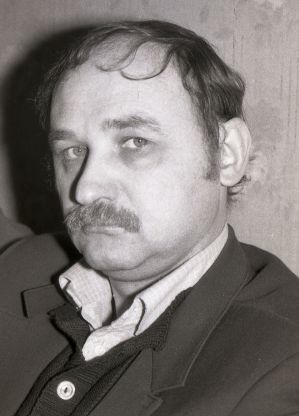

MYKOLA FEDOROVYCH MURATOV (b. November 8, 1950, in the village of Pochinok, Tutayevsky Raion, Yaroslavl Oblast, RSFSR).

Chairman of the Moscow branch of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union (UHU) and representative of the Committee for the Defense of the Ukrainian Catholic Church in Moscow.

His father, Fedir Yakovych Voilenko, was a military builder from the Belgorod region, an area settled by Ukrainians. His mother, Hanna Onykiivna Kuropatkina (née Muratova in her first marriage), came from a family of Belarusian peasants from Mogilev Governorate who had resettled in Siberia during the Stolypin reforms of the early 20th century.

In 1952, his father was imprisoned for 12 years. His wife and two children (Mykola, then 1.5 years old, and his sister Liliya, 6) were evicted from their service apartment, and their property, which consisted of a goat and an ARZ radio receiver, was confiscated. The family wandered through the Belgorod region and on Sakhalin Island before moving in 1958 to Stalino (renamed Donetsk in 1961). Here, Mykola finished secondary school in 1968, worked in a mine, and a year later moved to Moscow, where his sister lived. In 1969, he enrolled in the Faculty of Medical Biology at the Second Moscow Medical Institute, graduating in 1975 with a degree in medical biophysics.

Even in his youth, Muratov was dissatisfied with socialist reality. He began to study Soviet law on his own. He worked as a laboratory doctor at the Central Clinical Hospital of the 4th Main Directorate of the USSR Ministry of Health (the “Kremlin hospital”), rising to the position of head of the hormone department. During the period when the elderly members of the CPSU Central Committee's Politburo were dying off, he joined the religious branch of the human rights movement—the Christian ecumenists. For about two years, they gathered weekly in apartments for prayerful fellowship, discussed general political topics, exchanged *samizdat* and *tamizdat* literature, and read the *Chronicle of Current Events*. In early 1984, several activists of the Christian ecumenist movement were arrested, and their leader, Sandro Ryga, was confined to a special psychiatric hospital. Muratov, under the threat of arrest, was dismissed from his job. Before that, in January 1983, he had been demoted and reprimanded on trumped-up pretexts. For two months, the KGB prevented him from finding any work in his field. Eventually, he was hired at the Research Institute of Human Morphology of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences, where he worked until the summer of 1989.

By mid-1987, many political prisoners had been released, and in Moscow—unlike in the provinces (where there were no permanently accredited foreign journalists or diplomats)—it was now possible to hold public events, at least in private apartments, and to convene press conferences. Ukrainian dissidents also came to Moscow during this time. Muratov became acquainted with Yuriy Rudenko, Vasyl BARLADIANU, and Yosyp TERELIA, and through them, with Vyacheslav CHORNOVIL, Mykhailo and Bohdan HORYN, Pavlo Skochan, Oles SHEVCHENKO, Ivan HEL, Zinoviy KRASIVSKY, and others. It was from his home phone in August 1987 that Y. TERELIA transmitted the “Declaration on the Emergence of the UGCC from the Underground” to the West. The first public appearances of UGCC bishops and priests in their vestments before Western journalists, diplomats, and on television took place in Muratov’s apartment in late 1987.

On December 30, 1987, Muratov, as one of the six members of the editorial board of the journal *The Ukrainian Herald*, which had been revived by V. CHORNOVIL, was co-opted into the Ukrainian Helsinki Group (UHG). He represented the Moscow bureau of *The Ukrainian Herald* as the official publication of the UHG (later the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, UHU).

In January 1988, Muratov traveled to Lviv, which expanded his circle of acquaintances. The chairman of the Committee for the Defense of the UGCC, Ivan HEL, authorized Muratov to represent the journal *Christian Voice* in the Association of Independent Press, which had been founded by Alexander Podrabinek. Muratov, who was well-versed in Soviet religious legislation and international human rights documents, became a legal consultant to the Committee. He provided specific legal assistance to priests and communities of the UGCC in western Ukraine. At that time, his apartment on Oleko Dundicha Street became a headquarters and a hotel, almost like a representative office of Ukraine in Moscow. Here, former Ukrainian political prisoners met with their counterparts from all over the USSR. It was here that M. HORYN introduced Muratov to Paruyr AYRIKYAN and Merab KOSTAVA as a representative of the Working Group for the Defense of Ukrainian Political Prisoners, which was part of the Inter-National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners.

In the summer of 1988, shortly before the millennium of the Christianization of Rus-Ukraine, the Soviet Peace Committee, led by Genrikh Borovik, convened a roundtable with religious dissidents. The Committee for the Defense of the UGCC authorized its legal consultant, Muratov, to speak in defense of the repressed Church. He concluded his five-minute speech by saying: “The UGCC is accused of having not a cross on our Church, but Bandera’s trident. Well, did the comrades want to see the KGB’s ‘shield and sword’ there?” Although Muratov’s speech was not televised like the others, he was summoned by the deputy director of the Research Institute of Human Morphology of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences, where he was then working as a junior researcher. After being asked, “What kind of Church are you defending there?” he was advised to resign “of his own accord,” which Muratov gladly did. After this, when asked by officials where he worked, he would reply, “Nowhere. I am a professional revolutionary.” As an adult, Muratov became a Catholic, as he was not satisfied with the social passivity of Orthodoxy. He considers himself a faithful member of the UGCC.

Muratov considers the most important tasks he had to prepare and technically execute to be: a) the meeting of leading human rights activists with U.S. President Ronald Reagan, who arrived in Moscow at the end of May 1988. This was a de facto recognition of the Ukrainian opposition by both the West and the Soviet authorities; b) the meeting of a UGCC delegation with a Vatican delegation that came to Moscow in the summer of 1988 for the millennium of the Christianization of Rus. This meeting was a de facto recognition of the UGCC, and the issue of legalizing this important national institution was resolved after this meeting. Prior to these events, the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR physically prevented Ukrainian dissidents and UGCC priests from traveling to Moscow if it had information about possible contacts with official figures from the West.

A portion of the humanitarian aid from foreigners and diaspora Ukrainians, as well as uncensored literature, flowed into Ukraine through Muratov. Some Ukrainian dissident authors saw their works, which had been published abroad, for the first time thanks to him.

On the instruction of V. CHORNOVIL, Muratov searched for a lawyer in Moscow to defend Ivan MAKAR, who was accused under Article 187-prime of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (“dissemination of knowingly false fabrications”). Unable to find one, he prepared to defend Makar himself. However, on November 9, 1988, Makar’s case was closed due to the absence of a crime in his actions.

In the summer of 1988, when the authorities were preparing to expel V. CHORNOVIL and M. HORYN from the USSR, Muratov acted as their lawyer, defending them at the Lviv Oblast Prosecutor's Office. At the same time, drawing on Soviet and international legal documents, he drafted a legally sound proclamation on the people’s right to hold rallies and worked on the section of the UHU’s “Declaration of Principles” concerning human rights. Muratov, along with V. CHORNOVIL, visited Zinoviy KRASIVSKY and Ivan SVITLYCHNY in Morshyn, Father Yaroslav LESIV in Bolekhiv, and Yosyf ZISELS in Chernivtsi. Chornovil assigned him the task of creating a Moscow branch of the UHU. Its founding meeting took place in September 1988. At the suggestion of journalist Anatoliy DOTSENKO, he was elected chairman of the branch. Muratov regularly participated in the meetings of the UHU’s Coordinating Council in Kyiv. He headed the Moscow organization of the Ukrainian Republican Party (URP) until 1992.

The Moscow branch of the UHU, with its blue-and-yellow Ukrainian flags, took part in actions and demonstrations organized by “Democratic Russia.” The flags were brought by members of the Ukrainian Youth Club, which was affiliated with the UHU. At that time, Ukrainian national symbols appeared at public events in Moscow even more frequently than in Ukraine.

Muratov considered his work in the UHU and the Committee for the Defense of the UGCC from mid-1987 to the end of 1990 to be his most important endeavor. His human rights activities took up all of his time. He often had to meet and see off guests from abroad and from Ukraine. He collected information, processed it, and transmitted it to the West via fax. He wrote articles for Russian and Ukrainian newspapers in the West and for Moscow’s *samizdat*. He met with countless journalists, diplomats, and Sovietologists, both at their request and on the recommendation of his superiors from Ukraine. He received a multitude of visitors. He received office equipment from abroad—computers, printers, fax machines—and forwarded it to Ukraine. On one occasion, KGB agents intercepted and seized a mimeograph machine and a package of leaflets supporting Rukh candidates in an election while they were en route to Ukraine.

In mid-May 1989, Muratov assisted a UGCC delegation (Bishops Filimon Kurchaba and Pavlo VASYLYK, along with several priests and laypeople) that had come to Moscow for a meeting at the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. When they were refused an audience, they declared a hunger strike, demanding the legalization of the UGCC. A. DOTSENKO spread information about this through Western news agencies. Believers in Western Ukraine, together with the Committee for the Defense of the UGCC, decided to support this initiative. Muratov recommended that I. HEL hold the protest on Arbat Street—the only pedestrian street in Moscow at the time, frequently visited by foreigners, where the authorities did not require prior permission for such events. Thus, on May 19, 1989, a relay hunger strike and picketing began on the Arbat, which continued until November 24, 1989. Some of the hunger strikers stayed overnight at Muratov’s home, which could barely withstand the strain.

While in Rome in November 1989, Muratov asked His Beatitude Cardinal Myroslav Ivan Lubachivsky, then the head of the UGCC, for the right to represent the interests of the Church in the USSR. Muratov initiated lawsuits in several district courts in Moscow to defend the honor, dignity, and reputation of the UGCC against the Moscow Patriarchate, TASS, the newspapers *Sovetskaya Rossiya* and *Pravda*, and Central Television, as they had accused UGCC priests of being descendants of Banderite bandits who were murdering Orthodox priests.

After a demonstration of more than 200,000 people in Lviv on November 26, 1989, in support of the UGCC, the authorities were forced to legalize it, allowing the registration of its communities to begin on November 28.

All the events in which Muratov participated, as well as the information he received by phone and in person, were published in the Russian- and Ukrainian-language press in the West and broadcast on Radio Liberty.

On one occasion, after his apartment was searched, he was taken to a local police station where an attempt was made to arrest him for 15 days on an administrative charge. He received phone threats to be “cut into pieces in Kharkiv” and was advised to “think about his children.”

After the collapse of the USSR and Ukraine's achievement of real independence, Muratov’s ties with Ukraine effectively ceased.

On March 22, 2008, Muratov met in Kolomyia with Mykola Simkaylo, the UGCC Bishop of Kolomyia-Chernivtsi. On March 24, 2008, he delivered a presentation at a scholarly seminar at the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv on the topic: “The Committee for the Defense of the Ukrainian Catholic Church in the Struggle for its Legalization in the late 1980s.”

From 1992 to 2008, he worked in various commercial structures with a wide range of responsibilities, from a loader to a representative in court arbitration. He has been retired since 2010. Since 2008, he has been trying to return to the medical profession at the Research Institute of Human Morphology of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences.

He lives in Moscow. His wife, Liliya, a nurse, assisted her husband in his activities from 1987 to 1990. They have two daughters: Hanna (b. 1982), an economist, and Tetyana (b. 1986), a lawyer.

Bibliography:

1.

“The Current State of the Ukrainian Catholic Church (Speech at the Soviet Peace Committee, Moscow, May 19, 1988).” *Khrystyanskyi holos. Zbirnyk pamiatok samvydavu Komitetu Zakhystu Ukrainskoi Katolytskoi Tserkvy* [Christian Voice: A Collection of Samizdat Documents from the Committee for the Defense of the Ukrainian Catholic Church]. Reprint editors: Vasyl Horyn, Mykola Dubas, Halyna Teodorovych. Lviv: Ukrainian Catholic University Press, 2009, pp. 377–381.

“Ukrainskaya Katolicheskaya Tserkov: mezhdu militsiyey i pravoslaviyem” [The Ukrainian Catholic Church: Between the Militsiya and Orthodoxy]. *Russkaya Mysl*, August 26, 1988.

“A Typical Interview with the Editor-in-Chief of an Independent Journal in the USSR; A Human Rights Activist's Explanatory Dictionary.” *The Ukrainian Herald*, 1988, nos. 11–12, pp. 297–299.

“The Decay of a Leader.” *Derzhavnist*, 1991, no. 2, pp. 43–45.

“We Must Do Our Own Work.” *Derzhavnist*, 1992, no. 1 (4), pp. 72–74.

“The Blood-Stained Coal of Donbas.” *Derzhavnist*, 1993, no. 2, pp. 31–33.

“On the Path to an Independent Ukraine: A Look into the Past from Moscow.” https://museum.khpg.org/1301161102

“Vospominaniya pravozashchitnika. Iyun-iyul 2007 g.” [Memoirs of a Human Rights Activist. June-July 2007]. https://museum.khpg.org/1301852597

2.

“Bishop Mykola Simkaylo Met with Mykola Muratov, a Member of the Committee for the Defense of the UGCC.” http://kolomyya.org/se/sites/ep/6954/

“Well-known Russian Dissident Mykola Muratov Visited UCU.” http://ucu.edu.ua/news/1394/ March 24, 2008.

Keryk, Oksana. “Mykola Muratov: In Russia, the Church is Turning into a Museum.” ZAXID.NET, April 3, 2008.

“In Lviv, Russian Dissident Mykola Muratov Spoke About the 'Persecution' of 'Banderite-Bandits.'” http://dailylviv.com/news/15737 April 25, 2008.

Lukianenko, Levko. *To the History of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union*. Kyiv: Feniks, 2010, pp. 20–21, 41, 143, 290–291.

*The Ukrainian Helsinki Union (1988–1990) in Photographs and Documents*. Concept and compilation by Oleksandr Tkachuk. Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2009, 224 pp. (Muratov: p. 46).