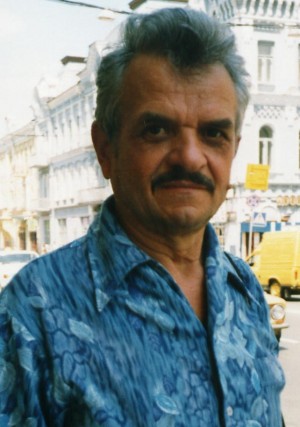

(b. 4 February 1937, village of Stepanivka, Mensky Raion, Chernihiv Oblast)

One of the earliest Sixtiers. Journalist, writer.

Hayoviy’s father was of Cossack descent and had served in the Black Sea Fleet. He was the last in the village to join the kolkhoz. He had the imprudence to remark skeptically at a pre-election meeting: “Why should I have to vote for someone I don’t know at all? I’ve never herded calves with him.” He was arrested in 1938 and perished in captivity. He was rehabilitated 52 years later. His mother, Maria Hayova (née Maniako), struggled with three children and lived to receive a pension of 12 rubles (her average monthly earnings at the kolkhoz were 3 rubles and 40 kopecks); she died in 1967.

In 1955, the son of an “enemy of the people” was admitted to the journalism department of Kyiv University after writing an essay in the style of a humorous sketch, which impressed Dean Matviy Shestopal.

Understandably, he held critical views of the authorities. The 1956 occupation of Hungary spurred the first wave of the Sixtiers: a slightly older student, Borys MARIAN, was expelled from the university in 1956 and imprisoned in January 1957 for 5 years for speaking at a meeting with a minimum program: to remove the privileged caste of communists from power, to allow for the development of trade union and youth movements, etc. B. MARIAN had an influence on the student environment.

In 1957, after his second year, Hayoviy went to Makiivka for a journalistic internship. At the request of the editor of the newspaper Makeyevsky Rabochy (Makiivka Worker) to brand the “anti-Party group of Malenkov-Kaganovich-Molotov and Shepilov, who had joined them,” he said that to him, they were all the same. And although he “arranged for an article” from the secretary of the pipe factory’s party organization, a “signal” was sent to the Central Committee that Kyiv University was poorly educating its students. Hayoviy was said to have praised Trotsky and covered for the anti-Party members: “the anti-Party group of Kaganovich-Molotov, Shepilov who had joined them, and the tag-along Hayoviy.” It was recorded that Hayoviy had spoken critically of Belinsky and Marx, written mocking epigrams about lecturers of Marxism-Leninism, and, to his misfortune, kept a diary.

Meanwhile, he was living on the verge of starvation, sleeping wherever he could. He began demanding a place in the dormitory, but in response, he was required to submit an explanatory note. He wrote the truth—and it effectively became a self-denunciation. That same day, he was expelled by order of the rector “for failure to fulfill the academic program,” even though he didn't have a single “C” grade. He went to see the rector. Academician Shvets flew into a rage: “We used to crack the skulls of people like you! What, are you against the Central Committee? Get out of here!” Hayoviy retorted: “Wait, maybe I'm in the wrong place? Did I wander into a local policeman’s office? Are you quite sure you’re Academician Shvets?” — “Out! And don’t let me see you again!”

He went to Makiivka, where he discovered that the denunciation had been written by the third secretary of the city party committee, Zaporozhets. Dean Slobodyaniuk advised him to earn a good character reference and gave him hope of being reinstated at the university. He worked for a month as a correspondent for the newspaper Komsomolets Donbassa (Donbas Komsomol Member), brought back a good reference, but the “university community” did not agree to his reinstatement.

He tried to transfer to Lviv University. He got a job as a “secretary-typist” in the only vacant position at the newspaper Budivnyk Chervonohrada (Builder of Chervonohrad) (all other positions were held by people who couldn't write). He produced the newspaper almost single-handedly. In 1958, he was reinstated as a third-year student at Kyiv State University. He edited the dormitory wall newspaper ZHLUKTO (a Ukrainian acronym for “Journalistic Legal Universal Cossack Creative Organ”), which Dean Volodymyr Ruban called a “gangster newspaper” and ordered its publication to cease. The next day, another wall newspaper with a similar orientation, Parsuna, appeared in its place.

He graduated from the university in 1961 and worked in Luhansk for the youth newspaper Molodohvardiets (later Moloda Hvardia).

Before that, together with his friends Ivan PASHKOV and Mykola Maksymenko, he arranged a tour for themselves through the cities of Ukraine and Russia, during which Hayoviy kept travel notes where he also recorded jokes about N. Khrushchev. The KGB interpreted these travels as the creation of an “anti-Soviet organization.” An informer, Hryhoriy Hubin, was placed as Hayoviy’s roommate in the dormitory; he read the diary entries and reported them to the KGB.

On March 20, 1962, Hayoviy was summoned to the editor’s office, where two men in civilian clothes put him in a car—he was released five years and three hours later, on March 20, 1967, at Potma station in Mordovia. Hayoviy’s classmate Mykola Prokopenko was forced to write a statement about his disagreement with Hayoviy’s views, which became evidence of the latter's “anti-Soviet views.” Since the investigation could not incriminate him for any specific actions aimed at “undermining and weakening the Soviet state and social order,” and people were supposedly not tried for their views, Hayoviy stubbornly refused to plead guilty. Therefore, he was deemed “malicious,” and on June 20, 1962, the Luhansk Oblast Court sentenced him under Articles 62 and 64, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR to 5 years of imprisonment in strict-regime camps. Ivan Pashkov received a 3-year sentence, and Mykola Maksymenko received 2 years. Hayoviy refused a lawyer, and the trial was closed.

He served his sentence in camp No. 7 (Sosnovka), then at Potma station in camp No. 11 of “Dubravlag” in Mordovia. These were the relatively liberal times of the GULAG: Hayoviy was sent to the punishment cell only once. Like all prisoners, he worked various jobs at the camp’s woodworking plant. Food cost 11–14 rubles a month, but Hayoviy was hardened by his previous life.

Sixty percent of the camp’s population were Ukrainians—insurgents (including Mykhailo SOROKA, Danylo SHUMUK, Hryhoriy Pryshliak, Vasyl PIRUS, Ivan Kochkodan, Yevhen Horoshko, Dmytro Zbanatsky, Volodymyr Hlyva, and the famous physician Vasyl Karkhut), wartime collaborators, and anti-Soviet individuals, including members of Levko LUKYANENKO’s Ukrainian Workers' and Peasants' Union and Bohdan HERMANIUK’s United Party for the Liberation of Ukraine, as well as well-known literary figures Sviatoslav KARAVANSKY, Rostyslav DOTSENKO, Oleksa TYKHY, and Yuriy LYTVYN. There were also groups of Lithuanians, Estonians, Latvians, and Jews.

The camp had its own illegal cultural life: they observed religious and national holidays, and a literary circle was active. Hayoviy wrote poems, including satirical ones, on scraps of paper. From there, he smuggled out a novella written “from-under-the-coat” titled Zirvani kvity (Plucked Flowers), which was published in 1997 in the journal Kyiv, issues 3–4.

After his release, he was unable to work as a journalist for almost 20 years. He was also denied any engineering or technical positions, while manual labor jobs rejected him, citing his higher education. He faced the threat of being expelled from Kyiv on charges of “parasitism.” He worked as a seasonal laborer, a loader, and a stoker. He turned KGB agent Anatoly Litvin’s attempts to recruit him into a proposal to write a book together.

During the eras of “glasnost” and “perestroika,” he began to publish poems and journalistic articles in the informal press and later in other publications. While working at the journal Pamiatky Ukrainy (Monuments of Ukraine), he edited L. Lukyanenko’s book Viruiu v Boha i v Ukrainu (I Believe in God and in Ukraine) and wrote the foreword. He also edited his book Na zemli Klenovoho Lystka (On the Land of the Maple Leaf), published in 1998 and 2002. He was a member of the leadership of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons, and since 1999, a member of the National Writers' Union of Ukraine. From 2000 to 2004, he served as the deputy chairman of the Kyiv organization of the NWUU and now heads the creative association of satirists and humorists of this organization.

In addition to numerous, mostly journalistic, publications in the periodical press, the novella Zirvani kvity (Plucked Flowers), and a large selection of poems titled “Mordovski motyvy” (Mordovian Motifs), included in the collection of prison poetry Z oblohy nochi (From the Siege of Night) (Kyiv: Ukr. Pysmennyk, 1993), he published six satirical books: Bolyachka (The Sore Spot) (Kyiv: “Molod,” 1991), Ukrainski psalmy (Ukrainian Psalms) (Kyiv: “Hart,” 1999), Tin Drakona (Shadow of the Dragon) (Kyiv: “Hart,” 2000), Spodvyzhnyky (Companions-in-Arms) (“Hart” – Kyiv – “Kentavr” – Kharkiv), Peresmichnyk na Parnasi (The Mockingbird on Parnassus) (“Demiur,” Kyiv, 2001), and Blida Pohanka, abo Presumptsiia nevynnosty (The Death Cap, or the Presumption of Innocence) (Kyiv: “Yunivers,” 2004).

He has never been a member of any political party.

Bibliography:

І

Interview with H. Hayoviy, 16 June 1999. https://museum.khpg.org/1120845382

Sketches for a political and creative biography (Excerpt) // Hryts Hayoviy. Postament dlia pamiatnyka z okrushyn navkolorodynnoi ta kolezhanskoi khroniky v avtorskii redaktsii (A Pedestal for a Monument from Crumbs of Family and Colleague Chronicles in the Author’s Edition). – Kyiv: Hart, 2007. – pp. 3–20.

ІІ.

Oleksa Musiienko. Oltar skorboty (Altar of Sorrow) // Literaturna Ukraina. – 2000. – 30 November.

Vasyl Tovstenko. Shestydesiatnyk (A Sixtier) / Makeyevsky Rabochy newspaper. – 2001. – 19 January; Hotovyi ity (Ready to Go) // Vechernyaya Makeyevka newspaper, 21 November 2002.

Arkadiy Sydoruk. Vilnyi u nevilnomu sviti (Free in an Unfree World) // Narodna gazeta, No. 4 (531). – 2002.

Oleksiy Nezhyvyi. Hryhoriy Hayoviy na Luhanshchyni: lehendy ta realii (Hryhoriy Hayoviy in the Luhansk Region: Legends and Realities) // Bakhmutsky shliakh, No. 3-4, 2002. – p. 156; Piat lit za vidmovu kryvyty dusheiu (Five Years for Refusing to Betray One’s Soul) // Ukrainska gazeta, No. 44 (280). – 2003. – 27 November; Zdorov buv, Haidamako! (Greetings, Haidamaka!) // Zona, issue 18. – 2004. – p. 162.

Yuliy Shelest. Zakhaliavna pered- i pisliaistoriia shistdesiatykh (A Hidden Pre- and Post-History of the Sixties) // Lit. Ukraina, 2002. – 10 October 2002.

Yarema Tkachuk. Burevii (Stormwinds). – Lviv: “Spolom” Publishing House. – 2004. – p. 129.

Mizhnarodnyi biohrafichnyi slovnyk dysydentiv krain Tsentralnoi ta Skhidnoi Yevropy y kolyshnoho SRSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava liudyny,” 2006. – pp. 119–122. https://museum.khpg.org/1116603554

Rukh oporu v Ukraini: 1960 – 1990. Entsyklopedychnyi dovidnyk (The Resistance Movement in Ukraine: 1960 – 1990. An Encyclopedic Guide) / Foreword by Osyp Zinkevych, Oles Obertas. – Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2010. – pp. 127–128; 2nd ed.: 2012, – pp. 142–143.

Vasyl Ovsienko, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. 12 March 2004. With corrections by H. Hayoviy in May 2005. Last read on 4 August 2016.