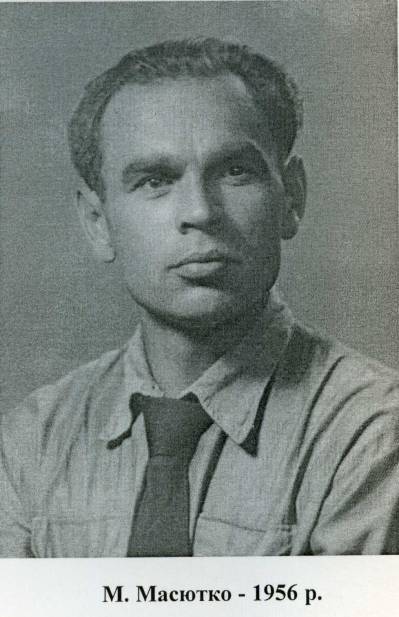

MASIUTKO, MYKHAILO SAVYCH (b. November 18, 1918, in the village of Chaplynka, Kherson region – d. November 18, 2001, in Lutsk).

Teacher, writer, publicist.

From a family of teachers. He survived two famines and the dekulakization of his fellow villagers. In 1932, his father was transferred to the town of Oleshky. In 1933, Masiutko finished seven years of school in Tsiurupynsk and entered the rabfak (workers' faculty) at the Kherson Pedagogical Institute, while his parents moved to Crimea. From 1934, he studied at the Faculty of Language and Literature at the Zaporizhzhia Pedagogical Institute. In 1936, he was expelled from the Komsomol and from his third year of study based on a denunciation: at a party, students had spoken about the famine of 1933. A friend helped Masiutko get a job as a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature in the village of Kraievshchyna, Volodar-Volynskyi district, Zhytomyr region.

In 1937, Masiutko went to Kyiv to buy clothes and was arrested on a slanderous denunciation that he had allegedly engaged in counter-revolutionary propaganda at the train station. On November 17, he was sentenced to 5 years of imprisonment and 3 years of disenfranchisement. He served his sentence in Kolyma, working in gold mines under extremely harsh conditions. He frostbit the toes on his right foot and injured his knee. After defending a Latvian man who was being beaten by a brigade leader, he himself was tortured. His prayers may have saved him: his mother managed to get his case reviewed. On November 3, 1939, the Supreme Court of the USSR overturned Masiutko's sentence and closed the case due to insufficient evidence. He was released and rehabilitated but was not allowed to leave Kolyma. He later taught German in a school in the Srednekansky district of the Khabarovsk Krai.

Meanwhile, in 1939, his brother Serhiy was imprisoned for 6 years, and in 1940, his father died in Crimea.

In 1942, Masiutko was conscripted into the army and sent to the front. In 1946, he was demobilized in Berlin. He was awarded a medal. After the war, he returned to his family in the village of Sarabuz in Crimea and worked as a teacher. To escape the famine, he and his mother moved to Galicia in 1946, where he worked as the head of studies at Railway School No. 10 in Drohobych.

In 1948, Masiutko enrolled in the editorial and publishing faculty of the Lviv Polygraphic Institute. He was an excellent student and took an active part in the institute's social and cultural life. At the end of 1952, he wrote a paper for a scientific circle titled “Norms of Communist Morality,” which was deemed ideologically flawed. He was expelled from the institute before defending his diploma thesis in 1953.

In 1949, Masiutko enrolled and in 1953 graduated externally from the philological faculty of the Lviv Pedagogical Institute with a degree in Ukrainian language and literature. He taught in Volyn, worked as a research fellow at the Ivan Franko Museum in Lviv. In 1962, he married a friend of Olena ANTONIV, Hanna Romanyshyn, who became his associate and reliable support for the rest of his life. He taught in the village of Oleksyn in the Lviv region, in Kivertsi in Volyn, and in the village of Staiky in the Kyiv region. In 1956, he defended his diploma thesis at the Moscow Correspondence Polygraphic Institute, specializing as an art editor for printed products. In 1957, he moved to his mother's home in Feodosia, taught drawing, drafting, and Ukrainian in a school and a technical college, and built a house.

He had been writing short stories, humorous pieces, and poems since the 1940s, but publishing them at that time was out of the question. After retiring from teaching, he focused on his literary work, writing articles, novellas, and short stories, some of which were published in the republican and regional press of Crimea and the Lviv region. He also worked as a graphic artist, designing books, mostly for the Lviv publishing house “Kamenyar.”

From the early 1960s, Masiutko was an active participant in the Sixtiers movement. He wrote a series of sharp publicist articles that were circulated in samvydav, namely: “Literature and Pseudo-literature in Ukraine,” “A Reply to Vasyl Symonenko's Mother, Hanna Fedorivna Shcherban,” “From the History of the Ukrainian People's Struggle for Their Liberation during the Civil War. From Materials Burned in Kyiv,” “Contemporary Imperialism,” “The Class and National Struggle at the Present Stage of Human Development,” as well as a number of short stories and poems.

In mid-August 1965, Mykhailo and Olha HORYN, Dmytro Pavlychko and his wife Bohdana, Ivan DRACH, and Roman Ivanychuk were all vacationing in Crimea at the same time. Masiutko organized a trip for them to the Kara-Dag mountains. They were almost openly followed by KGB agents. This outing would later be referred to in case files as a “summit meeting.”

On August 25, 1965, the arrests of the Sixtiers began. Masiutko was arrested on September 4 in Feodosia. The next day, he was flown to Lviv, where the investigation into the case of Masiutko, Mykhailo and Bohdan HORYN, M. OSADCHY, M. ZVARYCHEVSKA, and Y. MENKUSH was conducted.

During the search of Masiutko's home, about a dozen samvydav articles that he had recently brought from Lviv and had carelessly failed to hide were confiscated. In addition to the ones mentioned above, these included: “On the Occasion of the Trial of Pohruzalsky” (which Masiutko had edited), “Ukrainian Education in a Chauvinist Noose” (authored by M. HORYN), “The State and Tasks of the Ukrainian Liberation Movement” (authored by Y. PRONIUK), “A Letter to Iryna Vilde,” “12 Questions for Those Who Study Social Science,” “On the Present and Future of Ukraine,” Masiutko's note “The Goal of the Article Is Not That...” — a response to M. HORYN’s comments on the article “Contemporary Imperialism,” poems by V. SYMONENKO and L. KOSTENKO, an excerpt from V. Sosiura’s poem “Mazepa,” P. Kulish's novel “The Black Council,” works by M. Hrushevsky, and his own literary output: articles, poems, novellas, and short stories, which constituted an entire volume of the preliminary investigation materials. These included the satirical stories “The Revolutionary Grandfather,” “Blood Calls to Blood,” the novella “Chimera,” and others. Although his literary works were not widely circulated, the author was accused of having “produced and stored them with the intent of subsequent distribution,” and the investigation also used them for philological expert analyses.

During the investigation, Masiutko borrowed the works of V. Lenin from the library and wrote a piece about the deviations from “Leninist norms of national policy” in Ukraine, which he sent to the presidium of the 23rd Congress of the CPSU. He aptly used this same “enemy's weapon” for argumentation during the investigation and in court. Masiutko neither confirmed nor denied authorship of the articles, only arguing that there was no proof of his authorship and that they were not anti-Soviet because they were not directed against the Soviet government: the anonymous authors were criticizing chauvinism and communist ideology.

Given the large volume of the case and to minimize its publicity, Masiutko's case was separated from the group case into a separate proceeding. The head of the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR, V. Nikitchenko, himself spoke with him. Almost uniquely among all those arrested in the 1965 sweep, Masiutko did not testify against anyone, did not make excuses, and did not admit his guilt. (Masiutko later described the course of the investigation and trial in detail in his book “In Captivity of Evil”).

Regarding the articles confiscated from him, Masiutko claimed that he had bought them along with a typewriter in Halytska Square for 80 rubles. The prosecution based its accusations on the testimony of brothers B. and M. HORYN, who stated that they had received literature from him. This testimony was contradictory, so the KGB, perhaps for the first time, decided to use literary and philological expert analyses against Masiutko. Based on the results of these falsified analyses, he was attributed with the authorship or co-authorship of all the works confiscated from him. The experts were linguists and literary scholars from Lviv University: F. Neborachek, V. Y. Zdoroveha, S. M. Shakhovsky, and I. S. Hrytsiutenko. Masiutko thoroughly refuted their conclusions. A second commission was proposed, including I. Kovalyk and V. Shchurat from Lviv, Y. Shabliovsky and K. Volynsky from Kyiv, and Zozulia from Moscow, but they all declined under various pretexts. A new commission included M. F. Matviichuk, P. Leshchuk, M. Khudash, V. M. Kybalchych, B. Kobyliansky, and O. Babyshkin. They diligently fulfilled the KGB's order: by manipulating facts, they “established” that the author of the articles and literary works was characterized by the use of parallelism, antithesis, colons, aphorisms, rhetorical questions, exclamations, etc., and even gave an ideological characterization of the works, which was not required of them. The conclusions of the two expert reports were contradictory and provided no real evidence for the investigation, but this did not prevent the indictment from being built precisely on their results. In court, Masiutko left no stone unturned of the conclusions of the philologist-experts present, yet according to the court's verdict, he still had to pay the respected doctors and candidates of sciences 1,483 rubles and 50 kopecks. A third commission was formed in court from the experts present, which made similarly unconvincing conclusions.

When Masiutko was brought to trial on March 21, 1966, Olha Horyn shouted to him: “Mykhailo, you are a hero!” In the courthouse corridor, snowdrops were thrown at his feet (in particular, by student Lyudmyla Stohnota). His wife Hanna rushed to kiss him, and during a court recess, she broke into the courtroom and gave him tangerines. The guards were bewildered, and the prison warden himself had to intervene... However, the guards treated Masiutko with obvious sympathy. None of his relatives were allowed into the courtroom; only the shamed “experts” sat there.

In court, M. HORYN retracted his previous testimony, explaining that he had shown cowardice at the beginning of the investigation and had tried to protect himself. Only the confusing testimony of the sole witness, B. HORYN, remained. The lawyer, O. P. Serhiienko, avoided assessing the incriminated works and proposed that Masiutko be acquitted.

The court attributed authorship of only two documents to him (“Contemporary Imperialism,” where the USSR was characterized as a Russian communist empire, and “The Goal of the Article Is Not That...”) and participation in the writing of seven documents. On March 23, 1966, the verdict was announced: 3 years of prison confinement and 3 years in strict-regime camps on charges of conducting anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda (Part 1, Art. 62) and organizational activity (Art. 64). As Masiutko was being led from the court, Olha Horyn and others again strewed his path to the prison van with snowdrops.

On May 17, 1966, the Supreme Court partially satisfied Masiutko's appeal and fully satisfied the lawyer's appeal: it dropped the charges of authorship of some anonymous articles, the charge of organizational activity, the payment for the false expert reports, and replaced the prison confinement with strict-regime camps, leaving the 6-year term. But Masiutko did not escape prison...

A record of Masiutko's trial, his refutation of the expert reports, and his final statement soon appeared in samvydav. As an example of brazen falsification, V. CHORNOVIL meticulously examined Masiutko's case in his works “Justice or a Relapse into Terror?” (1966) and “The Trouble with Intellect” (1967), for which he himself paid with his freedom.

In the Mordovian strict-regime camp ZhKh-385/1, in the village of Sosnovka, despite his poor health (a duodenal ulcer and a complex cancer surgery under his heart 4 years earlier), Masiutko was forced to work as a loader for an emergency brigade. His post-operative stitches came apart. He was transferred to weaving “avoskas” (string bags). Masiutko wrote a “Statement to the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine,” for which he was placed in a punishment cell for 6 months in December 1966, accused of “producing and distributing anti-Soviet documents in the camp.” Through his Baltic friends, he managed to smuggle it out. It was this statement that the Ukrainian Helsinki Group quoted in its “Memorandum No. 1” in 1976:

“If any traveler, in defiance of all categorical prohibitions, were to visit the political prisoner camps in Mordovia, of which there are six, he would be extremely struck: here, thousands of kilometers from Ukraine, at every step he would hear the distinct Ukrainian language in all its contemporary dialects. The traveler would involuntarily ask: what is happening in Ukraine? Unrest? An uprising? What explains such a high percentage of Ukrainians among the political prisoners, which reaches up to 60, and even 70 percent? If such a traveler were to visit Ukraine shortly after, he would immediately be convinced that there is no uprising, no unrest in Ukraine. But then a new question would arise for him: why is the Ukrainian language heard so rarely in the cities of Ukraine, and why is it heard so frequently in the camps for political prisoners?”

Masiutko was transferred to camp ZhKh-385/17A, in the settlement of Ozerny (Umor), where, as a disabled person, he was assigned to pack gloves sewn by other prisoners. His friends there were the Lithuanian Balys GAJAUSKAS, the Jew Aleksandr GINZBURG, the insurgent V. PIDHORODETSKY, and the dissident M. KOTS.

On July 18, 1967, prisoners M. HORYN, Masiutko, and V. MOROZ were summoned one by one to the headquarters. It turned out to be for a session of the Zubovo-Polyansky District Court, which, without prior charges and without a defense lawyer, sentenced them to 3 years of prison regime in Vladimir Prison (V. MOROZ until the end of his term), allegedly for systematic failure to meet work quotas and for violating camp discipline. The conditions of detention there were particularly harsh. The first three months were a starvation quarantine: 300g of bread, a handful of rusty sprat, and a ladle of porridge, totaling 900 kcal. For the next two years, he was in the overcrowded cell No. 33, where his cellmates included S. KARAVANSKY, Volodymyr Bezuhly, M. LUTSYK, the Finn Villi Forsell, the Lithuanian Gindlis, the Armenian Oganesyan, the Kazakh Kulemagombetov, and others. It was cold there in winter, and there was always a lack of air. The daily ration was 1500 kcal, costing 9 rubles a month. However, the library of this prison contained a great deal of literature confiscated from the repressed intelligentsia. Masiutko refused to work and was kept on a reduced ration, which gave him time for intellectual work. He compiled a Ukrainian-Esperanto dictionary and wrote a publicistic story, “The Death of Stalin,” which, along with Z. KRASIVSKY’s poem “Freedom,” he managed to smuggle out through his wife. It was broadcast on Radio Liberty. Later, D. KVETSKO, I. KANDYBA, M. HORYN, L. LUKIANENKO, Mykola Tanashchuk, and others were brought to the cell. One day, a prisoner named Samyshkin found an earthworm in his gruel. All the cellmates declared a hunger strike. On the third day, the cell was disbanded.

In July 1970, Masiutko returned to camp No. 17A, from which he was released in September 1971.

He was not allowed to register his residence in his own house in Feodosia; it had to be sold, and he settled on a family homestead in the village of Dnipriany near Nova Kakhovka, without the right to travel and under the close surveillance of KGB agents. From time to time, KGB officers visited Masiutko, and he was summoned for interrogations about N. SVITLYCHNA, Z. POPADIUK, I. SOKULSKY, M. HORYN, and V. MOROZ, but they got nothing from him.

In early March 1977, Masiutko and his wife visited O. MESHKO in Kyiv, where he met L. LUKIANENKO, who was returning from an interrogation in the case of M. RUDENKO, which was being conducted in Donetsk. He agreed to become a member of the UHG but asked that his name not be announced until he had finished his memoirs: from October 6, 1973, to August 31, 1979, he secretly wrote the book “In Captivity of Evil.” Fearing a search, he had buried his manuscripts in the ground, where they lay for three years. He finished editing and rewriting the book on July 19, 1985. It was published in 1999 through the efforts of his brother, Vadym Cherkas-Masiutko.

During his last 30 years, Masiutko wrote most of his literary works. In the late 1980s and 90s, he appeared as a publicist in the press, on radio, and on television. In his last years, he was in poor health. At the age of 83, in September 2001, Masiutko had to leave his house in Dnipriany and move to his wife Hanna's relatives in Lutsk. "So, which prison are they taking us to now?" were his last words as he got into the cargo bus.

He was rehabilitated on October 28, 1992. He died on November 18, 2001, on his birthday. He was buried in Lutsk at the suburban cemetery “Harazdzha.” His wife Hanna died on May 24, 2006, and was buried next to him.

In 2003, his brother Vadym Cherkas also published a book of Masiutko's short stories. Awaiting publication are his poems, publicistic writings, and scholarly works: “Ivan Franko in the Fine Arts,” “Neologisms in the Work of Lesia Ukrainka,” “‘Pan Tadeusz’ in the Translation of Maksym Rylsky,” “Peculiarities of Maksym Rylsky's Translations,” and others.

Bibliography:

I.

M. Masiutko. “Zaiava do Verkhovnoi Rady Ukrainy” (“Statement to the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine”) // Ukrainska intelihentsiia pid sudom KHB (The Ukrainian Intelligentsia on Trial by the KGB). – Suchasnist, 1970.

M. Masiutko. “Vykhovannia ‘lastochkoiu’” (“Upbringing by the ‘Swallow’”) (1977). – Poklyk sumlinnia (Call of Conscience), No. 33 (141), 1993. – September.

Masiutko M.S. V poloni zla: Memuarna poema (In Captivity of Evil: A Memoir in Verse). – Lviv, 1999. – 608 p.

Masiutko M.S. Dosvitnii spolokh: Opovidannia (Pre-dawn Alarm: Short Stories) / Art. design by V. Cherkas. – Lviv: Kameniar, 2003. – 207 p.

Khymera (Chimera) / Yevrosvit, 2007. - 320 p.

II.

V. Chornovil. Lykho z rozumu (The Trouble with Intellect). Lviv: MEMORIAL, 1991. – pp. 183–214.

Kasianov, Heorhiy. Nezhodni: ukrainska intelihentsiia v rusi oporu 1960–1980-kh rokiv (Dissenters: The Ukrainian Intelligentsia in the 1960s–80s Resistance Movement). – Kyiv: Lybid, 1995. – pp. 29-31, 47-55.

Horyn M.M. Lysty z-za grat (Letters from Behind Bars). – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, Folio, 2005. ─ pp. 13, 26, 30, 58, 59, 149, 175, 254, 276.

Ukrainska Hromadska Hrupa spryiannia vykonanniu Helsinkskykh uhod: V 4 t. (The Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: In 4 vols.) / Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; Comp. V.V. Ovsiienko; – Kharkiv: Folio, 2001. – Vol. 2. – p. 37.

Interview with his wife, Hanna Hryhorivna. February 20, 2001. https://museum.khpg.org/1380835002

International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents from Central and Eastern Europe and the Former USSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 2. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny,” 2006. – pp. 446–452. https://museum.khpg.org/1184405441

Lukianenko L. “Mykhailo Masiutko” // Lukianenko L. Z chasiv nevoli (From the Times of Captivity). – Book 2 – Kyiv: MAUP, 2007 – pp. 261-264; Shliakh do vidrodzhennia: v 13 t. (Path to Revival: in 13 vols.) Vol. 6: Z chasiv nevoli: knyha druha (From the Times of Captivity: Book Two) / Levko Lukianenko – Kyiv, LLC “Yurka Liubchenka,” 2014. – pp. 261–264.

Horyn, Bohdan. Ne tilky pro sebe: Roman-kolazh: U 3 kn. (Not Only About Myself: A Collage Novel: In 3 books). – Book One (1955–1965). – Kyiv: Univ. Publishing PULSARY, 2006. – pp. 338–340; Book Two (1965–1985). – 2008. – pp. 23, 69, 83-86, 92-93, 95-96, 98, 101, 103-104, 106, 124, 127, 129-130, 135, 140, 147, 150-153, 162, 180, 274, 580-581, 584.

Rukh oporu v Ukraini: 1960–1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk (The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960–1990. An Encyclopedic Guide) / Foreword by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. – Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010. – pp. 417–419; 2nd ed.: 2012. – pp. 468–470.

Vasyl Ovsiienko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. June 5, 2006. Last read on August 12, 2016.