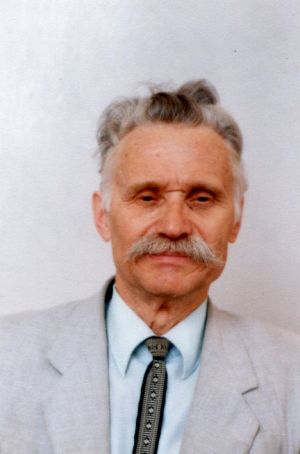

ANATOLIY KUZMOVYCH ZDOROVYI (born January 1, 1938, in the village of Tsapivka (now part of the urban-type settlement of Vapniarka), Tomashpil Raion, Vinnytsia Oblast).

A scientist who spoke out against Russification. A public and political figure.

His father, Kuzma Saveliyovych Zdorovyi, born in 1910 in the Kharkiv region, was of Cossack lineage and a military man. His mother, Yevdokia Saveliyivna Shvets, 1910–1990, was from the Vinnytsia region. Both came from families that had been “dekulakized” and dispossessed. Anatoliy’s great-uncle had served in Makhno’s army, received a death sentence that was commuted to 25 years, and served 18 years of his term.

During the war, the family tried to evacuate but was encircled in the village of Maryanivka, Tyshkivskyi Raion, Kirovohrad Oblast, where they settled. Anatoliy began school there. When his father returned from the war with Japan in 1946, the family settled in the village of Shliakhova in the Kharkiv region.

He finished school in 1955 and enrolled in the nuclear department of the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics at Kharkiv State University. He was a Komsomol activist, serving as deputy chief and later acting chief of the student construction brigade building the university’s new corpus. In 1957, as part of a student brigade, he traveled to the Virgin Lands in Kazakhstan, where he worked as a combine operator. In 1959, he was the deputy commander of the Kharkiv student brigade. He holds the medals “For the Development of Virgin Lands” and “For Courage” (for rescuing people from a burning bus).

His studies came easily to him, so Zdorovyi spent a lot of time on public affairs. He graduated from an evening music school, where he studied violin. He also attended individual courses at the faculties of philology and law. In 1959, during his fifth year, he was recommended for Party membership but did not join, as he was already concerned about the advance of Russification in general education and higher education schools.

In the autumn of 1960, after graduating, Zdorovyi was assigned to the magnetohydrodynamics laboratory at the Kharkiv Electromechanical Plant (KHEMZ), which studied physical processes in specific conditions (in space, at high temperatures, and in gravitational and high-frequency fields).

During his holidays and later on vacation, Zdorovyi went on ethnographic expeditions, organized flower-laying ceremonies at the monument to T. Shevchenko, and participated in publishing a wall newspaper at the institute, to which he gave a Ukrainian focus. He was a regular listener of Radio Liberty. Zdorovyi was first summoned to the KGB as a witness in 1959 in the case of Anatoliy Prostakov and Vasyl Myshutin, who were convicted of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.”

In 1964, Zdorovyi was assigned a position as a deputy of the district council. He was approached by parents of schoolchildren who complained that Ukrainian schools were being massively converted to Russian as the language of instruction. Zdorovyi collected the signatures of two hundred parents, raised the issue at the local level, and traveled to Kyiv and Moscow on the matter. Plainclothes “parents” began attending parent meetings, advising others to “understand the Party line correctly,” “not agitate the people,” and “be reasonable.” Soon, the number of protesting parents dropped to about fifteen. Then, on the evening of June 29, 1965, Zdorovyi wrote in large letters on the fence of the House of Projects under construction on Lenin Avenue, across from the Intourist Hotel, the slogan: “Ukrainians! Cherish your native language! Down with the vile theories of ‘natural assimilation’! Long live Ukraine!” He ran out of paint for the last letter and the exclamation mark. He went home, got a new can, and finished the job properly. Dawn was breaking. The few passersby who walked behind him were shooed away by policemen. The daring man calmly packed his paint and brush into a bag and headed home. A police patrol followed him. A car pulled up, and someone shouted, “Detain him!” Footsteps thundered. Zdorovyi also started running, but he was caught and taken to the Dzerzhynsky District Police Department. In the morning, he was moved to a pretrial detention cell at the UKGB. The protester considered his actions legal, aimed at defending the national policy proclaimed by the Party and government, and completely rejected the accusations of an anti-Soviet and anti-Party nature of his act.

After a 20-day arrest and interrogations, Zdorovyi was released with the appropriate official warnings. A likely factor was that he worked in a secret research laboratory for space exploration, which reported to Moscow’s P.O. Box 654, and he himself was the responsible executor of the project “Research on thermophysical processes in liquid metal coolants under conditions of weakened gravitational fields modulated by Ampere-Lorenz forces.” Academicians of the USSR Academy of Sciences M. D. Millionshchikov and V. P. Mishin, the director of the Institute for Low Temperature Physics and Engineering (ILTPE) of the Academy of Sciences of the UkrSSR, Academician B. Ye. Verkin, the deputy director for scientific work B. Yeselson, and the heads of the sector and laboratory R. S. Mikhalchenko and Yu. A. Kyrychenko all stood up for him. The Kharkiv KGB officers did not expect such unanimity and were probably unable to reach a common understanding with their Moscow colleagues. Furthermore, Zdorovyi’s biographical “service record” at the time was not just reliable but exceptionally positive from the standpoint of political attitudes. He submitted a lengthy explanation stating that he had no intention of “undermining the Soviet state and social order” but rather of improving it.

Before his release, Zdorovyi was summoned by the head of the Kharkiv KGB, General Petrov. He staged a reading of V. SYMONENKO’s poems but also treated the prisoner to water, after drinking which Zdorovyi could not concentrate his memory and his eyes teared up.

Zdorovyi’s act and the related events alarmed the local communist authorities, as a representative of the younger elite, educated and close to the Communist Party-Komsomol nomenklatura, had openly spoken out. Moreover, he was demonstratively supported by the scientific elite of Kharkiv and Moscow. The zeal of the local Russifiers temporarily subsided to a certain extent.

Zdorovyi was placed under close surveillance. Two years later, on May 30, 1967, at the request of the KGB, he was dismissed from his job “at his own request.” Of course, the defense of his dissertation, titled “Thermotechnical Studies of Liquid Metals in Zero-Gravity Conditions,” which was scheduled for August 30 at the ILTPE, was thwarted. By then, he was the author of 9 inventions and about 20 scientific papers.

Zdorovyi did not change his behavior, though he did focus more on scientific work at the Giprostal plant, where he prepared a new dissertation for the Candidate of Technical Sciences degree on the topic “Increasing the Durability of Steelmaking Converters by Cooling the Lining,” which he defended in 1971. The Higher Attestation Commission (VAK) approved it only in May 1972.

The preparation of his dissertation involved trips to other cities, and Zdorovyi’s circle of acquaintances and political interests expanded. He met I. DZIUBA and Oles Honchar and collected a Ukrainian library. The KGB periodically, every six months, conducted searches of his home, confiscating about 300 volumes, including books by M. Hrushevsky and V. Vynnychenko, pre-war Galician publications, some Soviet books that were being withdrawn from sale and libraries, a letter, poems, and photographs of Vasyl SYMONENKO, with whom Zdorovyi was acquainted, and draft letters to the Central Committee of the CPSU in which he laid out his views on economic problems.

For the 100th anniversary of Lesya Ukrainka’s birth, Zdorovyi, along with engineer Ihor Kravtsiv, raised the issue of creating a memorial room in Kharkiv, naming a street or square, and erecting a monument. Among the creative unions, only the regional branch of the Writers’ Union (headed by Ihor Muratov) dared to support them.

Meanwhile, the CPSU’s course towards total Russification became clearly defined. Since Zdorovyi did not cease his public and political activities, he was caught up in the next wave of arrests of the Ukrainian intelligentsia in 1972.

By spring, the “pressure surveillance” on him was already obvious. Zdorovyi was arrested on the street on June 21, 1972. It turned out that the documents for his arrest and search were not properly executed; at his demand, they had to be changed and corrected on the spot. The search lasted from noon until 4 a.m.

The investigation spent almost a year compiling 49 points of accusation of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” and “slanderous fabrications.” Zdorovyi demanded that the case be conducted in Ukrainian, was scrupulous about legal technicalities, and complained about the investigator, who had to provide explanations to higher authorities. Zdorovyi managed to steal the “Plan of Investigative Actions” from the investigator. For his persistence, he was placed in a punishment cell twice and underwent a psychiatric evaluation for 35 days.

The Kharkiv KGB intended to create an “anti-Soviet group” on paper, led by Zdorovyi. It conducted simultaneous searches at the homes of 9 individuals and arrested engineer Ihor Kravtsiv, whose case was only separated into a different proceeding at the end of 1972, as there was no “group”—only elementary manifestations of civic consciousness. About 220 people from different parts of the Soviet Union were interrogated in the case. The workers did not provide testimony, while some of the intelligentsia tried to protect themselves. To help his lawyer defend him, Zdorovyi formally pleaded partially guilty (to the factual side) but denied the aim of undermining and weakening the Soviet state and social order.

Zdorovyi was not allowed to hire a lawyer from another city. However, his defender handled the case wisely. The trial, which concluded on April 5, 1973, sentenced him to 7 years of imprisonment in strict-regime camps under Article 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR. The lawyer managed to get the sentence reduced to 4 years in the cassation court. The KGB then appealed to the Supreme Court of the USSR, complaining that the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR, with such a decision, was promoting “the development of nationalist anti-Soviet tendencies in Ukraine.” The Supreme Court of the USSR annulled the decision of the Supreme Court of Ukraine and sent the case for review by a new panel of the cassation court. While already in the camp, Zdorovyi was informed that his previous 7-year term had been reinstated. After this, the lawyer lost her clearance for political cases. Zdorovyi was still paying off the court costs (for chemical expert analyses) of 1,000 rubles even after his release.

Immediately after the trial, Zdorovyi was thrown into a death row cell at the SIZO on Kholodna Hora. He was transported from Kharkiv in July 1973 and arrived in August at the 36th zone of the Perm camps. He was among highly educated, dignified people: L. LUKIANENKO, Ye. SVERSTIUK, I. SVITLYCHNY, Ye. PRONIUK, O. SERHIYENKO, and Gunārs Astra. Following the beating of S. SAPELIAK by a guard on June 23, 1974, a protest strike erupted in the zone. Zdorovyi took an active part in it, for which he was thrown into a punishment cell, then into a PKT (cell-type solitary confinement), and at the end of 1975, he was sentenced by the Chusovoy District People’s Court to 3 years of prison, which he served in Vladimir Prison.

Zdorovyi was released in 1979 and remained under administrative surveillance for another 5 years. He earned 82 rubles a month as an engineer while still paying off court costs.

Zdorovyi was one of the initiators of democratic processes in the Kharkiv region and in Ukraine. As early as November 1985, he shared his draft charter for the “Spadshchyna” (Heritage) society with his inner circle (it was successfully registered in 1987). He participated in the creation of the Society for the Ukrainian Language, “Memorial,” the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, the People’s Movement of Ukraine (Rukh), and the Democratic Party of Ukraine (DemPU), where he held leadership positions.

In 1988, he was elected deputy chairman of the Council of the Labor Collective of the NPO “Energostal,” and from 1990–94, he was a deputy of the Kharkiv Oblast Council. In 1994, he completed a course on state and law at the Academy of Public Administration. From 1992 to 1994, he worked as the first deputy head of the Oblast State Administration for nationwide and regional policy and humanitarian issues; from 1994 to 1995, he managed a state financial institution; from 1999 to 2000, he was an economic advisor; and since 2000, he has been the Executive Director of the Institute of Political Sciences. He ran for the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine and for the position of city mayor.

On December 1, 2014, he was awarded the Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, 5th Class.

Since 1999, he has been retired. Despite losing his sight, he remains active in public affairs. Since 1995, he has headed the regional organization of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons. His son, Yaroslav, born in 1962, is a doctor. His wife, Lesia Yakivna, is a teacher.

Bibliography:

I.

Interview with A. Zdorovyi on July 1, 2002, in Kharkiv. https://museum.khpg.org/1313577718

II.

Lukianenko, Levko. Z chasiv nevoli. Knyha chetverta: Krayina Moksel [From the Times of Captivity. Book Four: The Land of Moksel]. – K.: Feniks, 2010. – pp. 213–219 et al.; Shliakh do vidrodzhennya: v 13 t. T. 8: Z chasiv nevoli: Krayina Moksel [The Path to Revival: in 13 vols. Vol. 8: From the Times of Captivity: The Land of Moksel] / Levko Lukianenko – K., TOV “Yurka Liubchenka,” 2014. – pp. 213–219 et al.

Kalinichenko, V.V., and Andriy Lymar. Na zakhyst ukrayinskoyi movy (Do 40-richchia hromadianskoho postupku) [In Defense of the Ukrainian Language (On the 40th Anniversary of a Civic Act)] // Z Bohom u sertsi, No. 2, 2006. – pp. 15–17.

Mizhnarodnyi biohrafichnyi slovnyk dysydentiv krayin Tsentralnoyi ta Skhidnoyi Yevropy y kolyyshnoho SRSR. T. 1. Ukrayina. Chastyna 1. [International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former USSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1]. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny,” 2006. – pp. 245–247. https://museum.khpg.org/1184358292

Rukh oporu v Ukrayini: 1960–1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk [The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960–1990. An Encyclopedic Guide] / Foreword by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. – K.: Smoloskyp, 2010. – pp. 250–251; 2nd ed.: 2012. – pp. 277–278.

Vasyl Ovsiienko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Last read August 4, 2016.