TRINCHUK, YAROSLAV IVANOVYCH (b. March 17, 1940, in the village of Stari Bohorodchany, Bohorodchany Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast).

Writer. Son of an insurgent. He did not renounce his father and was persecuted for it.

From a noble, hardworking, and prosperous family. His father, Ivan Mykolaiovych (b. 1912), directed the church choir. He was mobilized into the Polish army in 1939 and served in the cavalry. He saw his first battle when their cavalry charged German tanks. He suffered a concussion.

To protect his family and Ukraine, his father left his three children and joined the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army). He was killed by grenades in a bunker in 1945, when he was 33 years old and his son Yaroslav was 5. His father’s brother Vasyl died in an NKVD prison in 1939; his 25-year-old uncle Bohdan, an insurgent, was killed by NKVD agents in 1944 (Captain Belyayev shot him in the face). Relatives on his mother’s side, Kateryna Petrivna (1913-1980), also perished.

The family was destined for deportation to Siberia, but the mother went into hiding, and the infirm grandmother and the children alone were not taken. When the authorities took the land right up to her windows, the mother, to save her children from starvation, applied to join the collective farm, being the last one to do so in Stari Bohorodchany.

Yaroslav endured great hardship during the famine of 1947. They ate all the goosefoot and nettles around the village, but what he feared most was that his mother would take her own life. And such cases were not uncommon in the village.

From a young age, Yaroslav understood that the Soviet government was hostile; it wanted to destroy his family, to take their bread, land, and home. Incidentally, the family had nowhere to live, crowded into a tiny hut. They hoped to build a house from the barn. But the barn was taken away.

With great difficulty, he obtained a secondary education certificate. Starting from the eighth grade, he studied in evening schools in Bohorodchany, Odesa, and Ekibastuz, finishing the tenth grade in 1965 in Dnipropetrovsk.

In 1958, at the age of 18, Yaroslav beat up the secretary of the Komsomol district committee on the dance floor because he was harassing him. This trivial incident ruined his life. He was summoned by the secretary of the district party committee, who said, “We’ve been watching you for a long time.” He offered him a job and a career. “But you have to write a tiny little note—no one will even pay attention to it. We'll print it in small font at the end of the newspaper—that you renounce your father.” – “I will not renounce my father.” – “Well, write that your father was mistaken.” – “My father was not mistaken.” The young man became convinced once again that this state needed scoundrels. And he rebelled against it. That was the beginning of his thorny path. Just two months later, Yaroslav was in prison: in early 1959, a case of “embezzlement” was fabricated against him. At the time, he was a warehouse manager for containers, which had gotten wet and spoiled in the rain. They charged him 18,000 rubles, which he spent 20 years paying off. He was later told it was for not renouncing his father.

He served a six-month sentence in a general-regime camp in the village of Tovmachyk, Kolomyia Raion. Surprisingly, Trinchuk met many decent, intelligent people in captivity.

Afterward, he looked for work. In 1961, he worked in Odesa, building a railway. At that time, flour was being shipped from Odesa to Cuba (while there was no bread in the USSR). The sailors went on strike. Several men, including Trinchuk, spoke out in support of the dockworkers. They were rounded up and sent to Kazakhstan, to Ekibastuz. There, Trinchuk worked on the “constructions of socialism.” Specifically, in the “Irtyshuglestroy” trust, on the construction of a technological complex. He met former insurgents who had served 20-25 years. He was amazed (and still is) at how they managed to preserve their human dignity and honor in those conditions. They were wonderful people. But they were not allowed to return to Ukraine. This is described in his novella “The Exiles” (in the book *To Each His Own*). It is a small sketch from his incredible Kazakh adventures. A major who had once served in Western Ukraine worked at the military enlistment office in Ekibastuz, and he helped Trinchuk get documents that allowed him to come to Dnipropetrovsk.

He worked in construction. He finished the tenth grade in 1965. He was struck by the fact that the teachers respected and loved them, students with difficult characters.

He tried to get into university several times but could not pass the entrance competition. Only in 1971, at the age of 31, after many attempts, did Trinchuk, with the help of Professor Oleksandr Shylovsky, manage to enroll in the correspondence department of the philology faculty at Dnipropetrovsk State University. Later, Shylovsky met Trinchuk and scolded him with all sorts of words, saying, “Because of you, I’ve ruined my relations with such people!” However, the professor then warned the student to be careful.

Although Trinchuk was a good student (he has a diploma with honors), they did not let him have any hope of graduating. Just before his final exams, Trinchuk's “guardian,” KGB agent Volodymyr Semenovych Bondar, warned him that he would not pass Scientific Communism. “I don't want you to have a nervous breakdown later, but I must warn you that we cannot let you graduate from the university.” A fortunate accident helped. The chairman of the examination committee, Kost Petrovych Volynsky (who, by the way, thought Trinchuk's thesis was worthy of a candidate's dissertation), unexpectedly changed the exam schedule, and Trinchuk took the exam a day earlier than scheduled. A day or two later, a summons to the military commissariat arrived—this was how he was called to the KGB. As soon as he was led into the office, Bondar slammed his fist on the table and shouted, “You are a scoundrel, Trinchuk!” – “I know,” the graduate replied calmly. “You won’t have a job anyway!” – “I know that too.”

Trinchuk has three “Labor Books” completely filled with entries. Behind each entry is a detective story, a drama, a comedy.

While working in an evening school, the teacher became an object of close surveillance. Here is a typical situation. Trinchuk rephrases a stanza from V. SYMONENKO's poem “Where are you now, the executioners of my people?” He turns simple sentences into a complex one: “My people exist, my people will always be, no one will erase my people, all the turncoats and intruders will disappear, and the hordes of conqueror-vagabonds!” and dictates it to the students. The principal convenes a micro-pedagogical council. He takes a student’s notebook and shouts, “What is this sentence?” – “It’s a complex, compound, asyndetic sentence,” replies the teacher. “Do you have a different opinion?” – “What?! Are you mocking us?!” – The teacher takes out a collection published by the Central Committee of the LKSMU in 1981, opens it to page 65, demonstrating that he was expecting such a conversation, shows the poem to the principal and asks, “Do you have any complaints about the publisher?” When there was silence, he calmly said, “So you are the one trying to mock me.”

Somewhere he said that Dnipropetrovsk had over 150 schools, and only 8 of them were Ukrainian. He was fired from his job.

Provocateurs were sent to him, whom he wittily exposed by telling his own jokes and remembering who he told which joke to.

To prevent Trinchuk from engaging in pedagogical activities, a criminal “case” was fabricated against him in 1985. It was not completed in time: *perestroika* had already begun. But to avoid imprisonment, Trinchuk had to sign a pledge that he would not engage in anti-Soviet activities.

He was dismissed with a record of professional incompetence and sent to a factory as a carpenter. As soon as Trinchuk entered the human resources department, he was attacked for being a nationalist, and that all nationalists were bad. True, only women were there, and the candidate for the carpenter position turned the conversation into a joke, but he did not apply for the job.

In late 1985, he was hired as a dormitory warden at the river port. Sailors, longshoremen, crane operators—boys with character—lived there. They would have hired anyone for that position. When the head of human resources looked at his “Labor Book,” he said: “You’re just like them. To hell with you, I’ll take you. But write a letter of resignation immediately. The slightest thing, and you’re out without any fuss.”

The warden not only found common ground with the residents but also managed to get them to hide all the pornography from the walls in their closets, and to not shout during fights. The human resources department was delighted. But the Amur-Nizhnyodniprovsk district party committee found out that Trinchuk was working. They sent an inspection. The district committee instructor couldn't find any dirt in the dormitory and was furious. Suddenly, she glanced into one room, and a smile spread across her face. “Yaroslav Ivanovych, what is this Mother of God?! Do you let them hang icons?!” – “My dear Lyudmyla Hryhorivna, that's Raphael. Even every African knows that by now.” On the wall hung Raphael’s “Madonna” from the Hermitage. The party official flew into a rage and ran out. But he wasn’t fired for the “icon.” The river port management received reprimands for hiring a nationalist who had ordered a lecture on “Sex in the West” from the “Znannia” society. Their ingenuity was astounding.

True, he was dismissed according to the resignation letter he had written when he was hired. At his own request. Trinchuk then “lost” the “Labor Book” with the entry about professional incompetence and managed to get a duplicate issued. This way, he was later able to find a job in his profession.

There were not only dramas, but also comedies. During *perestroika*, Trinchuk was scolded by the entire pedagogical council for being the only one in the school who had not yet reformed. “I will not reform, because I was normal even before this,” he said at the council meeting. This offended the staff. Some stopped greeting him, and one of his former teachers still doesn't greet him to this day.

In October 1985, already during *perestroika*, guests came to Trinchuk’s place. A regular table setting. Vodka, snacks, toasts. Yaroslav raised a toast: “To an independent Ukraine!” The guests scattered. To justify themselves, they started a rumor: “Trinchuk is a provocateur!”

He took on all sorts of odd jobs… The most pleasant side job, he considers, was retyping the manuscripts of the writer Mykhailo Kulish, which have still not been published.

Trinchuk never had a stable job. Only in 1994 was he appointed director of the Dnipropetrovsk Regional Philharmonic. But to get rid of the independent director (who would invite an American conductor, then the pianist Ethella Chuprik from Lviv, and spoke exclusively in Ukrainian to everyone), the philharmonic was not allocated funds. They made it clear—he had to leave. June 7, 1995, is the last entry in his “Labor Book.”

He never had his own home either—he still lives with his father-in-law.

He managed to start a family at the age of 51. From his first wife, he has two daughters: Larysa (b. 1968), a computer science teacher, and Natalka (b. 1970), a doctor. With Olha Mykolaivna, he has a son, Danylo (b. 1992).

He retired in 2000.

All his conscious life, Trinchuk wrote, but “for the drawer.” Only after independence did he manage to publish some of his work.

In the late eighties and early nineties, he published the newspaper *Vilna Dumka* (Free Thought) and the magazine *Monastyrskyi Ostriv* (Monastery Island). Without support, he couldn't sustain them for long.

He was the head of the Sicheslav regional organization of the URP (Ukrainian Republican Party).

Bibliography:

1.

Trinchuk, Yaroslav. *Give Me Your Pains (The Hermits)*. A novel-impression. – Dnipropetrovsk: Porohy, 1992. – 178 pp. (The entire print run was sent to be recycled).

Trinchuk, Yaroslav. *To Each His Own*. – Ternopil, 1998. – 276 pp.

Trinchuk, Yaroslav. *Ave, Morituri!* (The entire print run was sent to be recycled).

Interview with Ya. Trinchuk, April 2, 2001. KHPG Archive.

Yaroslav Trinchuk. *To Each His Own*. (Novel. Full version). – Dnipropetrovsk, 2005.

Yaroslav Trinchuk. *Slaves of a Foreign Truth*. – Dnipropetrovsk, 2005.

Yaroslav Trinchuk. *Games Without Rules*. (Three novels). – Dnipropetrovsk, 2006.

Trinchuk, Yaroslav. *Man and Space*. A historical and cultural essay. www.ridnaukraina.com, March 5, 2007. Also on the same site – “There is not always an easy answer to a simple question.” A continuation of the essay – “Man and Space.”

Trinchuk, Yaroslav. *Man and Space*. – *Dzvin* journal, 2007. – No. 8.

Vasyl Ovsiyenko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, March 23, 2008. Corrections by Ya. Trinchuk added on April 11, 2008.

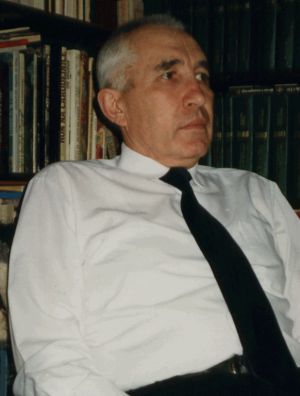

Yaroslav Trinchuk. Photo by V. Ovsiyenko, April 2, 2001.

Z