Zhytomyr

“Ruta” Publishing House

2016

Down the Road of Absurdity

This story is for those who have managed, at least for a moment, to rise above themselves, like a fish out of water.

—The Author

It has been a very long time since I was cast down from Olympus. I descend lower and lower—of the great bonfire that snatched all surroundings from the darkness, only smoldering embers remain.

No, I have not become a happy Sisyphus, for there is still the memory of my time on the summit, of the sentence to absurdity. But I have descended to the people so closely that I have undertaken to write to people. To whom else?! Not to the trees in the forest, though what difference is there between them—only that people can move. (Perhaps I have indeed become a little infected, since I’ve taken to writing).

Life is a continuous current. My story about life will also be continuous.

I don’t remember, but according to my birth certificate, I was born on December 13 (“on St. Andrew's Day.” They were going to name me Andriy, but Grandma Nastya was against it—probably because of some other Andriy) in the village of Rohachiv, Baranivka Raion, Zhytomyr Oblast. Like everyone, I came into this world not of my own will—it was the will of nature, or perhaps of God. And I don’t remember how I perceived this world, my appearance in it: with protest or acceptance—whether I screamed, cried, or laughed. I only know from my father's story that when I was being baptized, the godfather—my father's brother Oleksandr—had to hold my hands because I was slapping the priest in the face. And why I was slapping him—I don’t remember that either. Perhaps that priest was a great sinner, or perhaps I didn't want to accept baptism.

My parents: my father, Babych, Oleksa Savych, from Rohachiv. When the first “Babych”—Hnat Babych with his wife Olena—appeared in Rohachiv and where he came from is unknown. It is only known that Hnat Babych, who started the Babych line in the village, had six children; that his eldest son, Fylip, married in 1804 at the age of 21; that Hnat’s son Tereshko (Terentiy) lived on a khutir (a farmstead; his house stood behind the church, 350 meters from the highway, then a dirt road from Baranivka to Zvyahil). That over time, other peasants also began to build houses there, and thus, a street named “Tereshkova” after my great-great-grandfather appeared in the village. Tereshko's house stood on the left side of the street. His son Lukyan also lived on Tereshko's homestead. And Lukyan passed it on to his son Sava, my paternal grandfather.

Hnat’s sons—Fylip, Mykhailo, and Tereshko—were serfs, as evidenced by the parish registers of the 1830s and 40s. When they were enserfed is unknown.

The surname “Babych” appeared long ago. In the 15th century, five princes (brothers) had the surname “Babych.” (Their father, who died in 1436, was “Baba”). They were the Hiedyminid (Olherdovych) princes: the Drutsky family (N.M. Yakovenko, “Ukrainian Gentry”). This surname is quite common. In 1962, when I was imprisoned in Camp No. 7, I met a Cossack from Kuban with the surname “Babych.” He told me that during the war, his military unit was stationed in a Yugoslav village. It turned out that most of the residents of that village had the surname “Babych.” When they learned that he too was a “Babych,” they began to treat him, taking him from house to house and assuring him that he was their distant relative.

My grandfather Sava (who died in the mid-1930s) married a Polish woman, Nastya Yagelska from the village of Klymental, in 1901. Sava was 20, and Nastya was 17. By that time, Nastya was already Orthodox. In addition to my father, Oleksa (1904-1985), they had Oleksandr (1902-1961), Natalka (in the parish register Pelahia, 1908-1974), and Maria (who died of gangrene in the 1930s before reaching adulthood).

Sometime in the late 1920s, my father married Olena Holub. They had two sons—Vasyl (1928-2006) and Pavlo (1930-2002). In the early 1930s, the family fell apart. Vasyl stayed with his father (living with us until he was 16), and Pavlo with his mother. After the war, his mother gave them the surname of her second husband, who died at the front—Zavalnyuk. She did this to receive some, albeit meager, government assistance for her sons. (That assistance did not save Vasyl from prison. In the post-war hungry years, Vasyl had to serve time in prison for a basket of potatoes from the collective farm field). Why did the family fall apart? It is only known that it was due to constant quarrels (Olena associated with members of the Komnezam, the Committee of Poor Peasants). Due to the family conflict, my father even had to spend about six months in the Zhytomyr prison. After a fire occurred (there was suspicion that someone had set the house on fire), he and his parents left Tereshkova street, building a house near the swamp, about halfway between Prapor and the Kykivsky poselok (settlement), which appeared later, before the war. (Incidentally, the Honcharuks later built on Tereshko's homestead. While digging a pit for a root cellar, they found a stone hammer and a sharp flint knife). In 1934 or 1935, my father married my mother, Pavlyuk, Maria Lukashivna (Lukivna) from the village of Kykiv, who at that time lived on a khutir next to the later-formed Kykivsky poselok (now called “Ukrainske” (?!), as if the surrounding villages were not Ukrainian). The family was enserfed—forced into a collective farm.

By the beginning of the 19th century, the Pavlyuk family in the village of Kykiv was quite numerous. In some parish registers, it is indicated that certain Pavlyuks belonged to a certain landlord. From this, we can conclude that all the Pavlyuks in the village of Kykiv were enserfed. This is also somewhat confirmed by what remained in my mother's memory from recollections of those old times.

The maternal lineage could only be traced back to my great-grandfather Mosiy (Moisey), who died in 1907 at the age of 65, and his wife Paraska, who in 1887 had my maternal grandfather Lukash (Luka).

In 1906, Lukash married Yavdokha Tymoshenko. Both were 19 years old. They had: Sozont (b. 1907—was alive in 1928. His fate is unknown), Maria (1912-1989—my mother), Kindrat (1919-2003), Hanna—my godmother (1922-1983), Vasyl (1923-1942—died in the Oryol Oblast in the village of Zheleznivka), Maksym (1928-1977), Oleksa (b. 1930), and Khrystia (1932-1933).

Grandfather Lukash, Grandmother Yavdokha, and their older children were very good singers. Young people constantly gathered at Grandfather Lukash’s khutir. Grandfather Lukash played the sopilka (a Ukrainian flute) and beat the bubon (a tambourine), both of which he made himself. The youth danced and sang. Those were the 1920s. That was all the joy there was in my mother's life. (From the memories of my uncle Oleksa about Grandmother Yavdokha and Grandfather Lukash: I was with my mother in the field. She was harvesting flax, sweating, and then it started to rain. My mother caught a cold and fell ill. A large swelling appeared around her neck. Father took her to the hospital in Novohrad, but it didn't help. She died in '33 or '34. When they were making her coffin, and it was summer, I was playing with scraps of boards. I also remember us, sitting on the stove, banging our heads against it out of hunger and screaming “I want to eat!” My sister Khrystia was lying in the cradle, also crying from hunger. And Mother lay motionless in bed. Around that time, Khrystia died. It must have been '33. And Father died in '44 on the feast of John the Baptist... I was sitting by the stove in a greatcoat and a Budyonovka hat. That was when the Germans were retreating. German soldiers came into the house. Seeing me, a soldier immediately pointed his rifle at me and shouted: “Partisan!” Father grabbed the rifle and pushed the barrel aside, exclaiming: “Small! Small! A child!” and began to undress me. The soldiers left, but my father was very distressed. Soon after, one evening, he went outside. He wasn't there for long. He came back into the house, lay down, exhaled strangely a few times, and he was gone. It must have been a heart attack).

My mother's first husband was Naum Rybak, from the village of Kykiv. They lived on a khutir on the left side of the highway outside Kykiv. They had a son, Ivan. In 1933—the famine. The son, husband, and father-in-law die of starvation. Mother lies swollen in the house—already awaiting the end. But her father, Lukash, comes and takes her to his place. This saved Mother from death. And starvation had wiped out many then. (Miraculously, a list of those who died in 1933 in the neighboring village of Kyyanka has survived and is in the regional archive. In this small village, from January 6 to December 29, 1933, 199 people of all ages died.) Mother rarely spoke of that famine. Probably because she always had to think about how to survive, how to feed her children. Periodically, I would hear her talk about Mykhalko (Naum's younger brother), who lived in the village of Kanuny. Mother, being at the market in Novohrad-Volynskyi, would accidentally meet him and tell us about it at home.

So, after my release in the 90s, I began to think that I should go to the village of Kanuny and see that Mykhalko with whom my mother used to talk. One day, while waiting for a bus in Novohrad, I started a conversation with some young women. It turned out they were from Kanuny. I asked about Mykhailo. "There is such a person," they told me. To be honest, I hardly hoped he was still alive, as it was already the summer of 1998. I decided: I must go immediately.

Having arranged a trip with Uncle Kindrat, I drive to Novohrad, pick him up, and after visiting our relatives' graves at the Kykiv cemetery, we turn towards Kanuny. We enter the village. His house is right after the small bridge. We go inside. Mykhailo is lying in bed. He is in such a state that he cannot even get up. Approaching him, I say:

—“I am the son of Maria, with whom your brother Naum lived.”

—“What! Are you not dead? You’re alive?!” Mykhailo says in astonishment. For some reason, he thought I was that little Ivan from '33.

In 1939, due to the liquidation of the khutir system, my parents moved their house and barn to the village of Rohachiv, building on Smoldyriv road, on the right side, at the exit of the village.

My parents had six of us children: Nadia (1936-2011), Sashko (b. 1937—died after a year and a half), Mykola (1942-2000), Olha (1945-2013), Andriy (1949-2010), and me—Serhiy. I might not have come into this world. It was about two months before my birth: my mother went for water and, while drawing a bucket with a long pole, she leaned over and fell headfirst into the well (it must have been me who pulled her into the well). But she managed to turn over and splash into the water feet first. The well was lined with stone and not deep. Clinging to the stones, my mother got out of the well and came home, soaked to the waist.

In the same year, my father had to do some fighting. He was mobilized and took part in the war with the Poles. During one attack, he came under machine-gun fire. But he hit the ground in time, and it all ended without consequences. He was also an interpreter (he knew some Polish) during the interrogation of prisoners. And in early 1944 (when the Soviets arrived), he was mobilized again and thrown to the front. He didn't fight for long because in the trenches near Shepetivka he got frostbite on his toes; some of those sitting in the trenches with him froze to death. Father was sent to a hospital in Tambov, where his frostbitten toes were amputated. Kindrat and Vasyl were also at the front. (Kindrat was not only at the front. In the late 1940s, being hungry, he stole something edible and ended up in a camp in the Krasnoyarsk Krai. I remember: it was evening, Mother was sitting by the stove, in which a fire was blazing, and crying, remembering Kindrat). Already in the camps, I was amazed: how could they have participated in that war after such a famine? After all, if you take my father, when the front was approaching, he could have put his family on a cart (which I told him many times) and moved west. Moreover, both he and others knew well that the Soviets would mobilize them, and if they didn't die at the front, the collective farm and the NKVD would await them again.

Here I want to mention the family of my father's sister, Natalka. Her husband Kyrylo, like my father, was mobilized and died. Six children were left as half-orphans. And in 1948 or '49, they started rounding up young people in the village (just like under the Germans) and sending them to Donbas to mine coal. They tracked down Kyrylo's daughter—Zhenia—at night (she was hiding), caught her, and took her to a mine in Donbas. I was also amazed by the Germans: they knew that men fit for mobilization would be mobilized by the Soviets after their retreat and would fight against them. There was only one way out: either these men—the future reinforcements of the Soviet army—move west; or, if caught in the territory they were to abandon, they would be destroyed. And such a measure would undoubtedly have been advantageous both to the Germans and to those who did not want to be mobilized and die at the front for the interests of those who had driven them into collective farms, starved them, tried them for an ear of grain, and shot them.

Father maintained neutrality—“it's none of my business.” He was drawn neither to the Soviet partisans nor to serving the Germans. As for fighting both occupiers—for an independent Ukraine—he had heard about the UPA unit of Derkach raiding our area, but for him, as probably for everyone in the village, this was something distant. Father did not go to the partisans, but the partisans came to him. Someone informed the partisans that father had a new sheepskin coat. The partisans came to our house at night and demanded it. Of course, if the coat had been hanging in the house, they would have taken it, and that would have been the end of it. But father already knew that partisans were rummaging through houses at night, so he hid it well and said that he had no new sheepskin coat. Then they took father out behind the house to the ditch. A partisan clicked the bolt of his rifle and said: “The coat or death!” In addition to a couple of coats, they also took a heifer.

Father also had dealings with those who served the Germans. One day, he was summoned to the village elder, whose office was in the former village council building. As soon as my father arrived, the elder gave him a rifle and said, pointing to a man sitting on a bench:

—“We caught a partisan, guard him.”

And soon after, he came to my father again:

—“Take that broom and sweep the floor.”

Father puts the rifle in the corner, takes the broom, and sweeps. Seeing this, the partisan darts through the door, jumps out onto the street and, leaping into a horse-drawn cart, disappears. I heard about that partisan’s heroic escape more than once at the club during the celebration of another anniversary of the Soviet victory. The name of the man who swept the floor was not mentioned. Undoubtedly, although my father was not in the police, if that partisan had known my father and pointed him out, my father would have been not at the front, but somewhere in the North with the policemen. But what is strange is that this partisan’s hands were not even tied. And so the question arises: wasn’t it the elder himself who organized that partisan’s escape in this way?

And yet, my father did not entirely stick to “it's none of my business.” I don't know under what circumstances it was, but risking his life, he undertook to help one of two or several Jewish women who managed to escape being shot. Even as a child, I heard that a Jewish woman was hiding in our house. And when I gave an interview in 1989 for the bulletin “A Prisoner’s Page,” I told this episode, but with some mistakes. Later, while visiting my brother Vasyl, I asked about the events in the village during the war and, in particular, about that Jewish woman who was hiding with us. This is what he told me: “Sofiia Abramivna was my teacher. She hid in our house. In the summer, she would also sit it out in the khvos (ditch) overgrown with bushes. I would bring her food there. When they were burning houses, she was in the house. There was no certainty that they wouldn't burn ours. She needed to be led out of the house. So then, when you were watching the house burn (and that was when the Germans were burning the houses of those about whom they had some information regarding their connection with partisans), my father and mother, shielding Sofiia with their bodies, moved her to the barn. Sofiia stayed with us for a few more months, sometimes going out into the village. What happened to her—I don’t know. She left and didn't return. The police probably caught her and shot her.”

Sofiia Abramivna did not appear in the village. Thus, her life ended tragically somewhere, just as it ended for the Jews of the village of Rohachiv in the fall of 1941. That fall, the Germans gathered all the Jews (over 400 people. I. Liberda, “The Village Remembers”), took them to the Kamianobridsky forest, and shot them. Only a few people were saved. Incidentally, a third of the village’s inhabitants were killed, and the authorities never mentioned them. Their graves were treated the same as the graves of those killed by starvation in 1932-33. As if they had never existed.

In the village, the Jews lived compactly (in the mid-19th century, there were more Jews in the village than Ukrainians and Poles combined). And when three collective farms were established in Rohachiv in the 1930s, one of them was a Jewish collective farm called “Pyatyrichka” (Five-Year Plan). This collective farm also had a number of Ukrainians. I remember a villager’s story about those collective farms: “It was easier in the Jewish collective farm. If a woman didn't have time to bake bread before going to work, the head of the collective farm, coming into the house, would say to the woman: ‘Hurry up and finish and come to work.’ And he would leave the house. But in our collective farm: he came in, saw that a woman was kneading dough, and a fire was blazing in the oven, without saying anything, he grabs a bucket of water and throws it into the oven.”

In the first days of January 1944, the Soviet army was already in Rohachiv and took up defensive positions on the outskirts of the village, on the side of Novohrad-Volynskyi (that part of the village was called “Pletianka”). A certain military unit also arrived at our house. Upon arriving, they dismantled the northern wall of the large room, rolled a cannon in there, and from that cannon, they fired at the German troops, who were moving in a column along the highway from the direction of Novohrad-Volynskyi. Encountering the ambush, the German troops, having suffered losses in manpower and equipment, were forced to turn into the field and move along the snow-covered trackless terrain towards Smoldyriv.

For a long time, almost until the end of the 1940s, burned German trucks stood on the left shoulder of the highway outside the village. And the fallen German soldiers lay in the field and ditches until spring. When the snow was gone, they gathered teenagers, appointed one of the adults as a brigadier, and sent this brigade to collect the corpses. Brother Vasyl was in that brigade. As he later told me, they would drag the corpses with a horse to two former silage pits, which were in the field not far from the highway, right outside the village.

A comical incident also happened with their brigadier then: among the corpses was the carcass of a large draft horse. They dragged that horse over but couldn't push it into the pit. The brigadier came to help. Standing at the edge of the pit, he grabbed the tail and pulled. And then the tail, which had already started to rot, broke off, and the brigadier flew into the pit onto the corpses… (This happened at a time when the Soviets, after the German occupation, had not yet driven the peasants to complete impoverishment—to starvation. If that horse had died a little later, it would not have lain until spring. The peasants would have eaten it).

I remember myself before I was four years old. This must have been in the early autumn of '43. There was no snow yet. As I see it now: I am standing by a stool, on which there is a large frying pan filled with yellow cracklings, and in the other room, people are standing by the window, looking out. The people are anxious. This anxiety was transmitted to me. And I, leaving the pan of lard, go to that room and climb onto a bench. I look out the window and see: diagonally across the road to the left, a huge flame, and not far from that flame, someone is standing dressed all in black. I look at the flame. I also see my father, who is walking around the yard. My father is also somewhat anxious. It was only later that I learned that it was the burning house where the Antoniuk family (nicknamed “Kachurs” in the village) was living at the time.

I also remember how we were riding through the field in a blizzard on a sledge (hryndzholy). That winter, my parents, fearing that we too might be burned, fled from Rohachiv to the Kykivsky poselok. That was my first contemplation from what was left in my memory of the world around me and some vague reaction to it. My first comprehension of the world and myself in it—my reflections on life—formed somewhere at the end of March or the beginning of April of '45.

So, although so many years have passed, it's as if it's before my eyes: I am sitting near the threshold on the pryzba (a raised earthen bench along the outside of a rural house) warming myself in the sun, which is sometimes hiding, sometimes rolling out from behind small dark clouds; I am looking at the white snowdrifts with thawed patches and, in a very depressed state, I think: mother will die, and father will die, and I will die. And such a previously unknown sadness and hopelessness enveloped me that it is difficult to describe. I don’t know why I thought so much about it then. But I think the cause of this sadness was the death of Grandma Nastya (March 18, 1945). I remember her only as being ill. She was lying in bed, and I would bring her water, sweep the floor, always fussing around her to help with something. I remember the funeral too. The house was full of people. I was also holding a candle. But melted wax dripped on my hand, and I dropped it. Grandma loved me and always gave me a piece of something tasty that they got for her, being sick. Probably, that was when I first realized that death awaits a person.

My childhood, like that of almost all the children in the village, was spent in such poverty that it’s even surprising how I and everyone in the family survived those hungry years. When spring came, one of my activities was to go with my sister Nadia across the Sluch river and look for sorrel on the riverbank. And we didn’t always manage to gather enough of it, as many children were picking it. So we also went to the fields to pick what was called “rabbit” sorrel. A gang of kids would also raid the collective farm's vegetable garden. And one time Rud (he held some position in the collective farm) caught me in the pea patch and hit me on my soft spot a couple of times with the belt he held in his hand. He yelled at me, and it scared me a lot. That was in '46. Peas were a delicacy, especially when boiled. Sometimes, at dusk, Nadia and I would pick two bags, bring them home, and mother would immediately boil them in a large pot, and our whole family would feast. And yet, from '47 to '49, it was somewhat easier for us than for others. At that time, father was in charge of a small farm (in the 30s he had completed some veterinary courses), so I would go to the farm with my younger brother Mykola, and one of the milkmaids would treat us to some milk.

Yes, that was in the summer of '47. We had already drunk our milk and were walking home from the farm. Our stomachs were full, and it was a bit hard to walk. It was especially hard for Mykola because he was still very small, and besides, he had a big belly, while his arms and legs were thin. We rested in an orchard near the road—all that remained of the Matviychuk khutir—and then walked on. We often went to the farm to drink milk. And then father became a storekeeper. It seems we had enough bread then because I could take a piece of bread out of the house and give it to one of my friends. Sometime in '49, my father was removed from this position. I know that while in this position, he helped others as much as he could. And he bailed them out. One time, a woman who worked in the warehouse took some flax fiber (which means she stole it) and was taking it home. On the way, she was intercepted, and they found the fiber on her. But, luckily for her, one of the villagers witnessed this event and immediately informed my father. Knowing the woman's explanation, my father entered her surname into the list of those who took fiber home and forged her signature. Soon, those who had intercepted her appeared. Father confirmed what the woman had said and showed them the logbook. This saved that woman from a possible prison sentence.

What also helped us was that my mother had a weaving loom, and she often worked even at night, by the light of a kahanets (a simple oil lamp), weaving linen and coarse cloth to order. I helped her in this as best I could—by winding spools. Others wound them too, but I had to do this work the most because I knew that my spools were better than those wound by others. Mother always praised me.

And one time, people from the village council came and said: pay the tax. But there was nothing to pay with. So they took a roll of linen from the loom, which my mother had just woven, and left the house with it. If anyone got it hard, it was my mother.

It’s chilling to remember sometimes. The collective farm quotas, the vegetable garden, the house that had to be kept in decent condition, the household chores, the children; processing hemp into fiber, spinning thread from this fiber and wool on a spinning wheel, weaving and sewing clothes—from pants to a svytka (a traditional outer garment). It's terrifying! It’s easier in prison. Besides—it was voluntary, not like in prison. One could have run away somewhere—even to prison. How was it possible to endure such a thing?! I don't know. But what's also strange is that in such poverty, young people came together, even had some sorts of weddings. People lived in such destitution, had so many troubles, yet they "produced" new people, creating additional trouble for themselves. (Later, in the camp, recalling that period and analyzing the life of the poor in general, I came to the conclusion: the poor who have children do not deserve sympathy. Is it worth sympathizing with the poor who have nothing to feed their children with?! And their children?! After all, when they grow up, they will repeat what their parents did. It is better to pity a hungry dog. So if you see a hungry woman with a child and a bitch with a puppy, throw a piece of bread to the dog—its “head is smaller.”)

Sometimes my parents would reminisce about their childhood, their youth. In their memories, there were roasted piglets and all sorts of delicacies. And their own horses. To me, it was something unreal. They also recalled bits and pieces of '33. My father often remembered how he was walking from Rohachiv to Novohrad-Volynskyi, and there were corpses lying on the roadside. Those were the people who were trying to get to the city to save themselves but didn't have the strength. Some of those lying there still showed signs of life. One of them raised his head and asked: “Give me a glass of milk—and I’ll go on.” He didn't even ask for bread, because he knew no one had any. But where could my father get that glass of milk...

In 1947, I started school. My sister Nadia brought me to the classroom (a small room in the village council), sat me down at a desk. Then came recess. I grab my notebook and—head home. I thought classes were over. I didn't have a primer. And not just me, many didn't. So I started reading somewhere around New Year's when they got me an old primer. I studied haphazardly. But I was fascinated by fairy tales, eagerly immersing myself in that world someone had invented. The first fairy tale I read, which was the best of all fairy tales for me, was called “Kotyhoroshko.” I read with pleasure and retold tales to the little ones. This wasn't difficult for me because in the first years after reading a tale, I could retell it word for word. (Still, I must say that all those fairy tales and myths are harmful because from childhood they implant in a person’s subconscious the possible existence of all sorts of devilry). And later, I read works that my sister brought for herself. Neither my parents nor the teachers paid much attention to me—he’s studying, so let him study. So even though my father discovered before I started school that I had poor eyesight (hereditary myopia—from my mother), it somehow happened that no one wondered if I could see anything on the blackboard. The teachers probably didn't even suspect. I kept quiet and didn't even know at first that I needed to use glasses, as in the first years of school, no one in the class wore them. It's possible that they were not so easy to buy in those years. Because of this, I constantly had to look into my neighbor’s notebook because I couldn't see what was written on the board (especially in mathematics).

This, I think, to some extent affected my success in acquiring knowledge, my desire to learn. And in general, I don’t remember ever having a penchant for acquiring the knowledge that school could provide. I remember those children who studied in the 40s: hungry (some would even take pieces of bread from others), ragged, barefoot. A particular incident also stands out vividly in my memory. The winter of '49 or '50. During recess, someone said that a dead man was lying on the road not far from the school. We run out of the classroom and go to look at him. It was not far, so we immediately saw a black spot on the snow near the grave of the fallen soldiers in the center of the village. We run up and examine with curiosity and some fear an unknown man who is lying almost face down, with his legs slightly bent, half-covered with snow. We look and run back, leaving a dead person, needed by no one, on the highway in the snow.

And another scene from those years: spring, the snow has already melted from the gardens, melted from the collective farm field not far from our house by the ditch (potatoes grew on it last year), and the field is full of people. Mostly children and teenagers. All with spades—we are looking for last year’s potatoes in the ground. The potatoes are already rotten, but you can still bake something resembling deruny (potato pancakes) from them.

Still, despite this extremely impoverished life, I did not hear anyone at school complain about this destitution, or blame the authorities for what was happening around us. On the contrary, we read with fascination works that glorified the Cheka, the Red Army, and their struggle against the kulaks for the establishment of the collective farm system. So I, like everyone else, avidly read the works of Soviet hacks in which only the Bolshevik-communists fought for justice, were those to be emulated. Gradually, thanks to the school, the works I read, and the films, which were a rarity for us at that time (but it was great luck to get into the auditorium; we also watched through the window), we were becoming Soviet patriots and were ready to repeat the feats of those child partisans about whom we read in books and saw in films. This is how the zombification of children took place, and parents were afraid to open their mouths, for how could they know that their child would not tell someone about it at school. I remember that by about the fourth grade, I was proving to my parents the advantages of collective farming over the private farming they so often reminisced about. But that was in theory, because when I broke away from the tools of zombification, I fell into a kind of duality caused by what was real—our impoverished life.

Perhaps my parents were also afraid, because they did not openly blame the authorities, only in a veiled form. And since in those years the chant "Long live Comrade Stalin!" was constantly heard, my father, after looking through a newspaper, would very often repeat: "May he live long, graze, and lay eggs on the nest!"

But despite my pro-Soviet attitude, I, unlike others, for some reason did not recognize communist paraphernalia. I could not put on a Pioneer pin and necktie. To me, it was something unnatural, superfluous. Only once, when the whole class was being photographed, they brought a necktie, and the teacher with the students, surrounding me, almost by force put it on my neck. Thus, I was photographed in a necktie. It is still unclear to me why I resisted so much then. Perhaps from a young age, I had an aversion to any kind of insignia and symbols that had to be worn on one's person.

Incidentally, I want to say that no one did as much harm as the schools, writers, and cinema. They instilled a negative attitude towards private farming, towards those who fought for it. They also instilled a love for the Chekists, the Soviet army, a love for the capital, Moscow. And no matter what talent those Honchars, Dovzhenkos, and those Korolyovs had (it would have been better if that Korolyov had not returned from Kolyma), of whom the so-called Sovieticuses and the feeble-minded are so proud, this talent gives no grounds to absolve them of guilt. (After what the Bolshevik-occupiers did, there could be no creative cooperation with them. Therefore, one should not grieve too much for that “Executed Renaissance”). And the greater the talent, the greater the harm done. It would have been better if they had no talent. It would have been better if they had worked on a collective farm instead of carrying a “fig” in their pocket while simultaneously praising in their works everything that should have been cursed. And perhaps it would have been better if children had not gone to school at all. Although that, of course, would be a paradox. And yet, if Ukrainians, like the Roma, had attended school less, then, perhaps, they would have been much better preserved as a nation. (As Prime Minister Nehru of India truthfully said: “An intelligentsia raised by an occupying power is an enemy of its own people.”)

In April 1951, our whole family left on a recruitment program for the Odesa region. Besides us, several other families left the village. My father's brother, Oleksandr, and his family also left. Everyone was looking for a better life. Perhaps my parents would not have left if the collective farm had given them at least what they had earned for the trudodni (workday units) they had from the previous year. But they didn’t. And here was this rosy picture of the life that awaited them—according to the recruiter. In addition, the authorities provided those who relocated with significant (by those standards) material assistance.

At the end of April, we were taken by truck to the Dubrivka station. About a day later, we loaded into wagons. It was a train of about ten wagons, filled with recruited people. We were riding in a boxcar. The wagons had two-tiered bunks on the sides of the doors, with a potbelly stove in the middle and a small hole in the floor—the toilet. At the top were two small windows. Probably, those wagons were used to transport prisoners to the north, and here they were used to transport settlers. We traveled for several days. We had long stops at large stations. At such times, we stocked up on water and fuel for the stove. Mostly it was coal, which was stolen from wagons standing at the station. And at one of the stations—either Koziatyn or Zhmerynka—we went through a sanitation checkpoint and took a shower. There were about five families in the wagon, so it was noisy, I would say, even cheerful, although everyone had some sadness in their soul, because they had left behind their native places, relatives, and friends, whom they didn’t know when they would see again. Nadia and I mostly sat on the upper bunks by the window, watched the passing landscapes, and often sang mournful songs: we felt sorry for what was left behind, somewhere far away. (By the way, I should also mention that although we all had some talent for singing, Nadia and Andriy stood out with their voices. Especially Nadia, who captivated listeners with her performance of lyrical songs. She was one of those who, with a favorable fate, could have become famous singers).

Finally, the last station—Buyalyk. Families are being distributed among the villages. Or rather, among the collective farms. A truck comes for us too. After loading our belongings, we go to the village of Pavlynka, Ivanivka Raion. Upon arrival, we settled in a solid house with a galvanized tin roof, occupying one of two large rooms; the kitchen was shared. That house had been one of the school buildings before the new school was built. Soon, my parents received additional assistance for the settlers. So there were no more problems with bread. My parents immediately went to work on the collective farm, and I, along with Nadia and Mykola, went to school. Besides us and my father's brother Oleksandr's family and a family from the village of Ostrozhok, several other families lived in Pavlynka—settlers from Western Ukraine, who had arrived in the village a few years earlier. The elders among those settlers differed in their dialect not only from the local people but also from us. In fact, we who had come from the Zhytomyr region had no noticeable language differences with the locals, and so we felt that the local population perceived us as their own. We were to settle in this village for good. They immediately allocated us garden plots on the outskirts of the village, and we began to build houses from the edge of these gardens. The construction went quite successfully because by August the houses were walled up. All that remained was everything related to carpentry. Those houses, of course, were not given for free; the costs had to be repaid.

We—the children—gradually grew into that steppe village, which was foreign to us. And when summer came, we immediately felt the limitations in summer entertainment, because while in Rohachiv at that time we would run to the river, the pond, or even splash in the ditch when there was enough water after the rain, here there was nowhere to swim. Moreover, the summer was hotter, cloudless. There was no pond yet, and although we could have swum in the village pond not far from the Koshkove halt, we kids for some reason made our way to the Kuyalnyk Estuary, which was about seven kilometers away. So, a gang of us local boys would walk along the steppe road to the estuary, swim in the very salty water, and walk back. There was nothing pleasant about those trips. I remember how my brother Mykola also wanted to join our gang. I tried to talk him out of it, explaining that it would be too much for a little boy like him, but he still ran after us. Then, to get away from him, we would run at such a speed that he could no longer keep up with us. Seeing that we were already far from him, Mykola would stop. I felt sorry for my brother, as he also wanted to splash in the water, but how could we take him with us?

p>

That summer, I almost died. This was already in August. We were playing soccer. We were sweating. I get a bucket of water from the well and pour it over myself. Soon, I felt some kind of malaise, which completely knocked me off my feet. I lay in the room for days. I had periodic hallucinations: a ball, some other object would grow from its normal size into a huge one, then shrink until it disappeared. From time to time, I would lose consciousness. Finally, they take me to the hospital in the village of Severynivka. My temperature was over 40°C. I was in the hospital for over a week, and when my mother came to visit me for the umpteenth time, she was allowed to take me from the hospital. I still felt weak, but I wanted to go home, and I was very glad that they were letting me out of this strange building. Shortly before sunset, we were already in Pavlynka.

In September, we were moved to an old house with several rooms. In one of the rooms lived the owners of this house—a very old grandfather and grandmother, whose son was soon to take them to live with him in Odesa. And they left soon after, leaving us that house, which had already served its time. The house was not far from the club. And behind the garden was the school. The location was not bad. Besides, there was an orchard. I also made friends here—Koliunka and Marko. Mykola's house, whom everyone for some reason called “Koliunka,” was nearby. We would visit each other. And Nadia was friends with Marko’s sister. Their mothers (their fathers had died) also used to visit us. While visiting us, among other things, they would talk about how they had lived earlier, in the post-war years. I remember that Marko's mother, to feed her children somehow, moved from the city to the village, and Koliunka's mother, working near the grain (probably on a threshing floor—grain heaps in the steppe), would pour grain into her boots and thus bring it home.

For some reason, my parents did not plan to wait until a new house was built for them, although it was clear that in a year or a year and a half, the house would be ready for occupancy. As early as the spring of 1952, having found a house in the village of Severynivka, my father went to Rohachiv and sold our house. Upon returning, he bought one in Severynivka. Why he did this is hard to explain. After all, no one was kicking us out; we had a place to live. And the house in Rohachiv was not empty. And besides, Severynivka at that time was a less convenient place to live because there were no buses then, and the only way to get to Odesa, 40 kilometers away, was by catching a ride, and only when the road was good (it was still a dirt road). Or via Pavlynka to the Koshkove halt, where a suburban train stopped. And that was over 12 km away. From Pavlynka, it was half that distance. In winter, settlers from Rohachiv who lived on a khutir in Severynivka would sometimes spend the night with us. Arriving late in the evening in Pavlynka from the halt, someone from that family would stay with us overnight, and at dawn would set out for Severynivka, pulling a sledge or carrying a bundle of purchases on their shoulders. Perhaps the desire to socialize with this family and two others, one of which lived in Severynivka and the other in Oleksandrivka, not far from Severynivka, was the reason for the move.

We left Pavlynka when the apricot trees were already in bloom. The dwelling that my father bought was half of a large house with a tin roof; the other half was occupied by the family of a collective farm brigadier. Adjacent to these halves were also sizable garden plots, divided in half by a low stone wall. At the end of these plots grew half a dozen huge old pear trees and young trees. All this was enclosed by a meter-high wall of stone, of shell rock that is quarried in the Odesa region. And behind this house stood another one, from which it was about 250 meters to the village. The Yukhymenkos lived in that house, and our family was friends with them. So we were like on a khutir of two houses—between Severynivka, which stretched along the hollow along the western bank, and a khutir of several dozen houses that stretched under the high eastern bank of what was once, probably, a large river that flowed into the Black Sea, and later became the Kuyalnyk Estuary, which was a few kilometers from the village. And to the north of us, beyond the small bridge over the Kuyalnyk rivulet, which, bypassing the Yukhymenkos' house and gardens, flowed into the estuary (it dried up in the summer), stretched a still young forest into the distance.

And again, my parents went to work on the collective farm, and we, the older children, went to school. For us children, there were significant advantages in Severynivka. Here, all summer long, we swam by the little bridge in a small reservoir and in a much larger one in the forest. We also went to the forest often, played various games, mostly, of course, "war." We also went to help our mother weed her quotas. And in winter, there were places to ice skate. Compared to Pavlynka, it was simpler here, perhaps because we were living as if on a khutir.

It was then, amidst the fun and minor mischief, that I committed an act that I later regretted. This is what happened... Half of the house my father had bought belonged to a family that had been deported from the Carpathians a few years earlier. I think it was a forced resettlement. That gazda (master of the house), with the surname Savytsky, having settled in that house, had put up, as was probably customary in his area, a figura—a large cross (over three meters high) with an icon of the crucified Jesus on it. The cross stood not far from the house in the garden that bordered the road. I had never seen such a large cross standing next to a house. To me, it was like something alien, obsolete, something that had no place near a house. It was truly like a challenge to everything that declared religion the opiate of the masses. And the strange thing was that the cross stood there, and the authorities took no measures to remove it. I didn't like it, and I told my father that it should be taken down, but my father said: "We didn't put it up, and we won't take it down. Let it stand." I often played with my friends by the cross in a game popular among the village children at the time: a column of about five small stones was set up, one on top of the other. Holding the end of a flat stone with your fingers, you threw it from a certain distance to knock down this column. The winner was the one who achieved this result. (We loved this game, so we didn't even go to school, where they were broadcasting Stalin's funeral on the radio). I don't remember what pushed me to it, but one day I took a small stone and threw it at the crucifix. The glass from the icon shattered on the ground. This was sometime in the summer of '53. Years later, remembering this incident in my cell, I thought: why did I do that? After all, you cannot hate someone who is against hatred, you cannot throw a stone at something for which Jesus is a symbol, you cannot throw a stone at Jesus. No, I was not a Christian, but I understood that it was unjust on my part.

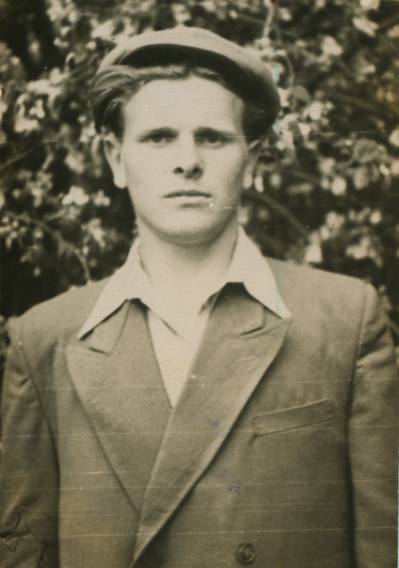

As for that gazda, before selling his half, he built a new house on that khutir, later explaining to my father that it was closer to the collective farm fields for him. And indeed: he went up the hill, and he was already in the field. Not like for us, who had to walk about a kilometer across open terrain. His son Mykhailo also often visited us; there is even a photo preserved: he is in the middle, with Nadia and Valya Yukhymenko on either side. Later, this family left, probably returning to their homeland in the Ivano-Frankivsk region.

In the Odesa region, life was somewhat easier, especially for my mother, because here they didn't grow flax, potatoes, and some other crops. This was a steppe region, where the main crops were wheat, corn, and sunflowers. In addition, the fields were mostly cultivated with machinery. And in winter (except for work on the farms), there was nothing to do. So the quotas were much smaller. It wasn't like in Polissia, where in winter, in unheated "points" (processing sheds), flax was manually processed into fiber. (I went to such a "point" for shives. I saw women working even in the severe cold in that dust—there was no ventilation). Mother no longer wove. Although even in Polissia this craft was going out of use; civilization was asserting its rights.

But poverty remained, as it had been. We could have lived better, but for that, we would have had to steal at least from the collective farm field, and my father couldn't bring himself to do that; he just couldn't adapt to life on the collective farm. (Like his brother Oleksandr, an overly delicate soul: when a chicken needed to be slaughtered, his wife Khrystia would do it). Even the guard at the threshing floor, noticing that my father never took anything for himself in his cart (he sometimes worked as a driver), was dissatisfied with my father and once told him: "We're afraid of you. You don't take anything." Later, reminding my father of what the guard had said, I even reproached him for not being more active in obtaining at least edible supplies. And living in Pavlynka with his brother Oleksandr, they soon moved to different villages, instead of staying together, helping each other provide for their families from the collective farm field, or even from the farm, where there was plenty of meat. So when the flour, milled from the grain given for the trudodni, ran out, we had to carry milk on our shoulders and something else that could be sold at the market in Odesa, and having walked to the Koshkove halt, take the suburban train and, after selling our goods in Odesa and buying bread, sugar, and a few other things, make our way back home.

We stayed in Severynivka until April 1954. It was decided—we were returning to Rohachiv, as we received news from our correspondence that life in Rohachiv had somewhat improved, not like it was before our departure from the village. Besides, my father started to get sick often, and the doctors said he needed to change the climate. My father missed Rohachiv, probably also because, among other things, he had two other sons there from his first wife. As for my mother, she didn't want to go back, as she knew what awaited her there, what she had left behind. But still, she didn't defend her opinion very strongly. As for us children, what did it matter to us: if we're going, we're going. It was even interesting—we would travel again. And we would meet our old friends, with whom we occasionally corresponded. So in April, without any reconnaissance, my parents sold the house and we started preparing to move. Finally, everything we could take was packed in sacks, and we left for the Buyalyk station in a hired truck.

We were leaving with a smaller family. In the fall, Nadia had married Pavlo Nazarenko from Oleksandrivka and moved to live with him in Odesa. We are leaving, but with sadness in our hearts, because we are leaving Nadia for good, and everything here has become dear to us. With sadness, we part from those we were friends with, with whom we played various games. Especially with our neighbors, the Yukhymenkos, with whom we socialized the most: Olha and Pavlo. But it’s all over now, we have to go.

The neighbors who came to say goodbye to us were left behind, and our little dog, Dzhulbars, about a year old, ran after the truck for several kilometers, sometimes falling behind, then catching up again. It fell behind for good when we were leaving Oleksandrivka, climbing out of the hollow towards Buyalyk. After unloading at the station, we wait for the train to Odesa. And here my father, for some reason looking into one of the sacks, discovered my saber, which I had secretly hidden when we were packing. Although this saber was very rusty, I didn't want to part with it. But what could I do?! I didn't throw it away, but right there at the station, I tucked it under a piece of turf, hoping that I would come back later and retrieve it. What comforted me a little was that at the bottom of a sack lay a German bayonet, and I would get it to Rohachiv.

At the train station in Odesa, Nadia came up to us with her husband. Crying, she says goodbye to us. We return in comfort. We have a separate compartment, even with mirrors in it. Everything is clean, comfortable, not like it was in that boxcar. Upon arrival in Rohachiv, we lived with my father's sister Natalka for several weeks. My father was looking for a house, but there were none for sale in the village. He found one in Tartak, moved it, and started building in the poselok, not far from the technical school, which had appeared before the war as a result of the liquidation of the khutirs. We moved from our aunt's place, who also lived in the poselok, into a shack and lived in it all summer until they built that tiny, two-room hut. My father already regretted coming back, but there was nowhere else to go; he had to settle in somehow. And how much simpler everything would have been if the house had not been sold, and upon our return, we could have settled into our own home. But as it was—we had to build, we had to go to work on the collective farm, and we needed something to eat.

I stopped going to school; I spent the whole fall helping my father look after calves. And for the next two years, in the warm season, I worked at the technical school at various jobs and on the construction of collective farm pigsties. Of course, the wages were paltry, and I couldn't provide financial help to the family. What I earned wasn't even enough for me to live on. What helped us to a great extent was that the collective farm fields were nearby, and my father and I would drag things from there. Mostly potatoes and beets. And more so in winter from the clamps, because it was much easier on a sledge. We did this quite often. But as for getting grain or some livestock for meat, that was "taboo" for my father. I once hid about ten sacks of rye and wheat in the corn near the house. When it got dark, my brother Mykola and I carried that grain all night. When we were on our last trip, it was already getting light. And my father just grumbled disapprovingly, frightening us with prison. But after some time passed, he didn't hide his satisfaction that he was provided with grain.

In those years, the best for me was 1957. Having bought a new bicycle in the spring, I and my friends, most often with Anatoliy Kovalchuk, would race around the village, to the river, to the forest to the swing behind the village of Rudnia, where young people constantly gathered. I also traveled with one of my friends to neighboring villages—just to meet some girl who was more to my liking. Those girls were like toys for a child—the more, the better. Nothing serious ever came of it. I never told any of them that I liked her. And I never brought flowers to any of them. All those acquaintances were just fun, a pleasant way to spend time. It couldn't have been otherwise, because from childhood my role model was “Сагайдачний, що проміняв жінку на тютюн та люльку.” (And yet I must say that in my childhood, I fell in love three times with blond-haired girls. The last of them—that proud girl (it is of such that they say: “...Ой, ти, дівчинонько гордая!”), I confessed to when she was already in her 72nd year. And it's a good thing it was so late because it could have ended as it usually does. But is it worth writing about such things?! After all, it's physiology. When you see a couple frozen in an embrace (there was no such thing in the years of my youth), you immediately associate them with a similar couple of frogs frozen in a swamp. Of course, this would be another story about being in love. But there would be nothing new in it, because for as many people as there have been and are—that’s how many stories of love there are. And they are all cut from the same cloth. The nuances are not worth attention. I will only say that if people walked around naked, there would be less poetry—and delusion).

And I was working on construction (they were adding the second half) of the Rohachiv secondary school. By the way, on the site of this school, there used to be a cemetery and the Church of the Nativity of the Theotokos stood, which already existed in 1796, but when it was built remains unknown. It is only known that the day of its consecration is September 21, which the village still celebrates annually as a "feast day." When the communists dismantled the church, either in 1929 or already in the 30s, the old cemetery also ceased to exist.

The workday was 8 hours, so there was enough time for fun. Yes, that was the best year, and there was never another one like it. It was as if I had a premonition that there would not be another one, because I remember, already in the fall, returning from Ostrozhok in the evening and sitting down on the aftermath hay, I said to my friend, with whom I had worked and hung out everywhere that summer, Anatoliy Kovalchuk: "There will never be another summer like this."

Already in January 1958, I joined a construction brigade of carpenters and worked in this brigade until the frosts set in: we made roofs, doors, and windows for cowsheds and a “point.” We worked on contract, so we worked from sunrise to sunset. There was not much time left for fun. But under the guidance of my distant relative, Andriy Kostrytsia, who was a remarkable joiner and carpenter, I quickly mastered the carpentry and joinery professions and began to make doors, windows, and other things on my own. That autumn, I was supposed to go to the army with my peers. But I didn't. They went, and I was given a gray ticket (rejected due to myopia). Although I really wanted to join the army—I was drawn to weapons. And it was somehow awkward in front of others: they went, and you were rejected. And it was not the first time I was rejected. It had happened before. In the fall of '57, my friends Mykola Tymoshchuk and Andriy Dilodub and I decided to go to Donbas to an FZO (Factory and Plant Apprenticeship School). We were brought to the assembly point in Zhytomyr. We go through the medical commission. Knowing that I might be rejected due to myopia, I sent one of the guys to the eye doctor. It worked, and it seemed that everything was behind me. I go to the last doctor, the "ENT." The doctor looks up my nose and says: a polyp in the nose. You won't go to the FZO, because you need surgery first, and only then will you be able to go. My pleas (neither my friends nor I wanted to part) did no good. I had to return home.

By late autumn, the brigade had completed everything that was in the contract. And I had no desire to work on the collective farm anymore; I didn't want to be a collective farmer, which I had automatically become (like the sons of serfs once were), without applying to join the collective farm. I started thinking about how to get out of the village and find a job somewhere in the city. I went to the village council to get my registration removed. I already had a passport because when I wasn't allowed to go to the FZO, my friends, whom I had seen off to the station, begged the escort to give me my passport at the station. That passport was without registration, and therefore invalid. There was nothing left to do but to register in Rohachiv. So now the issue was deregistration. And so it began. I go to the village council, and the head of the village council sends me to the collective farm because "kolhospnyk" (collective farmer) is written in my passport. "Let the head of the collective farm give a 'spravka' (certificate), then I will deregister you," says the head of the village council. But he doesn't give it. And I started traveling to Baranivka, to Zhytomyr: to the raion committee, the raion executive committee, the oblast committee. And all in vain. Then—it was already somewhere in April 1959—I wrote a letter to the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Podgorny. I wrote that I had a fiancée in the Odesa region, that I needed to move to live with her permanently, that we couldn't get married because they wouldn't deregister me from the village. I didn't really have much hope. But in the second half of May, accidentally meeting me in the center of the village, the head of the village council comes up to me and says:

—“Bring your passport. I will deregister you.”

—“What about the spravka?” I ask.

—“It's not needed anymore,” answers the head.

Apparently, there, at the “First” Secretary’s office, they thought: what difference does it make to us in which collective farm he will work? Let them pair up and produce collective farmers for us.

Thus, only through deceit did I manage to deregister and have the opportunity to move freely around the country.

Taking a certificate from my place of work (I had been working for about two months on the highway section Rohachiv - Dovbysh, making concrete rings for bridges), I went to Zhytomyr in the first days of June and after a two-day search (I slept at the train station), I got a job as a carpenter in the NGCh ("chief of the civil section"—one of the departments of the railway administration, which repaired buildings and structures belonging to the railway).

Arriving at the NGCh on June 9 (a small building, which besides the NGCh office had several rooms for a dormitory), I settled in the dormitory. The windows in the room overlooked the station tracks. There were two of us in the room, although there was a third bed. But in fact, I had the room to myself because my roommate, Vasyl Holovnia, lived near Martynivka and, as a rule, would leave for home on a suburban train after work. This suited me; only I couldn't get used to the roar of the trains outside the window for a long time.

Everything would have been more or less normal if it weren't for the meager wages, which soon were not even enough for normal food.

As it got colder, the volume of work decreased, and accordingly, the already small wages also decreased. It was a good thing I had clothes and shoes, so I could get by somehow. But something had to be done to improve my financial situation. So I started looking for another job and in January 1960, I got a job at a furniture factory as a carpenter repairing the factory workshops. But leaving the NGCh, I had to leave the dormitory too. After staying for about two weeks in the apartment of one of the factory workers, I finally found an apartment to live in with registration. It was a private house on the corner of Skhidna and Kotovsky streets, opposite the school where I had been studying in the 8th grade of night school since September. (I went to school because I realized that to get a better place under the sun, you have to use your elbows, and you can't get such a place without some kind of diploma). And yet, changing my place of work did not solve the problems that were plaguing me. To some extent, those problems could have been solved the way some guys did, by marrying one of the Zhytomyr girls. But that didn't suit me. Besides, it was by no means in my plans to start my own family. My family for me was my parents, brothers, and sisters.

In the room I moved into, my roommate became Volodymyr Tarasyuk. We occupied a separate room in the old hosts' house. It was thanks to Volodymyr that I settled in this place. Working with me in the same brigade and learning that I had problems with housing, Volodymyr offered me to move into the room he was already renting. He was also from a village—Saly in the Cherniakhiv Raion. He had also been to an FZO. As it turned out, the same one as my friends who had gone without me in the fall of '57. Like me, he also had to think about how to make ends meet. We were poor, because even at the furniture factory, the wages were meager, and not only for us. Such wages were common for most of those who had secondary or auxiliary jobs. I remember a conversation between two foremen, which they had in the office in my presence: "We have to do something," one says to the other. "The girls didn't go to the canteen for lunch; they're standing by the fire, eating only bread and drinking water." These girls were also from the village. They worked in the cold, in a blizzard, as laborers on the construction of a large new workshop. They lived somewhere in rented rooms, were in poverty, but were glad that they had managed to escape the collective farm. And it was like that everywhere in the city. I was already thinking: maybe I should leave Zhytomyr and go in search of better wages? But I didn't want to leave school either, and where would I find a better wage in winter? And returning to the village was out of the question—who returns to the village from the city?!

There was only one thing left to do—rob a store. And I started walking around the city, looking for a store that would be easier to rob. I didn't share my thoughts with Volodymyr, because I saw that it was unlikely he would go for such a thing. My head was not only filled with plans of robbery. I began to think more and more about life itself, about its worthlessness. Well, what kind of life is it when you are forced to show up at a factory or in some office at a certain hour day after day, if you have the appropriate education. And so on until retirement, until old age. You are like a dog on a leash. Is that life?! It's not life, it's just work. That didn't suit me. After all, time spent working is time of a lost life. If only it were like in the old days! If there were a Zaporozhian Sich—I would have gone there, I thought, sitting at my desk. Although what kind of Zaporozhian Sich would it have been for me with my myopia—in the first battle, I would have been hacked down or shot.

It was somewhere in early April. I had no firearm, but in the village, there was the bayonet I had brought from the Odesa region. I didn't go to get it myself but asked my brother Mykola, who had recently arrived in Zhytomyr on assignment from the collective farm to study to be a tractor driver, to bring it. He fulfilled my request. Of course, I was only going to use that bayonet for intimidation, as I had no intention of stabbing anyone with it. And so I marked two stores, each with only one saleswoman. One was not far from the railway station, and the other at the Zhytniy Market. The one at the Zhytniy Market seemed more suitable for an attack. After observing the store for one evening, I came the next evening with the bayonet. Standing by the empty market stalls, I watch the store and the surroundings. It's already completely dark. The store is lit. There are no people anywhere. But for some reason, I hesitate. And then a man approaches me. He said he was a guard at the market and asks me:

—“What are you doing standing here?”

—“I arranged to meet someone here, but he’s not here for some reason,” I answer him.

—“Everything is closing, and outsiders are not allowed here.”

—“He probably won’t come now,” I say to him and leave the market territory.

I think that even if I had not been involved in political affairs, sooner or later, I would not have been able to avoid “criminal” cases, and thus prison. Why criminal—in quotes? Because I do not consider that during the rule of an occupier in your country, an attack on an official, a store, a factory or collective farm cash office, etc.—is a criminal matter. Regardless of whether this expropriation is for the needs of political activity or for personal needs.

But something happened that, it would seem, could not have happened in Zhytomyr, especially at the school where I studied. On the evening of March 4, 1960, leaflets were distributed near the school. During the break, students brought them into the classroom. I took one for myself. It was a leaflet from a Russian émigré organization, the NTS (People's Labor ). Soon, a KGB representative appeared in the classroom and addressed those present with a demand to hand over the leaflets to him. They began to approach him and hand them over. I did not. That same evening, my roommate Volodymyr Tarasyuk read this leaflet. And the next day, the owner of the house also read it. I also gave that leaflet to Borys Zhovtetsky to read, who was in the same class as me. (Zhovtetsky was a Pole; his grandfather was dekulakized, and in the late 30s, he was shot). And a few days later, while at the NGCh, I also gave it to Petrenko to read, with whom I had worked together.

After reading the leaflet, the owner of the house began to come into our room and tell us about the events in Zhytomyr in those turbulent years of '17-'20. He told us about the typhus in Petliura's army, and what life was like in Zhytomyr in those years. He also expressed his dissatisfaction with the existing order. Sometimes I would come from school, and he would be telling Volodymyr about the past. And once he got so carried away that he was telling us stories until morning.

About a week had passed since I brought the leaflet. One evening, I come from school, and Volodymyr is sitting at the table, writing something. I ask him:

—“What are you writing there so late?”

—“A leaflet,” Volodymyr answers.

—“Well, and what have you written there?”

Volodymyr reads what he has written. It turns out, the Jews were to blame for everything. About the communists—not a word.

—“What do the Jews have to do with it?! If anyone is to be blamed, it's the communists,” I tell him. “And if you really want to release a leaflet, then let me help you. We can partially use the leaflet I brought.”

Volodymyr agrees, and we immediately set about writing the leaflet. We didn't spend much time deliberating over it, and that same evening, or perhaps already at night, the text of the leaflet was ready.

—“Well, then, let’s give the KGB a run for their money,” I say to Volodymyr, because I too had become captivated by the idea of distributing our own leaflets around Zhytomyr.

So Volodymyr buys paper, and in the evenings, altering his handwriting, he writes leaflets in gloves. After some time, several dozen leaflets are ready. We decide that's enough for now. And so on the evening of March 19, I take about a dozen leaflets, take a tram to the railway station, post a leaflet somewhere there, and walking along Kyivska Street towards Skhidna, I paste leaflets on poles. I pasted the last one on a pole after turning onto Skhidna. I return to the apartment, where Volodymyr was already waiting for my return. We take all the leaflets, glue, and tacks, and trying not to draw attention to ourselves, we walk the streets in the city center until one in the morning, putting them up. Everything went smoothly. Although at the end of the leaflet was the slogan "Down with the communist system of oppression and terror," we carried out this work as a sort of routine affair—like a game, as we were not aiming for anything big, for achieving any changes in the country, let alone a revolution. It was all simple: Volodymyr was dissatisfied with the foreman who hadn't calculated his salary as promised, and I was just doing it for the thrill. Of course, I didn't think then that they might track us down, and then they would be the ones running, and I would have to sit for a long time. Although for us this action was a routine affair, after distributing the leaflets, we decided that in a week or two, we would distribute a new batch. Let them run.

Everything went on as usual. No changes. Only Volodymyr moved to work as a loader in a store, so we no longer worked together. And so we communicated little. I don't know if we would have distributed the second batch, because I felt that Volodymyr's enthusiasm, which he had especially on that evening when he was composing the leaflet against the Jews, had already faded. And no wonder, because not only I, but he too had personal troubles related to our destitute life. We had to think about how to improve our financial situation.

April was passing. Spring was in the air. On one of these warm, sunny days, when there were already large thawed patches, I was chopping wood in the yard. Then the owner of the house approaches me and says:

—“I’ll have to have you deregistered.” (I don’t remember anymore: was it because they were going to sell, or remodel something in the house).

There was a certain awkwardness in his voice, as if it was difficult for him to tell me this. And at the same time, a certain hostility. I feel that he is not in his element. It was somewhat strange to hear this from him, because until now, there had never been any unfriendliness in his voice. Well, now I have the hassle of looking for a new place to live again.

—“Alright, then I’ll look for a place for myself,” I say to the owner.

Around the same days, visiting the NGCh after work, I met with the head of the NGCh, Dubinin.

—“What happened with you?” asks Dubinin. “The police are interested in you.”

—“Nothing happened,” I answer.

Well, the police aren't the KGB. Who knows what they might be interested in me for, I thought. Besides, I was sure that the KGB wouldn't find us, because we hadn't told anyone about it and hadn't left any traces. I also met Nadiyka Kotenko (the sixteen-year-old daughter of the NGCh foreman) in the yard of the NGCh. When she saw me, she ran up to me. Her whole appearance spoke of how glad she was to see me. (About two weeks before this, I had accidentally met her in the evening near the "Ukraina" cinema, and her friend said to me in her presence: "Nadia has fallen in love with you." I had then promised that we would go to the cinema sometime).

—“When should we go to the cinema?” I ask Nadiyka.

—“Whenever you want,” she replies.

—“Well, then on Friday.”

—“Okay,” she says and, with a face radiant with joy, runs away from me.

That was on a Monday. And on Wednesday, April 13, on a gloomy morning, as usual, around half-past seven, I left the house and, instead of walking down Kotovsky Street for a shortcut through a hole in the fence to enter the territory of the furniture factory, I walked along Skhidna Street to go to a store on Kyivska Street and buy some groceries. Just as I stepped onto Kyivska, two men approached me. They asked for my surname. I answered. They immediately told me to get into the car, which was already standing nearby.

—“We're from the KGB, we need to talk to you,” they say to me.

I get into the Pobeda—and soon I'm in one of the KGB offices. The interrogation begins. For now, without paper. They politely ask about this and that and then move on to the leaflets at school. They ask if I gave the leaflet to anyone to read. And then about the leaflets distributed by me and Volodymyr. They say they know everything, that Tarasyuk has confessed to everything. I understand that I can't deny the leaflet from school because it's in the room, so I explain how I got it. But about giving it to the owner of the house and others to read—not a word. True, they don't ask anything about the owner of the house. I stick to my story: I don't know anything else, and I didn't produce or distribute any leaflets with Tarasyuk, although I understand that Tarasyuk has told everything. They say their part, and I say mine. It's already lunchtime. They bring a loaf of bread, about half a kilogram of sausage, and a bottle of lemonade into the office. I eat my lunch in their presence. Again: confess, we just need to know how it all was. We'll figure it out—and you'll be released. There are only two like you in the entire Soviet . And so it went until dusk. In the evening, they take me to the KPZ (pretrial detention cell). I'm sitting alone in the cell. In the cell, there are bunks, and in the corner, a new galvanized bucket—a slop pail.

The next day, again in the KGB office. Again, the same questions and the same answers. Another night in the KPZ. On Friday, already around noon, I decided to confirm Tarasyuk's testimony. Perhaps this decision was the right one, because although they had no evidence other than Tarasyuk's testimony (we had put them up in gloves), I understood that they had no reason not to believe him. Especially since they had seized the leaflet during the search, which I hadn't handed over to the KGB representative back then. I decided: I must confess. If they release me (they promised), they release me. If not, then maybe I'll get less, taking into account the confession and repentance. After I confessed, they immediately drew up an interrogation protocol and immediately took me to prison in the Pobeda. They placed me on the ground floor in a small cell with a small table attached to the wall. I already thought that I would be sitting in such a cell. But the next day, they take me up the metal stairs to the third floor of the special block (now those sentenced to life imprisonment are held there), and I enter one of the cells on the left side of the corridor. It is a three-person cell. My metal bed is by the window. It's warm in the cell. The mattress and bedding are fine. There are two men in the cell. Their faces are not like those of people on the outside: somewhat pale with a yellowish tint. It's hard to tell their age. To me, a 20-year-old, they are almost elderly men. One of them is named Isaev, and the other—Mykhalchenko. From Isaev's story, they had arrived from the camps in the North because new cases had been opened against them. They, like me, are under investigation. They have been in the camps for about 15 years. In the past—policemen.

There are books, chess in the cell, and in addition to the food they give three times a day, you can also buy products from the prison commissary. And also receive a food package. Soon, a librarian comes, and I also order a few books. So, one can live: I read books, occasionally play chess with Isaev, and from time to time I am taken to the KGB for interrogations. Although what kind of "case" was it: the investigation ended quickly, and I am waiting for trial. The policemen behave differently. If Isaev is a joker, plays chess, reads books, talks not only about the camps but also about how he burned houses in villages as a policeman, and all this cheerfully, without any sadness, then Mykhalchenko doesn't play chess, doesn't read, doesn't talk about anything, and doesn't ask about anything. He is in some depressed state. There are no emotions on his face. If Isaev asks him something, he will answer with one or a few words, and that's it. Over time, Isaev became insolent.

—“Who do you think you are?!” he says to me. “Our villages were burned, we're facing the firing squad. Why are you here with us?! You've been planted, we'll strangle you at night.”

I had to agree that indeed—who was I compared to them. But I explain that I was not planted. And why I was put with them, I do not know. Mykhalchenko, however, remains silent—not a word from him. It never crossed my mind that Isaev was an informant, that he was reporting to the KGB about Mykhalchenko and me. And how could I think, based on my own case, that anyone would be interested in me, since everything was already known. Mykhalchenko undoubtedly knew who Isaev was, but for some reason, he didn't say a word about it to me. He sat apart from us. Or maybe he was still hoping for something? Once, during another interrogation at the KGB, the investigator, KGB Lieutenant Fomichov, asks me:

—“How are your cellmates, how is it sitting with them? Maybe I should move you to another cell?”

—“It's fine,” I answer him.