Notes of the Research Laboratory of the History of Southern Ukraine, ZDU*. Issue 4 (5). – Zaporizhzhia: RA “Tandem-I,” 1999. – p. 275.

Shvydko, H.K. “The Last Pilot – A Literary Prize Laureate.” // *Southern Ukraine in the 18th-19th Centuries: Notes of the Research Laboratory of the History of Southern Ukraine, ZDU*. Issue 4. – Zaporizhzhia: RA “Tandem-I,” 1999. – pp. 296–297.

Zobenko, O. “Like a Sip of Living Water.” // *Zorya*. — December 29, 1999.

Sobol, Volodymyr. “The Legendary Pilot.” // *Dzherelo*. — January 14, 2000.

Dovhalyuk, Serhiy. “The Dnieper Rapids.” // *Ukrayina moloda*, 2000. – July 27.

“The Dnieper Pilot Crosses the Ocean.” // *Borysten*. – 2000, No. 9, p. 8.

KHPG Archive: Interview with H. Omelchenko on April 5, 2001.

Zobenko, A. “Living Witnesses to a Glory That ‘Will Not Die, Will Not Perish...’” // *Dniepr vecherniy*. – October 15, 2001.

Chaban, M. “The Soul Has Flown Beyond the Rapids. [Obituary].” // *Sicheslavshchyna: A Regional Almanac*. – Issue 4. – Dnipropetrovsk: DOUNB, 2002. – pp. 61-62; The same: Dnipropetrovsk Regional Universal Library, http://www.libr.dp.ua/region/Sicheslav_4.htm

Popovsky, Anatoliy. “Hryhoriy Omelchenko. An Essay on His Life and Work…” http://www.irp.dp.ua

Vasyl Ovsiyenko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. May 11, 2008.

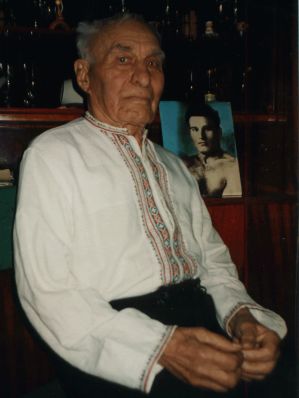

Hryhoriy Omelchenko with a portrait of himself from his student days. Photo by V. Ovsiyenko, April 5, 2001.