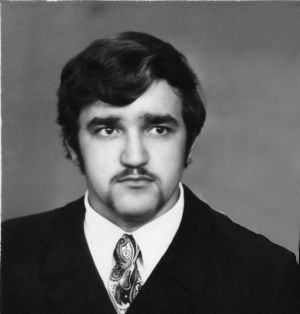

(born May 8, 1955, in Stebnyk, Drohobych raion, Lviv oblast).

Participant in the independence movement of the 1970s - 90s.

From a nationally conscious family: his grandfather, lawyer Volodymyr Starosolskyi (1878–1942), defended Vasyl Bilas and Dmytro Danylyshyn in court (1932), participated in the defense of Stepan Bandera (1934), and died in Siberia. Virtually all his relatives were repressed. His father, Zenoviy Starosolskyi (1933–1986), was a worker, and his mother, Oksana Mykolayivna Holovko (b. 1935), was a nurse.

In 1971, as a 16-year-old 10th-grade student at School No. 7, Starosolskyi and his friends created a nationalist group (of up to 30 people) to fight for the independence of Ukraine. The group was led by Roman KALAPACH, who was a year older. The young men's primary goal was to obtain higher education, but they were already eager to act.

During a meeting at Mykhailo Kulyk’s home, R. KALAPACH proposed raising yellow-and-blue flags over Stebnyk on May 1 to show that there were still people fighting for an independent Ukraine. He bought yellow fabric in Lviv with money from Zinoviy Dmytriv. Since blue fabric was nowhere to be found, on May 6, 1972, Starosolskyi suggested taking down the flags of the Ukrainian SSR to use the blue part for a Ukrainian flag, but they were unsuccessful. On the night of May 7, R. KALAPACH and Z. Dmytriv managed to tear down two flags. On the night of May 9, Starosolskyi, R. KALAPACH, with the participation of Petro Yaruniv, hand-sewed two flags. That same night, KALAPACH and Starosolskyi hung them—one on the balcony of the “Shakhtar” House of Culture, and the other on a flowerbed in the city center, after removing the USSR flag from its flagpole (which they threw into the river). They wrapped the flagpole with thin copper wire so that it would fit tightly into the pipe.

The director of the House of Culture saw the flag in the morning, took it down, hid it under a podium, but did not report it anywhere. The second flag, however, flew until 2 p.m.: KGB agents and police arrived but were afraid it was mined and waited for sappers. Many people came to look at the flag.

The local KGB agent, Vasyl Zaderey, could not identify the daredevils. A special investigation team from Kyiv, led by KGB Major Kharitonov, then checked all 450 former political prisoners living in Stebnyk, questioning where each one was and what they were doing at the time, but could not find the culprits. The case gained wide publicity. A meeting was convened at the House of Culture, urging people to identify the “criminals.” Only then did the director produce the flag from under the podium…

Meanwhile, a member of the youth group, Volodymyr Pikas, forgot a notebook at school with a list of frequencies for the radio stations “Radio Liberty,” “Deutsche Welle,” and “Voice of America.” The school director, Isaak Kamsa, took the notebook to the KGB. Suspicion fell on the students. Starosolskyi, a winner of mathematics Olympiads, an excellent student, and secretary of the school’s Komsomol organization, and Mykhailo Kulyk were given failing grades for conduct, barred from their final exams, and expelled from school. Only two teachers were against it.

To divert suspicion from Starosolskyi and Kulyk, in August 1972, R. KALAPACH, who was already taking exams for the law faculty of Lviv University, wanted to organize the posting of leaflets in Stebnyk and Drohobych, but one of the group members mentioned this plan to his father. The father exposed the entire group in exchange for the release of his other son from criminal imprisonment. The young men began to be summoned for questioning by the KGB. Starosolskyi was interrogated for 27 hours continuously. Having achieved nothing, they released him on his own recognizance. Believing that the young men were being directed by someone older, they decided to watch them. Meanwhile, Starosolskyi got a job as a worker at “Stebnykprombud” and was already psychologically prepared for arrest.

On February 9, 1973, Starosolskyi and R. KALAPACH were arrested. They were threatened with psychiatric confinement.

At a closed session of the judicial collegium of the Lviv Regional Court, held on February 18–19, 1973, prosecutor B.I. Kolomiyets demanded a sentence of 6 years in strict-regime camps for R. KALAPACH and 5 years for Starosolskyi under Article 62, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”), as well as under Article 187-2 (“desecration of a state flag”). Lawyer Maria Polishchuk argued that minors could not be sentenced to more than three years and that Starosolskyi, who was not even 18 at the time of the trial, could not be assigned to a strict regime, as stipulated by Article 62, Part 1. The court, presided over by I.Yu. Khomko, sentenced R. KALAPACH to 3 years in a strict-regime camp and Starosolskyi to 2 years in a general-regime camp, as well as 1 year for each under Article 187-2. Other members of the youth group (Zinoviy Dmytriv, Petro Yaruniv, Mykhailo Kulyk) were treated as witnesses in the case and released into the custody of “labor collectives.”

Starosolskyi was held in the pre-trial detention center until he came of age. In May, the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR brought the sentence into line with the “world’s most humane” Soviet law: it changed the regime from general to strict. Starosolskyi was not given a copy of the amended verdict; it was only read to him in his cell.

During transport, Starosolskyi met Zorian POPADIUK and Yaromyr MYKYTKO, who were convicted for creating the “Ukrainian National Liberation Front,” as well as members of an underground group, Petro VYNNYCHUK and Mykola SLOBODYAN—the latter had also raised flags with other youths in the city of Chortkiv.

Starosolskyi served his sentence in camp ZhKh-385/19 in the village of Lesnoy, Zubovo-Polyansky raion, Mordovia. He worked in a mechanical workshop processing wooden parts for wall clocks. The Ukrainian community, as well as groups of Lithuanians, Jews, Armenians, Romanians, and Russian democrats, warmly welcomed the youngest political prisoner. He communicated with insurgents Dmytro Syniak, Roman Semeniuk, Mykola Konchakivskyi, Mykhailo Zhurakivskyi, Ivan Myron, and Father Denys Lukashevych. When Starosolskyi finished the 10th grade of evening school in the camp, they held a graduation party for him. Starosolskyi participated in protest actions on October 30 (Political Prisoner’s Day) and December 10 (Human Rights Day).

Starosolskyi was released on February 9, 1975, at Potma station, but a warrant officer accompanied him to Moscow and put him on a train to Truskavets.

In Stebnyk, Starosolskyi was immediately placed under administrative supervision for a year. He got a job as a carpenter. For appearing at the House of Culture and on a fabricated charge of insulting a police officer, he was sentenced to have 25% of his earnings deducted for six months.

He decided to enroll in a correspondence course at an institute that same year. He received permission from the police to travel to Kharkiv for entrance exams but actually enrolled in the mathematics faculty of Simferopol University. He kept his place of study secret for three years. He was a successful student, so one day in 1978, while returning from a session, the police in Lviv, where he was already working, checked his documents, including his grade book. He was ordered to get out of Lviv. Two weeks later, he was expelled from the university for “academic arrears” that did not exist. Starosolskyi later found out that a satisfactory grade had been changed to unsatisfactory.

Meanwhile, Starosolskyi joined a circle of surviving and released human rights activists (Lyubomyra Popadiuk, Olena ANTONIV, Atena Pashko, Stefania SHABATURA; Borys ANTONENKO-DAVYDOVYCH would visit from Kyiv), who exchanged information and collected and distributed aid to the families of political prisoners. Some Galicians who received packages from relatives abroad sold the items and donated the money for such assistance. Starosolskyi delivered this money to elderly and infirm former political prisoners and to families of political prisoners who needed to travel for visits or send packages. The KGB suspected Starosolskyi's activities and decided to stop them.

An engineer, Mykola Vozniak, asked Starosolskyi to sell several radio-cassette players and donate part of the proceeds to these humanitarian causes. Starosolskyi took the players to a commission store. But they turned out to be stolen. On March 28, 1979, he was arrested and, two weeks later, sentenced on charges of “theft of state property” (Article 81, Part 2) to 6 years in a strict-regime camp. M. Vozniak was sentenced to 6 years in a reinforced-regime camp, but Vozniak never served any time. The director of the commission store, who had helped raise funds for political prisoners, later received a 4-year sentence.

Starosolskyi served two years in colony No. 30, and from the spring of 1981, in colony No. 48 in Lviv. There were hunger riots in the camps because rations were cut and spoiled food was supplied. As an experienced prisoner, Starosolskyi had no conflicts with his environment.

When Z. POPADIUK was arrested in Kazakhstan on September 2, 1982, an investigator offered Starosolskyi a chance to testify against him in exchange for a lighter sentence. Starosolskyi flatly refused.

Having served half his term, Starosolskyi, as someone with no regime violations, was "conditionally released" by a court—transferred to a “khimiya” assignment (a form of conditional release involving manual labor) in Novyi Rozdil. The conditions there were unbearable. Starosolskyi lasted 3 months. To avoid a criminal provocation, he deliberately left his place of punishment and hid for 45 days, wandering. He spent most of his time in the Lviv oblast and also visited Kyiv.

Out of desperation, he returned to the “khimiya,” from where a court sent him back to camp No. 48, adding 45 days to his sentence.

He was released on May 19, 1985. He lived in Stebnyk and was under administrative supervision for 1 year: he had to be home from 7 p.m. to 6 a.m. Certain public places in the city were off-limits to him. Every week, he had to sign in with the police. He worked in construction. When his crew traveled by bus to work in Truskavets, Boryslav, or Drohobych, Starosolskyi was not allowed to leave the worksite.

In 1985, through Z. POPADIUK’s grandmother, Sofia Kopystynska, he met a girl who was helping her at the time, Anzhela Sankauskaitė, from a repressed family of a Lithuanian and a Ukrainian. They married and have three daughters: Mariana (b. 1986), Zoryana (b. 1988), and Marusynka (b. 1997). He finished building the house that his father had started.

During the perestroika era, Starosolskyi participated in the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union in the Lviv region, and later the Ukrainian Republican Party. He was a member of propaganda "mobile groups" to Eastern Ukraine. From 1990-95, he was the regional organizational officer of the OUN (Melnyk Faction), which was re-established in Ukraine as an all-Ukrainian public organization.

In 1992, a memorial sign was unveiled in the center of Stebnyk with the inscription: “Here on May 9, 1972, the national flag was raised.” Starosolskyi did not agree to have his name on it.

Due to the closure of the “Polimineral” Potash Plant, there was mass unemployment in the city. In 1995, Starosolskyi had to go to the Czech Republic for work, and later to Lithuania and Poland. In late 1996, he led an initiative group that sought justice in the supply and payment of gas in Stebnyk and Drohobych, taking the case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. To protect the economic interests of the people, he ran for mayor in March 1998. Old Stebnyk voted for Starosolskyi, but New Stebnyk, i.e., the workers brought from Russia for the plant, voted against him. He received 4,000 votes (second place).

He worked in construction and was occasionally unemployed. He moved with his family to Lithuania.

Bibliography:

Visnyk represiy v Ukrayini. Foreign Representation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. Editor-compiler N. Svitlychna. New York. 1980 – 1985. – 1981: 3, 4, 5; 1982: 3-29; 1985: 3-32, 9-23.

Kasyanov, Heorhiy. Nezhodni: ukrayinska intelihentsiya v rusi oporu 1960-80-kh rokiv – Kyiv: Lybid, 1995. – p. 142.

Stus, Vasyl. Tvory. Vol. 6, Book II. Lviv: Prosvita, 1997. – pp. 115, 213.

Pastukh, Roman. Stebnytski lomykameni // Drohobychchyna – zemlia Ivana Franka. – Drohobych: “Vidrodzhennia” Publishing Firm, 1997. – pp. 83, 417 – 418.

Interview with L. Starosolskyi and his mother Oksana Holovko from January 28, 2000. https://museum.khpg.org/1195846812

International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe and the former USSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 2. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava liudyny,” 2006. – pp. 736–739. https://museum.khpg.org/1120814542

Rukh oporu v Ukrayini: 1960 – 1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk / Preface by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. – Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010. – pp. 621–622; 2nd ed.: 2012, – pp. 705–706.

Vasyl Ovsiyenko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. March 22, 2004. With corrections by L.S. Last read July 24, 2016.