Bibliophile, organic chemist, and scholar. He printed *samizdat*, for which he paid with his academic career.

His father concealed from his sons that he had served in the army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR) and had been an émigré until the 1930s.

Myroslav finished school in Volodymyr, and in 1966, he enrolled at Odesa State University in the Faculty of Chemistry, from which he graduated in 1973 with a specialization in organic chemistry.

He worked as a schoolteacher for a year, then secured a position at the All-Union Breeding and Genetics Institute. He worked in the molecular biology laboratory, focusing on the electron microscopy of nucleic acids. This new field was well-funded, and the laboratory had excellent equipment. The prospect of preparing a dissertation opened up.

M. consistently spoke Ukrainian, which Odesans treated with tolerance. He loved books and collected them, particularly the series “Life of the Famous,” Ukrainian poetry, and books on the political history of Ukraine. He possessed books that had been removed from libraries and from sale. In the laboratory, he re-photographed books that were liable to be removed from circulation, notably S. Plachynda and A. Kolisnychenko’s “The Unburnt Bush” and V. Kubiyovych’s “Atlas of Ukraine and Adjoining Lands.”

Through this shared interest, in 1973, M. became acquainted with Vasyl BARLADIANU. The acquaintance blossomed into a friendship. Through him, M. had access to *samizdat* literature, in particular, he read the books of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

At BARLADIANU’s request, he would type his article “Such Is the Soviet Court,” and later other articles, on a typewriter in the laboratory in the evenings. Sometimes, BARLADIANU would type himself.

While on business trips to Kyiv, he would visit Maria OVDIYENKO and her husband, Dmytro Obukhov. From that time on, he noticed he was under surveillance. Accustomed to the open and free communication in the laboratory, M. paid it no mind. At work, he enjoyed trust and respect. However, on one occasion, without his superior’s permission, he and his colleagues used a program to calculate experimental results—this was a breach of procedure.

On June 16, 1976, KGB agents conducted a search of BARLADIANU’s home, confiscating a number of typescripts, including some typed on the typewriter from the laboratory where M. worked. The victim warned M. of possible trouble.

In the late autumn of 1976, M. received a phone call inviting him to stop by the institute’s personnel department after work to sign a document. He went, but near the institute building, a man asked, “You’re not Mosiuk, by chance?” “Yes.” And before he knew it, he found himself in a Volga, wedged between two KGB agents.

The interrogation, which involved “the one and only” General Kuvarzin, head of the regional KGB directorate, lasted until midnight. For several weeks, investigator Ivan Oleksandrovych Zadorozhnyi (or Zavgorodnii?) summoned him after work—to the KGB on Bebelya Street, to the prosecutor’s office, to a special room in the “Chorne More” hotel. He demanded a confession for printing *samizdat*, threatened criminal charges for producing anti-Soviet documents, and pressured him to collaborate with the KGB. M. tried to argue about freedom of speech, that the content of the articles he typed was not anti-Soviet but merely critical of the existing system. But he had to admit that he did, in fact, type them, as all typewriters were registered at the time, and the KGB had a sample from each one. Despite the demand to keep the interrogations secret, M. immediately told BARLADIANU about them. BARLADIANU said, “If it comes to that, say I came to you in the evenings and typed myself.”

At work, colleagues confessed that they had been summoned for questioning. Until then, everyone in the laboratory had expressed their views calmly and openly; there was a democratic atmosphere. Now, a sense of alienation arose. It felt as if he had to hide a terrible illness. He had the impression of being caught in the flywheel of a system that had broken his spine, trampled and defiled a person.

At the trial on June 27–29, 1977, M. had to act as a witness for the prosecution—there were no witnesses for the defense in a Soviet court. However, when the judge demanded an ideological assessment of his actions, M. replied: “If you think I’m saying something wrong, I can go sit on that bench, next to the defendant.” After being questioned, he was escorted from the courtroom.

The court issued a “separate ruling” regarding M. and sent it to his place of work. The director of the institute, Academician Oleksiy Sozinov, had a confidential, and generally proper, conversation with M. But he had to “react”: he allowed M. to continue his scientific topic but transferred him to the genetics department. However, it became clear that there was no longer any prospect of defending his dissertation, he was not sent on research fellowships to larger scientific centers to improve his qualifications, and his salary was paltry. All this deepened the conflict in his family, which led to a divorce. With several bundles of books, M. moved into a dormitory for graduate students, where he lived without official registration, moving from place to place.

At work, he felt a vacuum around him. Realizing that his intellectual career was over and that there was nothing left for him at the institute, M. moved to a radial drilling machine factory in January 1979. It was impossible for a person with a higher education to get a blue-collar job, so he had to use his new family’s connections. He worked in the scientific and technical information department, then as a foreman in the foundry, for a total of 15 years.

One day in 1980, he was summoned to the party committee, with which M. had no affiliation. There, alongside the party secretary, was his former investigator, now a lieutenant colonel. The KGB was fabricating a new case against BARLADIANU and needed “new materials,” which it intended to concoct with M.’s help. Here, the foundry worker felt his advantage and rebuffed him: “Well, if that’s the case, then issue me a travel order and pay for it. Because I work during the day, and then I rest.” They left him alone.

He continued to be interested in literature. He started a new family.

During the “perestroika” era, he attended rallies but did not join any civic or political organizations. However, as an observer, he took an active part in the 1990 referendum on the Union Treaty. He served as a member of a local election commission during the 2004 presidential election and participated in protests against the installation of a monument to Catherine II in 2007. In his circle, he champions pro-independence views. He is pleased that there is a Ukrainian state, to the emergence of which he also contributed.

Since 1995, he has been a leading specialist in laboratory equipment at the “Ekotekhnika” science and technology center. Since 200..., he has been retired.

Bibliography:

Interview with M. Mosiuk in Odesa, February 10, 2001.

Corrections by M. Mosiuk from April 7, 2008, entered on April 11, 2008.

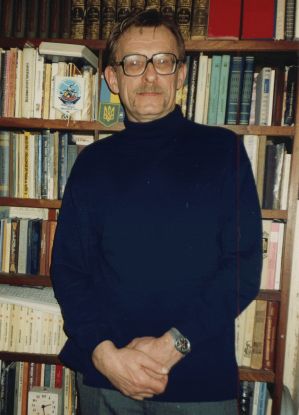

MOSIUK MYROSLAV MYKHAJLOVYCH