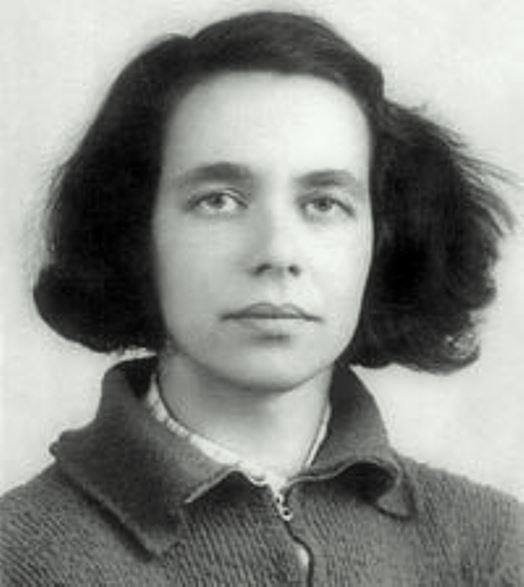

(b. August 8, 1929, Kharkiv, Ukraine - d. April 6, 2004, Moscow, Russia).

Participant in the human rights movement.

Bogoraz’s parents were party and Soviet officials, participants in the Civil War, and members of the CPSU. In 1936, Larisa’s father, Iosif Aronovich Bogoraz, was arrested and convicted on charges of “Trotskyist activities.” In 1947, Larisa went to join her father in exile, against her mother’s wishes.

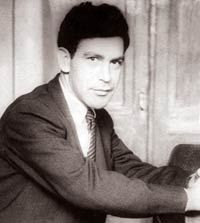

In 1950, after graduating from the philological faculty of Kharkiv University, Bogoraz worked for several months in a rural school as a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature. She then married Yuli Daniel and moved to Moscow. Until 1961, she worked as a Russian language teacher in schools in the Kaluga Oblast and later in Moscow. From 1961 to 1964, she was a postgraduate student in the sector of mathematical and structural linguistics at the Institute of the Russian Language of the USSR Academy of Sciences, working in the field of phonology. From 1964 to 1965, she lived in Novosibirsk, teaching general linguistics at the philological faculty of Novosibirsk University. In 1965, Bogoraz defended her candidate’s dissertation (in 1978, by decision of the Higher Attestation Commission (VAK), she was stripped of her academic degree; in 1990, the VAK reviewed its decision and reinstated her degree as a Candidate of Philological Sciences).

Bogoraz knew about the “underground” literary work of her husband and Andrei Sinyavsky; in 1965, after their arrest, she, along with A. Sinyavsky’s wife Maria Rozanova, actively contributed to shifting public opinion in favor of the arrested writers. The Sinyavsky-Daniel case marked the beginning of systematic human rights activism for many who took part in it, including Bogoraz herself.

From 1966 to 1967, Bogoraz regularly traveled to the Mordovian political camps to visit her husband, where she met the relatives of other political prisoners and introduced them into the circle of the Moscow intelligentsia. Her apartment became a kind of “transit point” for relatives of political prisoners from other cities traveling to Mordovia for visits, and for the political prisoners themselves returning from the camps after serving their sentences.

Many Ukrainian Sixtiers and their relatives passed through her apartment. Bogoraz was friends with several Ukrainian prisoners of conscience and regularly wrote to them in the camps—in Ukrainian, of course. Her relationship with Ivan SVITLYCHNY and Leonida SVITLYCHNA was particularly close. Their families became friends in the late 1950s when Yuli Daniel was translating the poems of Ukrainian poets into Russian. Bogoraz translated many documents of Ukrainian samizdat into Russian before they were sent to the West. Later, it was she who brought out information from a visit with Anatoly Marchenko about a hiding place where issues of the “Ukrainian Herald” prepared by Stepan KHMARA, and Oles and Vitaliy SHEVCHENKO were hidden. She then traveled to Lviv and gave them to Olena ANTONIV.

In her appeals and open letters, Bogoraz was the first to raise the issue of contemporary political prisoners before the public consciousness. After one such appeal, the KGB officer who was “handling” the Daniel family stated: “We have been on opposite sides of the barricade from the very beginning. But you were the first to open fire.”

These years were a period of consolidation for many previously disparate opposition groups, circles, and simply friendly companies, whose activity began to grow into a social movement later called the human rights movement. Thanks in no small part to Bogoraz’s “camp-related” contacts, this process quickly expanded beyond a single social group—the Moscow liberal intelligentsia. One way or another, she found herself at the center of events.

A turning point in the formation of the human rights movement was the appeal by Bogoraz (together with Pavel Litvinov) “To World Public Opinion” (January 11, 1968)—a protest against the gross violations of legality during the trial of Alexander GINZBURG and his comrades (the “trial of the four”). For the first time, a human rights document appealed directly to public opinion; even formally, it was not addressed to any Soviet party or state authorities, nor to the Soviet press. After it was broadcast many times on foreign radio, thousands of Soviet citizens learned that there were people in the USSR who openly advocated for human rights. Dozens of people responded to the appeal, many of whom expressed solidarity with its authors. Some of these people became active participants in the human rights movement. For example, influenced by it, L. TYMCHUK and Viktor and Kateryna Kriukov from Odesa protested the trial. The latter took the protest to Bogoraz in Moscow, but on their way back, they were searched, and a large amount of samizdat literature they had received from her was confiscated.

Bogoraz’s signature also appears on many other human rights texts from 1967-1968 and subsequent years.

Despite objections from many well-known human rights activists (which amounted to the argument that as a “leader of the movement,” she should not expose herself to the danger of arrest), on August 25, 1968, Bogoraz took part in the “demonstration of the seven” on Red Square. She was arrested and sentenced under Articles 190-1 and 190-3 of the RSFSR Criminal Code to 4 years of exile. She served her term in Eastern Siberia (Irkutsk Oblast, village of Chuna), working as a rigger at a woodworking plant.

After returning to Moscow in 1972, Bogoraz did not directly participate in the work of the then-active dissident public associations (only in 1979–1980 did she join the Committee for the Defense of Tatyana VELIKANOVA). However, she continued to occasionally launch important public initiatives, either alone or in co-authorship. For instance, her signature is on the so-called “Moscow Appeal,” whose authors, protesting the expulsion of Alexander Solzhenitsyn from the USSR, demanded the publication of “The Gulag Archipelago” and other materials testifying to the crimes of the Stalinist era in the Soviet Union. In her individual open letter to the chairman of the KGB of the USSR, Y. V. Andropov, she went even further: noting that she did not expect the KGB to voluntarily open its archives, she announced her intention to collect historical data on the Stalinist repressions independently. This idea became one of the impulses for the creation of the independent samizdat historical collection “Pamyat” (“Memory”) (1976-1984), in which Bogoraz took a discreet but quite active part.

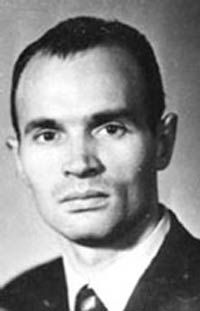

Occasionally, Bogoraz published her articles in the foreign press. For example, in 1976, under the pseudonym “M. Tarusevich,” she published (in co-authorship with her second husband, Anatoly Marchenko) an article in the magazine “Kontinent” titled “The Third Option,” dedicated to the problems of international détente. In the early 1980s, her call for the British government to treat imprisoned terrorists of the Irish Republican Army more humanely sparked a public debate.

Bogoraz repeatedly appealed to the USSR government to declare a general political amnesty. The campaign for the amnesty of political prisoners, which she began in October 1986 together with Sofiya Kalistratova, Mikhail Gefter, and Alexander Podrabinek, was her last and most successful “dissident” action: the call for amnesty by Bogoraz and others was this time supported by a number of prominent figures in Soviet culture. In January 1987, M. Gorbachev began to release political prisoners. However, Bogoraz’s husband, A. Marchenko, did not live to benefit from this amnesty—he died in Chistopol Prison in December 1986.

Bogoraz’s public activities continued during the years of perestroika and post-perestroika. She participated in the preparation and work of the International Public Seminar (December 1987); in the fall of 1989, she joined the restored Moscow Helsinki Group and for some time was its co-chair; from 1993 to 1997, she was a board member of the Russian-American Project Group on Human Rights. From 1991 to 1996, Bogoraz was the head of an educational seminar on human rights for public organizations in Russia and the CIS.

Bogoraz is the author of a number of articles and notes on the history and theory of the human rights movement. In her final years, she worked on her memoirs and edited many “memorial” texts.

She passed away on April 6, 2004, after a long and serious illness.

Bibliography:

Alekseeva, Lyudmila. Istoriya inakomysliya v SSSR. Noveyshiy period [The History of Dissent in the USSR: The Newest Period]. - Vest. Vilnius - Moscow (VIMO), 1992 (first ed. 1984). - pp. 204-207, 207, 213, 298.

Tabirna madonna. Avtonekroloh [Camp Madonna. An Auto-Obituary]. - Dzerkalo tyzhnia, No. 16 (491), 2004. - April 24.

Mizhnarodnyi biohrafichnyi slovnyk dysydentiv krain Tsentralnoi ta Skhidnoi Yevropy y kolyshnoho SRSR. T. 1. Ukraina. Chastyna 1 [International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe and the former USSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1]. - Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny,” 2006. - pp. 75-78.

Rukh oporu v Ukraini: 1960 - 1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk [The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960 - 1990. An Encyclopedic Guide] / Preface by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. - Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010. - pp. 81-82; 2nd ed.: 2012, - pp. 90-91.

Alexander Daniel, Yevhen Zakharov. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Final reading August 2, 2016.