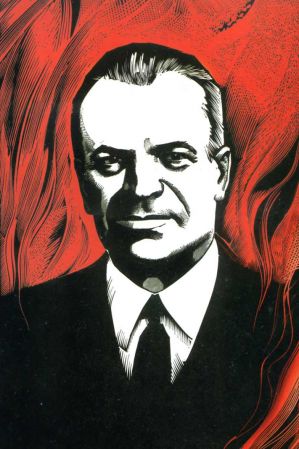

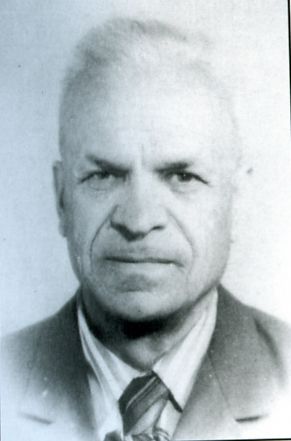

OLEKSA MYKOLAYOVYCH HIRNYK (born March 28, 1912, in the city of Bohorodchany, now Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast – d. January 21, 1978, in the city of Kaniv, Cherkasy Oblast).

Political prisoner. Committed self-immolation in protest against the colonial status of Ukraine.

He was descended from Boyko highlanders. His father, Mykola Hirnyk, graduated from the Ukrainian gymnasium in the city of Stanislav, served in the Polish army, was a member of Prosvita, and experienced both Polish prisons and Russian camps. His mother, Kateryna Bilichak, was a peasant.

Oleksa studied at a Polish school and then at the Stanislav Ukrainian gymnasium.

When Oleksa received his matura (certificate of education), he could not find work: the Poles demanded conversion to Catholicism. After gymnasium, his parents wanted to send him to a theological seminary, but he went to work for the patriotic organization “Sokil,” leading the Plast youth organization in Bohorodchany. He was preparing to enter the philosophy faculty of Lviv University.

He was conscripted into the Polish Army. He did not tolerate humiliation on national grounds. He once remarked, “I’m fed up with the odious Polish army. I want to exchange my konfederatka for a mazepynka.” In March 1937, a military tribunal of the Rzeczpospolita sentenced Private Hirnyk of the artillery to 5 years and 3 months of imprisonment “for treason to the Fatherland.” He was held in Lviv’s “Brygidky” prison, in the fortresses of Krakow and Tarnow, and in Bereza Kartuska. During the German-Polish war in September 1939, he escaped from prison.

On November 11, 1939, Hirnyk went to the city of Stryi to re-establish old contacts with the underground. The intelligently dressed man aroused suspicion in the militsiya. They checked his documents. Arriving at the station, Oleksa saw NKVD officers with dogs herding Poles into freight cars to deport them to Siberia. He tried to protect them, was beaten, and shoved into a car. Hirnyk escaped but was caught. Desperately fighting off several NKVD officers, he proclaimed the “Decalogue of a Ukrainian Nationalist.” During interrogations, he refused to testify. He was severely beaten and regained consciousness a day later. Since the prisons in Galicia were overcrowded, Hirnyk was transferred to the investigative unit of the NKVD administration in Zhytomyr Oblast. He did not betray anyone from the underground. Using materials from Polish special services, the NKVD tried to pin “connections with foreign countries” on him. Ultimately, the court sentenced Hirnyk under Article 54-10, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 8 years of deprivation of liberty in remote camps of the Soviet Union for “betrayal of the Motherland” and, in accordance with Articles 29(a) and 30 of the Criminal Code, to the deprivation of his electoral rights for 5 years after serving his sentence.

He served his sentence in the Urals. He cut timber in the taiga, broke stone in quarries, worked in an underground factory, and was repeatedly placed in punishment cells. In 1943, Hirnyk, as someone who knew Polish, was offered an officer position in the Polish army being formed in the USSR, but he refused. Once, Hirnyk tried to defend another prisoner from the arbitrary actions of a guard. The guard broke his right forearm with the butt of his rifle.

He was released in the late autumn of 1948. By that time, his mother and younger sister had died, and his brother Fedir had been killed at the front. Oleksa found none of his peers alive: 25 of his comrades from Bohorodchany had died in Demianiv Laz alone.

He worked as a digger at a brick factory in Stanislav. In 1949, he married Karolina Ivanivna Petrash, who had returned from exile. In 1953, the couple moved to the city of Kalush, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, to join Karolina’s brother, the disgraced Greek Catholic priest Mykhailo Petrash, who had also returned from exile. Their sons Markian (b. 1950) and Yevhen (b. 1954) were born.

Hirnyk was deeply distressed by the national oppression and the growing Russification. Taciturn, seemingly stern, but with a natural sense of justice, he was tolerant of people of different nationalities but reacted sharply to socio-political events. He traveled with his wife to Chernecha Hora (Monk’s Hill) in Kaniv, where, like an exposed nerve, he particularly felt the tragic statelessness of his Homeland. He was increasingly obsessed with the thought: “Why have I not known the joys of a free person who has his own state, his own truth?” He found the answer in T. Shevchenko, whose words peppered his speech. He was captivated by O. Honchar’s novel “The Cathedral” and promoted it. He brought from Lviv M. Braychevsky’s work “Reunification or Annexation?,” V. MOROZ’s “A Report from the Beria Reserve,” and I. DZIUBA’s “Internationalism or Russification?,” and spoke approvingly of prisoners of conscience, the human rights movement, and the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, seeing in them a continuation of the UPA’s struggle.

In 1976, Hirnyk built a kitchen on his property with a small room on the second floor, where he had a hiding place. There, he spent a long time handwriting leaflets directed against the Russian occupation and Russification of Ukraine. According to acquaintances, Oleksa became very thin in 1977. He wrote about 1,000 leaflets (8 versions are known). The leaflets contained rather lengthy reflections on the historical fate of the Ukrainian people, supported by quotes from T. Shevchenko.

In a farewell letter to his wife dated January 6, 1978, Hirnyk wrote, among other things: “I have walked a straight, thorny path. I did not stray, I did not falter. My protest is truth itself, not Moscow’s lie from beginning to end. My protest is the suffering, the torture of the Ukrainian nation. My protest is Prometheanism, a rebellion against violence and enslavement. My protest is the words of Shevchenko, and I am only his student and executor.”

He left a note on the table: “I went to Lviv. Don’t worry, I’ll be back in a day or two. Until we meet again, my dear! Oleksa. 19.1.1978.”

On January 20, 1978, Hirnyk visited Saint Sophia’s Cathedral and the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra in Kyiv (trolleybus tickets were found in his bag). At 7 p.m., he took the last bus from Kyiv to Kaniv. He had a bag with two canisters of gasoline—2.5 and 1 liter. He walked for over 3 km up Chernecha Hora against a strong, frosty wind. He circled the monument to Taras Shevchenko three times. He chose a spot on a lower terrace on the northern slope of Chernecha Hora, about 10-12 meters to the left of the observation deck (his bag, two empty canisters, and a lighter were found there). He took out the leaflets and scattered them to the wind, which dispersed them. On a granite boulder, he placed his final testament:

“A protest against the Russian occupation of Ukraine!

A protest against the Russification of the Ukrainian people!

Long live the Independent United Ukrainian State!

(Soviet, but not Russian).

Ukraine for Ukrainians!

On the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the proclamation of an independent Ukraine by the Central Rada on January 22, 1918 – January 22, 1978, in protest, Hirnyk Oleksa from Kalush has burned himself to death.

Is this the only way to protest in the Soviet Union?!.”

At approximately 3 a.m. on January 21, 1978, O. Hirnyk doused himself with gasoline and struck his lighter. He still moved about 10-12 meters. He found the strength to cut open his chest with a beekeeper’s knife...

The charred body, in the “boxer’s pose” characteristic of fire victims, was discovered by a police officer on patrol. The deputy chief of the district police department, Oleksandr Hnuchyi, called in police officers Captain Ivan Tereshchenko and museum security guard Sergeant Roman Kramarenko. They collected about 970 leaflets but hid a few of them. In a special room at the museum, the leaflets were counted and sorted by officers from the regional KGB administration. Their subsequent fate is unknown. Despite a strict KGB ban on speaking about the event, the entire city of Kaniv learned the name of Oleksa Hirnyk from Kalush from these very police officers. O. Hnuchyi’s wife, Vira, read 4 of the leaflets to people in Kaniv, Lviv, Drohobych, and Truskavets. The KGB officers gathered the museum staff and also warned them not to talk about the incident. A criminal case was opened by both the militsiya and the KGB. KGB agents also guarded the morgue.

His wife’s home in Kalush was searched. She was told that her husband had died in a car crash. Relatives were interrogated.

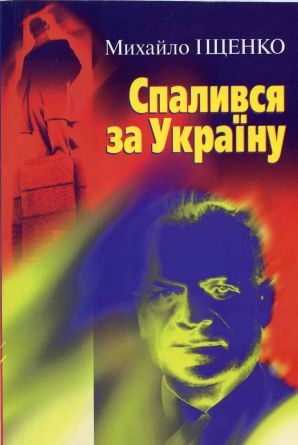

The body was examined and placed in a coffin, which the widow brought to Kaniv, by the forensic pathologist Mykhailo Ishchenko (who later published a series of articles and a book about Hirnyk). Meanwhile, agents spread false rumors that the deceased was a drunkard or a religious fanatic.

The priest Mykhailo Petrash held a panakhyda (memorial service) at the Hirnyk home at night. Defying the ban, his son Yevhen opened the coffin at night and bid a Christian farewell to his father.

Despite the prohibitions and silence, every year on January 21, someone would place a red viburnum branch at the site of the act. It was always trampled. On May 22, 1991, Patriarch Mstyslav (Skrypnyk) visited the site. He said: “Some may think that Oleksa Hirnyk is a suicide. But is one who goes to war for the Motherland—consciously going to his death for the sake of life—a suicide? I think God will forgive him. He gave his all to Ukraine, without reservation. He saw Shevchenko’s grave, Chernecha Hora, as the most powerful hearth of the Ukrainian national spirit, and he brought the flame of his great heart here. Oleksa Hirnyk will take a worthy place in the pantheon of the most outstanding fighters of the Ukrainian nation.”

On January 22, 1993, in the city of Kalush, a street was named in his honor, and a memorial plaque with a bas-relief was installed on his house. On May 28, 1995, a memorial sign was erected near his parents’ house in Bohorodchany, and a room-museum dedicated to O. Hirnyk was set up in the school.

In 1999, the Kyiv Charitable Foundation named after O. Hirnyk, “Ukrainian Word for Ukrainian Children,” was established (chaired by People’s Deputy and Prosvita member Yuriy Hnatkevych). In January 2003, the “Prosvita” society held an evening dedicated to Hirnyk’s feat. The Kyiv city organization of the URP “Sobor” and the all-Ukrainian “Prosvita” society named after T. Shevchenko declared 2003 the year of Oleksa Hirnyk. On June 25, 2003, a scientific conference, “Russification and its Impact on the Ethnopsychology and Ethnostructure of Contemporary Ukrainianness,” was held.

A viburnum bush was planted at the site of his self-immolation. In 2000, the director of the Shevchenko National Preserve, Ihor Likhovyi (later Minister of Culture), installed a one-and-a-half-ton boulder of red-grained granite. A portrait and a copy of Hirnyk’s leaflet are on display in the museum.

Hirnyk’s son Markian is a scientist and lives in Lviv; his son Yevhen is an engineer, was the first deputy chairman of the Kalush City Executive Committee, and a People’s Deputy of Ukraine of the IV and V convocations (2002, 2006).

By Decree of the President of Ukraine No. 28/2007 of January 18, 2007, for the courage and self-sacrifice shown in the name of an independent Ukraine, Oleksa Mykolayovych Hirnyk was awarded the title Hero of Ukraine with the award of the Order of the State.

Bibliography:

Ishchenko, M. “...Spalyvsia Hirnyk Oleksa z Kalusha” […Oleksa Hirnyk from Kalush Burned Himself to Death] // Literaturna Ukrayina. – February 20, 1992.

A. Rusnachenko, Natsionalno-vyzvolnyi rukh v Ukrayini. Seredyna 1950-kh – pochatok 1990-kh rokiv [The National Liberation Movement in Ukraine. Mid-1950s – Early 1990s]. – K.: Vyd. im. O. Telihy, 1998 – p. 214.

Tarakhan-Bereza, Z.P. “Samospalennia v imia vidrodzhennia Ukrayiny” [Self-Immolation in the Name of Ukraine’s Revival] // In her: Sviatynia [Sanctuary]. – K.: Rodovid, 1998. – pp. 484–493.

Yuriy Danyliuk, Oleh Bazhan. Opozytsia v Ukrayini (druha polovyna 50-kh –80-i rr. XX st.) [The Opposition in Ukraine (second half of the 1950s – 1980s)]. – K.: Ridnyi krai, 2000. – pp. 110-111.

Mykola Som. “Liudyna-smoloskyp” [The Human Torch]. – Literaturna Ukrayina, March 20, 2003; The same: Informatsiynyi biuleten (Kremenchuk), No. 14 (526), 2003. – April 10. The Human Torch; Statement of the organizing committee for the commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the death of Oleksa Hirnyk. – Informatsiynyi biuleten (Kremenchuk), No. 14 (526), 2003. – April 10.

Mykola Som. “Liudyna-smoloskyp” [The Human Torch]; Statement of the organizing committee for the commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the death of Oleksa Hirnyk // Informatsiynyi biuleten, No. 14 (526). – April 10, 2003.

Mykhailo Ishchenko. Spalyvsia za Ukrayinu: Khud.-biohraf. povist [He Burned Himself for Ukraine: An Artistic-Biographical Novella]. – K.: Vyd. tsentr “Prosvita,” 2004, – 128 p.

Halyna Harmash. “Poema vohniu. Pamiati Oleksy Hirnyka” [A Poem of Fire. In Memory of Oleksa Hirnyk] // Slovo Prosvity, no. 10 (283). – March 10-16, 2005.

Mykola Hvozd. “I odyn u poli voyin” [Even One Man in the Field is a Warrior] // Ukrayinske slovo, No. 5. – February 1-7, 2006.

Svitlana Koronenko. “Vchytysia nam ye u koho: Notatky pislia vruchernnia premiyi imeni O.Hirnyka” [We Have Someone to Learn From: Notes After the Presentation of the O. Hirnyk Prize] // Literaturna Ukrayina, No. 4 (5142). – February 2, 2006.

Yevhen Bruslynovskyi. “Nahoroda znaishla heroya cherez 29 rokiv: Oleksi Hirnyku bude vstanovleno pamiatnyk na mistsi samospalennia na Chernechii hori” [The Award Found Its Hero After 29 Years: A Monument to Oleksa Hirnyk Will Be Erected at the Site of His Self-Immolation on Chernecha Hora] // Ukrayina moloda, No. 12 (3043). – January 23, 2007.

“U Bohorodchanakh vshanovuiut Heroya Ukrayiny Oleksu Hirnyka” [Hero of Ukraine Oleksa Hirnyk is Honored in Bohorodchany] // Maidan-inform, March 25, 2007.

Serhiy Lukianchuk. “Rivniannia na Neoplymoho: Premiiu Oleksy Hirnyka vrucheno luhanskomu studentovi, yakyi cherez sud domihsia prava navchatysia ukrayinskoiu movoiu” [Emulating the Unburnt One: The Oleksa Hirnyk Prize is Awarded to a Luhansk Student Who Won the Right to Study in Ukrainian in Court] // Ukrayina moloda. – April 7, 2007.

Mykola Ishchenko. “‘Chy varti my ohnia sviatoho’” [“Are We Worthy of the Holy Fire”] // Literaturna Ukrayina. – May 10, 2007.

Nina Hnatiuk. “‘Za neyi dushu pohubliu’” [“I Will Lay Down My Soul for Her”] // Slovo Prosvity, No. 3 (432). – January 17, 2008.

Yuriy Hnatkevych. “‘Rosiyski mozhnovladtsi ta intelihentsiia maly b davno vybachytysia pered ukrayinskym narodom…’: Shcho skazav by Oleksa Hirnyk poslu Chornomyrdinu?” [“Russian Officials and Intelligentsia Should Have Long Ago Apologized to the Ukrainian People…”: What Would Oleksa Hirnyk Say to Ambassador Chernomyrdin?] // Informatsiynyi biuleten, No. 9 (758). – March 6, 2008.

Case No. 4953, from 21.01. – 17.03.1978, Kaniv Prosecutor’s Office.

Case No. 1190, NKVD Administration in Stanislav Oblast, 1940, under Art. 54-10 (anti-Soviet activity).

Mizhnarodnyi biohrafichnyi slovnyk dysydentiv krayin Tsentralnoyi ta Skhidnoyi Yevropy y kolyyshnoho SRSR. T. 1. Ukrayina. Chastyna 1. [International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former USSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1]. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny,” 2006. – pp. 138–142. https://museum.khpg.org/1184355561;

Rukh oporu v Ukrayini: 1960–1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk [The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960–1990. An Encyclopedic Guide] / Foreword by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. – K.: Smoloskyp, 2010. – pp. 85–86; 2nd ed.: 2012, – pp. 155–156.

Vasyl Ovsiienko, Yevhen Hirnyk. Last read August 4, 2016.