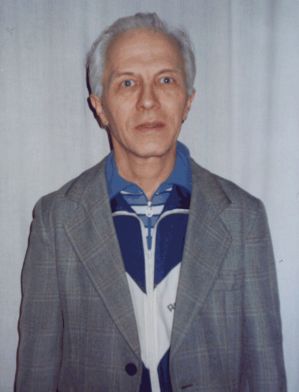

PAVLOV, VADYM VASYLOVYCH (born August 21, 1951, in Kyiv)

Dissident, political prisoner, victim of punitive psychiatry.

His father, Vasyl Illich Pavlov (1925–1961), was from Russia, a war veteran who worked as an equipment test mechanic at a military plant. His mother, Olha Adolfivna Savost (b. 1924), was of partial Swedish, French, and Cossack descent. In 1941, when the massacres at Babyn Yar began, she saved a Jewish woman at the risk of her own life. In 1942, she was taken to Germany for forced labor and was liberated by the Americans in April 1945. For two years, she was not granted a residence permit in Kyiv. When she lost her passport in 1950, the NKVD accused her of being a Swedish spy who had sold her passport to the Swedes (her passport listed her nationality as Swedish). Fortunately, a kind person found her passport.

Vadym’s character was influenced by his grandfather, Adolf Vilhelmovych Savosta (1891–1963)—a decorative artist from Stockholm, a veteran of World War I who served in the army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, and was briefly arrested in 1937. His other grandfather, Illia Pavlov, a train engineer, said in 1933: “How can it be that people are dying of hunger while we are exporting and selling grain abroad?” He was arrested and disappeared without a trace.

Vadym had poor health from a young age, so he started school at eight and graduated in 1969. The school was Russian-language, but his mother read him Ukrainian fairy tales, and they had a copy of “Kobzar” at home. He read a lot on his own—in both Russian and Ukrainian. He attended an archaeology club at the Palace of Pioneers, where he developed an interest in ancient history, archaeology, and later, philosophy. In the club, he met Leonid Zalizniak (later a professor and doctor of historical sciences) and Maryk Horovsky, whose parents had been repressed during the Stalinist era. The club was led by archaeologist Vladyslav Mykolayovych Hladylin, a man with democratic views.

As a child, his mother told him about the famines of 1932-33 and 1946-47 and about the repressions. In the 1960s and 70s, he listened to Voice of America and Radio Liberty. He wrote critical poems (in Russian) and read them to his friends and mother.

As a tenth-grader, he took the suppression of the “Prague Spring” to heart, which happened on his 17th birthday. He went to Khreshchatyk Street, hoping someone would be protesting so he could join them. He wrote a poem about these events and read it to his friends. He wanted to create a circle or organization to actively oppose the government but could not find resolute like-minded individuals. Pavlov first came with friends to the Shevchenko monument on May 22, 1969.

In the autumn of 1969, he was drafted into the army. He trained at a school for junior aviation specialists as an aircraft electrical equipment mechanic and served in the Kaliningrad oblast. There, he developed a stomach ulcer.

He was demobilized in November 1971. He worked as a laboratory assistant in the social sciences office at Kyiv Medical College No. 4 in Darnytsia (for 65 rubles a month). Although he was interested in philosophy, he understood that at the philosophy faculty, he would have to study and later teach Marxism-Leninism. Therefore, in 1972, he enrolled in the correspondence department of the History Faculty at the Taras Shevchenko Kyiv State University.

In January 1972, he heard on Radio Liberty, Voice of America, and the BBC that arrests of Ukrainian intelligentsia had begun, but he found no connections with anyone. On May 22, 1972, he witnessed people being seized near the Shevchenko monument for attempting to speak out.

Pavlov managed to read some of Stalin’s works, including “On the Foundations of Leninism,” which stated that with the construction of a classless society and the abolition of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the communist party would wither away, and all power would be transferred to the people. He found confirmation of this in Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Meanwhile, in the speeches of Brezhnev and the articles of Suslov, it was asserted that the role of the communist party would grow stronger as communism was being built. In 1973, Pavlov wrote a letter to the Institute of Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the CPSU asking them to explain this contradiction.

He was summoned to the city party committee, but they could not explain anything. After some time, a letter arrived from the Institute of Marxism-Leninism stating that the leading role of the party was growing because the struggle against international imperialism was intensifying, and it was necessary to help other countries fight for socialist transformations.

In January 1974, Pavlov was summoned to a medical commission through the military enlistment office. A psychiatrist was particularly interested in him. From there, he was sent to a psychiatrist in the Moscow district. Dr. Zhadanova referred him to a psychoneurological dispensary in Darnytsia. Dr. Kryzhanivsky sent him for an examination at the Pavlov Kyiv Central Psychiatric Hospital. Professor Baron refused to provide such consultations. It was clear that no one wanted to take responsibility for a final diagnosis for Pavlov. He was examined by Professor Polishchuk, Dr. Kryzhanivsky, and another “psychiatrist” whose epaulets were visible under his white coat. The professor found no mental deviations in Pavlov and advised him to take an academic leave, get treatment, and rest. But in the military enlistment office, his military ID was noted: “By the medical commission of the Moscow District Military Commissariat of Kyiv on February 11, 1974, recognized as unfit for service in peacetime. In wartime, fit for non-combat service under Art. 8-B, gr. 1/224, 1966.”

Thus, Pavlov was placed on a psychiatric register. He was periodically summoned to see a psychiatrist. He complained to the Ministry of Health of Ukraine and sent letters to the newspapers “Pravda” and “Izvestia,” to the Central Committee of the CPU to V. Shcherbytsky, and to the Central Committee of the CPSU to L. Brezhnev. These letters were forwarded to local authorities, and Pavlov was summoned for discussions at the city party committee, but never to the KGB.

In February 1974, a psychiatric paramedic named Voziyan came to him and said: “If you keep writing, they will lock you up in a psychiatric hospital. You’d better stop all this because you won’t achieve anything, you’ll only make it worse for yourself.” Pavlov went to Moscow hoping to meet a foreign journalist near the U.S. embassy but did not find anyone. He was again summoned to the city party committee, where this time a detailed file was compiled on him.

After his first year, Pavlov took an academic leave and never returned, realizing that he would not be allowed to finish the university and that he could not work against his conscience. In the summer of 1974, he sent a statement to the university rectorate requesting to be expelled from the university because his views were not Marxist-Leninist.

It was awkward to continue working in the social sciences office of the medical college, so in September 1973, he got a job as a film developer at the Kyiv Film-Copying Factory. In August 1973, he submitted applications to the Moscow district Komsomol committee in Kyiv and to the Central Committee of the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League (VLKSM), stating that he was leaving the Komsomol because he did not consider Marxism-Leninism to be the truth and did not believe in the possibility of building communism in the USSR or anywhere else. He received no reply. He was officially expelled from the VLKSM in 1975. He continued to write critical letters to newspapers and party and state institutions, particularly about the excessive praise of L. Brezhnev. Hearing on foreign radio about the arrest of Sergei KOVALYOV, he sent a protest to the prosecutor of Lithuania. When A. SAKHAROV was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, he sent him a congratulatory postcard addressed to the USSR Academy of Sciences. He wrote letters in support of Mustafa Dzhemilev and Mykola RUDENKO, but had no contact with any dissidents.

When the Jewish movement for emigration from the Soviet Union began, Pavlov decided to try to leave for Sweden, as his grandfather was from Sweden. He applied to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, stating that in the USSR he could not freely study history, criticize Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin, or publish religious poems and critical articles. He thought that perhaps from Sweden he could help democratize Soviet society. At the Kyiv VVIR (Department of Visas and Registration) at the end of 1974, he was told that he had no close relatives in Sweden and would not be allowed to leave without his mother because he was on the psychiatric register. His mother had no intention of leaving.

On the eve of the signing of the Helsinki Final Act of the CSCE, on July 29, 1975, Pavlov declared a protest hunger strike and strike over the violation of human rights in the Soviet Union. In a letter to the Central Committee of the CPSU, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, and to newspapers, he wrote about the persecution of well-known people and himself. On the third day of the hunger strike, the party organizer from the Kyiv Film-Copying Factory came to him and said: “These are your personal affairs. When we go to work, nobody asks if we've eaten or not, so you must come to work, and if you don't, we'll fire you for absenteeism. And it will be with such an entry in your record that you'll never get a job anywhere.” Pavlov said he would continue the hunger strike for now. A few hours later, an ambulance arrived. They threatened to take him to the “Pavlovka” (psychiatric hospital) and demanded he stop the hunger strike. The next day, Dr. Zhadanova came and said: “You won't achieve anything. They'll take you away anyway, they'll inject you, force-feed you, and you'll only ruin your health.” She invited him for an appointment. Pavlov went with his aunt. They called an ambulance and took him to “Pavlovka,” to the rehabilitation ward. They injected him with some drugs. They forced him to swallow pills that caused lethargy, drowsiness, and apathy. He was released under his aunt's custody.

On July 29, 1976, in protest against political arrests, Pavlov sent a statement to the Kremlin renouncing his Soviet citizenship. At the VVIR, they explained that he had no serious reasons to renounce his citizenship.

That same year, Pavlov managed to read the New Testament. It made a great impression on him, and he began writing poems on religious themes. He sent them to the journal of the Kyiv Metropolitanate. After a second inquiry, he was summoned to the State Committee for Publishing, and only after that did he receive a letter from the metropolitanate stating that their journals do not publish poems.

At the end of 1976, when information about the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group began to spread on Western radio stations, Pavlov wanted to join these people but could not find any contacts. He wanted to go to M. RUDENKO in Koncha-Zaspa, but he was soon arrested.

In August 1976, Pavlov quit his job at the film-copying factory, believing that where there are no rights, there can be no obligations to the state. For some time he did not work, instead writing letters and petitioning to renounce his citizenship and emigrate.

In 1977, he submitted many amendments to the drafts of the constitutions of the USSR and the Ukrainian SSR to the Constitutional Commission and newspapers—proposing a multi-party system, opposing the leading role of the CPSU, supporting the right of republics to freely secede from the USSR with guarantees for agitation for secession, and periodic referendums on secession.

At the end of 1977, he held another protest hunger strike. The district police officer Vasyl Ivanovych Sydorenko summoned him and warned him that if he did not work, he would be punished as a “parasite.” Pavlov explained that he was not a parasite, but was living off his earlier earnings. He had to stop the hunger strike, but a few days later he was again committed to the Pavlov Kyiv Central Psychiatric Hospital, where he stayed for a month. He was released just before the King of Sweden’s visit to Kyiv.

From June 12, 1978, Pavlov worked at the Kyiv Library Collector. Meanwhile, a criminal case had been opened against him under Article 214 of the Ukrainian SSR Criminal Code. At the end of June, Pavlov was summoned to court. The lawyer Indychenko proved that Pavlov could not be punished with imprisonment or sent to forced labor because he was already employed. Nevertheless, he was sentenced to a 20% deduction from his salary for one year. When the document for the salary deduction arrived at his workplace, the management of the library collector became frightened, as the collector also supplied books to the Central Committee of the CPSU, the Supreme Council, and the KGB. But the head of the department, Nina Borysivna Filipova, defended him. While he worked there, he restrained himself from writing, and if he did write critical remarks to newspapers, they were not as harsh. But he had to quit that job too under pressure from the party organizer and the director.

He worked as a loader at a trade union printing house and as a packer at a margarine factory.

In December 1981, when the Solidarity movement in Poland was suppressed and martial law was imposed, Pavlov sent a letter to the Polish embassy and to the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions (VTsSPS) of the USSR, stating that he was leaving the trade union in protest.

In September 1982, he went to Moscow, climbed over the fence of the Austrian embassy at night, waited until morning, and gave an embassy employee an appeal to the participants of the Madrid CSCE Meeting. In the appeal, he cited examples of human rights violations and wrote that the leadership of the USSR could not be trusted. When Pavlov was leaving the embassy, he was detained by policemen and taken to the 60th precinct. He was interrogated and released, possibly so they could follow him to see which dissidents he would go to.

In October–November 1982, Pavlov prepared a letter in which he again wrote that the leading role of the Communist Party should be abolished and the party disbanded, that all power should be given to the Soviets, a multi-party system introduced, and democratic reforms carried out. He wrote all this by hand and sent it to all first secretaries of the Central Committees of the communist parties of the republics, all capital city committees of the republican communist parties, all first secretaries, all heads of the capital republican city councils, the presidiums of the Supreme Soviets, and the newspapers “Izvestia” and “Pravda.”

On the morning of May 19, 1983, Pavlov returned home from the second shift. Two men from the Kyiv City Prosecutor's Office entered his apartment and ordered him to go with them. After an interrogation at the city prosecutor's office, he was taken to the 13th ward of the “Pavlovka” for a forensic medical examination. He remained there until August 1. During this time, he had three different doctors—it seemed no one wanted to take on this uncertain case. It was precisely at that time that the World Psychiatric Association in Honolulu, Hawaii, condemned the use of psychiatry for political purposes in the Soviet Union. The Soviet psychiatrists then withdrew from the Association to avoid being expelled.

Pavlov was transferred to the Lukianivka pre-trial detention center. The cells were overcrowded, with two-tiered bunks, and there was no free space. Pavlov admitted to being the author of all the letters but insisted that the Constitution guaranteed the right of citizens to submit applications, complaints, and proposals to all government bodies and the press, and that his letters were not distributed in samizdat (at least there was no such evidence; witnesses only testified that he listened to Western “radio voices”). Pavlov refused the services of lawyer V. Lamekin, who did not agree to defend him as completely innocent. But prosecutor Abramenko insisted that the defendant had a diagnosis of “mosaic circle psychopathy” and, although deemed sane, could not defend himself. Before the trial, the defendant was not allowed to review the case or make excerpts. The Code of Criminal Procedure was only given to him after he threatened not to participate in the trial.

On September 6, 1983, the criminal division of the Kyiv City Court (Judge V. Draha, people’s assessors V. Korobova and Ye. Kobzarenko, secretary H. Humeniuk) heard case No. 2-135 on the charge against Pavlov under Article 187-1 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (“Dissemination of deliberately false fabrications that defame the Soviet state and social system”). Prosecutor L. Abramenko, referring to the 1978 conviction, persistently demanded three years of some “special regime,” when only a general regime could be considered, as Pavlov was no longer considered previously convicted, according to Article 55 of the Ukrainian SSR Criminal Code (“Expungement of a conviction”). The prosecutor did not read any quotes from the letters, only accused.

Pavlov’s “slanders” consisted of the following:

“The defendant Pavlov revises the Marxist-Leninist doctrine of building a communist society in the USSR, stating that communism is allegedly a myth in theory and in practice;

claims that the USSR Constitution allegedly entrenches discrimination against the Christian faith;

the mass media of the USSR allegedly ‘disinform’ the masses, praised and justified renegades who were brought to criminal responsibility;

claims that the CPSU has fulfilled its historical mission and should allegedly announce its self-dissolution;

discredits the activities of Soviet law enforcement agencies, claiming the alleged violation of democratic rights and freedoms of citizens in the USSR,” and more.

He was charged with disseminating these ideas from 1976 to 1983 (although he actually started writing in the autumn of 1973). Pavlov did not plead guilty. He was sentenced to 3 years of imprisonment in a general-regime corrective labor colony, with his time in psychiatric examination taken into account.

The Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR upheld the verdict on October 6, 1983: “Pavlov’s sentence was imposed taking into account the increased social danger of the crime committed and data about his personality.” In other words, appealing to Soviet institutions constituted an “increased social danger.”

Pavlov was transported en masse to “institution OR-318/76” in the village of Rafalivka, Rivne oblast. On October 23, 1983, at the “labor force” distribution, the colony chief said that such a malicious anti-Soviet person should be kept “with an iron fist” and threatened him with additional imprisonment under Andropov’s Article 183-3, “Malicious disobedience to the demands of the administration of a corrective labor colony.” Pavlov then refused to enter the zone and declared a hunger strike. He was placed in a punishment cell, left with a zek’s jacket, pants, and slippers. He grew weak and could not lift the bunk to secure it, so he lay on the wooden floor. The zone chief told him that Vasyl BARLADIANU had recently been imprisoned there: “He was finishing his term, but we found witnesses for him and sentenced him again for another three years. The same will happen to you. And what about a hunger strike? No one knows about you. You'll either die here or become exhausted, and we'll send you to the hospital, where we'll feed you with a tube, ruin your health, and you won’t achieve anything.”

After 10 days, Pavlov ended the hunger strike. He spent a few more days in the punishment cell, after which he was sent to the eighth detachment—to assemble crates and repair the premises. He found out that he was initially assigned to the worst, 14th detachment—to quarry granite, where many prisoners died.

The camp was divided into local zones, and the barracks were overcrowded: two-tiered bunks, narrow aisles, and the second shift slept on the first shift’s bunks during the day. The zone chief tried to turn the prisoners against the “anti-Soviet,” but Pavlov had no conflicts. He communicated more closely with Jehovah's Witnesses and Pentecostals, who were mostly imprisoned for refusing to serve in the Soviet army. These included Anatoliy Uhryn, Viktor Dovhan, and Anatoliy Ivashchenko.

From the zone, he continued to write appeals to various authorities, stating that he did not admit any guilt. His mother also sought his release. He was considered for a mitigation of his regime. When the court asked if he would continue to appeal the verdict, Pavlov replied that he would, as he did not consider himself guilty. He was not released. At the end of summer 1984, on the second attempt, after the death of Y. Andropov, the court ordered Pavlov to be sent to a settlement colony.

After a difficult transport, on September 7, 1984, Pavlov arrived with a large group of prisoners at the settlement of Nyrob, Cherdyn raion, in the north of the Perm oblast (Russia)—“institution Sh-320/8-6.” He worked in a logging area as a branch-cutter. The security was not very strict, as there was taiga for hundreds of kilometers around. It was hard to meet the quota, and those who failed were put in an unheated punishment cell. If the plan was not fulfilled, they were forced to work on Sundays as well. Due to the inexperience of the loggers, a tree fell on Pavlov, although it only grazed him with its branches. When he regained consciousness, he had a rapid pulse and breathing. He was taken by draisine to the hospital of a strict-regime zone. An X-ray showed cracked ribs. He couldn’t walk for a month: he was carried out into the corridor for injections because the nurse was not allowed to enter the ward.

Upon his return to the settlement colony, the political officer assigned him to work at the switchboard. When the chief found out, he shouted: “What is this! An anti-Soviet at the switchboard! He’ll listen to all our conversations, know all our secrets. Remove him immediately!”

They made him a messenger, although he walked slowly. Then he measured the cubic volume of timber in wagons—around the clock, sleeping in his spare time. From there too, he appealed his sentence, demanding that the Serbsky Institute rescind his psychiatric diagnosis.

During Gorbachev’s perestroika, the prisoners pooled their money to buy an old TV and closely followed the changes in society. Pavlov wrote to M. Gorbachev, saying that he was imprisoned for things that were now being said on TV and written in newspapers. A chief came from Perm and said: “Well, it's not yet known what will happen with this Gorbachev. And you don’t have much time left until the end of your term, so it’s better not to write anywhere, just sit quietly, and then you’ll go home.”

Towards the end of his term, Pavlov told the special department that he would return to Kyiv. But Kyiv denied him, citing USSR Council of Ministers Resolution No. 737 of August 6, 1985, which prohibited state criminals from residing in Moscow, republican capitals, and port and border cities after release. So he registered for Fastiv. He was released on May 19, 1986.

In Fastiv, he registered but, without a residence permit and housing, he could not get a job anywhere. He found work in Brovary unloading wagons of cement and gravel, but had no dormitory, so he traveled to Kyiv to spend nights with his mother. The police demanded that he leave Kyiv and threatened him with imprisonment under Article 196 of the Ukrainian SSR Criminal Code, “Violation of the passport system rules.” He had to hide. On July 1, 1986, he was summoned to a commission of the Moscow district council and warned to leave Kyiv within 15 days. Then Pavlov himself went to the police to find him a job with a residence permit and a dormitory. After a few months, he was finally registered in a dormitory in Obukhiv, but there was no space there. He commuted to Kyiv every day. Only in the spring of 1988, after earning a good work reference and when perestroika gained momentum, was he registered to live with his mother in Kyiv.

He unloaded bread at a store, worked at a boat station on the Dnieper, and as a loader at the Podilsky department store. He had a stomach ulcer, suffered a rupture in 1990 which led to complications, was treated for a long time, and doctors also diagnosed him with vestibulopathy and deafness in his left ear.

In early 1989, he wrote a letter to the newspaper “Literaturna Ukraina” about the need to create a People's Front. He attended rallies and demonstrations, and started writing articles and poems for newspapers again—this time in Ukrainian, distributing them in manuscript form, and some were published.

Pavlov participated in several congresses and activist meetings of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons, and in the First and Second World Congresses of Political Prisoners in Kyiv. He did not join any political parties due to poor health, but supported the People’s Movement of Ukraine (Rukh) and attended all rallies and pickets. At the reburial of V. Stus, O. Tykhyi, and Y. Lytvyn on November 19, 1989, he carried one of the coffins. That day, he wrote the poem “The Funeral of Heroes.”

He sought rehabilitation, writing that KGB Chairman V. Chebrikov had admitted at a 1988 party conference that there were violations of socialist legality under Brezhnev and Andropov. But the same prosecutor, Abramenko, even in 1990, insisted: “You were convicted correctly. We’ll see what Moscow decides...” He received a document by mail, signed on July 19, 1990, stating that he was rehabilitated by a resolution of the plenum of the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR dated May 11, 1990.

He participated in the “Ukraine without Kuchma” campaign and the “Orange Revolution,” and campaigned for V. Yushchenko, although he has been seriously ill since the summer of 2004: in 2005, doctors diagnosed him with stomach cancer. He underwent a difficult operation and is now a Group II invalid. However, he participates in public life, particularly in the work of the Kyiv Society of the Repressed, and writes to newspapers. He wrote a radio play about the fate of a political prisoner, “Accidental Meeting” (under the pseudonym Vadym Kyy). He is a member of the V. Stus Kyiv “Memorial” Society.

Bibliography:

KhPG Archive: Interview from March 10, 2007.