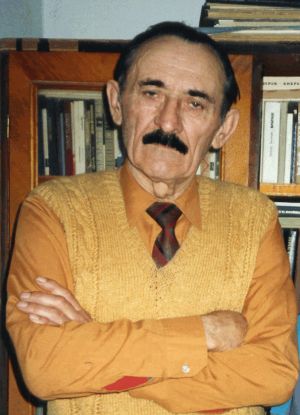

Writer, public figure.

On his mother's side, Sirenko is descended from the Danubian Sich Cossacks who were resettled in the Azov region. His mother, Tetyana Antonivna Mamchenko (1906–1978), was poorly literate but possessed a natural peasant wisdom; she knew countless folk songs and was a good seamstress. His father, Ivan Andriyovych Sirenko (1906–1985), worked variably as the head of a consumer cooperative, in the village council, or as a collective farm chairman, so he was moved from village to village.

Before the war, Volodymyr finished four grades at the Dolynska school. In 1941, as a ten-year-old boy, he and his father drove cattle and horses to the North Caucasus. He was evacuated to the city of Arzigir, then to the village of Velychayivka, Urozhaynitsky Raion, Stavropol Krai.

As the Germans retreated, the family moved to the Donbas, where his father got a job at a mine. Eventually, the family returned to the village of Novospasivka (now Osypenko), where Volodymyr continued his studies, and then moved to the village of Komyshuvatka, Prymorsk Raion. From there, Volodymyr enlisted for the reconstruction of the national economy. In 1948–1950, he trained as a steelworker’s apprentice at a vocational school at the Dniprodzerzhynsk Metallurgical Plant. At the same time, he completed evening secondary school. During this period, his poems and articles were published in the city newspaper “Dzerzhynets.” In the summer of 1950, Mykola Tytarenko, a correspondent for the newspaper “Pravda” in Dniprodzerzhynsk and Dnipropetrovsk, offered the talented young man a job at the city radio broadcasting office. He worked for a short time in Berdyansk at the newspaper “Bilshovytska Zirka” and then returned to Dniprodzerzhynsk. Unable to find journalistic work, he became a supervisor in a dormitory for young workers.

In 1952, Sirenko married Tetyana Tymofiivna Kliuchnykova, a worker and a Ukrainian from the Sumy region. In 1953, their daughter Liudmyla was born, followed by Olha in 1962.

From 1953–1956, Sirenko served in the airborne troops in Pskov. He graduated from the junior commanders' school, was a squad commander, and had 24 parachute jumps to his credit. He joined the CPSU while in the army. Because of his good voice, he was accepted into a song and dance ensemble. He worked for the division newspaper and was published in Leningrad and Moscow newspapers and magazines. He was offered a career in journalism, but he preferred to return to Ukraine. In 1956, he was demobilized with the rank of sergeant.

After demobilization, he worked as a literary contributor for the newspaper of the Dzerzhinsky plant, “Znamia Dzerzhynky,” and later as its executive secretary. In 1963–64, he became the editor of the Ukrainian-language newspaper of the railway car manufacturing plant, “Vahonobudivnyk.”

From 1958 to 1964, Sirenko completed a correspondence course in the Russian department of the philology faculty at Dnipropetrovsk University. His poems were published in the newspapers “Komsomolskaya Pravda” and “Pravda,” and in the magazine “Novy Mir.” In 1964, the “Promin” publishing house released Sirenko’s first book of poetry, “Rozhdeniye pesni” (The Birth of a Song). With such successes, he decided to return to his native language. It was a difficult choice. The poet Mykhailo Chkhan advised him to translate his best poems into Ukrainian. He did not translate them, but rather re-sang them. Meanwhile, Sirenko listened to Radio Liberty and heard broadcasts from Bulgaria, Hungary, and Poland—all in their native languages, while for Ukrainians, almost everything was in Russian. He concluded that he was not a Russian, but without his native language, he was not a Ukrainian either, just a _kuraïna-perekotypole_ (a tumbleweed). Sirenko became an active defender of the Ukrainian language, a fighter against the national oppression of his people. His return to his native language sparked a creative surge, and he wrote poems condemning Russification, which he read publicly to audiences. He raised social issues and the problems of morality within the higher party leadership.

At a meeting of ideological workers in Dnipropetrovsk, the first secretary of the regional committee, O. Vatchenko, who recognized himself in the poem “The Wall,” shouted and stomped his feet: “Here in Dniprodzerzhynsk, a poet works as the editor of the newspaper at the railway car plant. He writes anti-Soviet poems, and lately, he’s started writing with a nationalist slant. He has no place in the Party!”

Sirenko was registered with the party organization of the railway car plant's administration, where he might not have been expelled from the Party. Therefore, he was transferred to the party organization of the car assembly shop, where few knew him. In the autumn of 1967, a meeting was convened, and Sirenko was expelled from the CPSU “for reading ideologically harmful poems that distort Soviet reality among workers and youth.”

Sirenko appealed to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. I. Hrushetsky, who chaired the meeting of the Party Control Committee, said: “Comrade Sirenko still has a lot of trash in his head. Let him walk around and think, and in a year or a year and a half, we will return to his issue.” At that, his Cossack blood boiled over: “In the corridors of the Central Committee, everyone wears karakul hats. I wear a rabbit-fur one. Issue me a karakul hat, maybe my thinking will change under it.” Hrushetsky threw him out with “a state-sponsored curse.” An attempt to defend himself at the Party Control Committee in Moscow, where he had a conversation with Politburo member Grishin, was equally futile. He returned without his party card, but with his human dignity.

The KGB accused him of writing and distributing “anti-Soviet and nationalist poems, criticizing certain Soviet and party officials.” A case was opened against him. He was facing the camps of Mordovia, but his childhood friend, Colonel Havyaz, who held a very high position in the republican KGB, advised the regional KGB officers not to resort to extreme measures but to conduct “prophylactic work” with him. This work lasted for more than 20 years, until Havyaz retired.

Sirenko's works were no longer published. He was summoned countless times for “prophylactic” conversations and interrogations at the regional KGB department, especially after Radio Liberty and Voice of America broadcast stories about him.

Sirenko's circle of acquaintances expanded: he met with Borys ANTONENKO-DAVYDOVYCH, Oksana MESHKO, was friends with the family of Oleksandr and Olena Kuzmenko, with Oleksa TYKHYI, Oles Zavhorodniy, Borys DOVHALIUK, Vasyl Skrypka, Ivan BROVKO, Ivan Honchar, Ivan SOKULSKYI, Viktor Savchenko, Mykola KUCHER, and others.

The first search of his apartment took place on December 11, 1969, in the case of M. BERESLAVSKY, who attempted self-immolation in protest against Russification. Sirenko acted as a witness in his defense and stated that Russification was indeed happening. On March 6, 1972, his apartment was searched in the case of the poet Mykola KHOLODNYI. The third search was on March 19, 1985, in connection with the fabrication of a criminal case against him.

For some time, Sirenko edited technical manuscripts at the Dnipropetrovsk experimental laboratory of the Ministry of Ferrous Metallurgy. But when the campaign of persecution against Oles Honchar for his novel “The Cathedral” began in the spring of 1968, Sirenko wrote a letter in support of the writer. He was fired again, so he went to spend the summer with his aunt Hanna in the village of Novospasivka, where he fished, sold his catch, and lived on the proceeds. He was frequently summoned to the regional KGB, and street provocations were staged against him. After long ordeals, on March 9, 1971, Sirenko was finally hired at the Dnipropetrovsk Institute of Mineral Resources, where he edited technical reports and scientific articles.

In 1981, the “Promin” publishing house did release his book of poems “Batkove pole” (Father's Field), but as “counter-propaganda” to show the foreign “voices” that Sirenko was being published. In the book, the word “Ukraine” was replaced with “fatherland,” and the word “Cossacks” was removed altogether. Part of the print run was indeed exported. Despite the book's publication, surveillance continued.

At work, Sirenko was also forced to handle the printing of forms. He established good relations with a printing house in the town of Kobeliaky, which, due to a paper shortage, sometimes printed forms on credit. Seeing that the printing house used abacuses for calculations, Sirenko asked the management of his institute to repair a scrapped calculator and gave it to the printing house. The “competent authorities” took advantage of this. The Amur-Nyzhnodniprovskyi district party committee received a complaint about the “illegal” transfer of the calculator. And although there was no claim from the institute about “theft” and “abuse of office,” although the investigator objectively covered the “case,” and although Judge Lysenko refused to issue a guilty verdict, a different court panel was appointed, which, on May 23, 1984, delivered the verdict of the Amur-Nyzhnodniprovskyi district court: 2.5 years of exile and forced labor.

In early June, Sirenko was sent to the town of Kamyzyak, Astrakhan Oblast. The local police officer, Major Bulychov, after talking with the convict and reviewing the case, understood that it was fabricated by the KGB and, out of sympathy, assigned him the job of commandant of a dormitory for “khimiki”—convicts sentenced to forced labor. Sirenko was treated well by the police, the convicts (to whom he provided legal and human rights assistance), and the local—mostly Kazakh—population.

When the time of “glasnost” and “perestroika” arrived, Sirenko managed to have his case reviewed. He appealed to the 27th Congress of the CPSU. The Prosecutor General of the USSR protested the verdict, and the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR on May 3, 1986, overturned the verdict due to the absence of a crime in Sirenko's actions. On May 9, he returned home.

In the autumn of 1987, Sirenko was summoned to the Party Control Committee of the Central Committee of the CPSU and was reinstated in the Party with his 22 years of lost seniority restored. At the end of 1987, he also succeeded in having all his previously confiscated works returned.

As a rehabilitated person, Sirenko was reinstated at his old job and received compensation. He worked as an editor for regional television, hosting his own shows, “Ne pole pereity” (It's Not a Field to Cross) and “Z dushi i sertsia” (From the Soul and Heart). In 1989, as planned, Sirenko demonstratively surrendered his party card to the Zhovtnevyi district committee of the CPU in Dnipropetrovsk. He forced the regional KGB and the regional prosecutor’s office to assemble the staff of the institute where he had worked before the trial and to apologize to him.

In December 1992, Sirenko received a letter from the head of the SBU in the Dnipropetrovsk region, V. M. Slobodeniuk, with an apology and a certificate of rehabilitation. He also forced the editors of the regional newspaper “Zorya” to publish an apology for the slander they had previously printed about him.

Today, Sirenko is a well-known poet, prose writer, playwright, and publicist, a member of the National Writers' Union of Ukraine since 1990, a laureate of the “Blahovist” literary prize for his book “Velyka zona zlochynnoho rezhymu” (The Great Zone of the Criminal Regime), and the author of 10 collections of poetry and prose, including: “Korin moho rodu” (The Root of My Kin) (1990, “Radianskyi pysmennyk”), “Holhofa” (Golgotha) (1992, “Polihrafist”), “Navprostets po zemli” (Straight Across the Land) (1994, “Dnipro”), “Vse bulo” (It All Happened) (1999, “Polihrafist”). The book “The Great Zone of the Criminal Regime. On the Persecution and Repression of Ukrainian Dissidents in the 70s–80s of the Last Century” was published in 2005 by the “Porohy” publishing house with the assistance of Fidel Sukhonos. It is valuable for its honest testimony about many dissidents and participants in the human rights movement.

For his significant personal contribution to the national and state revival of Ukraine, selflessness in the struggle for the affirmation of the ideals of freedom and independence, and an active civic position, as stated in the Decree of the President of Ukraine of November 26, 2005, Sirenko was awarded the Order of Merit, Third Class.

He lives in the city of Dniprodzerzhynsk.

Bibliography:

I.

Sirenko, V.I. Velyka zona zlochynnoho rezhymu. Pro peresliduvannia ta represiyi ukrayinskykh inakodumtsiv u 70–80-kh rokakh mynuvshoho stolittia [The Great Zone of the Criminal Regime. On the Persecution and Repression of Ukrainian Dissidents in the 70s–80s of the Last Century]. – Dnipropetrovsk: Porohy, 2005. – 273 p.

II.

Tereshchenko, Rem. “Zhodnoho druha ne zradyv i v zhodnim riadku ne zbrekhav” [He Betrayed No Friend and Lied in No Line] // Vidrodzhena pam’iat. Knyha narysiv [Revived Memory. A Book of Essays]. – Dnipropetrovsk: Scientific-Editorial Center of the Regional Editorial Board for the Preparation of Publications of the Thematic Series “Rehabilitated by History.” Vol. 1. – 1999. – pp. 570-578.

Kotsiubynska, Mykhailyna. “Literatura faktu: mizh ‘velykoyu’ i ‘maloyu’ zonamy” [The Literature of Fact: Between the ‘Great’ and ‘Small’ Zones] // Berezil, No. 9. – 2006.–pp. 156-173.

KhPG Archive: interview with V. Sirenko on April 1, 2001, in the city of Kamianske (Dniprodzerzhynsk).

Vasyl Ovsiienko. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. March 7, 2007. Corrections by V. Sirenko April 27, 2007.

SIRENKO VOLODYMYR IVANOVYCH