A participant in the Sixtiers movement (the Vyshhorod group). Produced and distributed samizdat.

The Kondriukov family descended from enserfed Cossacks. His father, Oleksandr Kyrsanovych (b. 1910), worked on a kolkhoz and, before the war, in a mine. He was killed at the beginning of the war. His mother, Maria Ivanivna (née Kulishova, b. 1908), was left with five children: Dmytro (b. 1929), Mykola (1931), Yevdokia (1934), Vasyl (1937), and Alla (1941).

Vasyl started school in 1944. In 1946, kolkhoz workers received nothing for their labor days, and the taxes on fruit trees, livestock, and chickens were unbearable. In December, a famine began. His older brother Dmytro dropped out of school and went to work in a mine, where they gave out 250 grams of bread per dependent. This is how the family survived the winter. In the spring, the children ate blossoms and non-poisonous grasses. After the harvest, Vasyl gathered leftover ears of grain in a plowed field and was beaten with a whip by the kolkhoz rider.

Vasyl completed seven years of schooling in his village in Ukrainian. The students wrote between the lines on pages torn from various books; ink was made from elderberries. For grades 8–10, he walked 8 km to a Russian-language school in the village of Mykhailivka. He graduated in 1955, studied for a year at a school for agricultural electrification, and then got a job at a mine in Mykhailivka. From 1957 to 1960, he served in the signal corps in Kyiv, where he joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), thinking it was a way to “get ahead in life” and do something useful for his people. He later realized this was a mistake. After demobilization, he returned to the mine, working various jobs.

In June 1961, he set out “to see the world” in search of a different fate. He ended up in Vyshhorod at the construction of the Kyiv Hydroelectric Power Plant. He worked as an electrician in the Hidrospetsbud administration. He lived first on a guard barge, then in a dormitory, and later in a cold metal trailer. There, in 1963, he married Zinaida Tarasivna Matlaieva, an economist. He met critically minded workers. They would sometimes gather to discuss political issues, even jokingly calling themselves the Party of Real Communism (PRC). Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s novella “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” (from the journal Novy Mir) reached this circle very early. Kondriukov met the poet Volodymyr Komashkov and later Oles NAZARENKO, who had access to samizdat literature. O. NAZARENKO actively reproduced and distributed Ukrainian samizdat.

The flow of samizdat literature was growing, and not everyone who wanted to could keep up with the reading. So, NAZARENKO and Kondriukov bought a photographic enlarger. Together, they photographed and made prints in the trailer where Kondriukov lived, and later in his apartment in the Vitriani Hory neighborhood. At NAZARENKO’s request, Kondriukov also hired a typist, Larysa Filatova, to retype texts and paid her so that, in case of an interrogation, she could say she did it for money. They did not think about being arrested, but a natural instinct for self-preservation dictated a primitive level of conspiracy.

At the construction of the Kyiv Hydroelectric Power Plant, a group of critically minded young workers interested in politics and culture formed, including O. NAZARENKO, V. Komashkov, Oleksandr DOBAKHA, Ivan HONCHAR, Valentyn Karpenko, Bohdan Dyriv, and many others, up to a hundred people. The idea of creating an underground organization arose but was promptly abandoned: with its inevitable discovery, they would have been accused of “treason against the Motherland,” which carried the death penalty. They had no program documents or statutes. They limited themselves to cultural activities and criticism of the existing system, under the guise of Marxism-Leninism. The self-awareness of this circle quickly evolved toward the idea of Ukrainian statehood.

In 1964, Viacheslav CHORNOVIL appeared at the construction of the Kyiv HPP. He was the first to openly criticize the authorities, using every opportunity at any gathering.

A “museum” was operating at the construction site, displaying fossilized bones and artifacts washed out by a dredger. NAZARENKO first stored the exhibits under his bed, then in the dormitory basement. O. DOBAKHA organized a literary circle with the symbolic name “Malynovi Vytryla” (Crimson Sails), to which they invited the Sixtiers from Kyiv, including V. Zabashtansky. Lively literary discussions grew into political ones. Consequently, the party committee accused the literary circle of nationalism and disbanded it.

On June 26, 1968, O. NAZARENKO was arrested for a leaflet, “To all citizens of Kyiv,” issued for the commemoration of Taras Shevchenko on May 22. A notebook with the names and phone numbers of his friends was seized from him. Valentyn Karpenko was arrested in the same case on June 26, 1968. About 30 people were interrogated in the case (25 testified in court), including Kondriukov, who was detained twice—once for a day and another time for several days. On September 17, 1968, he was arrested and charged with conducting anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda since 1964 (Part 1 of Article 62 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR).

Kondriukov, then a second-year evening student at the Faculty of Philosophy of the Taras Shevchenko State University of Kyiv and an electrician at the experimental plant of the Ukrainian Research Institute of Superhard Materials and Tools, was accused of having handwritten in block letters the article “The State and Tasks of the Ukrainian Liberation Movement (incomplete theses for discussion)” and storing photocopies of it made by NAZARENKO; of making photocopies of the article “Regarding the Trial of Pohruzhalʼsʼkyi,” Dmytro Dontsov's book “Nationalism,” and R. Rakhmanny’s letter “To the writer Iryna Vilde and her compatriots who do not fear the truth”; of storing photographic films and prints of many documents: “Justice or Recurrences of Terror?” and “Woe from Wit” by V. Chornovil, “Report from the Beria Reserve” by V. Moroz, the document “Friends, Citizens!”; and books from foreign publications such as “A Collection in Honor of Ukrainian Scholars Destroyed by Bolshevik Moscow” and “The Great History of Ukraine from Ancient Times to 1923”; of commissioning L. Filatova to print over 100 copies of the leaflet “To all citizens of Kyiv”; of keeping anti-Soviet records; and of “slandering Soviet reality” in conversations.

KGB officers did not use physical torture on Kondriukov, but there was intimidation, nighttime interrogations, deceit, provocations, and the use of “stool pigeons.” Kondriukov demanded evidence for all accusations and only confirmed what was already known to the investigators. He avoided accusations of creating any organization and downplayed his activities. He claimed that reading forbidden literature was merely a person’s natural desire to learn something new. He did not speak about materials that were not part of the investigation, so he had few witnesses. For example, Fedir Filatov still had “Raskolnikov’s Letter to I. V. Stalin,” and Rima Motruk had a photocopy of Yuriy Klen’s “Ashes of Empires.”

Kondriukov reasoned that the literature he read and produced was indeed harmful to the current authorities, so he pleaded partially guilty. However, according to the universal concepts of a free person, he saw no guilt in his actions. On January 31, 1969, the Kyiv Regional Court (Judge Matsko, Prosecutor Khrienko) sentenced Kondriukov under Article 62, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 3 years of imprisonment in strict-regime camps. His co-defendants, O. NAZARENKO, received 5 years, and V. Karpenko, 1.5 years. Contrary to the law, witnesses who had already testified were not allowed to remain in the courtroom.

In March 1969, the Supreme Court upheld the verdict (though it reduced the court costs), even though the defense attorneys insisted on reclassifying the case under Article 187-1.

During their transport, the co-defendants were in the same “stolypin” prison wagon, but in different “compartments,” along with Valentyn MOROZ. They were struck by the death row cells at the “Kholodna Hora” prison in Kharkiv. Kondriukov served his sentence with V. Karpenko in camp ZhKh-385/3-5 in the village of Barashevo (Mordovian ASSR). He worked there as an electrician and met many interesting people. Among them were the Ukrainians Ivan Pokrovsky, Mykola Tarnavsky, Ivan HUBKA, Mykola BERESLAVSKY, and others. Levko LUKYANENKO, upon learning about the “Vyshhorod Case” in 1970, said: “And this was happening near Kyiv, right under their noses! It means our cause is not so hopeless!” After a conversation with Kondriukov, Andrei Sinyavsky remarked: “And I considered you extremists.” Kondriukov befriended the Latvian Andris Metra and socialized with Lithuanians, Armenians, Georgians, Russians, and Jews. He participated in a three-day hunger strike when a prisoner who crossed the first fence was killed.

He was released on September 17, 1971. Sometime later, he visited Oksana MESHKO and wrote down for her from memory L. LUKYANENKO's “Letter to Iryna Vilde,” which he had memorized in the camp. He helped her with household chores. He later transcribed the same letter for Ivan SVITLYCHNY and left some of his poems with him. He was interrogated about one of them, “A Downpour in the Carpathians,” in 1973 in connection with the SVITLYCHNY case.

He worked as an electrician at an auto repair plant, then at a baby carriage factory, went to Siberia for seasonal work, and worked in a special administration for anti-landslide works. Having worked 3.5 years underground, he retired in 1994 but continued to work part-time as an electrician, a watchman, and a yard keeper.

During the perestroika and glasnost eras, he did not miss a single mass gathering at the monument to T. Shevchenko, on the square near the Republican Stadium, on St. Sophia Square, or on Independence Square (Maidan Nezalezhnosti). He was a participant in the constituent assembly of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons and was a supporter of the URP (Ukrainian Republican Party). During the Orange Revolution, he brought food and clothing to the Maidan.

He lives in Kyiv. His wife, Zinaida Tarasivna Kondriukova, is a retired economist. They have two daughters: Olga Chornous (b. 1964) and Tetyana Kondriukova (b. 1974).

Bibliography:

I.

“To power—patriots-professionals!” / Samostiyna Ukraina (Independent Ukraine), No. 12-13 (276-277), 1998.

“Who is at the helm today?” / Samostiyna Ukraina, No. 26-27 (290-291), 1998.

“The complexes of Little Russian scholars” / Narodna Hazeta (The People's Newspaper), No. 22, 2001.

“A few remarks on the ‘Vyshhorod Legends’” / Chas (Time), No. 2 (102), January 25-31, 2002.

“Reflections of a former political prisoner” / Natsiya i Derzhava (Nation and State), No. 18, May 18-24, 2004.

“How the perfection of languages is compared” / Natsiya i Derzhava, No. 33, 2004.

“Has the struggle for national liberation already ended?” / Slovo Prosvity (The Word of Enlightenment), No. 21 (398), May 24-30, 2007.

II.

Chornovil, V. Tvory: U 10-y t. (Works: In 10 vols.) – Vol. 3. (“Ukrainsky Visnyk,” 1970-72) / Compiled by Valentyna Chornovil. Foreword by M. Kosiv. – Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2006. – pp. 76-78, 370, 610.

Kasianov, Heorhiy. Nezghodni: ukrainska intelihentsiia v rusi oporu 1960-80-kh rokiv (The Dissenters: Ukrainian Intelligentsia in the Resistance Movement of the 1960s–80s). – Kyiv: Lybid, 1995. – p. 84.

Danyliuk, Yu. Z., Bazhan, O. H. Opozytsiia v Ukraini (druha polovyna 50-kh – 80-i rr. XX st.) (The Opposition in Ukraine, second half of the 1950s–80s). – Kyiv: Ridnyi Krai, 2000. – pp. 37, 193-194.

KhPG Archive: Interview with O. Nazarenko on January 6 and 18, 1999, in Kyiv and January 18, 2001, in Skadovsk.

Nazarenko, Oles. “Vyshhorodski lehendy” (Vyshhorod Legends) / Chas, No. 47, 2001.

Komashkov, Volodymyr. Vyshhorod. Vybrani tvory (Vyshhorod. Selected Works) / “Museum of the Sixtiers” NGO; Compiled by O. Rohovenko, V. Chornovil; art design by H. Sevruk. – Kharkiv: Folio, 2004. – 176 p.

KhPG Archive: Autobiographical account of V. Kondriukov to V. Ovsienko dated October 21, 2006.

Memoirs of V. Kondriukov. December 2006.

V. Kondriukov’s Archive. Indictment in criminal case No. 19 against Oleksandr Terentiyovych Nazarenko, Vasyl Oleksandrovych Kondriukov, Valentyn Vasylovych Karpenko, dated December 24, 1968.

Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Vasyl Ovsienko. May 30, 2007. Corrections by V. Kondriukov on June 19, 2007.

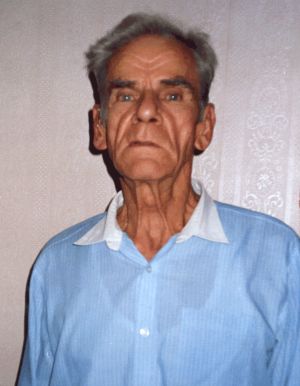

Photo by V. Ovsienko: Vasyl KONDRIUKOV. Film 2358, fr. 20. October 21, 2006.

Kondriukov Vasyl Oleksandrovych