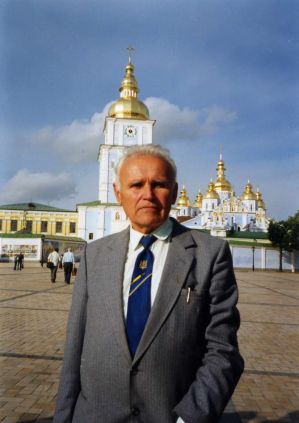

ANDRUSHKO, VOLODYMYR VASYLYOVYCH (born December 5, 1929, in the village of Sadzhavka, Nadvirna raion, Ivano-Frankivsk oblast – died October 1, 2012, in the city of Nadvirna).

A participant in the national liberation and human rights movement.

From a prosperous peasant family. His mother, Daria, was the head of the local chapter of the Union of Ukrainian Women and lived until 1967. His father was one of the organizers of “Prosvita,” was elected village headman (viyt) during the German occupation, emigrated in 1944, and died in the USA in 1971.

During the Bolshevik occupation, Andrushko and his mother were forced to abandon their home to escape persecution by the NKVD. Their house was converted into a shop and later dismantled. For a time, they lived illegally in Kolomyia. While studying at the gymnasium in 1943, Andrushko, at the suggestion of fellow student Dmytro Pavlychko, joined the OUN Youth Network. On Easter 1947, he produced his first leaflets reading, “Christ is Risen! Ukraine will Rise!” and continued to be active in the underground.

In 1948, Andrushko graduated from a secondary evening school for working youth in Kolomyia. He worked for several months as a primary school teacher in the village of Velykyi Kliuchiv, Pechenizhyn raion, but was dismissed for refusing to join the Komsomol. The following year, he taught in the village of Debeslavtsi, Kolomyia raion, where, on orders from the underground, he did join the Komsomol to avoid being fired. He hung yellow and blue flags, transported literature and weapons, distributed leaflets, burned down the Bolshevik club along with its library, destroyed a collective farm’s threshing machine, and cut telephone lines. He behaved recklessly, but the struggle became the meaning of his life. In September 1949, he nearly died during an attack by an NKVD operational group.

In 1951, Andrushko was due to be drafted into the Soviet Army. However, he managed to enroll in the Ukrainian philology department at Chernivtsi University, a long-held aspiration. There, he distributed leaflets and wrote anti-communist slogans. On March 23, 1952, Heroes' Day, the 14th anniversary of the death of OUN leader Yevhen Konovalets, he hung a national flag over the university. He fell under suspicion; it was discovered that his father was abroad, and he was expelled with a certificate stating he had completed his second year. After Stalin’s death, NKVD surveillance eased, and Andrushko managed to enroll in the third year at the Stanislav Pedagogical Institute. In 1955, Andrushko was assigned to the Pidmykhailivska secondary school in the Kalush raion.

On October 29, 1959, shortly after marrying teacher Mahda Krushelnytska, Andrushko was arrested and accused of conducting anti-communist propaganda, alleging that as a student, he had distributed underground literature. During a search, several books published during the Polish era and a few sheets of paper with notes of a “nationalist, anti-Soviet nature,” as well as a Bickford fuse and an electric detonator, were found. In March 1960, the Stanislav Regional Court sentenced Andrushko under Article 62, Part 1 (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”) and Article 222 (“possession of weapons and explosives”) to 5 years. Teacher Vasyl Protsiuk was sentenced to 4 years in the same trial. Another teacher was dismissed from his job, and one student was expelled from the institute. Not even Andrushko’s mother was allowed to attend the “open” trial.

He served his sentence in the Mordovian labor camps: ZhKh-385/3 (Barashevo), No. 7 (Sosnovka), No. 11 (Yavas), and No. 16. He was close with Levko LUKYANENKO, the Dolishniy brothers—Ivan and Yurko—and other political prisoners. The conditions in the camps worsened steadily. Andrushko participated in acts of defiance and was punished in the punitive isolation cell. He worked in a brigade that unloaded wagons of timber. To be relieved of the backbreaking labor, on the advice of a prisoner-doctor, Vasyl Karkhut, he underwent surgery for varicose veins. However, just a week later, he was assigned to another strenuous job.

In 1964, he returned to his mother and wife in the village of Kniazheluka, Dolyna raion, Ivano-Frankivsk oblast, where his wife worked as a teacher. He was denied a teaching position and worked in construction at the Dolyna oil refinery, the gas-gasoline plant, and the Kalush potassium plant. Finally, in the autumn of 1967, he managed to get a job as a Ukrainian language teacher in the Mykolaiv oblast, where he faced persecution. He moved to the Zhytomyr oblast, then to Khmelnytskyi and Lviv oblasts, but was dismissed from each job. He worked on the construction of the Yavoriv sulfur plant. He was once again fortunate to get a job at the Budaniv vocational school (Ternopil oblast). In 1980, there was an attempt to commit him to a psychiatric hospital.

He maintained contact with L. LUKYANENKO and O. MESHKO but did not join the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, hoping to remain free longer. He prepared a microfilm with materials about repressions in Ukraine to be sent to the West through a friend. His friend was denied an exit visa as a tourist, and on August 10, 1981, Andrushko himself was arrested in Kyiv while distributing leaflets. The leaflets discussed Ukraine's constitutional right to secede from the USSR. Andrushko had also hung a banner on a road sign that read: “Long live an independent Ukraine!”

At the Lenin district police station in Kyiv, KGB agents interrogated Andrushko and ordered the police to open a criminal case for attempted robbery and hooliganism. The case proceeded for two months. However, the Prosecutor’s Office of Ukraine, seeing its flimsiness, reclassified it as “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” The investigation was then taken over by the KGB investigative department of the Ternopil oblast, headed by Colonel Bidyovka. Andrushko told the investigators nothing and did not surrender the typewriter and literature he had hidden in the forest.

In March 1982, the Ternopil Regional Court sentenced him to 5 years in a strict-regime labor camp and 5 years of exile. Andrushko declined to make a final statement.

He served his sentence at camp VS-389/35, at Vsekhsvyatskaya station in the Perm oblast. Here, he had no visits. He was punished for sitting on his bed. He was sentenced to the punitive isolation cell for allegedly breaking a potato-peeling machine in the kitchen where he worked. The chemicals used for washing dishes ate away his fingernails, which have not grown back. On the other hand, he had pleasant interactions with political prisoners of various nationalities (Stepan KHMARA, Natan Sharansky, Anatoliy KORYAGIN, and others).

In the summer of 1986, Andrushko was transported to his place of exile in the Tyumen oblast, the village of Nizhnyaya Tavda, from where Semen GLUZMAN had just been released. He worked at a lumber mill, sawing wood. He lived in a rented apartment. In connection with perestroika, he was pardoned on May 5, 1987. Before his release, he visited the grave of P. Hrabovsky in Tobolsk.

He sought teaching work but was repeatedly denied employment. He appealed to the district and regional education departments and the Ministry of Education. Finally, on October 13, 1987, he published an appeal to M. Gorbachev in the journal “Ukrainian Herald,” edited by V. CHORNOVIL. Andrushko also distributed a statement to the UN Commission on Human Rights dated September 1, 1988, which was broadcast on Radio “Liberty.” A few days later, the Kolomyia district education department gave Andrushko a job in the village of Sidlyshche, Kolomyia raion.

In the winter of 1993, Andrushko exchanged his apartment and moved to the city of Nadvirna in the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast. He focused primarily on literary work (poetry, plays, essays, memoirs, and journalism). In 1998, his book of essays, “You Shall Win a Ukrainian State…,” was published in Nadvirna, which had already been partially published abroad. His play “Foolish Children” was staged at the People's House in Chernivtsi. His plays were also staged in the Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil regions, and in Australia, which he visited at the invitation of the Ukrainian diaspora. He was on the editorial board of the journal “Our Goal” (Adelaide). At the invitation of his countrymen, he visited Great Britain, Germany, and Belgium several times.

His daughter, Lesia, works as a teacher.

Bibliography:

I.

Zdobudesh Ukrainsku derzhavu... (You Shall Win a Ukrainian State...). Nadvirna, 1998. 132 pp.

KHPG Archives: Interview with V. Andrushko, July 18, 2000. https://museum.khpg.org/1120844260

Kryvavyi zasiv (The Bloody Sowing). Nadvirna, 2005. 96 pp. (A collection of dramatic works).

II.

Visnyk represii v Ukraini (Herald of Repressions in Ukraine). Foreign Representation of the UHG. Ed. and comp. by N. Svitlychna. New York. 1980–1985. 1982: 10-1.

Mizhnarodnyi biohrafichnyi slovnyk dysydentiv krain Tsentralnoi ta Skhidnoi Yevropy i kolyshnoho SRSR (International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former USSR). Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1. Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny,” 2006. Pp. 33-36. https://museum.khpg.org/1127937299

Roman Hladysh. “Volodymyr Andrushko: Khochu zustrity smert u chyni ukrainskoho natsionalista” (Volodymyr Andrushko: I Want to Meet Death in the Rank of a Ukrainian Nationalist). Halychyna, July 25, 2009. http://www.galychyna.if.ua/publication/society/volodimir-andrushko-khochu-zustriti-smert-u-chini-ukrajin/.

Liubov Kafanova. “Sydiv z Lukianenkom…” (He Was Imprisoned with Lukyanenko…). October 16, 2009. http://versii.cv.ua/osobystosti/volodymyr-andrushko-sydiv-z-lukyanenkom-stusom-tishyt-te-scho-nalezhav-do-ostannih-politvyazniv/6127.html

Rukh oporu v Ukraini: 1960 – 1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk (The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960 – 1990. An Encyclopedic Guide). Preface by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010. Pp. 52-53; 2nd ed. – 2012. – Pp. 58-59.

Entsyklopediia suchasnoi Ukrainy (Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine), Vol. 1. Kyiv, 2001. P. 512.

Vasyl Ovsienko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. September 28, 2005. Last read on August 2, 2016.