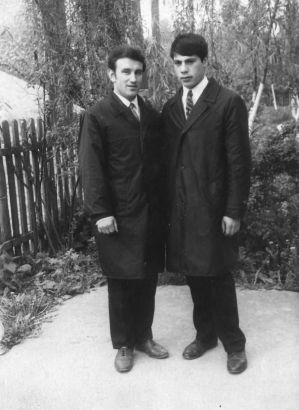

MOTRYUK, MYKOLA MYKOLAYOVYCH (b. February 20, 1949, in the village of Kazaniv, Kolomyia district, Ivano-Frankivsk region)

Founding member of the Union of Ukrainian Youth of Galicia.

Motryuk’s father, as a 17-year-old youth during World War I, was a rifleman in the Ukrainian Galician Army, and his mother was deported to Germany for forced labor during World War II. His father worked as a blacksmith on a collective farm, and so that his wife would not be harnessed into collective farm serfdom, the family moved in 1952 to the “private” mountain village of Markivka in the Kolomyia district, where there was no collective farm due to the lack of arable land. There, Motryuk, along with Dmytro Hrynkiv, finished the 8th grade in 1963. Having heard his father's stories about the struggle of the Ukrainian Galician Army, they, as underage boys, stole a small-caliber rifle from the school’s military training room, for which they were charged in 1973.

Due to poverty, Motryuk was unable to continue his education. He worked seasonal jobs in the Odesa and Zaporizhzhia regions. From 1968 to 1970, he served in a construction battalion in the Moscow region. After returning to Markivka, he worked as a mechanic at Construction Department No. 112 in Kolomyia (later PMK-67, a mobile mechanized column), from which he was laid off on March 1, 1973. He completed his secondary education at an evening school.

From a young age, he was dissatisfied with the subjugated status of the Ukrainian people. Through discussions with his school friends, the idea took shape that they must continue the struggle for independence. This was fostered by listening to and discussing foreign radio broadcasts. After the arrests of the Ukrainian intelligentsia in January 1972, specifically at a meeting in Vasyl Shovkovy’s house on January 31, the idea to create an underground organization, which took the name “Union of Ukrainian Youth of Galicia,” arose spontaneously. Also present were Dmytro Hrynkiv, Roman Chuprey, Dmytro Demydov, Vasyl Mykhaylyuk, and Fedir Mykytyuk. Placing their hands on the hilt of a knife, the young men swore allegiance to Ukraine. D. Hrynkiv was recognized as the leader of the organization. Although the organization never managed to draft a program or a charter, its goal was clear: to fight for the independence of Ukraine. The members of the UUYG considered themselves successors to the OUN but intended to achieve their goals through ideological struggle, although, depending on circumstances, they did not rule out armed struggle.

They sought out, read, and discussed literature on the history of the national liberation struggles, collected stories about the OUN and local heroes, and wrote down insurgent songs.

The UUYG was organized along the lines of UPA combat units. Each member had a pseudonym (Motryuk’s was “Lisovyk” [Forest-Dweller]). Meetings were held at someone’s home, mostly on church holidays, and sometimes in the forest, where they also practiced shooting. Motryuk, like his friends, joined a sports shooting club that operated at his workplace as part of DOSAAF, which was led by D. Hrynkiv. To record foreign radio broadcasts and their own speeches, Motryuk, along with Hrynkiv, stole a tape recorder. In the autumn of 1972, members of the UUYG laid a wreath with a blue-and-yellow ribbon at the monument to Oleksa Dovbush in Pechenizhyn to mark the anniversary of his death.

Each member of the organization was obliged to recruit new people. The idea arose to create a stamp for the organization, but the engraver they approached reported them to the KGB. After receiving warning signs, they convened a meeting specifically for the *stukach* (informer), where they simulated the organization's self-dissolution. But this only hastened the arrests.

On March 15, 1973, the KGB conducted searches at the homes of Motryuk, D. Hrynkiv, V.-I. Shovkovy, R. Chuprey, and D. Demydov. Nothing was seized during the search of Motryuk's home, but in D. Hrynkiv's briefcase, a written order for him to collect patriotic songs and stories about UPA company commander Orel, who operated in Markivka, was accidentally found. Motryuk refused to leave his house until an order was brought for his detention as a witness in the case of D. Hrynkiv.

Three days later, a KGB investigator charged Motryuk with "treason," under Article 56 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR. For three months, he was held in a solitary confinement cell in the SIZO (pre-trial detention center) in Ivano-Frankivsk and blackmailed with the death penalty or a 15-year prison sentence. The case was later reclassified under Articles 62 Part 1 (anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda), 64 (creation of an anti-Soviet organization), 140 Part 2 (theft), and 223 Part 2 (theft of a weapon).

The Ivano-Frankivsk Regional Court, in a closed session that lasted three days, delivered the verdict on August 9, 1973 (relatives were allowed in for the reading): the organization’s leader, D. Hrynkiv, was sentenced to 7 years in strict-regime camps and 3 years of exile; D. Demydov and V.-I. Shovkovy received 5 years each; and Motryuk and R. Chuprey received 4 years each.

He served his sentence in the strict-regime camp VS-389/36 in the Perm region, in the village of Kuchino, where he spent two years. He worked as a blacksmith, then in a workshop packing heating elements for electric irons with hazardous sand. He suffered from furunculosis (boils). In March 1975, with a fever, he was taken to the hospital at Vsekhsvyatskaya station, where he remained until the end of his term in zone No. 35.

He participated in the struggle for the status of a political prisoner, in the campaign to renounce Soviet citizenship, and in the production of information to be smuggled out of the zone. One letter from Motryuk, finely rewritten by V.-I. Shovkovy on capacitor paper, was seized in 1980 from Oles Shevchenko in Kyiv, about which Motryuk was interrogated at the Ivano-Frankivsk KGB. Motryuk did not confess.

In March 1977, he was brought by transport to Ivano-Frankivsk and placed under administrative surveillance for a year in Markivka, which included a ban on appearing in Pechenizhyn, through which he sometimes had to travel to work in Kolomyia, where he worked at a children's furniture factory.

From 1982 to 1985, he studied at the Kalush College of Culture and Education. In 1985, he found a job in his field, but when the head of the district's culture department, the communist Klapchuk, learned that Motryuk had been imprisoned for political reasons, he said: “Culture is the political hearth in the village; someone like you shouldn't be working here. Please, vacate the position.” After the declaration of independence, from 1991 to 1994, Motryuk worked as the artistic director of the Pechenizhyn House of Culture, but Klapchuk fired him at the first opportunity. He was unemployed.

In 1986, Motryuk was drafted via the military commissariat to participate in the Chornobyl disaster cleanup, but after Kuchma’s re-registration, he lost his status as a liquidator.

Motryuk was a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, which in 1990 became the Ukrainian Republican Party. He was a delegate to the Second Congress of the All-Ukrainian Association of Political Prisoners and the Repressed and participated in election campaigns, supporting them with concerts and speeches, and in the reburials of victims of repression in Demyaniv Laz, Yabluniv, and Pechenizhyn.

In 1991, he married Kateryna Seliverstova; they have a son, Mykola, born the same year.

He lives in the village of Pechenizhyn. He worked as a guard at a reinforced concrete plant.

By a resolution of the Supreme Court of Ukraine on July 9, 1994, the sentence was partially annulled due to the absence of the elements of a crime as provided for in Articles 62 Part 1 and 64 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR.

Bibliography:

I.

Interview with M. Motryuk, March 21, 2000, in the village of Pechenizhyn. https://museum.khpg.org/1121882723 II. *A Chronicle of Current Events*. New York: Khronika Press, 1974, issue 33, pp. 35, 36, 47, 65-66; issue 34, p. 33; 1977, issue 45, pp. 41, 50, 56; issue 47, pp. 104-106; 1978, issue 48, p. 61; issue 51, pp. 70, 93.

*The Ukrainian Human Rights Movement: Documents and Materials of the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords*. Foreword by Andriy Zvarun. Compiled by Osyp Zinkevych. “Smoloskyp” V. Symonenko Ukrainian Publishing House. Toronto—Baltimore, 1978, p. 87.

Alekseeva, Lyudmila. *Istoriya inakomysliya v SSSR. Noveishiy period* [The History of Dissent in the USSR: The Newest Period]. 1984. Vilnius–Moscow (VIMO): Vest, 1992, p. 11.

Kasyanov, Heorhiy. *Nezhodni: ukrayinska intelihentsiya v rusi oporu 1960-1980-kh rokiv* [The Dissenters: The Ukrainian Intelligentsia in the Resistance Movement of the 1960s–1980s]. Kyiv: Lybid, 1995, p. 143.

Rusnachenko, Anatoliy. *Natsionalno-vyzvolnyi rukh v Ukrayini. Seredyna 1950-kh — pochatok 1990-kh rokiv* [The National Liberation Movement in Ukraine: Mid-1950s—Early 1990s]. Kyiv: Olena Teliha Publishing House, 1998, pp. 206-208.

Danylyuk, Yuriy, and Oleh Bazhan. *Opozytsiya v Ukrayini (druha polovyna 50-kh – 80-ti rr XX st.)* [Opposition in Ukraine (Second Half of the 1950s–1980s)]. Kyiv: Ridnyi Krai, 2000, p. 38.

Hrynkiv, Dmytro. *Spohady politv’yaznya* [Memoirs of a Political Prisoner]. Ivano-Frankivsk: Misto NV, 2005, 145 pp.

*International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former USSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1.* Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny,” 2006, pp. 492–495. https://museum.khpg.org/1127939426

*Rukh oporu v Ukrayini: 1960 – 1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk* [The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960 – 1990. An Encyclopedic Guide]. Preface by Osyp Zinkevych and Oles Obertas. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010, pp. 405–406; 2nd ed.: 2012, pp. 505–506.

Vasyl Ovsienko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. May 30-31, 2003. Corrected by M. Motryuk, June 16, 2003. Last reviewed August 12, 2016.