Translator, author of samizdat and a program for an underground party.

His father, Mykhailo Andriyovych Koroban, born October 7, 1903, from a peasant family in Uman region, graduated from the Bila Tserkva Agricultural Institute and was sent as an agricultural machinery engineer to the northern Altai Krai. His mother, Oleksandra Stepanivna Demchenko, was an actress from a nationally conscious family from Tarashcha region. From Altai, the family moved to Dnipropetrovsk oblast, then to Kherson oblast. They worked at a sovkhoz. In 1935, Andriy’s parents separated. His mother and son moved to the town of Vasylkiv, near Kyiv, where she married a pilot, Oleksandr Mykhaylovych Voronin (who was killed in May 1942).

In 1941, Andriy finished the 3rd grade at school No. 1 in Vasylkiv and went for the holidays to his father in Simferopol, where he had to spend almost the entire war. His father, a candidate member of the Communist Party, did not manage to evacuate and became an active member of the underground organization “Crimean Falcons.” In 1942, his father and Andriy became acquainted with members of the OUN-Melnyk faction, read their literature, and one of them even baptized his little sister. Even then, Andriy began to doubt his Pioneer views and leaned towards the Ukrainian idea. On November 26, 1943, the Gestapo smashed the underground organization; Andriy’s stepmother was shot, and his father went into hiding. Thirteen-year-old Andriy had to care for his 7-year-old sister, partly taking over his father’s underground duties, leading him to a partisan detachment, and becoming a courier. Along with his father, he suffered from frostbite in the partisans, so upon the return of the Reds, he was sent to a hospital in Sochi, where he was treated and trained as a signalman.

In 1944, Andriy passed exams in Simferopol for the lost years, returned to his mother in Vasylkiv, and went into the 6th grade. In 1948, he graduated from the ten-year school with a silver medal and entered the Ukrainian department of the philological faculty of the Kyiv Pedagogical Institute named after M. Gorky. To do this, he joined the Komsomol and in his documents indicated his stepfather, Voronin, because in 1946 his father was imprisoned for 10 years on false charges of collaborating with the German occupiers and the OUN.

In the summer of 1950, Koroban, as a student, worked as a Pioneer leader in the village of Hlevakha near Kyiv. He lived in the apartment of a peasant woman and saw how the peasants were plundered by food taxes and loans. It was then that he discovered the oppressed Ukraine with its songs, customs, and way of life.

That same summer, he went to Crimea and there wrote a long work of 64 notebook pages in the form of a letter to a school friend, Dmytro Bukalo, a law student who had been drafted into the army. In it, Koroban criticized the collective farm system, the electoral system, and Stalin, and wrote that an organization needed to be created to fight. D. Bukalo advised him to give the work to a journalism student, Volodymyr Horbatiuk, to read. He read and praised it, but when Koroban was returning from him on September 20, 1950, a woman at a tram stop near the university supposedly suspected him of stealing a coat and called a policeman. They were taken to the police administration at 15 Volodymyrska Street, searched, and the manuscript was “accidentally” discovered in his bag. They were taken to the KGB at 33 Volodymyrska Street. In Hlevakha and Vasylkiv, Koroban’s notes, letters, and list of addressees were seized.

Dmytro Bukalo was also arrested and brought to Kyiv. During a search of his place, diaries with “anti-Soviet” entries were also found.

In October, Koroban underwent a brief psychiatric examination in Kyiv, and then at the beginning of November, he was transported en masse to Kharkiv. Koroban’s relatives, wishing to “get him out,” testified about his behavior, emphasizing the harsh living conditions and his partisan past. What saved him was that Dr. Papernyi himself read Koroban’s work and concluded that the author was sane: “You come across as such a sociologist in there!”

In early March 1951, Koroban was returned to Kyiv. Investigator Captain Kuznetsov quickly completed the case. In August, Koroban and D. Bukalo were transferred to the Lukianivka pre-trial detention center, where at the end of August, the prosecutor announced the decision of the “Special Council”—10 years of imprisonment in corrective labor colonies under Articles 54-10 and 54-11 of the UkrSSR Criminal Code—“anti-Soviet agitation” and “attempt to create an anti-Soviet organization.” The prosecutor even smiled: “You see, you’ve already served one year.”

The co-conspirators were placed in the same cell and transported together to Gorky. They figured out that V. Horbatiuk had betrayed them.

Koroban arrived at the “Minerallag” administration in the Komi ASSR (“Intaugol”), at camp No. 6. He had the number “G1-703.” The working day there lasted 10 hours. Civilian clothes were forbidden, you couldn’t keep food in the barracks, the windows had bars, the barracks were locked at night, movement was only in groups (even to the toilet), you could only write two censored letters a year, and you couldn’t have paper or a pencil. Koroban harbored incredible escape plans. In the mine, he fell ill with dry pleurisy, and in the hospital, he managed to get transferred to camp No. 3, as it was closer to the railway. He arrived there on September 26, 1952. When the regime eased slightly, Koroban studied German (there were plenty of Germans in the zone) and played the violin. Of the 22,000 prisoners in the camp, half were Ukrainians. Koroban communicated, in particular, with former Ukrainian insurgents. He participated in amateur arts. He met the actress Maria Fedoriak from Drohobych, who had a 25-year sentence but was amnestied in 1954 and traveled around the zones with concerts.

At the end of March 1955, Koroban was sent to Lymyu for logging. There, he was already outside the zone. In the summer, he was returned to camp No. 3. A commission from the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet was already working there to review cases. On August 31, 1956, it released Koroban “with expungement of his criminal record,” which gave him the right to be reinstated at the institute. Koroban argued that his statements against Stalin were milder than the evaluations of him by the June plenum of the Central Committee. The commission itself was surprised that his “organization” consisted of two people.

Koroban returned to Vasylkiv and in September 1956 was easily reinstated at the pedagogical institute, although under pressure from his mother and Maria Fedoriak, whom he married on October 17. Together with his wife, he secured the return of the illegally confiscated house of the Fedoriaks in Drohobych. Therefore, Koroban studied his last year by correspondence at the Ivan Franko Drohobych Pedagogical Institute and received his diploma in 1958. He did not want to teach students a falsified version of Ukrainian literature—his good knowledge of English and German came in handy; he also taught music, singing, and physical education. He corresponded with former fellow prisoners, using other people's and fictional names.

In Drohobych, Koroban wrote a work on sociology. In 1957, he began writing the work “On the Question of the National Independence of Ukraine,” on which he worked for 3 years. He read the works of Hrushevsky, Dontsov, and Vynnychenko.

Meanwhile, a child was born, and his wife, who had already found a place in the Prykarpattia Ensemble, tried to restrain her husband from dangerous activities: In the autumn of 1959, Koroban found a job as a teacher of German and English, music, and singing in the village of Druzhnia, Borodianka raion, Kyiv region. Together with a typist, Olha Yakivna Zvir, he rented a room in the house of the third secretary of the raion party committee at Kladiyevo station. He had a German “Erika” typewriter, on which Olha retyped his work “On the Question of the National Independence of Ukraine” (up to 400 typewritten pages). In this work, Koroban paid great attention to the Princely Era and language.

On December 8, 1960, during a test, Koroban went out into the schoolyard—and was detained by three plainclothes KGB officers. They did, however, allow him to finish the lesson, placing a district education inspector in the classroom. During a search of his residence, the aforementioned typescript was confiscated (they did not find the part “The Language of Kyivan Rus”). He was taken to the regional KGB administration, to General Tikhonov. They arranged a meeting with his father, who had been released after 9 years of imprisonment and rehabilitated, who reproached his son. In this liberal Khrushchev era, it ended with a prophylactic measure: they took a written commitment not to engage in anti-Soviet activities. Koroban explained that he was preparing for postgraduate studies and had become too engrossed in Hrushevsky. He assured them that he had typed the work himself. In doing so, he discovered that a fellow student from the Drohobych Pedagogical Institute, Yevhen Shaban, who had visited him shortly before and seen the typescript, had informed on him.

Koroban did not pass the competition for postgraduate studies. In the absence of Koroban and Olha, whom he had married, KGB officers conducted secret searches of their apartment. However, Koroban believes that from 1961 to 1965, he had a very productive creative period. From 1961, he worked as a teacher in the village of Bronytsia, and in 1966—in the village of Buhayivka, Vasylkiv raion. Based on the section “The Language of Kyivan Rus” and some notes returned by the KGB, he restored the work “On the Question of the National Independence of Ukraine” (about 300 typewritten pages). He wrote a long essay “Shevchenko and Ukraine,” and an economic-sociological work “The Foundations of Marxism and the Essence of Bolshevism.” To gather live material, he traveled extensively throughout Ukraine, and in 1965, he traveled to the Baltics several times. His wife Olha also tried to restrain him from his activities.

To study the social and political situation in the Donbas, in 1966 he left teaching and in August of that year, he got a job as a loader-hauler at the Kirov mine administration in the settlement of Khanzhonkove, near Makiivka. After a few months, he returned to Vasylkiv and got a job as a club manager in the village of Petrushky. Here he wrote the work “Propaganda and Agitation in the System of Russian Pseudo-Socialism, or Bolshevism,” and began to write the program for the “National Liberation Party of the Proletariat of Ukraine.” He gave this work for review to Yevhen PRONIUK, who worked at the Institute of Philosophy of the UkrSSR Academy of Sciences (the work lay with PRONIUK for several months).

Meanwhile, Koroban moved to Kyiv and worked as a molder in the foundry of the “Leninska Kuznia” plant. He later got a job as a translator in an office. In particular, he served an agricultural delegation from the GDR and was supposed to go with them to Germany in September 1969.

To support the activities of the future party, Koroban intended to set up a printing press, collecting parts for a printing machine, and already had a tin of type.

On September 3, 1969, Y. PRONIUK, through Liudmyla Zaviyska, informed Koroban that employees of the Institute of Philosophy had discovered Koroban’s manuscript at his workplace with his, PRONIUK's, comments and had handed it over to the KGB. Koroban went to Vasylkiv. Seeing the KGB officers, he jumped from a roof and escaped. He also met with Ivan DZIUBA, and with the relatives of his wife Olha (they already had a small child), who advised and insisted that Koroban surrender. He gave a list of his works to Y. PRONIUK through L. Zaviyska (it later ended up with the KGB). He also wrote another work and gave it to the Holovchenko brothers in Sumy region. Investigator Mykola Andriyovych Koval left his phone number in Koroban’s apartment, and Koroban spoke with him several times. The investigator asked him to “come and talk, nothing will happen.”

Koroban was in hiding for 8 days. The KGB had information that he had a pistol. Indeed, shortly before this, he had transported a repaired pistol from Vasyl Mytchyn in Drohobych to Oleksa Mykolyshyn in the town of Vyshneve. That’s why they tried to catch him in Babyn Yar as an armed man, but he escaped again. When Koroban himself came to the regional KGB administration on September 11, 1969, investigator Koval first searched him.

The case was handled for 8 months by investigators Koval, Berestovsky, and Slobozhaniuk: 66 interrogations, more than 20 various investigative procedures, 6 face-to-face confrontations.

When the case was almost finished, Pioneer-pathfinders (according to Berestovsky) found a part of Koroban’s work that he had buried under a stump in Zhuliany.

By the verdict of the Kyiv Regional Court on June 1, 1970, Koroban was sentenced under Part 1 of Article 62 and Article 222 of the UkrSSR Criminal Code (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” and “possession of a weapon”) to 6 years in strict-regime camps and 3 years of exile.

On September 9, 1970, Koroban arrived by transport at camp ZhKh-385/19, in the settlement of Lesnoy, Mordovia. His circle of communication included insurgents Ivan POKROVSKY, Vasyl YAKUBIAK, Myroslav SYMCHYCH, Stepan SOROKA, Mykhailo Zelenchuk, and others. Preparing to continue the struggle, he studied the experience of his predecessors, processed literature, and had many notes.

On July 9, 1972, a whole train of political prisoners left the Mordovian camps for the Urals during a great heatwave. On the way, the 25-year prisoner Mykytiuk, whom Koroban knew from Komi, died. Koroban was brought to camp VS-389/35, at Vsesviatska station, Centralny settlement. He worked as a loader and communicated with Ivan SVITLYCHNY, Valeriy MARCHENKO, Yevhen PRONIUK, Zinoviy ANTONIUK, Ivan KANDYBA, Roman HURNYI, Mykhailo DIAK, Volodymyr BUKOVSKY, and Vladimir OSIPOV. He behaved prudently, harboring the intention of emigrating after his release.

On September 5, 1975, Koroban was taken for transport. After 26 days, he arrived in the town of Kargasok, Tomsk oblast—the capital of the Selkups (Ostyaks), on the Ob River. He worked as a stoker in the house of culture, and later as an artist. The ideological department of the raion party committee wanted to remove him, but the director of the house of culture defended him. Letters and packages from France, Italy, and Germany—with books and clothes—arrived for Koroban in exile. Towards the end of his exile, he quit stoking to prepare hay for the landlady with whom he lived. He worked as a watchman.

He was released from exile on July 17, 1978 (it was shortened by the time spent in transit in 1975).

Koroban had no intention of reconciling with the existing system, but he also did not want to return to captivity. Therefore, he set himself the goal of leaving the USSR. He stopped in his native Vasylkiv. He got a job as an artist in the district art workshop. The pay was low, so after 8 months he switched to being a mail car conductor, traveling, in particular, to Simferopol and Kharkiv. When the KGB received information that he was meeting with former political prisoners, in particular, with Ihor KRAVTSIV, he was transferred to a sorter at the railway post office.

Koroban entered into a sham marriage with a Jewish woman, Bronia Shafran, who already had a summons from Israel. Permission from relatives was needed. Koroban’s father, now fully rehabilitated and decorated for his participation in the underground, wrote an angry letter to the VVIR and refused permission. During a conversation with a VVIR employee, Koroban snatched his father's letter—and she did not report it.

At the beginning of 1980, the case was returned from the VVIR without documents, which meant a final refusal. In May 1980, Koroban went to Lviv to say goodbye to his daughter Oksana. They created a scandal for him in a restaurant, and he was arrested for 10 days. The suitcase, left in a luggage locker, was returned by the Vasylkiv district police department a month later. In response to further demands, he was told frankly: “Andriy Mykhaylovych, you are very bothersome. Remember: we will not let you out. Even though you say you will return, we know that if you leave, we will have another cunning and smart enemy there.”

Koroban received a beautiful envelope. Inside—a drawing of a skull and bones. During the 1980 Olympics, the police demanded that Koroban leave Kyiv and the region. Thanks to this, he visited Sumy oblast, Kharkiv, the Donbas, and Fedir Klymenko in Dnipropetrovsk.

The police threatened a case of “parasitism,” but Koroban had already found a job in Vasylkiv as a boiler stoker. He had time there to read and write. He met a typist, Yevhenia Mykhailivna Hoidak, whom he married on July 11, 1981. On November 29, their son Ruslan was born.

For two seasons, Koroban worked as a stoker, one summer at a refrigerator factory in Vasylkiv, and in the autumn of 1982, he moved to the boiler room at “Kyivmetrobud,” where he worked for 12 years, until his retirement in 1994. He tried not to draw attention to himself, but he worked with books and corresponded with people abroad, including Halia Horbach. He took part in the funeral of Valeriy MARCHENKO on October 14, 1984.

In the autumn of 1982, in the boiler room, he wrote a long work, about 100 pages, titled “Observations and a Few Reflections.” It contained real-life negative examples from the refrigerator factory and “Leninska Kuznia,” from mines and collective farms, almost without conclusions. He added quotes from a plenum of the Central Committee and sent the work to Moscow. In December 1983, he was summoned to the Central Committee of the CPU, where a certain Fedorov talked to him for two hours: “Yes, there are many outrages. But we have no national question. In general, thank you for your effort, for providing a picture.”

In 1989, Koroban took an active part in the creation of the Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons, and in the Constituent Assembly on Lviv Square in Kyiv on June 3. He was in the People’s Movement of Ukraine.

In late May 1990, Koroban participated in an international congress of victims of political repression, where he gave a good speech. In the autumn of 1990, he was invited to a meeting of former political prisoners in Leningrad.

In the autumn of 1994, Koroban ran for the Supreme Council of Crimea in the Kyiv electoral district of Simferopol. At that time, the chauvinist press vilified him for his support of the Crimean Tatars, which gave him good publicity.

Koroban currently lives in Kyiv. He is an activist of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons (VTPViR). He has been rehabilitated in both cases.

Bibliography:

Koroban, Andriy. The Last of the Mohicans, or the Irony of Fate // “Za viru i voliu” (newspaper of the Ternopil organization of Christian Democrats), Nos. 2 and 3, 1992.

Koroban, Andriy. 1938–1998. Sixty Years of My Life // “Evreiskie Vesti,” No. ???, 19... year, date. (4 issues).

KhPG Archive: Interview with Andriy Koroban, December 3, 1999.

58-10. Supervisory Proceedings of the USSR Prosecutor's Office in Cases of Anti-Soviet Agitation and Propaganda. March 1953 – 1991. Annotated Catalog. Edited by V. A. Kozlov and S. V. Mironenko; compiled by O. V. Edelman, Moscow: International Foundation “Democracy,” 1999. – 944 p. (Russia. XX Century. Documents)”: – p. 715.

May 10, 2009. Vasyl Ovsiyenko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group.

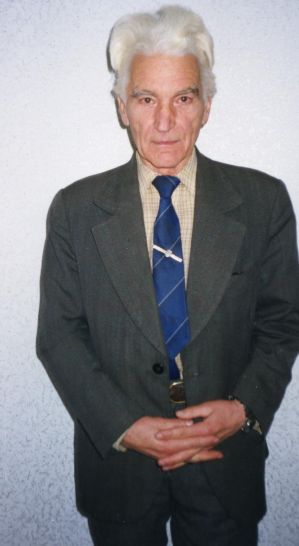

KOROBAN ANDRIJ MYKHAYLOVYCH