(born January 15, 1915, in the village of Mayachka, Kobeliaky raion, Poltava oblast – died January 22, 2009, in Kyiv)

From a family of farmers, once Cossacks. His grandfather, Fedosiy Kyrylovych Karpenko, was a teacher and owned a rare library; under the Central Rada, he headed the Kobeliaky county government. His father, Benedykt Andriyovych Brovko, served in the navy in Vladivostok, returned home in 1928, and began farming his 5 hectares of land, but refused to join the kolkhoz (collective farm) when forced collectivization began. In response, his farm was looted by party "activists." In 1933, his father decided to return to the navy, but was detained by the GPU en route and disappeared without a trace. His mother, Nataliia Fedosiivna Karpenko, was forced to join the kolkhoz. She died in 1977 in Kyiv.

In 1930, B. completed 7 grades in Mayachka and entered the Kharkiv Medical Technical School, but was expelled after six months as the son of a serednyak (middle peasant). In 1931, he enrolled in a pedagogical technical school in the city of Chervonohrad in the Kharkiv region. But in the hungry autumn of 1932, he had to leave his studies and return home.

In January 1933, B. was appointed a teacher at a seven-year school in the village of Rudky, Tsarychanka raion. In May 1933, a student named Mariyka Khailo died of starvation during his class. This shocked the 17-year-old teacher, who accused the authorities of creating an artificial famine and the school director, Lebid, of the student's death. That evening, a colleague informed B. that the director had called the district GPU about his behavior. That same evening, B. fled from Rudky back home.

In the summer of 1933, B. found a job as a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature at a seven-year school in the village of Kokhanivka, Sakhnovshchyna raion, Kharkiv oblast. In May 1934, the houses left empty after the famine were settled by people from the Sverdlovsk oblast. On these grounds, the school began to switch to Russian as the language of instruction. B. expressed his dissatisfaction. The school director, Leheza, fired him but did not report him to the GPU. B. then found a teaching job in the village of Rai-Horodok, Sloviansk raion, Stalin (now Donetsk) oblast.

In 1939, B. graduated by correspondence from the philology faculty of the Donetsk Institute of Public Education in Luhansk. That same year, he was drafted into the Red Army. He served in the city of Kolomna near Moscow in a heavy artillery regiment. He participated in the “liberation campaign” in Western Belarus (Hrodna) and Western Ukraine (Volyn). In the winter of 1939-40, his regiment took part in the Winter War, including the breaching of the Mannerheim Line.

In early January 1945, during the Warsaw Uprising, which the Soviet Army did not support, Major B., chief of staff of the third army group of Guards mortar units (“Katyushas”), discovered a private Ukrainian library in an abandoned house in Praga, a suburb of Warsaw where the headquarters was stationed. Seeing Warsaw being destroyed by German bombers and artillery, he decided to take several dozen Ukrainian books, which he later brought to Ukraine. These included books by P. Kulish, M. Hrushevsky, S. Yefremov, S. Rusova, B. Hrinchenko, M. Vozniak, M. Drahomanov, and the 16-volume “Kobzar” by T. Shevchenko.

At that time, in a conversation with his friend, Colonel Georgy Tyulin, chief of staff of the “Katyushas” on the Belarusian Front, B., a member of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), spoke very negatively about Stalin. Tyulin listened and said, “I have a different opinion of Stalin. There should be no more such conversations between us.”

Through the efforts of G. Tyulin, in May 1945, B. was included in the special group “Postril” (Shot), which studied and restored captured German V-2 rockets at the RABE institute (“Raketenbau,” Bleicherode, Thuringia). The group was led by Sergei Korolev, the outstanding designer of rocket and space technology. On October 18, 1947, B., as commander of the launch division, participated in the launch of the first ballistic missile from the Kapustin Yar test site (Astrakhan oblast, RF). His name, Major B., is inscribed on an obelisk erected there to commemorate the event.

In 1948, B. retired from the military and began teaching the “unpromising” subjects of Ukrainian language and literature in Pushcha-Vodytsia near Kyiv. In 1953, he completed his postgraduate studies at the Research Institute of Pedagogy and taught Ukrainian literature at Kyiv’s Taras Shevchenko University. In 1957, he defended his PhD dissertation on the topic “Studying the Works of Oles Honchar in School,” and a book of the same name was published that year. In the spring of 1960, Associate Professor B. received an apartment in Kyiv and had a doctoral dissertation ready for defense on the topic “Methodology of Literature (History, Theory, Normative Course).” He was offered the headship of the pedagogy department at Kyiv State University, where he was already working as an associate professor of pedagogy.

Meanwhile, B. maintained friendly relations with the Sixtiers, especially with Yevhen SVERSTIUK, whom he sheltered in his home in Pushcha-Vodytsia in 1959. The KGB secretly bugged their conversations, and when B. reacted to the news of S. Bandera’s murder by saying, “It was them, the bastards, who killed him,” surveillance intensified.

It turned out that Associate Professor B., while teaching a course on pedagogy, took the liberty of quoting not only Marx and Lenin but also Hrushevsky; not only Gorky but also Vynnychenko; he supported purely pedagogical statements with both Makarenko and Sofiya Rusova and explained specific psychological phenomena according to Freud. His books, brought from Poland, were used by the Sixtiers and read by students.

In the spring of 1960, the Minister of Higher Education, Dadenkov, sent B. to Chernivtsi as part of a commission to inspect the local university. Meanwhile, a secret search was conducted at his home. His mother was also searched at the train station in Poltava. Upon returning from Chernivtsi, B. was detained by KGB agents in Kyiv, taken home, and presented with a warrant to search his apartment. Everything of value from the books collected over nearly a century, first by his grandfather and father, was transferred to a car within an hour and sent, along with their owner, to the KGB at 33 Volodymyrska Street. There, he was presented with the standard accusation: “slander against Leninist national policy and anti-Soviet activity.” Interrogations, threats, and promises lasted for almost a week. The culmination was a meeting with General Shulzhenko, deputy chairman of the republican KGB: “Tell me, how did you come to take a nationalist path?” B. replied: “I am following the path that my grandfather and father followed—it is the working path of a Ukrainian.” The general interrupted: “The only correct path is the Leninist path, and as a communist, you should know this! If you don't come to your senses, you will fare poorly on that path.” According to the general, B. avoided arrest only thanks to the intervention of his Moscow friends in the field of cosmonautics, who had already become generals and ministers.

That day, May 30, 1960, B. was released, and the next day he was summoned to the university for a party bureau meeting. The party bureau secretary accused B. of quoting, as he put it, “the vilest enemy of the Ukrainian people, Hrushevsky,” during lectures and proposed to expel B. from the CPSU and dismiss him from his job. His colleagues unanimously voted “for” and scurried away like mice. Expelled, humiliated, and branded, B. left the university. In Taras Shevchenko Park, a young man approached him, hugged him, and said, “Ivan Benedyktovych, hold on, we love you, thank you for all the good things you have given us.” It was a student, the poet Volodymyr Pidpalyi.

The next day, May 31, 1960, Borys ANTONENKO-DAVYDOVYCH summoned B. to his place. A conversation took place about the persecution of the Ukrainian intelligentsia (Dean of the Faculty of Journalism Associate Professor Matviy Shestopal, Professor of Chemistry Andriy Holub, Professor of Mathematics Ostap Parasiuk). After this meeting, they maintained a friendly relationship. For example, B. drove B. ANTONENKO-DAVYDOVYCH and the sculptor and ethnographer Ivan HONCHAR in his car to Poltava, to the Sorochyntsi Fair, to Stari Sanzhary, to Uman to visit Nadiya SUROVTSOVA, and to Kaniv to the grave of Taras Shevchenko. On August 8, 1969, the 150th anniversary of P. Kulish's birth, B., along with B. ANTONENKO-DAVYDOVYCH, Y. SVERSTIUK, and I. DZIUBA, traveled to Motronivka and Baturyn. In March 1980, B. met V. STUS at B. ANTONENKO-DAVYDOVYCH’s apartment, and earlier, Heliy SNIEHIROV.

After nearly two years of unemployment, in 1962, B. was allowed to work as an associate professor of psychology at the Nizhyn Pedagogical Institute. It was he who brought the work by I. DZIUBA, “Internationalism or Russification?,” to Nizhyn, from where Professor Hryhoriy Avrakhov passed it to Mykola Mushynka in Bratislava, who was then arrested with it.

From 1972, B. was the pro-rector of the Kyiv Institute of Culture. He retired in 1975. He maintained friendly relations with the families of political prisoners and collected funds to support them and their families.

In 1989, Oksana Meshko involved B. in the work of the Ukrainian Committee “Helsinki-90,” established on June 16, of which he was a co-chairman. In October 1990, as part of a UKH-90 delegation, he participated in the work of the Helsinki Citizens' Assembly in Prague.

He is the author of works on pedagogy and literary studies, a book about S. Korolev titled "Space Is Poor Without Poets," and numerous articles and interviews. He lectures and promotes knowledge about the development of cosmonautics and the history of the human rights movement. He was awarded medals named after Y. V. Kondratyuk and S. P. Korolev, the “Veteran of Russian Cosmonautics” badge, and is an honorary citizen of the Novy Sanzhary region.

His book “A Heart Warmed by Goodness,” and the film by director Oleksandr Ryabokrys “Ivan Brovko: Lessons of Historical Truth” leave us his truthful testimony about the Holodomor, the war, the participation of Ukrainians in the conquest of space, and most importantly, the bright image of a true Ukrainian intellectual, Ivan Benedyktovych Brovko.

Bibliography:

I.

Brovko, I. B. Vyvchennia tvorchosti Olesia Honchara v shkoli (Studying the Works of Oles Honchar in School). Kyiv: Radianska shkola, 1957. 120 pp.

Brovko, I. B., Kotsiubynska, M. Kh., Sydorenko, H. K. Analiz literaturnoho tvoru. Posibnyk dlia vchyteliv (Analysis of a Literary Work: A Teacher's Guide). Kyiv: Radianska shkola, 1959. 68 pp.

Brovko, I. B. Kosmos beden bez poetov... (Space Is Poor Without Poets...). Kyiv: “Znanie” Society of the UkrSSR, 1986. 46 pp.

II.

Dobrom nahrite sertse. Do 80-littia Ivana Benedyktovycha Brovka (A Heart Warmed by Goodness: For the 80th Birthday of Ivan Benedyktovych Brovko). Compiled by V. Ovsienko. Kyiv: Ukrainian Republican Party, 1995. 64 pp.

Kapliy, Svetlana. “Ivan Brovko, s kotorogo nachinayetsya kosmos” (Ivan Brovko, from Whom Space Begins). Vseukrainskiye vedomosti. 1998, No. 34 (928). February 21. Pp. 6-7.

Bobryshchev, Kostyantyn. “Ivan Brovko.” In Bobryshchev, Kostyantyn. Otchyi krai (Fatherland). Poltava: Dyvosvit, 2002. Pp. 74-83.

Vasylashko, Vasyl. “Uvichnenyi i hnanyi” (Immortalized and Persecuted). Kyiv. 2004. No. 4-5. Pp. 134-138.

Sverstiuk, Yevhen. “My vybyraly zhyttia” (We Chose Life), Interview 1995–1999. In Bogumiła Berdychowska, Olya Hnatiuk. Bunt pokolinnia. Rozmovy z ukrainskymy intelektualamy (Rebellion of a Generation: Conversations with Ukrainian Intellectuals). Kyiv: Dukh i litera, 2004. Pp. 66-71.

Shudria, M. A. “Brovko Ivan Benedyktovych.” Entsyklopediia suchasnoi Ukrainy (Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine). Vol. 3. Kyiv, 2004. P. 470.

Dobrom nahrite sertse. Do 90-richchia I. B. Brovka (A Heart Warmed by Goodness: For the 90th Anniversary of I. B. Brovko). Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; art design by B. Zakharov, ed. V. Ovsienko. Kharkiv: Folio, 2005. 136 pp. with photo illustrations (From his interview “To Preserve the Human Being Within Oneself,” pp. 3 – 39);

Mizhnarodnyi biohrafichnyi slovnyk dysydentiv krain Tsentralnoi ta Skhidnoi Yevropy i kolyshnoho SRSR (International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former USSR). Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1. Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny,” 2006. Pp. 82–86. https://museum.khpg.org/1120945936;

Rukh oporu v Ukraini: 1960 – 1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk (The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960 – 1990. An Encyclopedic Guide). Preface by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010. Pp. 89–90; 2nd ed.: 2012. Pp. 99–100.

Vasyl Ovsienko. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. February 8, 2005. Last read on August 2, 2016.

Photos:

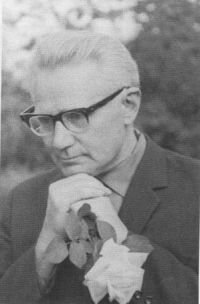

Brovko I.B. Brovko, pro-rector of the Kyiv Institute of Culture. 1972.

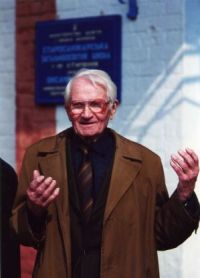

Brovko1 I.B. Brovko on February 22, 2002, speaking in the village of Stari Sanzhary in the Poltava region at the ceremony naming the local school after Oksana Meshko.