I have already had the occasion to share my memories of Oleksiy Ivanovych Tykhy (see the collection of materials from the academic conference dedicated to the memory of Oleksa Tykhy, “He Who Did Not Bend in Spirit.” − Druzhkivka, 1994. − pp. 10–17). In the current version of this text, based on my occasional notes that were hidden until recently with relatives in the Brest region, I present some new facts and clarify a number of points previously stated from memory.

There are personalities who, from the first moment you meet them, somehow attract you, evoke sympathy, and a desire to continue meeting and talking, conversations that are remembered for their uncommonness.

As an associate professor at the pedagogical institute (in Sloviansk, Donetsk Oblast) at the time (in 1976), my professional activities required me to interact with a large number of people—full-time and correspondence students, teachers from the district and region (especially during various seminars and courses), and other categories of the population at regional and republic-level conferences and meetings. However, the faces of my interlocutors and the topics of conversation were quickly forgotten. But my meetings with Oleksa Tykhy have remained in my memory, though quite a lot of time has passed since then.

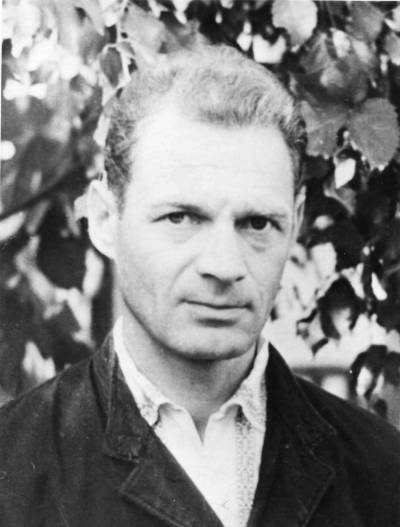

Our first meeting took place in 1976. During that period, I was teaching the Ukrainian language at the Faculty of Primary School Teacher Training at the Sloviansk Pedagogical Institute. This faculty was located in the academic building at 1 Kalinina Street (now the pedagogical faculty is here). I remember it well: the third class period had just ended, and as I was leaving lecture hall No. 7 (on the second floor, near the dean's office), a stranger of an intellectual appearance approached me:

– Are you Vasyl Tykhonovych?

− I am.

Apologizing for bothering me, he introduced himself and addressed me:

− I would like to talk to you, to consult with you. The thing is, I am working on a Russian-Ukrainian dictionary…

– But such dictionaries already exist. What new thing could you discover or create there?

– But the one I am working on does not exist. It is a dictionary of corruptions—words of Russian origin that are used by the local population and do not conform to the norms of the Ukrainian language. The task of the dictionary is to help the reader, first and foremost the teacher, to avoid them.

– Alright. After classes I feel tired, and it’s time for lunch, I’m in a hurry to get home. If you have time, let’s walk together, we can talk on the way, you can tell me about your idea, your work.

At that time, my family lived in a small two-room apartment on the fifth floor in the Artema microdistrict (5 Parkovyi Lane, apt. 12). The road from the institute building to my “home” was quite a long one—about five kilometers.

I liked this man immediately—a pleasant facial expression, his excellent command of the Ukrainian language made a very good impression, which was quite a rarity in the Donetsk region, his manner of speaking was thoughtful, without interrupting his partner, and one could sense a broad erudition and intelligence. A deep, hard-won subtext could be divined behind a simple, even seemingly banal phrase. Lost in conversation, we covered the distance without noticing. At first, we spoke of ordinary things, current news, testing each other—to what extent could we be frank? Gradually we moved on to the painful topics of schooling and Russification, without using politically sharp expressions. We somehow unexpectedly found ourselves in front of my apartment building. Oleksa started to say goodbye, but I persuaded him to come up and have lunch with me.

After that, we didn't meet at the institute—he would come straight to my apartment, and he even stayed the night once or twice.

I will dwell on a few moments that are also important for understanding the socio-political atmosphere of the time. We didn't have critical conversations about official Soviet policy at the apartment. When we did talk about the leaders of the day or the “fateful” decisions of the party, it was in a purely factual way: we knew very well that “the walls have ears.” The conversations took on a different character when we found ourselves in places where we were certain no one could overhear us. Our “posyolok” Artema was being built up, and next to the building where I lived, there were neglected plots of land, remnants of forest plantations. I would walk Oleksa to the bus station, and we would turn off to the side, as if taking a shortcut, and this was an opportunity to be more candid.

However, even in this case, we followed unwritten rules of caution—we avoided specifics unless there was a practical need for them, so that in the event of an unforeseen turn of events, some unexpected incident, we would not lead potential snoops onto an undesirable trail. For example, Oleksa Tykhy spoke of the existence of a resistance movement in various cities, mostly without naming names (except for those known even from the press—Lukianenko, Rudenko, Hryhorenko), and without revealing what specific individuals were engaged in. He spoke of arrests, political prisoners, the struggle against the regime.

As I learned much later, he had quite close contacts with Hryhoriy Hrebeniuk, a candidate of technical sciences who lived in Kramatorsk, not far from Sloviansk, and with Yaroslav Homza, a German teacher in a secondary school (in the village of Ocheretyne near Yasynuvata). I don't recall him ever naming them. It seems it was after Oleksa Tykhy's death in prison that they unexpectedly appeared at my door in the evening, which made me quite suspicious of them. It’s funny to remember now: they stayed late for dinner and conversation, and I had to let them stay the night. Locked in the next room, my wife and I “didn't sleep a wink” all night. It was a time when people were afraid of each other.

For my part, I said nothing about my own “reprehensible” acquaintances, nor about the fact that I had been under investigation. I don’t recall if I told him that I had been fired from my job in Kirovohrad for connections with dissidents and distributing samvydav literature, and only a year later received permission to work in the Russified Donetsk region. We most often talked about the Russification that was rapidly advancing, about the political conditions in which it was important to survive not just for biological existence, but for the sake of the struggle, and what could be done that would be useful for the nation in the conditions of its total destruction. In the end, much of what was said was reflected by Oleksa Tykhy himself in his article “Thoughts on My Native Donets-land,” published only in the years of independence (see Donbas journal, 1991, no. 1).

By the way, about the dictionary. It was a cleverly devised, seemingly innocent means of establishing contact with individuals not well known to Tykhy, and in the case of a positive reaction from the interlocutor, to deepen the acquaintance. In this way, it was possible to identify a circle of people sympathetic to the national idea and gradually involve them in organized work. And once we got to know each other better, we no longer spoke of the dictionary.

During one of our “walks,” Oleksa told me about a female acquaintance of his who was fired from her job for having contact with him. In this connection, we agreed: in case they “call us in,” or “start working on us,” it was not worth denying our acquaintance. What did we talk about? About the dictionary and ordinary, everyday things. In short, we coordinated who among us would “confess” to what.

This conversation turned out to be prophetic—soon I would have to face an investigation. This agreement helped me a great deal during the interrogations at the KGB; it gave me confidence. But more on that a bit later.

One time, Oleksa brought a typewritten, bound book, quite large in volume—a collection of quotations from the “classics of Marxism-Leninism” and other communist leaders about the Ukrainian language, various resolutions of the Communist Party and the Soviet government, interesting materials from the period of “Ukrainization” of the 1920s and early 1930s, and other official documents. He promised to leave it with me for a long time, but the next day he came and took it back—he was urgently leaving for Kyiv: he wanted to take it to the Institute of History for them to give their opinion, perhaps the collection could be published (did he really hope for this?). I was sorry to part with this material, as I hadn't had time to copy anything from it; by that time, I myself had managed to collect something on this topic and compile my own collection, part of which I later had to destroy when the threat of a search arose. It was even surprising and pleasant that another person had been found who had set out on this same path. Oleksa promised to let me supplement my collection from his work, but unfortunately, I did not manage to take advantage of this (the materials I collected and processed were included in the book “The Colors of the Ukrainian Language,” printed in 1997 in a ten-thousand-copy run by the publishing house of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy).

No matter how we tried to hide, the “organs” discovered our contacts. The apartment next to ours had been unoccupied until then. And so, shortly after one of Tykhy's visits, a lanky individual of a rather suspicious (one might say, characteristic) appearance paid us a visit, supposedly for the purpose of getting acquainted, announcing that he had received this apartment. He moved in alone, without a family. A day or two later, late in the evening, he asked to be let through our balcony (our balconies were connected) to his own, because he had forgotten his keys at work. There were several such “forgettings.” The purpose of his visits left no doubt, as something similar had already happened in my life: back in 1959, Yevhen Sverstiuk and I visited Ivan Brovko, an associate professor at Kyiv University, where we talked on literary and historical topics, allowing for “deviations from the party line,” while in the neighboring “unoccupied” room, the “state shepherds” diligently recorded what was said. Our meeting was later classified as a timely uncovered attempt at an anti-state conspiracy. So, it was not difficult to guess whom this “gentleman” was hoping to catch (as I learned later, he was a police major named P. Smolkov). Were the KGBists perhaps hoping to catch the malefactors “red-handed”? By the way, when the Tykhy case was closed, there were no more visits, nor even this “neighbor”—the apartment was given to the family of another police officer, who still lives there to this day.

And so, in March 1977, I had to become one of the subjects of the investigation in the case of Oleksiy Tykhy. Briefly, about some circumstances related to this event. My wife (Lidia Dmytrivna) had visited her parents in the Mykolaiv region for the Women’s Day holiday (March 8). It was decided that she would bring back my notes that were hidden there, to then transfer them to relatives in Kyiv, where we planned to take our school-age son for the spring holidays.

On the evening of March 23—a knock at the door. I open it. A stranger enters: "Are you Horbachuk, Vasiliy Tikhonovich?" − I am. − "You are being summoned to the Committee for State Security. The car is downstairs." I say I’ll get ready, get dressed. He went out. As soon as the door closed behind him, I grabbed the folder with the “seditious” materials and, through gestures, asked my wife—where should I hide it? We darted around the apartment—nowhere! In this feverish moment, a thought flashed: in the bathtub! We put it under the laundry in a basin. In case of an emergency—we'd fill it with water.

I went out. I approach the car waiting by the entrance, the man who had summoned me is at the wheel. I get in silently. When we got onto the road, I asked why so late, since working hours were over? − "We work at any time," he replied. There’s an anxiety in my heart, I guess it will be about Tykhy. What else could it be about?

We drive into the courtyard of the Sloviansk KGB (the gate was open: they were waiting). I enter the indicated room. A man gets up from behind a massive desk, introduces himself: Anatoliy Vasilievich. He offers me a seat. He asks about my job, working conditions, says he had the best opinion of our institute, thought everything was fine there, but now (he hands me a piece of paper) a summons to Donetsk for tomorrow. − "What is the matter?" − he asks. I say that I don't know, I can't even guess.

I return home as dusk is falling. My wife meets me, frightened, questioning. We go out “for a walk,” examining nearby bushes and pits—where can we hide the folder? What if there's a search tomorrow? And how did it happen that, as bad luck would have it, she brought it just in time for this fire? It should have stayed there, in the village, for another few years. I could tear it all up, destroy it. But how can I raise a hand against my own work? If they find it—I’m done for, but if there’s no search, you’ll endlessly regret what was destroyed. Returning from our walk, we spent the night sorting through what could be left and what had to be eliminated. What was left we crumpled up and put in the trash bin.

The night, of course, was anxious. Several times I reread the “Summons” addressed to me (which I still keep): “You are invited to the Directorate of the Committee for State Security at the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR for the Donetsk region—city of Donetsk, 62 Shchorsa Street, to the office of comrade Nagovitsyn on ‘24’ March 1977, at ‘10:00’ hours… Failure of a witness to appear without a valid reason will result in his being brought in by force, with the simultaneous application of other measures…”

At nine in the morning, I had already arrived in Donetsk, found Shchorsa Street, and the building on it. A beautiful sunny morning. I am thinking over possible variants of the “dialogue.” At exactly 10 o'clock I go in, hand my documents to the guard on duty—my passport and the summons. He tells me to wait.

In the lobby, there is some boy (about 18-20 years old), agitated about something, pacing from corner to corner, deep in thought. Two elderly men are sitting on a sofa by the window. I sit down beside them, open a newspaper, and listen to what they are saying. “I've lived a long life, but I’ve never been hauled in for politics before,” says one. The other confirms this as well. It turned out they were both from Kostiantynivka. A little further sits Valentyna Yevhenivna Protasova, head of the Department of Ukrainian Language and Literature at the Regional Institute for the Advanced Training of Teachers. We greeted each other, exchanged some general phrases. She doesn't know why she was summoned. Some fellow noticed this and (in Ukrainian): − "So you two know each other?" She immediately blurted out: "This is a lecturer from the Sloviansk Pedagogical Institute, a candidate of sciences." He quickly took her away. After that, I waited my turn for about an hour and a half. The “comrade” who came for me led me to an office on the second floor (I didn't notice which way Protasova was let out).

A middle-aged man rises from behind the desk, and introduces himself (in Ukrainian):

– Investigator for Especially Important Cases Simchuk. From Kyiv. And this is my colleague (he said either his last name or his first name and patronymic—I don't remember, it was probably Nagovitsyn)... Have a seat.

They began in a seemingly casual and friendly manner: where I work, how long I’ve been in Sloviansk and where I came from (as if they didn't know), why I changed jobs, how my work is going at the new place, and so on. And, finally:

– What do you know about Tykhy? What can you tell us about him here?

Although I had expected such a question, a thought flashed through my mind: how could I buy some time to think, so as not to blurt out something extra in the heat of the moment? How could I create the impression that I supposedly didn't even know this man? How could I play the naive fool? I say:

– He's a famous Ukrainian artist, his painting “The Road to the Collective Farm” was often reproduced in magazines...

At first, they seemed dumbfounded, and then they interrupted my story: that wasn’t the Tykhy they were interested in!

“Oh, the thin one? Some village teacher” (he corrects me: not a teacher, but a firefighter). “Is that so? He didn’t tell me that.” I go on to tell them how he approached me after a lecture at the institute and asked me for a consultation.

“On whose recommendation? Why me specifically?”

“No one’s. He said he went to the dean’s office and asked how he could meet with a linguist to get a consultation. So they pointed him to me, as I was giving a lecture right next door in the adjacent classroom.”

In my testimony, I held onto the dictionary not just like a drowning man clutching a straw, but like a sturdy log, with the hope of floating to safety. I said that I couldn’t refuse a teacher asking for a consultation, that countless teachers come to our department. Furthermore, both the Ministry of Education and the institute’s administration direct us to maintain the closest possible ties with teachers; our work is even evaluated on this basis. What could be wrong with a man compiling a dictionary?

“And do you know what kind of dictionary this is?! It’s a nationalist dictionary! Did you read its foreword?!”

“No, I haven’t read it. Did it have a foreword? He didn’t show it to me” (I feel the blood rush to my face: several pages of the dictionary itself, with that very foreword, are hidden in my house. What will happen if they search the place and find them?!). “But I didn’t agree to collaborate with him anyway. We had a difference of opinion: I didn’t approve of his project.”

They asked what topics we discussed besides the dictionary (the usual ones. How can one remember what one talked about with a random person yesterday, and a lot of time has passed since then?), what I gave him to read, whether I gave him a “quote book” (I heard this word for the first time, but I guessed what it meant and asked them to explain it. They looked at me with distrust but finally informed me that it was a tendentious collection of statements about the Ukrainian language, selected from a nationalist perspective).

“No, I didn’t. Besides, if the collection was like that, would Tykhy have confided in me, a person he barely knew?” They replied indignantly: “We know he slipped this harmful scribbling to many people; he even took it to Kyiv to distribute!” (As I later learned, a copy of this “quote book” was kept well hidden by Yaroslav Homza.)

When the tension subsided a bit, my attention was drawn to a small table against the wall. On it was an old-model typewriter; a rifle (or a hunting shotgun) stood beside it, along with something else.

“This is material evidence of his criminal activities,” Simchuk remarked. “He typed anti-Soviet materials on the typewriter. He created a secret organization, collected weapons to start a rebellion. We want to find out just how involved you were in this.”

The interrogation ended; they gave me the protocol to sign (on every page). I burst out of that KGB building with a sense of relief: there were no serious accusations against me, and most importantly, I hadn’t let anything slip or harmed Oleksa: my testimony remained within the bounds of my “agreement” with him. I unwisely went straight to the editorial office of the magazine “Donbas,” where my article on the Belarusian poet Maksym Bohdanovych was. They told me the article had been positively reviewed and was already prepared for publication (however, it was never published).

The following day (that is, March 25, a Saturday), I was summoned to the Sloviansk State Security Committee. Here, I was met by the same Simchuk and the head of the regional KGB investigation department, Melnikov. Apparently, the Donetsk protocol hadn’t satisfied them in some way, or something had piqued their interest: they decided to conduct an additional, “in-depth” inquiry. Simchuk, after I took the indicated seat, began (in Ukrainian):

“Why are you nervous?”

“I’m not nervous.” And indeed, I didn’t feel nervous.

“What are you talking about, can’t I see that you’re nervous? Are you hiding something from us? You’re not being sincere with us! Why?! Afraid of the consequences?! You mentioned a Tykhy from Kyiv. What do you know about him?”

I wondered if I had accidentally stumbled into a new mess. Or were they just probing, wondering if there was some secret hidden in our relationship? In truth, I only know this artist from reproductions of his paintings. I named a few of them and briefly described them.

Then they started on Storchak: How long have you known him? What do you know about him? Where did you meet him, have you been to his home? And all of this was done in a crude, nitpicking, aggressive manner.

This moment struck me: how did they know about our relationship? They had never pinned him on me before! Could it have come from I. I. Boholov? [Kindrat Markovych Storchak was a Doctor of Philology, a senior researcher at the Scientific Research Institute of Pedagogy at the time I was a graduate student there. It was interesting to talk with him. I’ll never forget one episode: we were walking along Khreshchatyk, and the conversation turned to Ukraine, its sad history and its future. He put his hand on my shoulder: “Vasyl, you will yet live in an independent Ukraine.” “Are you serious? Can’t you see the pace and planning of the ongoing Russification?!” “It’s bad, of course, but at the same time, forces are growing within the depths of the system that will change this situation. I emphasize once again: Ukraine will be independent.” His words, his reasoned confidence, struck me so much that to this day I remember exactly where this conversation took place way back in 1955! We always had a friendly and mutually trusting relationship]. I denied any connection to him in every way possible. I said that his department (Ukrainian literature) was on a completely different floor from ours—language methodology—that our interests and fields of activity were completely different, and besides, there was a large age gap between us.

Then Simchuk left, and the corpulent Melnikov continued the interrogation in Russian. I remember his fleshy face, his portly, well-fed figure. Gesticulating with his massive hands, extremely enraged, he flipped through the sheets of paper on the table before him, where my past and present “transgressions” were gathered, and commented on these “crimes,” emphasizing their gravity, anti-state nature, and malicious character.

When I remarked that I had committed no sins in recent years, he said indignantly: “You said that this recent story with Dobosh is just a pretext to destroy the Ukrainian intelligentsia!” “I not only never said such a thing, it never even crossed my mind!” “Come on! Who’s going to believe you?! It’s been recorded, there are signatures.” [It flashed through my mind: who did I tell?! Who passed it on? Could it be Mykola Skyba? I remembered: walking with him through the park to the institute. Passing by the monument to the unknown soldier, we somehow started talking about Dobosh—a Ukrainian from Belgium who had briefly come to Kyiv on some business. He had supposedly, according to the KGB’s version, begun to establish spy contacts with the Kyiv intelligentsia. I had incautiously blurted out the very phrase the investigator quoted. Skyba, glancing at me, had said: “Could be.” With that, we changed the subject].

Then Melnikov began to dig into a very old story (from back in 1959) involving Ivan Brovko and Yevhen Sverstiuk. He stated with satisfaction that Brovko was ill (supposedly didn’t have long to live) and Sverstiuk was in prison. “They still haven’t disarmed,” he noted emphatically.

Finally, the investigator voiced a completely unexpected sin, one I had never been accused of before: ties with Belarusian nationalists (a memory flashed in my mind: the newspaper *Litaratura i Mastatstva*, which I had subscribed to a few years prior; a discussion in its pages about the catastrophic state of the Belarusian language; I had written a letter to the editors addressed to one of the participants in the discussion, approving of his position, and had quoted lines from Maksym Bohdanovych’s “The Chase”: *«Бийте в серця їх, бийте мечами, не давайте чужинцям буть!..»* Could this “fact” really have been entered into my dossier?).

“We know you well. And your place is there” (he made a distinct gesture). “You are a real dissident! It’s only by chance that you haven’t ended up there. I’m surprised it turned out this way.”

Expressing his extreme surprise and even indignation at how patient and indulgent the punitive organs had been, Melnikov noted that in his more than twenty years of practice in the investigative organs, he could not recall such a person remaining at liberty (he made a gesture of decisive intent to correct such a terrible oversight).

At that point, I felt: this is probably it, the end. I remembered the words of a Kirovohrad KGB agent, Vasyl Chornomorets, said to me in parting (during my last “prophylactic session”): “We’re letting you work, but I advise you—don’t get caught. Over there in Donetsk, they’re such chauvinists that if you get caught, they’ll mix you with crap.” This one will do the mixing, I thought. Gesticulating, he questioned: “How did it happen: in the entire Donetsk oblast, only one nationalist was found, and you cozy up with him?!” I recalled an anecdote: a state security department head sent an operative to some meeting to watch out for anti-Soviets who might “reveal” themselves. After the meeting, the operative brings in a citizen. “Brought in an enemy,” he reported. “How did you spot him so quickly?” “An enemy never sleeps,” he explained. “This guy listened attentively to the entire report while the rest of the hall was dozing.” And so it was here—I wanted to say—how could you not notice a personality in such a drowsy society? Aloud, I said: “It was pure chance that he approached me.”

“Who recommended you to him?”

“I think it was the dean’s office, where he went for help. You’d better ask him about it yourself...”

“Why did he end up with you specifically? There’s a pedagogical institute in nearby Horlivka too.”

I explained that the pedagogical institute of foreign languages in Horlivka doesn't have a specialist in Ukrainian studies.

“How could you not figure out the nationalist bent of the dictionary?! Are Russian words in the Ukrainian language a form of contamination?!”

To somehow convince Melnikov that in principle there couldn’t have been any suspicious conversations or secret dealings between me and Tykhy, I let it slip: “After all, one can always suspect a stranger of being a provocateur!”

“Aha, so that’s what it is!” he bellowed. “He thought they’d set a stool pigeon on him! What would have happened if that suspicion hadn’t crept in? You would have moved toward a closer relationship with him!”

His reaction comforted me, if one can use such a word in the situation described.

No interrogation protocol was kept; he suggested I write an explanation. While I was struggling with the wording, one of their employees started bringing packages and crates of bottles into the office (Wow, what an appetite! I thought). My tormentor, hungry and thirsty, did not detain me much longer.

Returning home, I told my wife a little of what had happened, convincing her that it was just another “prophylactic session.” But I myself waited... I destroyed everything for which the *oprichniki* could “open a case.” To this day, I regret the loss of some of those materials. I was tormented by a feeling of terrible loneliness and defenselessness: who could I turn to, with whom could I share my anxieties, where and with whom could I hide what should not have been lost?

One detail remained a mystery: my wife, Lidiya Dmytrivna, had given Oleksa a copy of her methodological paper, “The Development of Coherent Speech in Primary School Students,” which she had written and which had just been published by the Ministry of Education of the UkrSSR, with a dedication “with best wishes from the author.” And so, strangely, this author’s gift did not figure during the investigation as “material evidence” of criminal ties. Did they not find it, or did Tykhy himself destroy it, sensing the imminent danger?

I was not summoned again in Tykhy’s case—neither for interrogation nor to court. For a long time, in that realm of silence, I did not know what sentence Tykhy had received. One day, by chance, in conversation, one of my colleagues at the institute, Professor Anatoliy Fed, a former party functionary who had suffered for hiding a book by Yulian Movchan published in Toronto, Canada, *Pro shcho varto b znaty* (What One Ought to Know), mentioned his surname.

“Interesting,” I said cautiously, not revealing my acquaintance with this person, “what kind of man is he? Is it the same Tykhy, the artist from Kyiv?”

“What artist?! There was a teacher here in Druzhkivka who was convicted of nationalism.”

A story, retold by someone (was it Anatoliy Fed?), has remained in my memory: Oleksa Tykhy goes to see the head of the district committee, Nosovsky, one day and says: “What is happening here in our country?” “What exactly?” asks the chairman. “There’s wholesale Russification going on...” Tykhy begins his story. “Hold on, I’m busy, just a minute...” He calls in his secretary, tells her to summon someone urgently (it turned out to be the head of the district KGB), and buries himself in his papers. The summoned man soon enters and sits down. Then Nosovsky, looking up from his documents, says, “Alright, tell us what business brings you here.” Tykhy starts to explain... The “guest” listened for a bit, then stood up, slapped Tykhy on the shoulder, and said, “Enough! Let’s go! Everything’s clear.” And so, after that, they opened a case against Tykhy. But you can’t “pin” much on a person for that, so they decided to find some compromising material. They conducted a search and “found” a weapon they had planted on him, a typewriter on which he had supposedly typed leaflets and other anti-Soviet materials, which he then distributed. And that’s how they threw the man in prison. (The conversation in the district committee was in 1957; the episode with the weapon was in 1976.—Ed.)

I recount this story understanding that it may be quite far from the actual facts, which are, moreover, jumbled, but it was the only news that reached me about this remarkable person after his arrest, trial, and exile (Imprisonment.—Ed.). None of my other acquaintances in Sloviansk had heard about the trial, the story with Tykhy, or even his name. How skillfully the “organs” could remove a person from society so that not even a rumor about them remained, as if they had never existed at all! And most importantly—for what? It would seem that this man had done absolutely nothing illegal, even from the point of view of their own, Soviet constitution.

In early March 1979, having gone to the Donetsk Institute for Teacher Improvement on some business, I met V. E. Protasova in the corridor. We greeted each other. She immediately pulled me aside and said in a whisper: “I’ve been wanting to see you. What business did you have there? Was it about… [she hesitated] Tykhy?” She told me that the investigator had questioned her about me as well. With a naive expression on my face, I asked: who is this Tykhy? “He worked as a firefighter,” she replied, “but he told everyone he was a teacher. He was looking for like-minded people. He was collecting quotations and materials about the Ukrainian language.” “What happened to him?” “They put him in prison. There was a regional meeting of party activists where they announced that Tykhy had engaged in hostile activities and was convicted for his crimes.” “I heard,” I say, “that Tykhy supposedly graduated from Moscow University, the philosophy department.” “So he’s not even a linguist?” “No.” “Ah, so he’s a nationalist? He got what he deserved.” For a long time afterward, that final phrase kept spinning in my mind: was the esteemed Valentyna Yehorivna simply a *sancta simplicitas*, a product of propaganda, or was she camouflaging her real thoughts, wary of me (as I was of her)?

For a long time after, any knock on the apartment door filled me with anxiety: had they come for me? One day, during a break, the secretary from the dean’s office approaches me: Zaichenko (the pro-rector for educational and disciplinary work at the Sloviansk Pedagogical Institute, who was filling in for the rector who was away somewhere) wants to see you. I enter his office. He says officially, dryly:

“The Sloviansk State Security Committee is summoning you, you must report tomorrow. Do you have classes?”

“Yes.”

“Tell the dean’s office to find a substitute.”

That night, of course, I couldn’t sleep again: why, for what case? It turned out to be about a case involving our department's associate professor, Polyakov (based on a denunciation against him, as was later suspected, by the assistant, Mykola Skyba). The informer had set me up as a witness to a seditious conversation. I assured Petrov, our institute’s “curator,” that I had heard nothing suspicious.

By the way, some time after the events described related to Tykhy, the pro-rector for academic affairs at the institute, Associate Professor Oleksandr Hryhorovych Zaichenko (he had a wide circle of influential acquaintances), hinted in a conversation with my wife with a single phrase that he had averted a great misfortune from me and our family. He did not want to clarify what it was, when it happened, or how it had come about. He promised he would tell me later. Unfortunately, he died soon after.

At the end of the 20th century, such a frosty, dark night! A polar silence! And a miracle: as if unexpectedly, the prison that had seemed indestructible, long-lasting, and strong, collapsed. The slave, despised, branded, tortured, now stands before us in the image of a hero, a person worthy of honor and emulation, the personification of the best part of the people of Donbas. Donbas will forever be proud of Oleksiy Tykhy, Ivan Dziuba, Vasyl Stus, and the Svitlychny family. And where are their persecutors and tormentors? For now, they have not suffered; they enjoy the benefits granted to them for identifying and removing the righteous from life. Those who let people rot in prisons, who shot them in the back of the head, who supported and strengthened the criminal regime, have large pensions and various privileges. To this day, they and their children burn with hatred for nationally conscious Ukrainians. But there is the judgment of history; it will put everyone in their place: some in the rays of glory, others in the abyss of shame.

This version of the memoir is published for the first time. Prepared for publication by Vasyl Ovsiyenko.