Kharkiv, late 1990s.

It was with great joy that I accepted the offer to write about my friend, Yuli Daniel.

My joy comes from the simple pleasure of writing about him, but even more so from the fact that, in my opinion, he was not given his due either in his life or after his death.

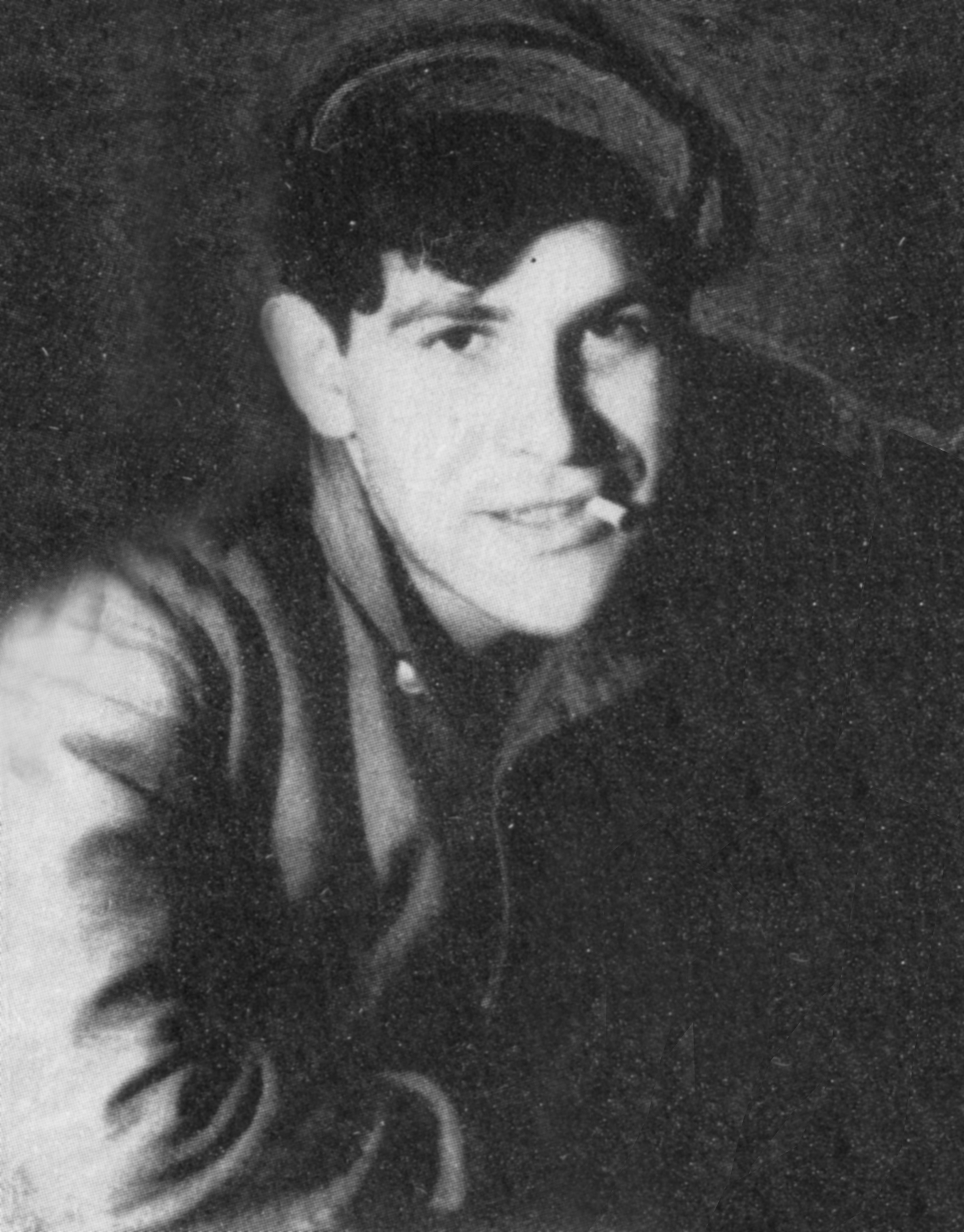

I met Yulik in the fall of 1946, when he enrolled at Kharkiv University. Yulik was my age, but the boys in our generation were being demobilized from the army and were therefore late with their studies, having spent those years at the front. Besides, for some reason, Yulik, a Muscovite, ended up enrolling specifically at Kharkiv University. A year later he transferred to Moscow (to be with his mother), but the friendship that had formed between us lasted a lifetime, as was the case with him and other people. I have already mentioned that we formed a group (from different years of study) that was looked after and supported in every way by Vera Alekseyevna Pychko, who was in charge of our foreign literature department. The guys who joined this group (or, simply put, our circle of friends) were all very bright, each distinguished by some talent. All our boys, except for the two “younger” ones, were war veterans. Yulik had also suffered a serious wound.

Our friendship was, on the surface, somewhat superficial: wits, jokes, mischievous antics—this is what occupied our time, with serious conversations seemingly dissolving into them. For a while, we did some side work in a library, writing bibliographic cards. During those days, we came up with nicknames for each other based on movie titles: Yulik was “The Mistake of Engineer Kochin,” and I was “A Restless Household.” But our deep passion for literature and especially for poetry was always somehow an organic part of our seemingly frivolous pastimes. Despite the difficult times, the often poor teachers (though there were good ones, too), and our seemingly unserious attitude toward life, this passion continued to develop and grow stronger. Our guys, especially Yulik and Yan Gorbuzenko, were magnificent at reciting poetry.

I am very ashamed to admit that I had a distorted view of Yulik's character back then. The “direct nobility of his soul” did not move me, and his womanizing, which was a very important quality for him, I disliked. And his self-reliance and firmness, his heroic and solitary courage, went unnoticed by me. I (like everyone else) only acknowledged his undeniable charm.

Once, when Yulik’s activities were in full swing, I started a conversation about him with Arkady Filatov. Arkady was frequently in Moscow at the time and saw Yulik much more often than I did. I said that I didn't understand his life: he was a talented man, yet he was wasting himself on God knows what (translating worthless poets). Arkady knew everything and was choking on his indignation, but of course, he couldn't answer me, who knew nothing.

Yulik transferred to Moscow, as I’ve already mentioned, and a couple of years later he married Larisa Bogoraz (who certainly deserves her own separate story). But we saw each other frequently—at least once or twice a year: either he would come to Kharkiv, or I would go to Moscow.

After working for two years as teachers by assignment, my friends returned to Moscow. Yulik took up translating Caucasian poets from literal versions. Lara enrolled in graduate school, and then, after defending her dissertation in structural linguistics, she went to work in Novosibirsk. My friends’ lives seemed to be proceeding normally.

Yulik and Larisa’s home, first on Armyansky Lane and later on Leninsky Prospekt, was unusually magnetic. I can, for example, tell you how another Yulik from our group, Yulik Krivykh, once went to Moscow to buy himself a coat. He entered Yulik and Larisa’s house—and stayed there, without leaving for a single minute, until his departure.

Once, on a trip to Moscow, I bought my children a very interesting game called “vertalina,” and we tirelessly worked on mastering it until about two in the morning. And then we suddenly started talking about politics. “Marlenka!” the pair of them yelled at me. “Don’t get involved in politics! Politics is blood and filth!”

On August 29, 1965, Yulik, suddenly and unannounced, as he liked to do, arrived right on my birthday. And then, like jack-in-the-boxes, two men appeared whom I had long suspected of being informers. I whispered this to Yulik. But I assumed, of course, that they had come for me. We started reading poems in a circle. When my turn came, I read a poem that I considered risky. I.O. (one of the “snitches”) pretended to be delighted and kissed me. And that’s when my husband “stepped in.” Completely drunk and even slurring his words, he shouted, “Get out of my house! I won’t have a stranger kissing my wife!”

In short, they left. “Old man!” Yulik said. “What was that?” My husband looked at him with perfectly sober eyes. “Well, they had to be kicked out!” he said. The next day, Yulik left for Novosibirsk, where Larisa was working at the time.

Not a single suspicion crossed my mind. Two weeks later, my Kharkiv friend Alik Volkov, a professor at the conservatory, came to see me. “Daniel was arrested in Moscow yesterday.” What it was about, Alik, of course, did not know.

I was stunned. If they arrested Yulik, it meant they had started jailing people “for loose talk” again—that was as far as my assumptions went. On my way to work, I took my thirteen-year-old son Zhenya with me. Briefly telling him what had happened, I told him not to believe anything they would say about Yulik, or about me, if the same thing happened to me.

Several months passed, and we found out everything. We found out about “Tertz” and “Arzhak.” Yulik served his five years and then three years with restricted rights in Kaluga, where we used to visit him. For all five years, our “correspondence” never stopped. I put this word in quotes because I was the one writing to him. He, when the time came to write letters (two a month, and one every two months when he ended up in the Vladimir Prison), would reply to everyone at once, and in Moscow, these “letters” would be transcribed for his correspondents. At first, Lara did this, and when she was also sent into exile for participating in the demonstration against the occupation of Czechoslovakia, others took over: Marina Domshlak and Yura Gerchuk (known at home as “the Fayums”) were the best at it. His letters were remarkable! They were later published as a separate book.

On holidays, Yulik was sometimes allowed to write greeting cards—so I received them a few times as well…

Upon his return to Moscow, Yulik was also forced to endure the collapse of his family, which had begun even before his arrest. He married Irina Pavlovna Uvarova, tried to translate, tried to write—but it was all to no avail.

Писал стихи зело борзо

в тюрьме, в бараке и в ШИЗО,

а вольным был – и год от году

терял хорошие слова:

мораль сей жизни такова:

поэтам НЕ нужна свобода.

There is a great deal of truth in this joke of his. Only extreme circumstances—including the years spent in a kind of “co-authorship” with Andrei Sinyavsky (or rather, not co-authorship but “co-writing”), and then the years of unfreedom—stirred Yulik’s literary talent; the rest of the time, this talent lay dormant. Though he did try to write something during his “free” years. But in the end, he had one book: the prose written in the first half of the 1960s, and the poems written in the camp and prison. Although not much was written, it was very powerful.

Much later, I learned from Larisa exactly how he was arrested. Sensing his arrest was imminent due to a number of signs, Yulik went to see Lara (he had stopped in Kharkiv before that to say goodbye to me as well). In Novosibirsk, some “art historian in plain clothes” appeared almost immediately, categorically insisting that he travel to Moscow. Their plane tickets were for seats next to each other (touching, isn’t it?). Lara immediately bought a ticket for the same flight. They tried to ask the “art historian” to give her the seat, but it didn't work. Then she asked a neighbor of hers on the plane, and he swapped with Yulik—and they spent the entire long flight together. He was arrested right at the airport, but at that moment he felt that one of the KGB men had been disrespectful to his wife, so he broke free and lunged at the man with his fists.

After the arrest of Yulik and Andrei, a gradual movement of protest against a trial that was unjust to the point of being comical began to emerge, giving rise to the so-called “dissident movement.” But Yulik always dissociated himself from it. “I’m not a dissident, I’m a lone wolf,” he would say. Once, long before the events described here, the three of us were talking; the third person was Yulik’s closest friend, Misha Buras. Yulik said: “If I had known they could jail me, I would have rather killed myself beforehand. I can’t endure the camps!”

He knew what he was talking about! His health could not withstand all of it: the camp, and then the Vladimir Prison. In the first years after his release, he didn't correspond with anyone—he only wrote to his fellow prisoners back in the camp. Every night, though he was free and for a time even celebrated, he dreamed of the camp. Very soon, he fell ill, was sick for a long and difficult time, and died at only 63 years of age, and his death was a very hard one.

Here is one of my last poems to Yulik.

Где ты, спутник мой любимый,

баловень ушедших лет?

Погляди, какие дымы

ты развел себе вослед!

Погляди, какие люди

на свидание с тобой

привалили - помнят, любят!

Каждый со своей судьбой,

но к тебе пришли, желая

вновь почуять близость плеч,

в памяти своей сжимая

облик твой, и смех, и речь,

и в душе своей сжигая

то, что следовало сжечь!