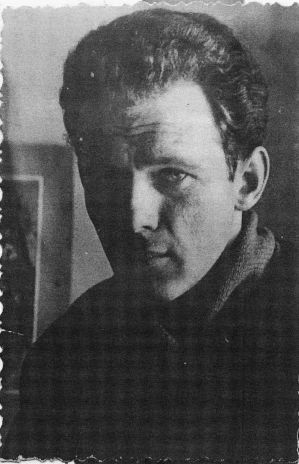

Levko HOROKHIVSKY

COMPLAINT

To the Prosecutors of the USSR and the Ukrainian SSR

In writing this complaint, I, a victim of a shameful judicial process, wish to ascertain whether I must truly see in the people who conducted this trial and investigation the face of a country with the most just system in the world. In people who so savagely mocked my national dignity, the dignity of a human being?

I stand accused of making freethinking statements, which the KGB authorities have twisted into anti-Soviet and nationalist agitation and propaganda aimed at undermining Soviet power. Yet, from my so-called “criminal activity,” no one has suffered moral or material damages—no “victims” have been identified—and yet I have been punished.

Most of the incriminating facts are taken from natural, everyday situations, where it is hardly fitting to attribute special motives to the defendants’ behavior. So, can such “activity” be considered a political crime in a civilized country with a rational social order? Will anyone pay attention to the exclamations of a cheerful company or the statements of individuals in an agitated state? And finally, is it just to deem one side in an argument—where there must necessarily be two opponents—criminal and to arrest them? What talk can there be then of freedom of speech when a fundamental point of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is not observed?! (“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers” (Article 19)).

Were these words not recognized by the representatives of the USSR, who signed this Declaration and acknowledged it as “…an international act, proclaimed by the UN General Assembly on December 10, 1948, as a task toward which all peoples and all nations should strive” (“Political Dictionary,” UkrSSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House, Kyiv, 1971, p. 154)?..

I grew up and was educated under Soviet rule and, naturally, I could not have and did not have any conviction other than one based on a materialist, Marxist ideology. Other ideologies were essentially unknown to me, and I could not have spoken against Soviet reality from their standpoint. After all, to be an agitator or a propagandist, one must be deeply familiar with the ideas that need to be conveyed to others. And finally, what exactly are “agitation” and “propaganda”? The aforementioned “Political Dictionary” states: “Agitation is carried out by disseminating certain ideas and slogans through various means: conversations, oral speeches, the press, radio, cinema, television, theater, visual arts, and political and artistic literature. One of the main forms of political agitation is political information” (p. 13); “Propaganda is the deep and detailed explanation of ideas, teachings, views, and political, scientific, and other knowledge. In comparison with agitation, which is more mass-oriented, propaganda covers a relatively narrow circle of people” (p. 410).

My parents are peasants (my mother, a former farmhand, worked herself to exhaustion in the kolkhoz sugar beet fields, fell ill with cancer, and died; my father is also a peasant; he worked as a hired carpenter—he now barely makes ends meet).

I am Ukrainian (something I never tried to hide, speaking only my native language, and I believe that as a native of the Ukrainian SSR, I should be serving my so-called term of punishment on the territory of my own republic, if it is truly sovereign).

I have a higher technical education; before my arrest, I worked as the head of a project group at the “Ternopiloblkolhospproekt” institute (at work, all project documentation had to be conducted in Russian, despite being intended only for collective farms, i.e., for the villages of the Ternopil oblast, which is inhabited exclusively by a Ukrainian population. This was allegedly because it is economically unprofitable to create some kind of translation center for standard projects issued in Russian. But is it profitable to carry out Russification?).

Recently, I lived in a dormitory in the city of Ternopil, at #1 Lozovetska Street (before that, I had to change my residence 4-5 times due to the lack of housing, which greatly affected my mental state and financial situation).

Sentenced to 4 (four) years of imprisonment… (therefore, I want to compare my sentence with the same term of another political prisoner, for example, one sentenced under the Dutch colonial regime).

From my school days, I knew of this regime, of Dutch imperialism, as I knew of imperialism in general, as something reactionary and anti-human. Of course, it is painful to resort to such paradoxical comparisons, but the Soviet social system, through the interpretation of the KGB’s actions, appears even more anti-human than that colonial regime. After all, the authorities of the Dutch colonial regime also believed that their rule was humane and only contributed to the development of the Indonesian people (Indonesia for them was a mandate (trust) territory), while simultaneously punishing manifestations of national consciousness in practical actions.

“The National Party of Indonesia is convinced that the most important condition for the reconstruction of the entire social structure of Indonesia is national independence. Therefore, the entire Indonesian people must first and foremost be directed toward achieving national independence” (from the book “Indonesia Accuses,” Sukarno, Moscow, 1961, p. 71). And these words were proclaimed at a trial that sentenced the speaker to… four years of imprisonment. But if Sukarno was sentenced as a genuine political figure who led the National Party of Indonesia and wanted to achieve freedom for his people through revolutionary means, then my four years, in comparison with his term, are an act of despotism and a mockery of the human person.

Because I could not have said anything “more terrible” at some party (as emphasized in the verdict) than that Ukraine also has the right to self-determination (both legally and in fact), and that I, as a patriot of my homeland, am not against this right. “The highest expression of the sovereign rights of the Ukrainian SSR provided for by the Constitution of the USSR, as with all union republics, is the right to freely secede from the USSR. This right is convincing evidence that the unification of the Soviet republics into the USSR is genuinely voluntary” (“History of the Ukrainian SSR,” Vol. II, “Naukova Dumka” Publishing House, Kyiv, 1967, p. 377). Yes, these words are often emphasized when it is necessary to once again prove the justice of Lenin's nationalities policy. But try to express this constitutional right out loud… I do not advise you to do so, for you will end up where I am—behind the barbed wire of Mordovia.

Sentenced to punishment in a so-called corrective labor colony… (I do not intend to speak of my conscientious attitude toward work when I was free (my work records speak eloquently of this), and I have never been a parasite who needs to be re-educated through labor. But that is not the catch. Due to my state of health, I… do not work. So why am I being kept here?).

The punishment regime is strict… (have we, first-time convicts, proven to be so dangerous to society that, bypassing the general and intensified regimes, we were punished with the strict one? Is this a means of educating a political prisoner, or perhaps one of the methods of torture? To such a cunning act, any justificatory answers that Article 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR is only accompanied by a strict regime are banal and absolutely do not satisfy me, for to a seeker of truth, the banal cannot be true.

Where I grew up and who raised me was perfectly well-known to the Ternopil KGB. So why did they terrorize me for six months during the investigation over the document “Internationalism or Russification?”, making it an accusation against me? After all, on appeal, this document was recognized as loyal (I was fully exonerated of the charge of possessing and using it). And then they tried me for slanderous fabrications about Russification, when this very process of Russification is convincingly proven in the document “Internationalism or Russification?” Or perhaps Russification does not exist? Perhaps people voluntarily renounce their native language and switch to another? Then let us look at some figures.

According to the 1970 census data, 3,346,000 Ukrainians live in the Russian Federation. But do they have even one Ukrainian school, let alone anything higher? Is there even one Ukrainian newspaper published on the territory of the RSFSR? No! And the entire Ukrainian population of the RSFSR exceeds the populations of the Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, and other republics! Herein lies our tragedy, and it is almost irreparable…

But in the USA (where over one million Ukrainians live), in Canada (where over 800,000 of them live), in Poland (about 300,000), in Czechoslovakia (over 145,000), and in other countries, there are Ukrainian schools and newspapers and journals are published in the Ukrainian language (“Ukrainian Calendar,” 1969, Warsaw Publishing House, Stepan Demchuk, pp. 113-114, article “Ukrainians in the World”)…

I asked a representative from the Lviv television center, who came with a delegation to the concentration camp, about this, and he answered that Ukrainians themselves do not wish to have schools with their native language of instruction (??). But if their self-awareness is so low (for how else can one explain their reluctance to study in their native schools), then why does the government not care for their proper education? After all, education’s task includes cultivating self-awareness, not just providing a qualification. Providing a qualification is a demand of the times, a feature also inherent in anti-human social systems, for technical progress requires a qualified slave. And am I to understand from the words of the television center employee that Soviet education is also developing in this direction? And “attempts to reduce the whole diversity of languages to a single language would mean the same as reducing all the schools and trends that exist in art to a single trend and a single school. Humanity would be terribly impoverished by this” (from the journal “Tekhnika Molodyozhi,” No. 3, 1971, article “The Space of Thought,” by research associate A. Anisimov, p. 45).

At the trial, when my “criminal activity” became apparent from witness testimonies (because I said that over a million Ukrainians live in Kazakhstan (according to the 1970 census—930,000) and there are no Ukrainian schools), the judge said to the witness: “And did you ask him if there are any Kazakh schools in Ukraine (??).” But there are many Russian ones!

What, then, can be said of the historical-ethnic territories of Ukraine, which include the Rostov oblast, the Kuban (Krasnodar Krai), parts of the Voronezh, Belgorod, and Kursk oblasts of the RSFSR, and the Brest oblast (formerly Beresteishchyna) on the territory of the Byelorussian SSR (see “Introduction to the History of the Russian Language,” N.N. Durnovo, “Nauka” Publishing House, Moscow, 1969), where Ukrainians have lived from time immemorial, yet one never hears of even the most elementary education in their native language there.

Of course, this is how everyone will forget their native language, a fact which can be confirmed by a clear example. In the 1920 census, there were 1,222,140 Ukrainians and 980,290 Russians in the Kuban (Krasnodar Krai); according to the 1926 census, there were 1,412,276 Ukrainians and 1,061,535 Russians; but by the 1959 census, 145,592 Ukrainians and 3,363,711 Russians were registered in Krasnodar Krai (“The Modern Ethnic Composition of the Population of Krasnodar Krai,” A.S. Bezhkovich, Leningrad, 1967). What this is—the figures speak eloquently.

“I was simply dumbfounded when I learned that in such a large Ukrainian city as Odesa, with 900,000 residents, there is only… one Ukrainian school” (from the words of an Odesa resident)—these words underscore the aforementioned conclusion without comment.

And how many Russians live in Ukraine?! According to the 1959 census, there were 7,091,000 of them, and in 1970, there were 9,126,000 (an increase of 22%, if we take the figure of 9,126,000 as 100%), while the number of Ukrainians increased during this time from 32,158,000 to 35,284,000 (an increase of only 9%, if the figure of 35,284,000 is taken as 100%). And whereas in 1959, 12.3% of 100% of Ukrainians considered Russian their native language, by 1970 it was 14.3% (newspaper “Izvestia,” No. 90, 1971). But what kind of Ukrainians are these?! And what does this say (without even questioning the reliability of the census data)?

After these figures, the policy of national equality and the face of international unity, which absorbs national minorities that have not even had time to express themselves, becomes clear. For peoples must come to friendship and brotherhood, to international unity, only through the consciousness of their “I,” through economic, political, and spiritual independence. And at the same time, I wish to add that in drawing such categorical conclusions, which have a direct bearing on socio-political problems, I was guided only by the definition of the words “criticism and self-criticism”: “the exposure of faults and shortcomings with the aim of eliminating them; a method of revealing contradictions in a socialist society. In socialist countries, where there are no hostile classes, criticism and self-criticism are one of the main driving forces of the development of society…” (“Political Dictionary,” Kyiv, 1971, p. 260).

The scope of my complaint does not allow me to cover the issue of Russification more broadly and to prove that even if I had defended at trial, and advocated while free, the phrase “Russification is happening here,” I would have been right. In so doing, I wish to refute the accusation: “he slandered Soviet reality and the nationalities policy of the CPSU…,” because, in my continuous search for truth and justice, I have never armed myself with such filthy arguments as lies and slander for my own philosophical generalizations.

But what is there to say of national dignity, when elementary human dignity in these processes (investigative and judicial) was trampled by the most despicable methods, of which only sadists are capable.

“You fell afoul of an overzealous hand” (referring here to the hand of Ternopil KGB investigator Major G. Bidyovka), Major Ponomarenko, an authorized representative of the Supreme Council of the UkrSSR who had come from the Ternopil KGB, told me while I was in the concentration camp (Facility ZhKh 385-17, Ozyorny settlement, in the Mordovian ASSR). “You should have been summoned to a party meeting and given a good talking-to or, let’s say, gotten off with just one year… They went a little too far… But this can be fixed… Write a petition for a pardon” (??).

Excuse me, but who are they fussing over like this, as if I were cattle at a market? If it is me, then how can I be certain about my future life, when it is in the hands of such authorities and completely dependent on their mood?

“…Your trial was meant to serve as a lesson and a warning to others against similar actions…” Major Ponomarenko continued to confess.

Yes, I had suspected as much… And now I am convinced that our trial was fabricated to traumatize the psyche of independent-minded people, to break any independent thought, and to sow pitiful fear before the unshakeable and all-powerful KGB.

“…They made me, they forced me to write a statement against the defendants”—witness Alla M. Koltsova (Tkachenko) shouted, almost in hysterics, during the trial. And after this, a dead silence fell. The judge, the prosecutor, the lawyers—everyone was silent…

“Why didn’t you buy yourself a book on political economy or a portrait of Lenin, but instead were interested in all sorts of histories, in Kalnyshevskys and Mazepas?”—Prosecutor V. B. Khrashchevsky uttered at the beginning of the investigation, when there was not yet the slightest evidence of my “activity.”

But I, I beg you, had 80 issues of the magazine “Ukraina” at the time of the search, each of which contained five portraits of Lenin.

“…And why did you need to write poems about that drunken local trade union committee that was collecting milk from people? Let them collect it,” the prosecutor continued. “And if you’re such a hero, then confess to everything…,” the representative of the law hurried for some reason, and to this day I still do not know what it is I am supposed to confess to.

“You, ‘friends,’ have lost all sense of proportion. We watched you, we watched, and we couldn’t take it anymore…”—one of the KGB officers admitted in a fit of frankness during the first days of my arrest. But when on the second day (replaying the entire arrest scene in my mind once again in the isolation cell), I asked why they had not summoned and warned us, if they were watching us (since the function of investigative bodies is not only to expose and punish crimes but also to prevent them—to warn), everyone denied the words quoted above (they were making a fool of me).

And here is another example. When Major Bidyovka’s investigation was not going well, when I would answer “I don’t remember,” he would send me to the isolation cell with a stream of well-worn Russian curses… and threaten me with the “full measure,” stopping me again and again at the door with the question: “Are you going to talk normally?”(?).

“Respect for the human dignity of the victim and witness, the suspect and the accused, should be the norm of conduct for investigative and judicial bodies. Rudeness and tactlessness, arrogance and formalism are inadmissible in judicial and investigative activities. Jests and irony, offensive expressions, and premature assessments are also inappropriate,” notes Doctor of Juridical Science I. Perlov.

The atmosphere of extreme nervous tension led me to have five seizures with loss of consciousness during the investigation. Is it not barbaric to interrogate a detainee in such a state of health and to use this condition for one’s own purposes? Or does V. I. Lenin’s definition that “socialism is against violence against nations, that is beyond dispute, but socialism is generally against violence against people…” (Vol. 28, pp. 262-263, 4th ed.) not apply to the KGB?

It is only characteristic of sadism to drive a person to despair and then to extract testimony from them; to rejoice when the victim makes a compromise (slanders himself) for the sake of the promised freedom that was taken from him. Because a person, still enveloped in deceptive illusions about the just and compassionate KGB authorities, believes their assurances (and does not understand that this is precisely one of the main methods of obtaining an irrefutable and convenient, but incredibly insidious, accusation).

And the question arises: can a decent and noble person (such were the Chekists Dzerzhinsky wished to see) take upon his conscience an investigation where a person is treated like livestock, where the concepts of honor and humanity do not exist, but only the thirst for a secure life?..

F. E. Dzerzhinsky constantly fought for the purity of the Extraordinary Commission. He wrote, in particular: “…comrades weak to temptation should not work in the Extraordinary Commission, …he who has fallen into temptation and abuses his power for his own benefit is a criminal ‘three times over’” (from the book “In Defense of the Revolution,” Politvydav of Ukraine, 1971, p. 216).

And if the birth of doubts and the spontaneous protest of an individual against injustice is a crime, then what to call the targeted actions of a group of people who conceal mockery and violence within themselves? Perhaps I am mistaken, but I am persistently haunted by the thought that people with such a utilitarian concept of humanism, callously using the law, could have served tsarism, fascism, and other vicious systems with equal readiness.

And after all this, I am to write a petition for a pardon? Because, you see, they haven't mocked me enough, and now they want to wash all responsibility from themselves in such a cynical fashion. Well, they have partly succeeded, by releasing Mykhailo Dmytrovych Samanchuk at the halfway point of his term, who was part of the same case and received the same sentence as me. But our guilt is the same, isn’t it?! Or did he atone for his “guilt” by enduring the final mockery and dispelling the well-founded anxiety of the KGB officers about their future?!

“Don’t be so proud,” Major Ponomarenko solves this problem simply, trying to convince me that life on the outside is still better than in a concentration camp, although… it’s not so bad in the camp either, after all, things were worse for him after the war. But, Comrade.., forgive me, Citizen Major, I do not understand why you use such tired arguments; the war ended long ago, and that was a forced phenomenon—things were bad for everyone, and for some even worse than for you, Citizen Major. And you have not taken into account that I am sick—gravely ill, with advanced pulmonary tuberculosis, which, on such a meager diet as in the concentration camp, could lead to catastrophic consequences. And I also suffer, Citizen Major, from an incurable disease, epilepsy, which, with its frequent seizures and loss of consciousness (which have become much more frequent after the nervous shocks of the investigation), brings me more suffering and torment than the imprisonment itself (and all this without even the most basic medical treatment!).

Is this form of punishment as well (this, Citizen Major, is torture!) provided for by Article 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR? Can it be that in the peaceful 20th century, and in a country that daily emphasizes its humanism, crimes are being repeated that, in my opinion, are in principle no different from the crimes at Buchenwald?

Having come to the firm conclusion of the absolute fabrication and illegality of our trial, and making not the slightest compromise with my conscience, I express a resolute protest against this crying injustice and demand my immediate release from the shackles of imprisonment and full compensation (both moral and material) for the years wasted in vain!

December 10, 1971 L. Horokhivsky

Mordovian ASSR, Potma station, Lesnoye settlement, Facility ZhKh 385-19-5.