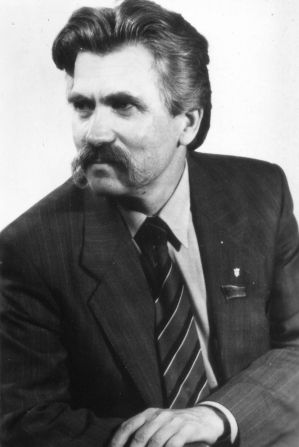

Levko LUKIANENKO

ON THE HISTORY OF THE UKRAINIAN HUMAN RIGHTS MOVEMENT

A people’s history is a continuous thread. So, too, is the Ukrainian yearning for national freedom.

From the 1940s until 1956, an armed national liberation struggle was waged. Since the mid-1950s, the struggle has been carried on by peaceful means. The transition from armed struggle to peaceful methods lasted approximately ten years. The beginning of this transition was vividly demonstrated by a group of lawyers who, in 1958 in the Lviv region, created an organization called the Ukrainian Workers’ and Peasants’ Union (URSS). The organization was intended to become a party, but before its second congress in 1961, it was suppressed and its members arrested; its leader was sentenced to death, and after his sentence was commuted to 15 years of imprisonment, he served the entire term in prisons and concentration camps.

For the first time in the post-war period, the URSS drafted a detailed 22-page program and clearly stressed that it was the heir to the idea of struggling for Ukraine’s independence, while just as clearly emphasizing its lack of organizational continuity with the preceding armed struggle. Thus, the first distinctive feature of the URSS was its clear formulation of independence as its goal; the second was its use of peaceful means to achieve this goal; and the third was its use of law (international and domestic) as a tool in the fight for independence. Regarding the methods for achieving Ukraine’s independence, the program stated: “The methods for achieving our goal are peaceful and constitutional.”

This party of intellectuals was unable to immediately reorient Ukraine’s patriotic forces toward peaceful methods, and so Halychyna [Galicia] continued to give rise to underground organizations with the old, armed orientation.

In 1958, the group of Bohdan Hermaniuk was tried in Ivano-Frankivsk.

In 1960, the underground organization of Yaroslav Hasiuk, known as “Obiednannia” (“Unity”), was put on trial. In 1962, the Khodoriv group (in the Lviv region) of Fedir Protsiv, who was executed, was tried. In the same year, 1962, the 20-member Lviv Ukrainian National Committee (UNC) was tried; Koval, Hrytsyna, Hurny, and Hnot were sentenced to death, and the first two were executed.

Also in 1961, the Ternopil group of Bohdan Hohus was tried, and he was sentenced to death, which was commuted to 15 years of imprisonment. These were the largest underground organizations of 1953–62. They consisted of both young people and participants of the past armed struggle. Not all of them possessed weapons, but all intended to use them. They were the students and heirs of previous methods of struggle, thinking within the framework of old concepts and pondering how to improve old methods. Western Ukraine continued to foster the old spirit of armed struggle for freedom, but gradually, from the beginning of the 1960s, the idea of independence began to stir in Eastern Ukraine as well, and the percentage of people condemned by the colonizers for “national agitation and propaganda” grew ever larger. In the East, the idea of defending Ukraine manifested itself in patriotic enlightenment, which, through self-published (samvydav) poems, articles, and literary and artistic evenings, sought to protect the Ukrainian language, literature, and culture.

The greatest inspirer of the patriotic youth, who would later be called the “Sixtiers” (shistdesiatnyky), was our glorious Borys Antonenko-Davydovych, and their greatest spokesman was the poet Vasyl Symonenko. And there would have been no Sixtiers without the three Ivans: Ivan Svitlychny, Ivan Dziuba, and Ivan Drach, and Yevhen Sverstiuk. Different fates awaited them in the future, but in the first half of the 1960s, they did a great deal to nurture a large cohort of patriotic intelligentsia who rose up against the onslaught of Russification to defend the nation's existence and later filled the concentration camps with young Ukrainians.

The Sixtiers did not sharpen their program to the demand for an independent Ukraine, as the URSS had done. They limited themselves to the demands of national and cultural enlightenment, but since these demands seemed a crime to Russian imperialism and its Ukrainian lackeys, the most active part of the Sixtiers was arrested in August 1965 (although, it is true, the most famous—I. Svitlychny, I. Dziuba, and Ye. Sverstiuk—were left alone by the Chekists, only to be dealt with separately a few years later).

In the history of our people’s underground struggle for liberation, the Sixtiers initiated two new stages.

The first is that from 1965, the patriotic movement began a hereditary continuity. Before the 1960s, many groups had been arrested. Each time, the Chekists tore the group out by its roots, deported them from Ukraine, and subjected their relatives and close ones to intense surveillance by informants, thus preventing any seeds of continued struggle from sprouting in the group’s area of activity. Since all the active people were arrested, the experience they had gained before their arrest remained with them, and they took it with them to Siberia or the Mordovian concentration camps. Any new group that took up the struggle had to master all the subtleties of underground work on its own, each time repeating the mistakes of its equally inexperienced predecessors. The Chekists learned from the ingenuity of individuals in the underground, but the patriots did not learn, because they had no opportunity to exchange knowledge and experience. The activities of the underground groups that began to emerge after the defeat of the armed struggle represented a discrete movement, consisting of the activities of separate groups not connected in time or space. Due to the dense saturation of society with Chekist agents, these groups failed at the stage of organization, having barely begun or not yet started any external activities.

The mid-1960s brought a new phenomenon: not all activists were arrested. A part remained at liberty. The Brezhnev government, seeking to soften international outrage over the mass arrests in Ukraine, did not touch the most famous figures. This group continued its patriotic activity by nurturing new defenders of Ukrainian national interests. The opportunity to pass on experience arose. The movement became hereditary. In place of the former discreteness, continuity emerged.

The second historical step taken by the Sixtiers was the beginning of a new stage in the history of concentration camp life.

A new generation of Ukrainian political prisoners was brought to the Mordovian camps in the summer of 1966. There were relatively few of them, but they overturned the old way of life. Before them, selfless patriots in the camps had engaged in self-education, fantasized about the future struggle for Ukraine’s freedom, resisted the brutal arbitrariness of the administration, and, through hard daily labor, awaited the end of their prison terms. For the administration, we were slaves, but in the internal prison life, we had our own scale for valuing a person's worth and a more or less stable system of authority.

In the spirit of old underground conspiracy and partly due to communist spy mania, there was a fear of connections with foreign countries in the camps, and people rarely admitted to having relatives abroad. Mykhailo Horyn, Mykhailo Masiutko, Valentyn Moroz, Ivan Hel, Bohdan Horyn, and other camp Sixtiers challenged the administration: they openly declared their connections with the democratic émigré community and their right to such connections in the future. Secondly, they introduced the camp to Ukrainian samvydav (self-published literature) and began to collect facts about the administration’s brutal treatment of political prisoners, passing this information to the outside world. They brought a new moral position to the concentration camp: not renunciation of contacts with the outside world, but assertion of the right to them; not asking for forgiveness for passing a samvydav poem to another political prisoner, but boldly defending before the administration the groundlessness of its confiscation; not repenting for collecting facts of the administration's brutality, but condemning the brutality itself. This stance of the Sixtiers was a vivid demonstration of the moral superiority of Ukrainian political prisoners over the principles of the administration, over the moral principles of the entire government. This generation brought to the camps a proposal for honest political prisoners to fight for justice by bringing the facts of injustice to light. This was a new phenomenon. From then on, the entire subsequent history of the concentration camps became a contest between two forces: on one side, honest political prisoners trying to transmit true information about the Soviet camp reality to the outside world, and on the other, the administration trying to prevent such information from leaving the camp's confines. Again, the emergence of this new, useful work in the camps led to a shake-up of the established hierarchy, lowering some and elevating others in their place.

In 1967, the Lviv Regional Court sentenced an underground organization called the “Ukrainian National Front” (UNF). The first defendant in the case, Dmytro Kvetsko, was sentenced to 20 years of captivity: 15 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile. The organization’s inspirer, Zenoviy Krasivsky, received 17 years of captivity: 12 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile. Although the organization arose in the second half of the 1960s, it stood on the old positions of underground struggle and did not belong to the Sixtiers.

The Sixtiers were patriotic enlighteners. They moved the defense of Ukraine from Western Ukraine to Kyiv, to Eastern Ukraine, and by lowering their demands to the linguistic and cultural sphere, they expanded the geography of the movement to all of Ukraine. They were not direct successors of the Ukrainian Workers’ and Peasants’ Union, because they did not raise the issue of Ukraine's right to independence; they defended the right of the Ukrainian people to their language and culture. Gradually, the movement expanded. Behind the words of enlightenment, pro-independence sentiments became increasingly palpable. The colonizers could not stand it, and in 1972 they arrested I. Svitlychny, I. Dziuba, Ye. Sverstiuk, V. Stus, and a large number of other active patriots.

Independently of the samvydav-based enlightenment movement, separate independent groups emerged and were arrested at this time: the group of Dmytro Hrynkiv from Kolomyia, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, and the group of Stepan Sapeliak (Volodymyr Marmus! Sapeliak was the last to be admitted to it. —V.O.) from Chortkiv (from the village of Rosokhach, Chortkiv district), Ternopil Oblast.

In captivity, the executioners crippled Svitlychny and broke Dziuba, but they hardened Chornovil, Stus, Sverstiuk, and many other glorious sons of Ukraine. In place of Krasivsky and Kvetsko’s underground journal “Volia i Batkivshchyna” (“Freedom and Fatherland”) and as a supplement to the reorganized stream of Ukrainian patriotic samvydav, the group behind the “Ukrainian Herald” appeared.

Brezhnev’s imperialist theory of the withering away of non-Russian nations and the formation of a “single” Soviet people, along with a fierce anti-Ukrainian practice, could not but provoke resistance among the people, and in November 1976, the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords was established in Kyiv, continuing the human rights tradition of the Ukrainian Workers’ and Peasants’ Union.

The Helsinki Group based its activities on the Final Act of the Helsinki Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE).

The Brezhnev government, in initiating “peaceloving” diplomacy with the West, had no intention of turning the humanitarian part of the Final Act into real obligations. Its European goal was the legal consolidation of the USSR's armed conquests during World War II, not the humanization of the USSR. Like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Final Act of the Helsinki Conference was meant to remain a paper fiction, serving foreign policy propaganda. In creating the Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords, we understood the illusory nature of the rights and freedoms proclaimed by the Helsinki Act in the conditions of the USSR, but we also understood the great potential power embedded in this international legal document, considering the struggle of the democratic West against the totalitarian, despotic USSR. Thus, relying on the Final Act placed the struggle for Ukrainian national interests on an international legal basis and brought them into the context of the all-European democratic process.

The founders of the Group were the writer Oles Berdnyk, General Petro Grigorenko (died in the USA), lawyer Ivan Kandyba, lawyer Levko Lukianenko, engineer Myroslav Marynovych, expelled student Mykola Matusevych, teacher Oksana Meshko (died January 2, 1991), poet and writer Mykola Rudenko, biologist Nina Strokata, and teacher Oleksa Tykhyi (died in a camp). The group was headed by Mykola Rudenko.

The Group, without raising the issue of the Ukrainian SSR's secession from the USSR as the URSS had done, continued and developed the idea of defending the rights of Ukrainians and Ukrainian national rights. The Group announced its emergence with a Declaration and Memorandum No. 1, in which it sharply condemned the genocide of the Ukrainian people in 1933 and 1947 and the linguicide in the following decades.

The fierce persecution in the first months of the Group's existence, and from February 1977 onward the gradual arrests, forced the Group’s members to focus their main efforts on the defense of individual citizens, primarily former political prisoners and the families of political prisoners. This led to the fact that of all the documents produced by the Group in its first year, 70% concerned the defense of human rights, and only 30%—the defense of national rights.

Of course, the struggle of Ukrainians for their national survival would have continued regardless of the Helsinki Accords or any other international legal document or internal Soviet law, because a nation's right to an independent life arises from its natural right, not from imperial laws or international treaties. However, since such laws and international legal norms exist, they should not be ignored. And the Helsinki Group made the Final Act its cornerstone. This was in keeping with the spirit of the times, and so the human rights line became the dominant feature of Ukrainian national liberation thought, attracting sincere Ukrainians from various parts of Ukraine and different social strata. From the creation of the Group until 1985, 41 people joined (41.—Ed.), and 36 were convicted (27.—Ed.). Of these, Oleksa Tykhyi, Yurko Lytvyn, Valeriy Marchenko, and Vasyl Stus died in prison, and only one, Oles Berdnyk, betrayed the cause.

Finding themselves in various concentration camps and in exile, the Group's members courageously defended the human right to freedom of thought and speech and Ukraine's right to independence. They fought against the despotic regime by all possible means, including continuing to inform the world about the soul-destroying conditions of imprisonment and the Ukrainian people's aspiration for independence. For instance, in 1979, they managed to pass a statement from a Mordovian prison to the UN Secretary-General with a petition to register Ukraine at the UN as a colony. The document was signed by 18 people. For this document, which uncompromisingly exposed the colonialist character of Moscow’s rule in Ukraine, the Chekists took cruel revenge. The deaths of Andriy Turyk, Oleksa Tykhyi, Yuriy Lytvyn, and Vasyl Stus were hastened by this document.

The KGB hindered perestroika and continued the old order in the political zones. In April 1985, a plenum of the CPSU Central Committee initiated a policy of democratization, but five months later, in September, the administration of the Kuchino political prison murdered the poet Vasyl Stus. The year 1986 was one of the same harsh regime as the preceding years. Only from 1987 did some easing begin. The authorities continued to call political prisoners criminals, but under the pressure of world democratic forces, they began to release them from 1987 onward. First, the weaker ones, who agreed to write a statement renouncing further political activity, and then gradually others, stretching the releases out until December 1988.

Having gained freedom, Ukrainian political prisoners resumed the activities of the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords.

In the first months of 1988, it was still uncertain how the authorities would react to the resumption of the Group's activities, so the initial core was composed of people tested by prison and concentration camps. The Group renamed itself the Ukrainian Helsinki Union (UHS). Soon, a good number of people who, although they had not previously been imprisoned, were ready for it, joined the Union. The intellectual potential of the Union was strengthened. The nature of perestroika gave hope for further democratization of Soviet society, and, consequently, for an expansion of the scale of the UHS's activities. Therefore, the Union's leadership developed a program titled the “Declaration of Principles.” The Union remained a human rights organization, but the new conditions made it possible to place the main emphasis on defending not individual rights, but Ukrainian national rights.

As democracy expanded, the possibilities for political activity increased, and the UHS evolved from a human rights organization into an increasingly political one.

Protecting the rights of workers from unlawful dismissals and other violations of individual rights was a constant concern for the UHS, but such protection was an attempt to achieve a just resolution within a generally unjust system. The UHS saw its task in dismantling the unjust system and building a new society in which political rights would be guaranteed by a democracy with a multi-party political system, and labor rights by freedom of economic activity. Thus, from a human rights organization, we gradually transformed into a political organization. Where is the boundary? Where does human rights work end and a political organization begin? Obviously, when it comes to the correct application of an existing law, we can speak of human rights work; when it comes to repealing one law and introducing another, we can speak of political activity.

When the UHS demands the reinstatement of a person who was unjustly fired, it acts as a human rights organization; when it demands the repeal of Article 6 of the USSR Constitution, it acts as a political organization.

The past one and a half years of activity have shown that the UHS's attempts to protect the rights of workers within the existing system yield almost nothing.

The party-bureaucratic and economic-administrative apparatus retreats in individual cases, but as long as power belongs to it and not to the bodies of popular representation—the Soviets of People's Deputies—the communist exploitative system remains in effect, and the worker will be disenfranchised.

The transition from a human rights struggle to a political struggle for the transfer of power to the Soviets is an urgent need of the current political moment. The UHS has made a great contribution to the struggle for the expansion of democracy and glasnost in recent years, but now it would prove not to be up to the historical tasks if it did not take into account the new alignment of socially active forces in modern Ukraine and move to a higher level, reformulating its programmatic goals and its statutory principles accordingly. Human rights activity, it seems, should become one of the many links in the activities of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, reorganized into a party.

April 1990

URP-Inform. Press bulletin. Issue 42 (182), October 18, 1994. P. 7–10.

More than four and a half years have passed since this article was written. In the meantime, dozens of political parties and public organizations have emerged in Ukraine. And almost every one of them proclaims in its program documents loyalty to the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Final Act of the Helsinki Conference. This is not just a tribute to the times. History has proven that the values that guided Ukrainian human rights defenders 18 years ago are enduring, universal human values. They are now being legally established on our long-suffering land, testifying that the Ukrainian people are entering the world community as a civilized people, equal to others.

Thus, the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords was formed on November 9, 1976, and existed until July 7, 1988, when it was reformed into the Ukrainian Helsinki Union. The Group was founded by 10 people. But the circle of people who collected information, prepared materials, and made them public was quite broad. One cannot fail to mention the indispensable secretary of the Group, Raisa Rudenko—the wife of Mykola Rudenko, who was imprisoned for this activity on April 15, 1981, for 5 years in strict-regime camps; or Vira Lisova from Kyiv, wife of Vasyl Lisovyi; or the late Olena Antoniv, wife of Zenoviy Krasivsky, from Lviv—for a long time they were the administrators of the Fund for Aid to Political Prisoners; Hanna Mykhailenko from Odesa; Kyivans Yevhen Obertas and Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska; Olha Orlova from Zhytomyr—sister of Serhiy Babych; Stefania Petrash from Dolyna—wife of Petro and mother of Vasyl Sichkiv—and many others... When their husbands and sons went behind bars, mothers, wives, and sisters took on the heavy burden of human rights defense. They were fired from their jobs, removed from housing queues, their children were barred from universities; in short, they were terrorized, but they stood firm. A new life has called forth new names, but in our swift flight, let us not forget to sometimes look back and gratefully remember the people who in a dark hour defended the dignity of our people before the world, testifying to its indomitable will for independence. Twenty-seven people served a total of more than 170 years of imprisonment, exile, and psychiatric hospitals as members of the Helsinki Group. In total, 39 members of the Group were imprisoned for political reasons; their martyrology counts over 550 years of captivity. The Group included 6 women—all political prisoners. Ten members of the Group have already died, four of them in captivity. Whoever says that freedom came to us easily, let them remember how many lives our people have laid down over many centuries for their main right—the right to live freely.

On April 29, 1990, the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, at its first congress, announced its self-dissolution. The delegates decided to form a political organization on its basis—the Ukrainian Republican Party, which inherited the traditions of human rights defense. And this is logical: we fought for the right to political activity and freedom of association—we were the first to use them as soon as it became possible. True, the authorities delayed for another six months the registration of this first political party in Ukraine.

Other human rights and national-democratic organizations, whose members included former Helsinki Group members, have an equal right to consider themselves heirs of the UHG.

Although the URP inherited the tradition of human rights defense, a “purely” human rights organization, free from party and ideological influences, disappeared in Ukraine. To ensure this continuity was not broken, on the initiative of the distinguished human rights and public activist Oksana Meshko, the Ukrainian Committee “Helsinki-90” was created in June 1990. Vasyl Lisovyi, a philosopher, former political prisoner, and non-partisan, was elected the first chairman of the UCH-90. The Committee focused its attention on defending fundamental individual rights—primarily civil and political. Due to the fact that it is not a mass organization and has no paid staff or funds, the Committee cannot cover the full range of social, economic, and other rights. But it actively intervenes in the process of creating a state based on the rule of law, maintains ties with the European Helsinki movement, tries to influence the legislative and executive authorities in Ukraine, and appeals in necessary cases to the governments of the states participating in the Helsinki process and to the UN. As before, we identify facts of violations of human and national rights by the state, organizations, and individuals in connection with their public and political activity.

The UCH-90 Committee is an associate member of the All-Ukrainian Society of the Repressed.

Vasyl Ovsienko, co-chairman of the Ukrainian Committee “Helsinki-90,” secretary of the URP.

URP-Inform. Press bulletin. Issue 42 (182), October 18, 1994. P. 10.