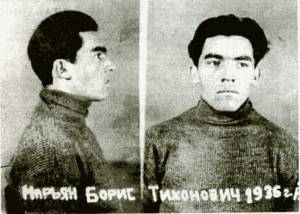

MARIAN, BORYS TYKHONOVYCH (Mold. Marian Boris, born September 27, 1936, in the village of Krasnohorka, Tiraspol Uyezd, Moldavian ASSR – now the unrecognized PMR – Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic).

One of the very first of the Sixtiers, a poet, translator, publicist, and public figure.

Born into a Moldovan peasant family on the left bank of the Dniester. His father participated in the anti-Bolshevik movement, was imprisoned in the 1930s, and served a sentence on the White Sea–Baltic Canal as an opponent of collectivization. In 1944, he was repressed on charges of collaborating with the Romanian authorities and served 10 years in Siberian camps. His brother, Oleksandr, however, was a Komsomol member, a communist, and the chairman of a kolkhoz. His sister, Anna, began teaching in 1947 in the village of Taraclia, Căinari Raion (now the Republic of Moldova), where Borys and his mother also moved in 1948. He completed the 10th grade there in 1953. From an early age, he was drawn to literary creativity, published poems in district newspapers, and decided on his profession early on: journalism.

In 1953, Marian successfully passed the entrance exams to Chișinău University, but upon learning that a faculty of journalism had opened at Kyiv University, he petitioned the USSR Ministry of Education for a transfer to KSU. By order of the USSR Minister of Education, he was enrolled in the first year without competition and was provided with a place in the dormitory. Since most subjects were taught in Ukrainian, Marian, with the help of his classmates, quickly mastered the Ukrainian language and studied Ukrainian history and culture. He focused entirely on his studies, was noted for his diligence, and spent his time outside of lectures in the library reading room. After the first semester, he was already an excellent student. He was sociable, witty, and cheerful. He wrote poems and short stories, worked on the historical drama “Alexandru Lăpușneanu,” and kept a diary. He contributed to the several-meter-long wall newspaper “Linotype,” which people from the city also came to read.

In March 1956, students, pulled from their lectures, were read the four-hour report by the First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, N. S. Khrushchev, at the 20th Congress, “On Overcoming the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences,” in the KSU assembly hall. The report caused an uplift among the young people, raising hopes for the democratization of society. Free-thinking youth discussed various options for social reconstruction without much concealment. But reality quickly cooled their enthusiasm. The suppression of the mass anti-communist movement in Poland was a shock, and especially the bloody crackdown on the Budapest uprising from November 4 to 11, 1956.

The most complete set of pressing issues was laid out by the fourth-year student Marian in his handwritten “Minimum Program for the Democratic Reconstruction of Society.” Here are its main points:

1. Eliminate the caste system and privileges of CPSU members.

2. Declare bureaucracy a criminal offense and wage a merciless fight against it.

3. Reorganize the Komsomol, giving it state functions.

4. Strengthen and expand the sovereignty of the republics.

5. Grant peasants land from one to three hectares.

6. Transfer management of factories and plants to elected workers' committees.

7. Reduce taxes on peasants by half and on workers and the intelligentsia by a quarter.

8. Permit mass rallies, demonstrations, meetings, and other forms of citizen expression, except for armed revolts.

9. Reduce the army to a reasonable size.

10. Limit the powers of the prosecutor's office.

11. Create councils of assessors in courts and grant them broad powers.

12. Publicize the materials of secret and publicly incomprehensible court cases from the Stalinist era.

13. Abolish censorship.

14. Grant the periodical press the right to publish different points of view on problems of economic and state improvement.

15. Do not persecute for the propaganda of different philosophical, aesthetic, and legal views, except for overtly nationalist and fascist ones.

16. Allow the distribution and sale of foreign books, newspapers, and magazines.

17. In international life, continue the struggle for peace and cooperation with all countries of the world.

18. Introduce the practice of broad glasnost for all government negotiations and agreements.

19. Allow free exit from and entry into the country for all citizens who wish it.

20. Grant complete autonomy to universities.

21. Provide students with a stipend that would guarantee an average standard of living.

Being a self-critical person, Marian gave the “Minimum Program” to several classmates to read in mid-December 1956 for their comments. One “honest and principled” female classmate showed due “vigilance” and reported Marian to the university's party committee. The next morning, Marian was summoned to the party committee. There, he was asked to show the “secret document.” The student took the “Program” out of his suitcase and placed it on the table, explaining that it was the first draft of a letter to the CPSU Central Committee, written to help the party democratize society and raise the Soviet people's standard of living to world standards.

The “Minimum Program” came to the attention of Oleksiy Kyrychenko, then the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. He ordered the repressive organs: “Get to the bottom of it!” A lengthy denunciation from the secretary of the course’s party bureau, M. Chornyi, about Marian's notebook of poems also arrived at the KGB. The faculty leadership sent a memorandum to the rector of KSU, proposing to expel student Marian “as a person ideologically immature and unprepared to fulfill the honorable duty of a Soviet journalist.” On December 28, 1956, the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR opened a criminal case against Marian. The rector of KSU, Academician I. T. Shvets, by order of January 4, 1957, expelled Marian from the university as someone who had “disgraced the high title of a Soviet student.” Marian was removed from various records and was preparing to go to the Virgin Lands.

But on January 7, 1957, the party committee organized a meeting of the party-Komsomol activists, which was attended by responsible officials from the Central Committee of the CPU and the Ministry of Education. The tone was set by V. Ruban, the secretary of the journalism faculty’s party bureau: “Marian and his like-minded associates have fallen prey to our enemies. There is no place for such anti-socialist, counter-revolutionary elements in the university. And certainly not in the Komsomol.”

The party organizer of the course, M. Chornyi, pointed out another “counter-revolutionary”—student Volodymyr Damaskin, who shared Marian's views. Student Ivan PASHKOV from Belgorod Oblast and V. Damaskin tried to defend their friend, but Rector Shvets declared: “This rot must be decisively eliminated.”

Meanwhile, during an interrogation by KGB investigator Zhylenkov, the dean of the faculty stated: “I consider it necessary to declare that Marian must be immediately isolated, as his presence at the university has a corrupting influence on the students.”

On January 12, 1957, with the sanction of the Deputy Prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR, Ardyrikhin, a group of operatives arrived at 23:45 at the university dormitory on Solomianka and conducted a search of room No. 28, where Marian lived. They seized 11 manuscripts, including the creative work of the 20-year-old student, namely: the novel “Zelen Dnestr” [“Green Dniester”], the children's story “Tam, gde zvezdy gasnut” [“Where the Stars Go Out”], a general notebook with the inscription on the red cover “Stikhi” [“Poems”], an interlude in six scenes “Dity moi, dity” [“My Children, My Children”], the humorous children's story “Natka-kuropatka i ee bratik Vitka” [“Natka the Partridge and Her Little Brother Vitka”], the historical tragedy “Alexandru Lăpușneanu,” the ballad “Pismo prishlo s opozdaniyem” [“The Letter Arrived Late”], a thick notebook with diary entries, prose sketches without titles, and a notebook with various drafts for future works.

At 33 Volodymyrska Street, he was first offered the usual form of self-denunciation: to write an extended autobiography. During interrogations and face-to-face confrontations with his classmates, Marian consistently maintained that he had compiled the package of proposals for the CPSU Central Committee independently, without instigators or co-authors, with the sole purpose of helping the party eliminate shortcomings. The prosecutor, in a gentle, fatherly tone, urged him to name his instigators and accomplices, promising release and placement in a university in the eastern USSR.

The investigation appointed an expert commission to determine the political and ideological essence of the “Minimum Program” manuscript. The experts—Candidate of Philological Sciences V. E. Shubravsky and Candidate of Historical Sciences F. K. Stoyan—assessed the manuscript as a rough draft of recommendations for a partial restructuring of the socio-political order with the aim of improving matters, although they noted that the author belonged to politically immature and naive people who perceive hostile foreign propaganda and provocative rumors.

The experts did not classify his act as a malicious action of an “enemy of the people.” “The manuscript ‘Minimum’ does not contain direct attacks against the Communist Party, the Soviet government, and our people. But objectively, in its content, in its ideological and political orientation, some of its points express an ideology alien to the Soviet system… The author of the manuscript does not have a definite, clearly expressed program. His work is a mixture of various rumors he knows only by hearsay about the ‘abroad’ and slanderous fabrications of the reactionary press and radio about the USSR.”

Regarding his literary works, the reviewer Yu. Skrypnychenko, head of the literature and art department of the newspaper “Kyivska Pravda,” noted the author’s literary and artistic talent but found in them anti-Soviet, counter-revolutionary fabrications, for example: “O, my black-eyed Moldavia! Where are you? You are a small and honest girl, being violated by pot-bellied bureaucrats, legitimized Arakcheyevs and Unter-Prishibeyevs…” And he concluded: “The issue is not in the facts, but in the tendency. And it, unfortunately, in this young man, is counter-revolutionary from beginning to end.”

Both during the investigation and at the trial, which took place on April 25, 1957, the accused Marian conducted himself with dignity and fearlessness. He did not repent for anything and did not grovel before the judges, begging for mercy, but responded with dignity to the falsified accusations: “I admit that some points of the so-called ‘Minimum’ that I compiled contain an ideology alien to the Soviet system and are partially aimed at restructuring the socio-political life of our country, but by this I wanted to improve our society, democratize it, and improve the welfare of the people. In the ‘Minimum,’ I expressed my opinion and my proposals, but I did not engage in their dissemination. The fact that I gave my ‘program’ to friends and some other students, including communists, to read, I do not consider propaganda, as I gave it to them to read so that they could give me their assessment and help me understand these issues…”

The same “gentle” prosecutor from the investigation, at the trial, in a far from fatherly tone, mentioned the kulak grandfather, the counter-revolutionary father, and theatrically concluded the accusation: “And it is not surprising that the scion of this family now sits before us in the dock as an ardent anti-Soviet.” And he demanded a sentence of 8 years of imprisonment for him.

The Kyiv Oblast Court, presided over by Yevtiukhov, following the usual script, stamped the verdict dictated from the upper echelons of power: to imprison Marian for a term of 5 years in corrective labor camps under Article 54, paragraph 10, of the then-joint Criminal Code of the Ukrainian and Moldavian SSR, without deprivation of civil rights.

Marian served his sentence in Mordovia, in the “Dubravlag” camps, including the 5th punishment camp and the 10th special camp with a prison regime. The Ukrainian prisoners accepted him into their community; he also belonged to a youth student society and a literary studio that had its own underground handwritten journal, “Potma” [“Gloom”]. As early as October 1957, he participated in a political strike in the 7th camp, the largest in “Dubravlag” (over 2,000 prisoners), which became a sensation for the Western “hostile” press. Marian does not consider the time spent in captivity as lost: “It was a university of courage and political tempering.”

He was released in 1962, but for a long time, he was not allowed to work in his profession. He worked as a laborer in a factory, then as a trade union methodologist. In 1968, he graduated by correspondence from the Gorky Literary Institute in Moscow.

In 1971, Marian was finally hired as a literary worker in the editorial office of a factory newspaper, later a district newspaper, and worked at the weekly “Cultura Moldovei” [“Culture of Moldova”]. From 1993 to 2001, he was the editor-in-chief of the government newspaper “Nezavisimaya Moldova” [“Independent Moldova”], from 2001 to 2003, the general director of the “Moldpres” Information Agency, and from 2003 to 2009, the editor-in-chief of the illustrated magazine “Moldova.”

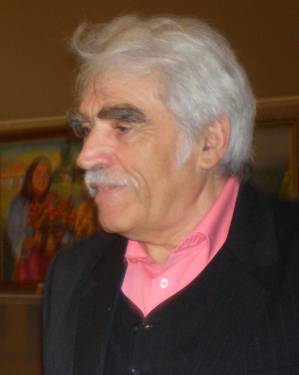

Since 1989, he has been actively involved in political life. He defends the independence and integrity of Moldova, protects the identity of the Moldovan people and their right to statehood. He was rehabilitated in 1990.

He is the author of seven books of poetry in Russian and five books of publicism and children's literature in Moldovan. The poem “Legend of the White Stork” was published in Ukrainian in 2011.

He is a member of the Union of Journalists of Moldova and the writers' unions of Moldova and Russia.

He was awarded the medal and order “Hungarian Revolution of 1956” (1996 and 2006). In Hungary, he met with President Árpád Göncz, a former political prisoner. He is a laureate of the National Prize in the field of publicism (1977 and 2001). He is a Knight of the highest state award, the “Order of the Republic” (2006).

Marian maintains constant literary and personal ties with his friends in Kyiv. For example, in May 2003, he came to Kyiv for the 45th anniversary of his classmates' graduation from the faculty of journalism, and in 2012, he met with his colleagues at the Ukrainian Culture Foundation, where he presented a new book of poems and memoirs, “Nit moey Ariadny” [“My Ariadne's Thread”], and the trilingual poem “Legend of the White Stork.” In the same year, he had a creative meeting and held a master class with students of the Institute of Journalism of the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv.

He lives an active public life in Chișinău, collaborates with the Ukrainian diaspora and with the International Non-Governmental Organization “Dialogue-Eurasia,” and publishes articles in Moldova, Ukraine, Russia, Turkey, and Romania.

Bibliography:

1.

Boris Marian. Naedine so vsemi. Izbrannye stikhi [Alone with Everyone. Selected Poems]. (Preface by Kirill Kovaldzhi). Chișinău, 2006. – 248 pp.

Boris Marian. Nit moey Ariadny. Kniga stikhov i memuarov [My Ariadne's Thread. A Book of Poems and Memoirs]. Ch.“Combinatul Poligr.”, 2011. – 220 pp.

Boris Marian. Legenda berzei albe = Opovid pro biloho leleku = Skaz o belom aiste (Poem romantico-istoric) [Legend of the White Stork] / Chișinău, 2011 (Ed. “Elan poligraf” SRL) – 72 p.

2.

Musienko, Oleksa. “Shistdesiatnyky: zvidky vony?” [“The Sixtiers: Where are They From?”] // Literaturna Ukraina. – 1996. – November 21. https://museum.khpg.org/1203762120=

KHPG Archive: Interview with H. Hayovyi, June 16 and 29, 1999. https://museum.khpg.org/1120845382=

Yarmysh, Yu. F. Kyivskyi natsionalnyi universytet imeni Tarasa Shevchenka: 170 rokiv diialnosti [Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv: 170 Years of Activity]. – Electronic Library of the Institute of Journalism: http://jornlib.univ.kiev.ua/index.php?act=article&article=1322

Hryts Hayovyi. Postament dlia pamiatnyka z okrushyn navkolorodynnoi ta kolezhanskoi khroniky v avtorskii redaktsii [A Pedestal for a Monument from Crumbs of Family and Colleague Chronicles in the Author's Edition]. – K.: Hart, 2007. – pp. 16 – 17.

Borys Oliynyk. “Podvyzhnyk” [“The Ascetic”] (Preface to the book “Opovid pro Biloho Leleku” [“Legend of the White Stork”]).

K. Kovaldzhi. “Sedmaia raduga Borisa Mariana” [“The Seventh Rainbow of Boris Marian”] (Preface to the book of poems and memoirs “Nit moey Ariadny” [“My Ariadne's Thread”]).

V. Lupashko-Muzychenko. “Dobra liudyna z Kyshynova” [“A Good Person from Chișinău”] (Article about the author in B. Marian's book “Opovid pro Biloho leleku” [“Legend of the White Stork”]).

Mikhail Lupashko. “Boris Marian: ‘Ya ostaius moldavaninom i gosudarstvennikom’” [“Boris Marian: ‘I Remain a Moldovan and a Statesman’”]. Weekly “Ekspert novostey” (Chișinău), Sept. 12, 2011, and also: Enews.md 24.09.2011. http://ava.md/society/012785.html

Interview with B. Marian, September 25, 2012: https://museum.khpg.org/1360179804

Stanislav Hryhorenko. “Chest i hidnist pokolinnia” [“The Honor and Dignity of a Generation”] (“Ukrainska Literaturna Gazeta,” No. 21, October 19, 2012).

Svetlana Prokop. “Vekhi sudby” [“Milestones of Fate”] (journal “Russkoe pole,” Chișinău, No. 3, 2012).

International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny.” – 2006. – 1–516 pp.; Part 2. – 517–1020 pp.; Part 3. – 2011. – p. 1021 – B. Marian: pp. 1206 – 1210: https://museum.khpg.org/1203762975

Rukh oporu v Ukraini: 1960 – 1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk [Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960–1990. An Encyclopedic Guide] / Preface by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. – K.: Smoloskyp, 2010. – 804 pp., 56 ill. (B. Marian: pp. 416-417; 2nd ed., 2011. – pp. 467-468).