A key dissident figure, organizer of opposition rallies in Lviv in 1988.

Of the Carpathian Boykos. His mother, Kateryna Voloshchak, born in 1934, worked as a club manager and later as a tailor. Even after retirement, she led the village ensemble and staged performances. His father, Ivan Makar, born in 1927, was a member of the youth organization “Luh” and spent some time in the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army). He worked as a bookkeeper on a collective farm and helped the insurgents. When the threat of arrest arose, he joined the Soviet Army in 1950, despite having a deferment.

Ivan finished primary school in his home village and, in 1974, graduated from the Strilky boarding school, where M. HORYN once worked. His studies came easily to him. He was a participant in the all-Union physics Olympiad and regional mathematics and chemistry Olympiads. In 1974, he enrolled in the physics faculty of Lviv University. During the summer holidays, he earned extra money in a student construction brigade in Russia’s Non-Black Earth Region.

In 1975–76, along with students Petro Zhuk and Bohdan Ternopilskyi from the Ternopil region, Anatoliy Kryvyi from the Odesa region, and Oleksandr Kytsak from the Kyiv region, he participated in a clandestine organization called the “Union for the Struggle for Development,” which aimed to build a “correct” communism. They drafted a credo for the organization and wrote an anonymous letter to the 26th Congress of the CPSU. Ivan asked a fellow villager to type the texts on the collective farm’s typewriter. The organization ceased its activities on its own.

Influenced by life’s realities (“Speak a human language!”), Makar slowly matured to a national consciousness. He was interested in philosophy, but not the Marxist-Leninist kind. Conflicts arose during seminars. By his third year, Makar was elected head of the faculty’s student scientific society, and he had a chance to remain at the department of theoretical physics. In their 4th year, the students elected a composition for the Komsomol and trade union bureaus different from what the Party bureau recommended. Makar was elected head of the dormitory’s student council. The Party bureau declared these elections invalid. The “processing” of students began, involving KGB officers who labeled any deviation from the “Party line” in Galicia as “nationalism.” Two students were expelled. Previously an excellent student, Makar became a mediocre one, losing his prospects for a scientific career.

After graduating from the university in 1979, Makar went to work at the Mshanets secondary school in Staryi Sambir Raion. He taught physics and astronomy. He had good relationships with the students and their parents, but a conflict arose with the administration regarding work methods.

In January 1982, Makar got a job as an engineer at the Lviv “Atomenerhoremont.” He was sent to check welds at the Novovoronezh Nuclear Power Plant, where he discovered defects. He did not yield to threats to conceal them.

On May 8, 1982, Makar married Halyna Mykulych, and in 1983, their daughter Natalka was born. He worked as an engineer at the Boryslav Foundry and Mechanical Plant. He later found a job at the Prykarpatska Geophysical Expedition.

In November 1983, he was sent on a rotational basis to the city of Novy Urengoy, where he hoped to earn an apartment. He was hired as the head of the radiation safety service at the “Urengoytruboprovodstroy” trust for the construction of the “Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod” gas pipeline. He found that workers were not being checked for radioactive contamination, equipment was stored haphazardly, and other violations occurred. He tried to establish order, appealing to various institutions, but the trust manager threatened him: “You understand, in the spring we find ‘snowdrops’ here” (a euphemism for corpses). His appeals to institutions revealed that Makar was “not one of us” and even an “enemy.” A local KGB officer advised him to leave. In the summer of 1984, at a colleague’s birthday party, during Andropov’s anti-alcohol campaign, an attempt was made to get him drunk and poison him. In June, he was fired “for cause.” He went to the Central Committee of the CPSU with a complaint, but was told: “Well, how can it be that everyone is bad, and you alone are good?”

He returned to Ukraine. His younger brother helped him get his former job back as a teacher at the Novoandriivka eight-year school in Shyriaieve Raion, Odesa Oblast. He taught physics, chemistry, and physical education, and worked part-time as a carpenter and beekeeper on a collective farm, hoping to get housing. He enrolled in correspondence courses at the Odesa Pedagogical Institute in the physical education faculty. When Makar registered at his place of work, the local KGB became interested in him and confiscated his passport. The district education department forcibly transferred him to the village of Sakhanske in the same district as a teacher of physics and physical education. He lived in a small closet at the school. There was no hope of earning housing. The authorities constantly provoked conflicts. Complaints to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine were fruitless; the answer was well-known: “How can it be that everyone is bad, and you alone are good?”

In August 1987, friends registered Makar in a dormitory in Lviv, and an old friend, Petro Zhuk, head of a department at the Institute of Applied Problems of Mathematics and Mechanics of the Academy of Sciences of the UkrSSR, hired him as a first-category design engineer.

Starting in November 1987, Makar began attending a discussion club at the House of Builders. The conversations there were in Russian—Makar was the first to speak Ukrainian. In December, Bohdan HORYN came there with a lecture on national issues. This was a revelation for Makar. From B. HORYN, he received an issue of the journal “Ukrayinskyi Visnyk” (The Ukrainian Herald), the publication of which V. CHORNOVIL had resumed in July–August 1987. In January, B. HORYN was collecting signatures at the discussion club demanding the release of the last political prisoners; Makar helped him. At that time, V. CHORNOVIL distributed the theses of his future speech and challenged an official representative from the oblast party committee to a debate. The following Thursday, the House of Builders was occupied by another event. Makar asked, “Mr. Viacheslav, why didn't you call on people to gather at the monument to Franko?” —“And why didn't you do it?” This was a kind of authorization for Makar to gather people when the opportunity arose.

One Monday in June 1988, Lviv residents gathered at the House of Builders to create the Society for the Ukrainian Language. The premises were locked. Someone suggested going to ask the second secretary of the city party committee, Adam Martyniuk. Makar, however, made a demand: if they didn't open in five minutes, we go to the monument to I. Franko. This was said confidently, by a man who knew what to do. People followed him, especially since the former political prisoner, artist Stefaniya SHABATURA, took him by the arm. The founding meeting, which took place on the pedestal of the monument to I. Franko, was effectively led by Makar. After it, a spontaneous rally began. When one of the speakers expressed the thought of why the delegates elected to the 19th Party Conference did not consult with the people, Makar had the idea to schedule a meeting with the delegates right there for the following Thursday, June 23. An initiative group was immediately elected: Makar, Ihor Derkach, Oksana Krainyk—the daughter of political prisoner Mykola Krainyk. Later, Iryna Kalynets and Yaroslav Putko were co-opted into the initiative group for the meeting with the party conference delegates.

Meanwhile, the authorities decided to take control of the Society for the Ukrainian Language and scheduled a second constituent meeting at the House of Builders for June 20. There, B. HORYN and Makar were added to the previous leadership of the Society.

To organize the meeting, Makar took a three-day leave of absence. The authorities planned to hold the meeting inside the House of Builders. After consulting with Iryna KALYNETS, Makar agreed, although they actually intended to lead the people to the monument to I. Franko. At night, Makar and I. Derkach posted announcements. The next day, at the demand of the people, Iryna KALYNETS brought the party conference delegates from the House of Builders, among whom were the first secretary of the city party committee, Volkov, and Academician Ihor Yukhnovskyi. Their opponents were Mykhailo and Bohdan HORYN, Viacheslav CHORNOVIL, Iryna KALYNETS, Yaroslav Putko, and Sheremeta. As the initiator, Makar led the rally. National and linguistic issues were raised, and there was talk about the closure of national schools. The rally had a loud resonance in Ukraine and throughout the world.

Makar scheduled the next rally for Thursday, June 30, near the stadium. Rumors spread that tanks were being prepared to enter the city. About 100,000 people gathered. There was no sound system, so here and there people spoke with megaphones or without them. Seeing that the rally was falling apart, I. KALYNETS called on the people to disperse. However, Makar still scheduled the next rally for July 7 at the monument to I. Franko.

Sensing he might be detained, Makar disappeared on the eve of the rally. The militsiya and KGB searched for him unsuccessfully, but he appeared directly at the rally at 7 p.m. The rally had started earlier, but Makar took charge and announced that they would discuss the creation of a Democratic Front to Promote Perestroika and national symbols. As agreed, the communists were announced by a journalist from the newspaper “Leninska Molod” (Lenin’s Youth), Viktoriya Andreeva. In his speech, Makar emphasized the need to erect monuments in every village to the fighters who died for Ukraine’s freedom. To a written question asking if he meant the Banderites, Makar replied: “Yes, and those who are called Banderites.” This became the main accusation against him after his arrest. Right then, Makar and the HORYN brothers and V. CHORNOVIL announced the transformation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group into a Union. At the same time, Makar scheduled the next rally for August 4 and, according to the indictment, “called on those present to organize strikes and unrest if the authorities did not grant permission for such a gathering.”

After the rally on July 7, which shook Lviv and all of Ukraine, Moscow’s “Komsomolskaya Pravda” published an article titled “The Fables of Makar's Father,” and the local communist press unanimously condemned his speech and actions. The authorities called a press conference at the House of Journalists with the participation of the HORYN brothers, Makar, and CHORNOVIL, where the latter distanced himself from what Makar had said about the Banderites. Then the authorities gathered people in the border village of Halivka, where Makar was born, to discredit him by having him debate a historian, the director of the Staryi Sambir school, Rashkevych. The whole event was to be filmed for television. Makar planned to go with M. HORYN and two friends, but the authorities feared a debate with M. HORYN, and the border guards did not let him and his friends pass. Makar didn't go either. Meanwhile, the village was surrounded by soldiers.

Criminal case No. 181-0011 against Makar was opened on July 21, 1988. However, he was first summoned for questioning late in the evening of July 28, to intimidate him: he was seated in the middle of a hall under spotlights and interrogated by several people in turns.

On the morning of August 4, the regional prosecutor's office searched Makar's dormitory room and workplace, confiscating three printed copies of the Declaration of Principles of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union (UHU). At the prosecutor's office, he was personally searched and charged under Article 71 (“Mass Disorders”) and 187-1 (“Dissemination of Knowingly False Fabrications Slandering the Soviet State and Social System”). A month later, on September 9, Article 71 was changed to the milder Article 187-3 (“Organization of or Active Participation in Group Actions that Violate Public Order”). The investigation was conducted by a group of 4 investigators headed by the chief of the second investigative department of the regional prosecutor's office, V. K. Shymchuk. Makar immediately declared an indefinite hunger strike, which he maintained for 35 days. For the first ten days, he was held with four or five other arrested individuals, then he was separated. During the hunger strike, he lost 16 kg. In the prison library, he received Marx's “Capital” and diligently studied it. He was at peace, as the investigators did not bother him much. After all, this was a time when the last political prisoners were being released, and a powerful wave of protests in Ukraine and around the world had risen in support of Makar. A Public Committee for the Defense of Ivan Makar was created, headed by the chairman of the Lviv branch of the UHU, B. HORYN. Physically, Makar felt satisfactory. He was not force-fed but was sustained with glucose injections. He occasionally lost consciousness. The investigation allowed a visit from his brother Volodymyr, at whose request Makar ended his hunger strike. The investigators tried to gather any evidence of Makar’s inadequate behavior to have him committed for psychiatric “treatment.” But his wife and brother Volodymyr categorically rejected such demands and refused to provide such evidence.

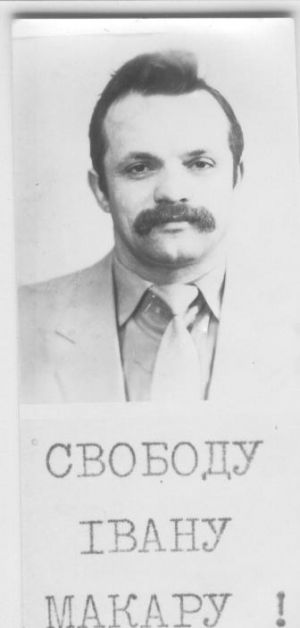

In early November, Makar was offered the chance to write a repentant statement in exchange for his release. He refused, stating that he was fine where he was, and that he had nowhere to live on the outside. Then they took away all his writings and, on the cold evening of November 9, 1988, pushed him out of the pre-trial detention center. He put on all his clothes and walked out—with a beard. That same evening, he met B. HORYN, who, along with his supporters, was distributing his photos with the caption: “Freedom for Ivan Makar!” On November 15, 1988, Makar was informed that the case against him was closed due to a lack of evidence of a crime under Article 187-1 and due to unproven participation in a crime under Article 187-3.

He immediately joined the struggle. In November, he spoke at an environmental rally in Kyiv, calling the government an occupying power.

On December 10, 1988, Makar was again detained by the militsiya in Lviv near I. Franko Park, accused of disobeying the militsiya, and sentenced under Article 185 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the UkrSSR to 15 days of administrative arrest.

On February 19, 1989, Makar was accused of violating the established order for organizing and holding gatherings: allegedly, he gathered a crowd of about 100 people on Lenin Avenue and called for the erection of a monument to S. Bandera, and vilified the Communist Party and the Soviet government. He was arrested for 15 days.

Under the same accusation, he was imprisoned for 15 days on March 12, 1989—in reality, because M. Gorbachev was scheduled to visit Lviv three days later. Bard Andriy Panchyshyn wrote a popular song about this incident: “God forbid there are terrorists, or Makar pops out — he could unnerve the General Secretary.”

On May 5, 1989, Makar was again imprisoned for 15 days for participating in an unsanctioned rally in Rynok Square. And on May 19, he was accused of, while in the detention center in Lviv in cell No. 1, repeatedly “holding meetings among the detainees, in his speeches calling for unsanctioned rallies and demonstrations, against the leaders of Soviet and party bodies, and for the separation of the Ukrainian SSR from the USSR.” The judge added another 10 days to his arrest.

After his release in November 1988, Makar joined the Ukrainian Helsinki Union and participated in the discussion of its Declaration. Being an opponent of the clause on a confederation of republics, he left the UHU in the spring of 1989. Together with Hryhoriy PRYKHODKO, he created the Initiative Group for the Restoration of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, with the intention of later turning the group into a party. Feeling that he could not control its activities, Makar resigned two weeks before the founding congress of the Ukrainian National Party (later the Ukrainian National Assembly), which was based on the group. Makar did not join the People’s Movement for Perestroika (Rukh) due to the vagueness of its ideology and the prevalence of KGB agents, as well as its first leadership, which he clearly disliked.

He participated in several meetings of representatives of initiative groups of national-democratic movements of the peoples of the USSR, including in Lithuania, Latvia, and in April 1989 in the town of Loodi in Estonia. There, Makar, H. PRYKHODKO, and Volodymyr SICHKO criticized the UHU for not daring to declare that it was fighting for the independence of Ukraine. In Vilnius in January 1989, Makar initiated the adoption of a statement by the enslaved peoples.

This was possibly one of the impetuses for the UHU to eventually change its program and declare that it too was fighting for independence. More moderate politicians stopped inviting Makar to rallies. He last spoke in the summer of 1989 on Mount Makivka, calling the Soviet government and its troops occupiers.

From the summer of 1989, Makar did not show political activity and returned to his scientific work at the Institute of Problems of Mechanics and Mathematics, intending to defend his dissertation. But his friend Vasyl Fedorchak came to him and informed him that in the Staryi Sambir electoral district No. 279, almost exclusively Soviet nomenklatura were running for the Verkhovna Rada of the UkrSSR, who would not defend the interests of the people, and that Rukh was supporting a KGB agent in the elections. The first meeting to nominate Makar, called by Fedorchak in the village of Holovetske, near the village where Makar had once taught, was disrupted by the communists. Then Fedorchak initiated a second meeting, which nominated Makar as a candidate. Makar won in the first round with 52% of the votes and became a People's Deputy on March 4, 1990.

Initially, Makar was a member of the opposition faction “Narodna Rada” (People’s Council), but in October 1990, he publicly announced his withdrawal because “Narodna Rada” refused to discuss his concept for transitioning to a market economy. He left it so as not to bear responsibility for its activities. He diligently worked as secretary of the Verkhovna Rada’s commission on legislation and legality.

He lived in the “Moskva” hotel, while his family was in Boryslav. In 1991, his second daughter, Olha, was born. In October, his wife and children moved to Kyiv. They lived in a hotel, enduring hardship: during the period of inflation and the plundering of Ukraine, it was a problem to buy milk for the child without food coupons. A deputy’s salary at that time was meager. Attempts were made to “buy” Deputy Makar, but he replied: “I am, of course, for sale: but I have already sold myself once to the voters, and I cannot sell myself to you a second time.”

In the March 1994 elections, he ran in Drohobych electoral district No. 267. He received 1.66% of the votes because Rukh nominated its own candidate there, and the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists (KUN), which had initially promised Makar its support, supported the candidate from Rukh.

In the summer of 1993, Makar filed a crime report with the Prosecutor General’s Office against Prime Minister L. Kuchma. Later, in November 1994, he informed the Prosecutor General about the treason of President L. Kuchma, who had previously signed a document with Russia on the Interstate Economic Committee, where Ukraine had 16 votes and Russia 50. Neither the Prosecutor General’s Office nor the Supreme Court reacted. Then, on March 13, 1995, Makar registered his own newspaper, “Opozytsiya” (Opposition), where he published his lawsuits and articles. Each issue of the newspaper had to be printed at a different printing house, some secretly. Finally, on the eve of 1996, the entire print run of an issue was destroyed at the “Kyivska Pravda” publishing house. On November 16, 1995, Deputy Prosecutor General Aleksandrov opened a criminal case against Makar; his home was searched, and his computer was confiscated. On March 13, 1996, a year after its registration, the newspaper, into which Makar had invested all his assets, was shut down.

By a verdict of the Vatutinskyi District Court of Kyiv dated June 27, 1996, Makar was sentenced to 2 years of imprisonment with a two-year suspended sentence. During the trial, Makar was on a hunger strike for 37 days. Under the terms of the verdict, he was not allowed to travel anywhere, had to report to the militsiya monthly, and could not find a job. The family suffered from poverty. The authorities refused to re-register his newspaper.

Since 1991, Makar had been studying by correspondence at the Taras Shevchenko National University, and on June 21, 1996, six days before the verdict, he received a law degree. Since November 1998, he has been working as a lawyer, teaches constitutional law, and occasionally publishes. Since then, he has participated in the court proceedings of a large number of high-profile cases. For instance, he sought to bring to criminal responsibility former NKVD officers who were involved in the executions in the Bykivnia forest. He is still pursuing a case in the courts and prosecutor’s offices regarding O. Buzyna’s article “Taras Shevchenko the Ghoul,” published in the newspaper “Kievskie Vedomosti,” and a corresponding book. In early 2000, as a public prosecutor, he brought charges against L. Kuchma and participated in the “Ukraine without Kuchma” campaign. He submitted a report on the crimes of NKVD officers who operated under the guise of Banderites in Western Ukraine.

He is suing President Yushchenko and the Government in court over the recognition of the UPA as a belligerent party, the cancellation of agreements on paying pensions from the Ukrainian budget to retirees of the Black Sea Fleet and other Russian citizens, and regarding inaction in neutralizing the subversive activities of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine, and regarding the issuance of secret decrees, resolutions, and orders.

After a lengthy legal battle, he achieved the cancellation of the decision to refuse to open a criminal case against Kuchma and the referral of the materials to the Prosecutor General’s Office for additional review. He represented in court people who were beaten near the Central Election Commission in the autumn of 2004. He appealed to the prosecutor’s office to open a criminal case against individuals who vilified Ukrainians on the First National and “1+1” television channels. He is defending student Serhiy Melnychuk from Luhansk, who demanded instruction in the Ukrainian language, from persecution.

He lives in Kyiv.

Bibliography:

I.

“Nazvaty sebe demokratom lehko” [It’s Easy to Call Yourself a Democrat] / Holos Ukrayiny, 1991 – April 30.

“Ya vkushal plody vlasty nad tolpoy” [I Tasted the Fruits of Power Over the Crowd] / Vechernie Vesti, 1997 – November 5.

“Moya borotba” [My Struggle] / Postup, 2006 – January 16.

Interview of I. Makar with the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, May 29 and 30, 2000.

II.

“Svoboda zboriv: demokratiia i zakonnist. Mitynh bilia pamiatnyka Ivanovi Franku” [Freedom of Assembly: Democracy and Legality. A Rally at the Monument to Ivan Franko] / Leninska molod, 1988. – July 12.

S. Zonov. “Pro rizni vitryla hlasnosti” [On the Different Sails of Glasnost] / Vilna Ukrayina, 1988. – July 13.

V. Panov. “Bayky ‘batky’ Makara” [Fables of ‘Daddy’ Makar] / Komsomolskaya pravda, 1988. – Around July 8–15.

L. Sukhonos. “Horia z pamiati ne vykreslysh” [You Cannot Erase Grief from Memory] / Vilna Ukrayina, 1988. – July 14.

Mykhailo Batih, Maksym Khramov, Sviatoslav Yavorivskyi. “Spadshchyna i nashchadky” [Heritage and Descendants] / Leninska molod, 1988. – July 17.

P. Lekhnovskyi. “Ne v toy bik, Ivane” [The Wrong Way, Ivan] / Vilna Ukrayina, 1988. – July 20.

Informatsiynyi biuleten No. 1 (spetsialnyi vypusk) Lvivskoi oblasnoi filii UHS ta Hromadskoho komitetu zakhystu Ivana Makara [Information Bulletin No. 1 (Special Issue) of the Lviv Oblast Branch of the UHU and the Public Committee for the Defense of Ivan Makar]. August 20, 1988 (typescript). – 20 p.

L. Sukhonos. “Davno vytsvili khoruhvy i khto yikh prahne ozhyvyty” [Long-faded Banners and Who Seeks to Revive Them] / Vilna Ukrayina, 1988. – November 11.

L. Sukhonos. “Patriotyzm – tse liubov i sovist” [Patriotism is Love and Conscience] / Vilna Ukrayina, 1988. – December 21.

Pravda Ukrainy, 1989. – February 9.

I. Zadorozhnyi. “U poloni emotsii” [In the Thrall of Emotions] / Vilna Ukrayina, 1989. – April 28.

N. Klymkovskaya. “Ivan Makar: ‘Lazarenko ne razhovaryval by na polusohnutykh’” [Ivan Makar: ‘Lazarenko Wouldn’t Speak on Bended Knee’] / Polityka, 1999 – April 7.

Vasyl Ovsiienko. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. June 25, 2007. Corrections by I. Makar July 7, 2007.

MAKAR IVAN IVANOVYCH

MAKAR IVAN IVANOVYCH