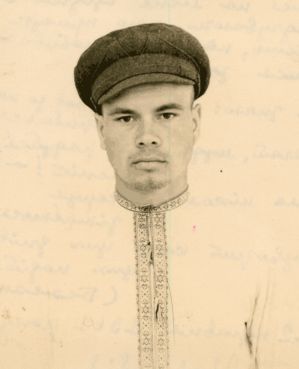

HRYHORENKO, OLEKSANDR YAVTUKHOVYCH (born February 22, 1938, in the village of Borodayivka, Verkhniodniprovsk Raion, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast – died August 19, 1962, buried in the village of Borodayivka).

A poet of the Sixtiers generation.

His father, Yavtukh Antonovych Hryhorenko, a collective farm chairman, along with his brigade leaders and accountant, was sentenced to death in 1932 for “squandering grain” because they had distributed grain to peasants for their workdays. A few months later, he was transported to the Far East. He was released in 1937. Meanwhile, his first wife died of starvation, while their daughter Nadiya and son Hryhoriy miraculously survived.

His mother, Yevdokia Sydorivna (maiden name Honchar, by her first husband Bondar), was born on March 14, 1905, in the Cherkasy region, in the village of Veremiyivka, Chornobai Raion. She was imprisoned in 1932 for 5 years for “counter-revolutionary activities”—in reality, for being the daughter of a “kulak.” At home, she left behind two young boys, aged 5 and 7. In the Kremenchuk prison where she was held, inmates went without food for weeks. The transport to Vladivostok lasted 20 days. In response to her numerous letters, news came from her native land: “Do not grieve and do not weep, Yavdoshka, for the Lord has taken your little ones, and not only yours, but many children and adults, half the village is gone. And your husband, Ivan, has also given his soul to God in Arkhangelsk, so his friend wrote, and in your house lives Yukhym the drunkard, and your garden is overgrown with weeds, and the orchard too is perishing. With that, be well and happy, but do not return home, for they will imprison you again.” After reading this, Yevdokia attempted to take her own life, but people saved her from sin.

Yavtukh and Yevdokia met in the Far East. In 1937, they returned to Borodayivka, and Yevdokia became a mother to her husband’s children and gave birth to a son, Sashko. His father was conscripted into the active army in 1941, was captured by the Germans in Kakhovka in 1943, and after his release in January 1946, was imprisoned again in a Soviet concentration camp. He wrote memoirs about this.

Sashko graduated from the Verkhniodniprovsk secondary school in 1956. From a young age, he wrote poetry but wanted to be in the military. He enrolled in the Vasylkiv Air Technical School near Kyiv, but after a few months, he submitted a resignation report: his innately intellectual nature could not accept the military drill, barrack-room monotony, and the foreign-language environment repelled him. In March 1957, he returned to his parents’ house. He intended to enter the Kyiv University Faculty of Language and Literature. But the local military commissariat drafted him for active duty. He served in the city of Qusar in Azerbaijan.

He wrote poems easily and simply, filled with dreams of love, love for his mother, for Ukraine, for his friends. He sent some to Kyiv magazines and to his classmates. Notably, he wrote a poem about the occupation of Hungary in 1956, which included the line: “Imre Nagy raises the flag!”

It is probable that a dispatch was sent after H. from the military school, ordering that he be monitored. His patriotically tinged poems fell into the hands of the KGB. He was arrested on October 2, 1958, and sentenced on January 16-17, 1959, by the Military Tribunal of the Baku District under Article 72, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the Azerbaijan SSR (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”) to 6 years of imprisonment. His parents wrote a letter to Khrushchev. On August 2, 1960, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR reduced his sentence to 3 years.

He served his sentence in a strict-regime camp of the “Dubravlag” administration, ZHKh-385/11, in the settlement of Yavas, Mordovia. The Mordovian camps during the “Khrushchev Thaw” were unique islands of freedom. Here, H. met many Ukrainians who also lived and breathed love for Ukraine, for its history and culture, and he communicated with interest with prisoners of other nationalities. Being an optimist, naturally cheerful, he found life in the camp easier and more interesting than in the army. He studied English, German, and French, and spoke Polish decently. He was friends with, among others, an Odesan, also a poet, Oleksa Riznykiv, with whom he practiced yoga. He wrote to him:

But do not forget that in gloomy days

Fate brought us together, so that we

In our literature, would be,

Above all—honest people!

He was friends with Mykola Kucher from Kamianske (Dniprodzerzhynsk). They—Riznykiv and Kucher—preserved the bright memory of the talented young man, his poems, in particular, they remembered the poem “To a Desired Bride,” written in 1961:

You will love me not for a song,

You will love me not for my looks—

You will love me for the iron

Devotion to the Ukrainian people.

H. was released on October 1, 1961. He returned to his native Borodayivka. He wrote poems and three prose pieces: “The Return,” “A Journey into Youth,” and “Spring Desires.” He worked on the construction of a combine plant and was planning to enroll in the philology department of Kyiv University. He corresponded with the poets Mykola Hirnyk and Mykola Som, and with the literary critic Viktor Ivanysenko, in particular about publishing a collection of his poems. He sent poems to Volodymyr P’yanov at *Literaturna Hazeta* (Literary Gazette), reproaching him: “Why am I not being published? Could the Mordovian ‘stains’ be the reason? Huh? That’s most likely… After all, I don’t write anti-state poems. Or maybe I should resort to hymns and odes? But no. I am too intelligent and honest to only offer praise, ‘as in the good old days.’”

H. responded to a selection of poems by a young poetess from the Vinnytsia region, Olena Zadvorna, which were published in May 1962 along with her portrait in *Literaturna Hazeta*. There were many responses to her poems, but the girl answered only him. She later wrote: “The first letter from Sashko with his poems made not just a pleasant impression, but also captivated with its special laconicism and clarity of thought. The poems were moving in their sincerity, emotionality, and artistic skill… Indeed, I secretly made my choice: yes, this is my young man, idealizing him for his spiritual, elegant, multidimensional word.” And she soon became convinced: “Sashko was a person of exceptional inner beauty, a strong-willed personality, always filled with spiritual balance and purposefulness.” A correspondence began that grew into a friendship. In July 1962, they met in Kyiv, where she had come to enter the university. But in September, she received, through a third party, a letter dated August 18, which Sashko had not had time to send. On the Feast of the Transfiguration, August 19, 1962, he went to the Dnipro River with his father and older brother. Other people were resting on the bank, and no one noticed where Sashko had gone. The search yielded nothing. Rumors spread through the village that he had hidden to escape abroad. KGB agents began interrogating people. But on the ninth day, his body surfaced downstream from the village. His mother identified him…

Several selections of H.'s poems have been published, along with memoirs about him. Oleksa Riznykiv and Olena Zadvorna-Halay are preparing a collection of O. Hryhorenko's works and memoirs for publication.

Bibliography:

І.

Oleksandr Hryhorenko. (Selection of poems). – *Vitryla* (Sails) (almanac). – 1967. – p. …

Oleksandr Hryhorenko. (Selection of poems) “Though we be cloudy”: To a Magician; Daydream; To a Friend; Depth of Soul. – magazine “Ukraina,” 12. – 1993. (Publication by Rostyslav Dotsenko)

Oleksandr Hryhorenko. (Selection of poems): You will love me not for a song; To a Friend; A Fleeting Moment; Today, having untangled the nets… – magazine “Vyzvolnyi Shliakh,” book 8 (617). 1999. – August. – p. 1006. (Publication by Halyna Hordasevych)

Oleksandr Hryhorenko. (Selection of poems). I want. To Mother. Daily. To Oleksa Riznykiv. To a Friend, Pavlo Felchenko. To a Fellow Prisoner // *Ukrainska Kultura*, No. 8 (970), August 2007. – p. 41. (Publication by Olena Zadvorna-Halay).

ІІ.

Mykola Kucher. Rise, Poet, Rise! // newspaper “Prydniprovskyi Komunar,” Verkhniodniprovsk, Nos. 5, 9, 10, 11. – 1993. – January 21, February 6, 9, 10, 11.

Rostyslav Dotsenko. “Especially Dangerous,” Thus Doomed to Obscurity. – magazine “Ukraina,” 12. – 1993. (Also includes a selection of poems “Though we be cloudy”)

Mykola Kucher. *Dubravlag. Spohady, opovidannia* (Dubravlag. Memoirs, Stories). – Dnipropetrovsk: VPOP “Dnipro,” 1996. – pp. 31-38.

Anatoliy Vorflyk. “So that after death, like a full sea, to pour into someone’s feelings.” – newspaper “Zhovtovodski Visti,” No. 17 (640), 1997. – April 25.

Halyna Hordasevych. You Will Love Me – magazine “Vyzvolnyi Shliakh,” book (617). 1999. – August. – pp. 1004–1006.

Interview with Oleksa Riznykiv by KHPG, March 25, 2000.

O. Riznykiv's Archive: notebook of poems by Oleksandr Hryhorenko.

Olena Zadvorna-Halay. A Bride’s Memoirs // *Ukrainska Kultura*, No. 8 (617), August 2007. – pp. 38–41. (Also includes a selection of six poems).

Archive of Olena Zadvorna-Halay.

Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Vasyl Ovsiyenko. Last read on December 21, 2007. Photos: 1956 at the Vasylkiv Military School; May 22, 1961, in captivity in Mordovia.