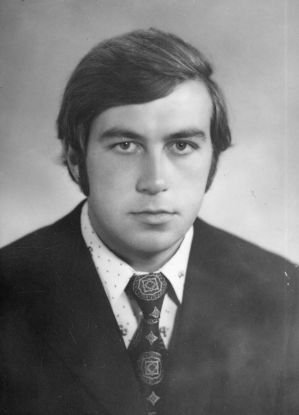

MYKYTKO, YAROMYR OLEKSIIOVYCH (b. March 12, 1953, in Prokofyevsk, Kemerovo region, Russia).

A founding member of the youth organization “Ukrainian National Liberation Front.”

Mykytko’s mother, Volodymyra Yurtsan, and father, Oleksiy Mykytko, met and married in exile in Siberia.

His maternal grandfather, Ivan Yurtsan, a former Sich Rifleman, organized the reburial of victims of the Soviet occupation in the town of Zolochiv after the Soviet army’s retreat in 1941. He was imprisoned in 1944, and his family was exiled to Siberia. His paternal grandfather, Hryhoriy Mykytka, was elected viyt (village head) of Ostriv, near the town of Shchyrets in the Pustomyty district of the Lviv region, during the German occupation and was also imprisoned for 10 years under Soviet rule. Mykytko’s father was a UPA courier but was exiled to Siberia as a family member of a repressed person.

In 1956, Mykytko’s parents returned to Ukraine and settled in the town of Shchyrets, later moving to Sambir.

Mykytko attended Sambir School No. 1 and, from 1967, School No. 10. He studied and was friends with Zoryan POPADIUK, who had a shortwave radio receiver, and together they listened to Radio Liberty. As 9th graders, they were outraged by the 1968 occupation of Czechoslovakia. Along with classmates Hennadiy Pohorielov, Oleksandr Ivantso, Emil Bohush, and Ihor Vovk, they wrote and typed a leaflet, boarded a bus to Ivano-Frankivsk, and posted it at every stop. Criminal cases were opened in the Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk regions, but the perpetrators were not found. After this action, the young men (Mykytko, Z. POPADIUK, E. Bohush, I. Vovk, O. Ivantso, Volodymyr Halko, Ihor Kovalchuk, Dmytro Petryna, and Yevhen Senkiv) gathered in POPADIUK’s yard and decided to create the “Ukrainian National Liberation Front” (modeled after the UNF, whose members had been arrested in 1967). They made a flag and a seal, established membership dues, purchased a typewriter, and reproduced samvydav literature. Works circulating in their circle included I. DZIUBA’s “Internationalism or Russification?,” photocopied articles by V. CHORNOVIL, and works by V. MOROZ. They also distributed leaflets in connection with the self-immolation of Czech student Jan Palach in Prague in protest against the occupation of Czechoslovakia.

After graduating from school in 1970, the young men dispersed to various cities (Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Rivne, Chernivtsi) and enrolled in universities, where they found like-minded individuals. Mykytko entered the Lviv Forestry Institute in the Faculty of Mechanical and Technological Woodworking, from which he was expelled on March 27, 1973, in connection with his arrest.

The organizational work of the UNLF was primarily led by Z. POPADIUK. His circle grew to several dozen people and even included children of the nomenklatura and “loyal Leninists,” such as the son of writer Ivan Svarnyk, who wrote secret reviews for the KGB on the works of I. KALYNETS, V. CHORNOVIL, and M. OSADCHY.

From their own and samvydav materials, in November–December 1972, the UNLF published the first issue of the typewritten journal “Postup” (Progress), with a foreword by Lviv University student Hryhoriy Khvostenko. The journal was printed in Sambir with a print run of one set of carbon copies, meaning 5 copies, and was 58 pages long.

In 1973, for the first time since 1939, Shevchenko evenings were banned in Lviv. In response, members of the UNLF printed 150 copies of a leaflet ending with the words: “Arise, and break your chains!” and distributed them in Lviv. Mykytko posted about 40 leaflets around the city on the evening of March 26. Fifteen minutes after returning to his apartment, he was detained by plainclothes KGB officers (investigator Vadym Ruzhynsky). Nothing was found during the search. Two or three leaflets remained in his jacket in the hallway, as Mykytko had put on a coat.

The first interrogation lasted almost a full day, from 3:30 a.m. until midnight. Mykytko gave no testimony. On the third day, as the investigation had evidence and testimony from other detainees (there were 10-12 of them), Mykytko confirmed their statements. The head of the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR, V. Fedorchuk, himself came to see the young “anti-Soviets.” The investigation was conducted against Mykytko, Z. POPADIUK, and H. Khvostenko, but the latter’s case was separated, ostensibly due to his illness, and he was not tried. Dozens of other students were expelled from their universities before the trial, and the young men were conscripted into the army. Lviv’s universities, especially the university, suffered a real purge, and many instructors were fired.

On August 13, 1973, at the Lviv Regional Court, the regional prosecutor Antonenko, wearing an embroidered shirt but speaking in Russian, demanded the maximum sentence for Z. POPADIUK and Mykytko under Article 62, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”). However, the court sentenced Mykytko to 5 years of imprisonment in strict-regime camps, while Z. POPADIUK received 7 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile.

Imprisonment became a good school for Mykytko: at Kholodna Hora prison in Kharkiv, he met the writer Vasyl Zakharchenko. In camp ZhKh-385/17 (Mordovia), he communicated with UNF leader Dmytro KVETSKO, Viacheslav CHORNOVIL, and young Lithuanians, Armenians, and Russians. He sewed work gloves. He participated in hunger strikes, for which he was transferred in the autumn of 1974 to zone 19, where his circle of contacts was even wider: insurgents Dmytro Syniak, Mykhailo Zhurakivsky, Ivan Myron, Mykola Konchakivsky, Roman Semeniuk, and “anti-Soviets” Ihor KRAVTSIV, Kuzma MATVIIUK, Vasyl OVSIENKO, and others. He worked at a woodworking enterprise.

In the autumn of 1976, Mykytko was transported to the Urals with a large group of prisoners. In zone VS-389/37 (Vsekhsvyatskaya station, Perm region), he installed machine tools. He met the leader of the Rosokha group, Volodymyr MARMUS. He served his final year in camp No. 35 (Polovynka village), where he communicated with Ivan SVITLYCHNY, Yevhen SVERSTIUK, Ihor KALYNETS, Valeriy MARCHENKO, Mykola HORBAL, Yevhen PRONIUK, Vasyl SHOVKOVY, Semen HLUZMAN, and Father Stepan Mamchur. He met his grandmother’s brother, Yevhen Pryshliak, who had served a 25-year sentence. From 1949-52, Pryshliak had led the Security Service of the OUN in the Lviv region, was arrested while wounded, and spent over 10 years in a solitary confinement cell in Vladimir Central Prison.

Mykytko was one of the authors and copyists of the “Chronicle of the ‘Gulag Archipelago.’ Zone 35.” He managed to smuggle out a part of it upon his release, even though the transport journey lasted a month and a half. In particular, it recorded that on August 6, 1977, Mykytko’s statement regarding the then-discussed draft of the USSR Constitution was confiscated. On October 2, he, along with others, declared a “week of silence.” Since the prisoners did not respond verbally during roll call but only raised their hands, the officer on duty, Chaika, “did not notice” them and reported them as absent. On October 8, he protested against forced labor. On the Day of the Soviet Political Prisoner, October 30, he signed a telegram to the Belgrade CSCE conference. On November 15, Mykytko was deprived of his right to receive a parcel, and on December 28, he was thrown into a punishment cell.

Mykytko was released in Lviv on March 27, 1978. He was under administrative surveillance for six months.

In 1979, Mykytko married Tetiana Shvets. They have a daughter, Iryna (b. 1980), a son, Oleksa (b. 1983), and a grandson, Danylo Yamelynets (b. 2003).

In 1982, Mykytko re-enrolled in the Lviv Forestry Institute, in the correspondence department of forestry. He worked in forestry enterprises as a woodcarver, warehouse manager, and foreman. When Z. POPADIUK came on leave from exile in 1980, Mykytko, who was financially responsible for the warehouse, was sent for military retraining. However, they still managed to meet.

From 1990-94, Mykytko worked as an adviser to the mayor of Sambir, Z. POPADIUK, and was the editor of the newspaper “Visnyk miskraiderzhadministratsiyi” (Herald of the City and District State Administration). Since 1994, he has worked as an instructor in the organizational department, then as secretary of the commission on social protection for Chornobyl victims, and secretary of the environmental safety commission of the Sambir district. He later became a chief specialist in the department of labor and social protection of the Sambir District State Administration.

Bibliography:

I.

Interview with Yaromyr Mykytko on January 27 and 30, 2000. https://museum.khpg.org/1185644292

II.

Alekseeva, Lyudmila. Istoriya inakomysliya v SSSR. Noveishiy period (The History of Dissent in the USSR. The Newest Period). – Vest. Vilnius – Moscow (VIMO), 1992 (first ed. 1984). – 11.

Mykola Horbal. “Vaha slova. ‘Khronika “Arkhipelaga GULAG”. Zona 35 (Za 1977 r.)’” (“The Weight of a Word. ‘Chronicle of the ‘Gulag Archipelago.’ Zone 35 (For 1977)’”) // “Zona” magazine. – No. 4, 1993. – pp. 134–150.

Kasianov, Heorhiy. Nezhodni: ukrainska intelihentsiia v rusi oporu 1960-80-kh rokiv (Dissenters: The Ukrainian Intelligentsia in the 1960s-80s Resistance Movement). – Kyiv: Lybid, 1995. – pp. 135–136, 142.

Lviv. Istorychni narysy (Lviv. Historical Essays). Comp. Ya. Isayevych, F. Stebliy, M. Lytvyn. Institute of Ukrainian Studies. – Lviv, 1996. – pp. 543–610.

Anatoliy Rusnachenko. Natsionalno-vyzvolnyi rukh v Ukraini (The National Liberation Movement in Ukraine). – Kyiv: O. Teliha Publishing. – 1998. – pp. 196–206.

International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents from Central and Eastern Europe and the Former USSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny,” 2006. – pp. 474–477. https://museum.khpg.org/1184408272

Rukh oporu v Ukraini: 1960–1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk (The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960–1990. An Encyclopedic Guide) / Foreword by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. – Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010. – p. 435; 2nd ed.: 2012, – pp. 487–488.

Vasyl Ovsiienko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. March 19, 2004. With corrections by Y. Mykytko. Last read on August 12, 2016.