OCHAKIVSKY, VILEN YAKOVYCH (born August 29, 1937, in Kherson).

Dissident, human rights activist, subjected to “punitive psychiatry.” Produced and distributed anti-party leaflets. Created a miners’ trade union. Public figure, “Memorial” activist.

His father, Yakiv Isakovych (1901–1979), was a staunch communist, a graduate of a party school, and, as a “twenty-five-thousander,” organized a kolkhoz in the village of Khrestovozdvyzhenka. His mother, Khaia Yankelevna Ostrovska (1905–1982), was a housewife. His brother Roman served in the naval border units of the KGB.

From childhood, Vilen wrote poems in Ukrainian and Russian, was a convinced Leninist, but by the 9th–10th grades, he was asking such questions of both Lenin and his father that his father concluded: “You are a counter-revolutionary. If you weren’t my son, I would turn you in. You’ve been listening to the Voice of America, you’re an anti-Soviet.”

After graduating from secondary school No. 20 in 1955, Vilen tried to enter a military academy to become a counterintelligence officer, but he was not accepted. In 1956, he was drafted into the special communications troops. He served near Odesa as a radio intelligence interceptor, listening in on Americans and Turks. He was valued as a specialist. But in 1958, his questions “cornered” the regimental propagandist. As unreliable, he was removed from the air: “Who knows what he’s listening to there, he knows English, listens to the Americans, has breathed in their hostile spirit, and organizes meetings in the battalion.” He was transferred to the maintenance platoon. But when the regiment received a government task to conduct reconnaissance of Turkish radio-relay lines, there was no other specialist like Private Ochakivsky.

In the summer of 1959, Ochakivsky was demobilized early to enroll in the Odesa Special Secondary School of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs. His entrance essay was read aloud before the ranks as a model. A year later, in May 1960, he was expelled from the police school for a feuilleton titled “School of Thugs,” which he had sent to the magazine “Soviet Militia,” and then to the newspaper “Komsomolskaya Pravda.” The motivation: “For slandering the school’s command, for non-conformity with the image of a Soviet police officer, and for tolerance towards the criminal world.” Thus, for professional incompetence.

In September 1960, Ochakivsky was recruited to Yakutia. He worked for the newspaper “Sotsialisticheskiy Trud” (in the settlement of Mukhtuya, Lensky raion). He wrote an article, “Not Quiet on the Quiet Wharf”—about a strike at the river port, and a courtroom report, “Deprivation of Liberty”—about how a docker, a disabled young man, was tried for slapping a party organizer because he had insulted him during the strike. Of course, the articles were not published, but Ochakivsky considers this the beginning of his human rights activism.

As a gifted leader, he was invited to work in the Lensky district committee of the Komsomol. There, in November 1961, he managed the unheard-of: holding an election with alternative candidates. His “team” turned out to be mostly composed of people from Ukraine. In December, a friend, Stanislav Krasovsky from the Holoprystan raion of Kherson oblast, who worked in the party district committee, advised him to flee, because the KGB had taken an interest in him.

He moved 230 km north, to the settlement of Mirny. As a journalist, he wrote about sports, created a children’s football club focused on the Ukrainian school of football, on “Dynamo,” and in 1974, he took 20 of his protégés to Nova Kakhovka.

As a public defender, he spoke in the case of Nina Bulakh, a Ukrainian from Kuban, who was accused of “theft of socialist property.” The prosecutor demanded 3 years of imprisonment for her, but after Ochakivsky’s speech, the court gave her 2 years probation.

To become a professional human rights defender, in 1962 Ochakivsky enrolled in the law faculty of Irkutsk State University. But he quickly became convinced that a conflict with official legal consciousness was inevitable and left his studies in 1964.

In 1962, he married Halyna Moshkina, a Siberian, honestly warning her that due to conflicts with the authorities, he might end up behind bars. In 1964, their son Fidel was born (in honor of Fidel Castro), and in 1974, their daughter Zhanna (in honor of Joan of Arc).

In 1975, a KGB acquaintance warned Ochakivsky to bury his samizdat (he had P. HRYORENKO’s review of A. M. Nekrich’s book “1941. June 22,” among other things).

In June 1976, Ochakivsky moved to the city of Gorky (Nizhny Novgorod), and as a driver-ferryman, he traveled throughout the European part of the Soviet Union. He intended to write a book.

Meanwhile, his wife exchanged their apartment in Mirny for one in Oleksandriia, Kirovohrad oblast. In January 1978, Ochakivsky moved there as well. For a while, he worked as a driver, but in 1979 he got a job as an underground miner, 3rd grade, at the “Verbolozivska” mine of the “Oleksandriiavuhillia” association. In 1980, he graduated with honors from the Makiivka Mining and Mechanical School with a specialty in MGVM (mining machinery operator), i.e., an underground combine operator, but due to a lack of a combine operator position, he went to work as a tunneler.

He prepared leaflets—anti-Brezhnev, anti-party photo-collages with his own caricatures and poems. A photo-artist, whose name Ochakivsky still does not disclose, helped him. He scattered these leaflets in Donetsk, and in Moscow during the 1980 Olympic Games. One of them read: “Comrades marshals and generals! Officers and soldiers of the Taman and Kantemirovskaya divisions await your command to come to Red Square, surround the Kremlin, and arrest the criminal gang of the Politburo, to bring them to trial in a second Nuremberg process.”

At the beginning of 1982, Ochakivsky began to create an independent trade union. First, he effectively took over the existing trade union at the “Vedmezhiarska” mine of the Mine Construction Administration No. 2 of the “Oleksandriiashakhtovuhlebud” trust. Under his chairmanship, the miners elected a workshop committee at a meeting. Ochakivsky asked for the “portfolio” of editor of the wall newspaper “Na khod!” (a miner’s command for “forward”). But the party organizer tore the newspaper down. So Ochakivsky began to post it underground: the miners read the wall newspaper by the light of their “konogonka” lamps.

Everything was ready for the creation of an independent trade union for the entire mine. It was to be the first independent trade union in the entire Soviet Union (as is known, V. KLEBANOV’s trade union included people who lived all over the USSR). But 6 days before the conference, on October 11, 1982, Ochakivsky was arrested during his work shift. During a search of his home, all his manuscripts were seized, and sealed negatives of leaflets were found between the pages of books. At his dacha in the village of Protopopivka, Oleksandriia raion, investigators dug up his garden in search of “evidence.” A rumor was spread that a spy had been caught, who had a radio station.

Ochakivsky tried to joke that they had arrested Lenin—Vilen, and that the organization “Spartak,” mentioned in the seized papers, was a work of fiction: “Union of Truth-Seekers of the Anti-Brezhnev Revolutionary Fellowship of Anti-Party Communards,” and the leaflets were just illustrations for a book that had not yet been written.

In the first days after his arrest, Zhilenko, the head of the special department at the Oleksandriia auto-repair plant where Ochakivsky's wife worked, told her that her husband was terminally ill and advised her to divorce him. Investigator Valeriy Mykolayovych Karelov ordered a stationary psychiatric examination. He was sent to a special ward of the Odesa regional psychiatric hospital. The examination was conducted by Alla Pavlivna Kravtsova. The chairman of the commission, Joni Iosifovich Maier, carefully studied Ochakivsky’s works and concluded that he was “making a very serious excavation under Marxism-Leninism.” “How could I, a simple miner who wielded a pick and shovel, make an excavation under such a powerful layer?”—Ochakivsky was surprised and regarded this as an interrogation, not an examination, demanding that an interrogation record be kept. Maier threw him out. The examination lasted some 10 minutes, the diagnosis: “continuously progressing schizophrenia, paranoid variant.”

Ochakivsky was returned to the pre-trial detention center of the Kirovohrad KGB. Investigator Oleh Mykolayovych Tumenko sent him for treatment to the Dnipropetrovsk special psychiatric hospital at 101 Chicherina Street on the night of April 2-3, 1983. He was immediately placed in the second ward, in the “nadzorka”—a ward where those who begin to have “blackouts” are held, i.e., with the genuinely ill. The head of the department was Lidiia Oleksiivna Chusovskykh. The treating physician, Liudmyla Andriivna Chinchyk, administered neuroleptics and aminazine to Ochakivsky, which caused him to lose consciousness, his blood pressure to drop, and his urine to be retained. Chinchyk prescribed 5 sessions of “pumping”—injecting fluid into his thigh, which causes excruciating pain. He was so “pumped” with drugs that his daughter did not recognize her father during a visit and cried out of fear.

At the end of 1985, the doctors believed that Ochakivsky could be transferred to a general-type psychiatric hospital, but the KGB detained him for another six months. On April 22, 1986, Ochakivsky was finally transferred to the Kirovohrad regional psychiatric hospital in the settlement of Novyi. On November 27, 1986, he was released. Ochakivsky believes that M. S. Gorbachev and his perestroika saved him.

He could not get a job anywhere because he did not hide that he had been imprisoned under an anti-Soviet article. A friend found him a job.

In 1988, Ochakivsky founded “Memorial” in Oleksandriia, and then the People’s Movement of Ukraine for Perestroika. In January 1989, he went to Moscow for the constituent congress of “Memorial.” There, he went to the editorial office of the newspaper “Komsomolskaya Pravda,” which resulted in journalist Aleksey Novikov publishing an article about him on January 1, 1990, titled “The Incurable Marxist.”

Ochakivsky decided to get rid of the diagnosis of “schizophrenia,” which no political prisoner had yet managed to do. He asked a psychiatrist friend to consult him and simulate a psychiatric examination. He asked the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko to appeal to the USSR Minister of Health, Chazov. He also appealed to friends and well-known people for character references. At the end of May 1988, he was invited for an examination at the Pavlov Psychiatric Hospital in Kyiv. He asked to be placed in the 22nd ward, in the ward for the “violent,” where he spent 35 days. The diagnosis was removed on June 22, 1988.

He returned to the “Vedmezhiarska” mine (where he had been arrested). Under pressure from the workers, the director hired him, but soon regretted it, because when the strikes began, Ochakivsky again became the editor of the wall newspaper and was elected chairman of the strike committee. Moreover, in 1989, the miners nominated him as a candidate for People’s Deputy of the USSR, and in 1990—to the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. But everything was done to prevent his registration.

Relying on the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of May 18, 1981, which concerned criminal prisoners, Ochakivsky obtained a resolution from the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR on May 30, 1990, for rehabilitation due to the absence of a crime in his actions as provided for by Article 187-1 of the UkrSSR Criminal Code. He then appealed to the Deputy Prosecutor General of Ukraine, Volodymyr Hryhorovych Musiyaka, who had previously been the prosecutor of Kirovohrad oblast and with whom he had communicated earlier on the matter of rehabilitation, to help him obtain monetary compensation for his “forced absenteeism,” which lasted 4 years and 1 month. He demanded that the money be paid not by the state, but by those guilty of his imprisonment—from the party organizer to the first secretary of the regional committee. He received (from the state) 16,345 rubles, bought a house, and told his wife: “Halya, this house, its doors must always be open for those who have suffered for the truth. Any political prisoner who appears at our doorstep, you are obliged to welcome him as a relative.”

He retired at the beginning of 1991.

He is actively working in the V. Stus “Memorial” society and in the International “Memorial.” He is perhaps the only person in Ukraine who for some time hosted a Memorial program on local television called “Smoloskyp” (Torch). In 1992, he won a grant from the Soros Foundation for the project “Information Center—Museum of Historical Memory.” With these funds, he published press releases of the local “Memorial” under the title “Byloye i Dumy” (Things Past and Thoughts).

He cherishes the idea of creating a Museum of the History of the CPSU-CPU, which stands for “Punitive Psychiatry of the Soviet Union, the Communist Hell of Ukraine. Address: 101 Chicherina Street.”

He is fundamentally non-partisan, but says he would join a “Party of Truth-Seekers of Ukraine” if one existed.

On a joint initiative with the St. Nicholas Church (UAOC), a memorial “Flame of Memory of Oleksandriia region” is being created in the church courtyard, dedicated to the victims of the communist regime: former political prisoners, participants in the national liberation struggles, prisoners of conscience who suffered for their faith, soldiers of the Second World War and those who died in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Afghanistan, and victims of the Chornobyl disaster.

He lives in the city of Oleksandriia.

Bibliography:

1.

Ochakivsky, Vilen. The Road to Hell. – “Yug” (Odesa regional independent newspaper), April 1993 (three installments).

Interview with V. Ochakivsky from March 8, 2001. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group website: http://museum.khpg.org.

2.

Novikov, Aleksey. The Incurable Marxist. – “Komsomolskaya Pravda,” 1990. – January 1.

Khoroshikh, Gennady. Walesa. – “Zhurnalist” (organ of the Union of Journalists of the USSR). – 1993. – September.

58-10. Supervisory Proceedings of the USSR Prosecutor's Office in Cases of Anti-Soviet Agitation and Propaganda. March 1953 – 1991. Annotated Catalog. Edited by V. A. Kozlov and S. V. Mironenko; compiled by O. V. Edelman, Moscow: International Foundation “Democracy,” 1999. – 944 p. (Russia. XX Century. Documents)”: – Ochakivsky: p.800.

Vasyl Ovsiyenko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group.

November 15, 2008. Corrections by V. Ochakivsky, November 27, 2008.

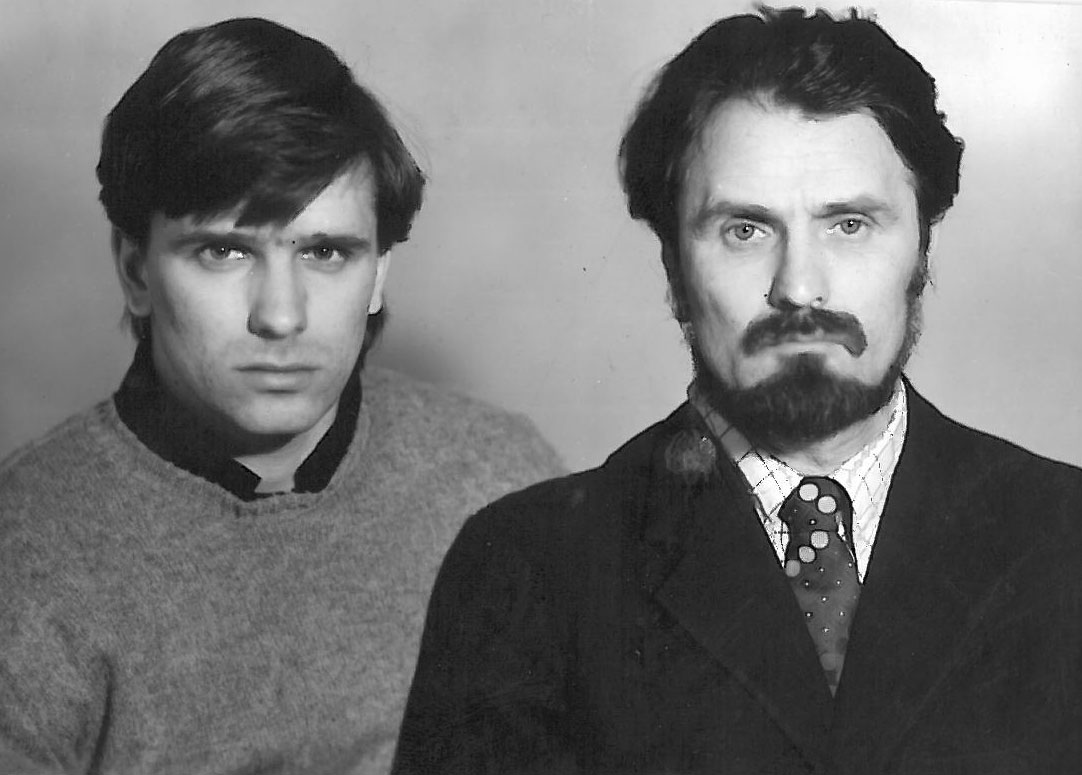

Photos: Vilen Ochakivsky with his son Fidel, 1987 and 1982.