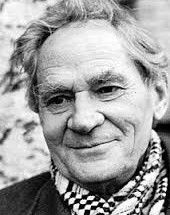

On January 9, Boris Alekseyevich Chichibabin (1923–1994) would have turned 100. In recent years, what I have always known has become increasingly clear—he was a great poet. And today, many of his poems are needed by people even more than they were 35–40 years ago, when he reached a wider readership.

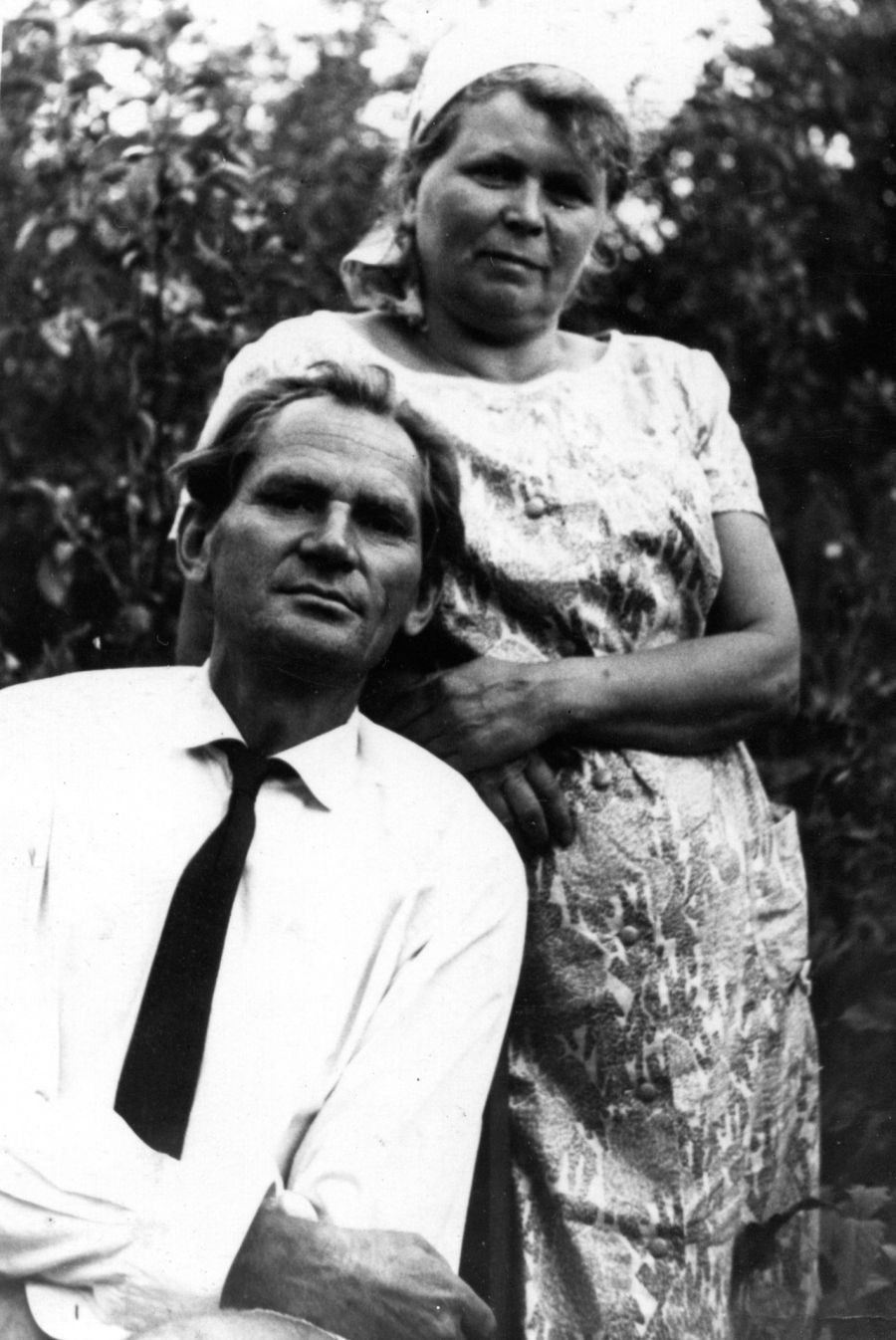

As it happened, I knew him from the late 1950s, when I was still a child. Our families were friends for many decades, and we also lived very close to each other. At first, in the center of Kharkiv: we were on Podgornaya Street, and he, with his wife at the time, Matilda Fyodorovna Yakubovskaya, “Motik,” lived on the corner of Rymarskaya Street and Bursatsky Descent. My sister Sasha and I called them “Auntie Motik, Uncle Borik.” Then in May 1966, we moved to the Novyye Doma district and lived at the beginning of Stadionnyy Passage, but Borya soon also moved in with his new wife, Lilia Semyonovna Karas, “Lilichka”—a five-minute walk from each other. And throughout all those years, Boris would visit us two or three times a week, no less. I was fortunate enough to be, along with my parents, among the first listeners (after his wives, of course) of his newly written poems.

In short, it’s high time to write a memoir. But this cursed war has turned everything upside down, and in my work, I’ve had to deal with things entirely different from what I had planned—documenting war crimes, helping victims of the war, etc. And besides, for obvious reasons, the Russian language is not held in high regard by Ukrainians right now. Nevertheless, I consider it my duty to relate at least a few details because, God forbid, I might die—“a mortal age”—and there will be no one left to remember them. I have no time at all, so this will only be a few fragments related to specific poems. God willing, someday I will write more.

* * *

Boris was imprisoned in the summer of 1946. Both my mother, Marlena Rakhlina, and her younger brother, Felix Rakhlin, confidently asserted that it was for the poems with the refrain “My mother is the governor,” which were undoubtedly seditious: what else could you call lines like “Burn, burn to the ground, O song of stabbing, // Lest a new Yezhovshchina come upon our land.” The arrest, and what followed, is described in their memoirs, *What Was—We Saw...* and *About Boris Chichibabin and His Time*. Mama remembered “Posadnitsa” by heart, and I wrote these verses down a long time ago, back in the late 60s, and also memorized them. Here they are.

Что-то мне с недавних пор

на земле тоскуется.

Выйду утречком во двор,

поброжу по улицам,

погляжу со всех дорог,

не видать ли празднества.

Я – веселый скоморох,

мать моя посадница.

Ты не спи, земляк, не спи,

разберись, чем пичкают.

И стихи твои, и спирт –

пополам с водичкою.

Хватит пальцем колупать

в ухе или в заднице!

Подымайся, голытьба,

мать моя посадница!

Не впервой нам выручать

нашу землю отчую.

Паразитов сгоряча

досыта попотчуем:

бюрократ и офицер,

спекулянтка-жадница –

всех их купно на прицел,

мать моя посадница!

Пропечи страну дотла,

песня-поножовщина,

чтоб на землю не пришла

новая ежовщина!

Гой ты, мачеха-Москва,

всех обид рассадница:

головою об асфальт,

мать моя посадница!

А расправимся с жульем,

как нам сердцем велено,

то-то ладно заживем

по заветам Ленина!

Я б и жизнь свою отдал

в честь такого празднества,

только будет ли когда,

мать моя посадница?!

But what’s interesting is this: Boris never read them aloud or published them. Felix recalls in his book that once, in a large company, he reminded Boris of the reason for his imprisonment, and Boris did not object but, on the contrary, immediately recited the poem by heart. And yet he never published it! Meanwhile, he wrote two different poems using this refrain and published them under the title “A Song for All Time,” incorporating entire lines, rhymes, and themes from the original version. Why he tried to hide the first version is a mystery to me. In his book about Boris, Felix compares all three versions and offers some hypotheses. And I will just provide a link here to the first reading of “The Song” in Kyiv in 1990. He read poetry beautifully, literally mesmerizing his audience.

* * *

I clearly remember how struck I was by Boris’s poems “Stalin Is Not Dead” and “Crimean Strolls,” written around the same time, in 1959. He read them at our house. A little later, he read them publicly at the Central Lecture Hall, where poetry readings were regularly held in the late 50s and the first half of the 60s. I remember the frenzied ovation from the packed hall.

Boris was actually a shy and indecisive man, but he always read his poems willingly, without fear, and let anyone who wanted to copy them down. No dinner party was complete without his readings.

“Stalin Is Not Dead” is well-known—perhaps it is Boris’s most famous poem—but “Crimean Strolls” is less familiar. I will include this remarkable poem here.

Колонизаторам — крышка!

Что языки чесать?

Перед землею крымской

совесть моя чиста.

Крупные виноградины…

Дует с вершин свежо.

Я никого не грабил.

Я ничего не жег.

Плевать я хотел на тебя, Ливадия,

и в памяти плебейской

не станет вырисовываться

дворцами с арабесками

Алупка воронцовская.

Дубовое вино я

тянул и помнил долго.

А более иное

мне памятно и дорого.

Волны мой след кропили,

плечи царапал лес.

Улочками кривыми

в горы дышал и лез.

Думал о Крыме: чей ты,

кровью чужой разбавленный?

Чьи у тебя мечети,

розвища и развалины?

Проверить хотелось версийки

приехавшему с Руси:

чей виноград и персики

в этих краях росли?

Люди на пляж, я — с пляжа,

там, у лесов и скал,

Где же татары?» — спрашивал,

все я татар искал.

Шел, где паслись отары,

желтую пыль топтал,

«Где ж вы, — кричал, — татары?»

Нет никаких татар.

А жили же вот тут они

с оскоминой о Мекке.

Цвели деревья тутовые,

и козочки мекали.

Не русская Ривьера,

а древняя Орда

жила, в Аллаха верила,

лепила города.

Кому-то, знать, мешая

зарей во всю щеку,

была сестра меньшая

Казани и Баку.

Конюхи и кулинары,

радуясь синеве,

песнями пеленали

дочек и сыновей.

Их нищета назойливо

наши глаза мозолила.

Был и очаг, и зелень,

и для ночлега кров...

Слезы глаза разъели им,

выстыла в жилах кровь.

Это не при Иване,

это не при Петре:

сами небось припевали:

«Нет никого мудрей».

Стало их горе солоно.

Брали их целыми селами,

сколько в вагон поместится.

Шел эшелон по месяцу.

Девочки там зачахли,

ни очаги, ни сакли.

Родина оптом, так сказать,

отнята и подарена, —

и на земле татарской

ни одного татарина.

Живы, поди, не все они:

мало ль у смерти жатв?

Где-то на сивом Севере

косточки их лежат.

Кто помирай, кто вешайся,

кто с камнем на конвой, —

в музеях краеведческих

не вспомнят никого.

Сидит начальство важное:

«Дай, — думает, — повру-ка».

Вся жизнь брехнею связана,

как круговой порукой.

Теперь, хоть и обмолвитесь,

хоть правду кто и вымолвит, —

чему поверит молодость?

Все верные повымерли.

Чепухи не порите-ка.

Мы ведь все одноглавые.

У меня — не политика.

У меня — этнография.

На ладони прохукав,

спотыкаясь, где шел,

это в здешних прогулках

я такое нашел.

Мы все привыкли к страшному,

на сковородках жариться.

У нас не надо спрашивать

ни доброты, ни жалости.

Умершим — не подняться,

не добудиться умерших...

Но чтоб целую нацию —

это ж надо додуматься...

А монументы Сталина,

что гнул под ними спину ты,

как стали раз поставлены,

так и стоят нескинуты.

А новые крадутся,

честь растеряв,

к власти и к радости

через тела.

А вражьи уши радуя,

чтоб было что писать,

врет без запинки радио,

тщательно врет печать.

Когда ж ты родишься,

в огне трепеща,

новый Радищев —

гнев и печаль?

* * *

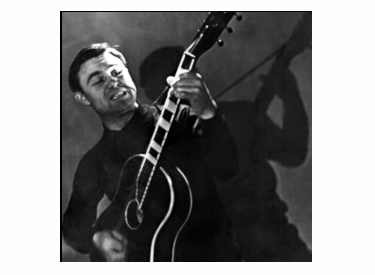

My entire childhood and youth were spent to the sound of the guitar and the wonderful baritone of Alexey Pugachev—Leshka, as everyone called him—an incredibly talented man: an actor, a singer, an artist. He wrote and sang songs based on the poems of his friends—most of all, Boris’s poems. Boris wrote captions for Leshka’s paintings (Leshka called them “pictures”) in the form of sonnets. Leshka turned them into songs, calling the cycle “Sonnets from an Album.” In Boris’s books, they are included under the title “Sonnets for Pictures” along with many other sonnets from a later period, but if I’m not mistaken, they were never published separately. So I will at least list here the sonnets that Leshka sang: “Sails,” “Evening After Payday,” “The Bed,” “Autumn,” “I Don’t See, I Don’t Hear, I Don’t Want to Know,” and “The Old Storekeeper.” There were many more pictures. I have long wanted to produce an edition like this: reproductions of Leshka’s pictures, the sonnets for them, and a disc with recordings of Leshka’s songs based on these and other poems by Boris. But I never did it: I had neither the time nor the money. However, kind people have taken care of it: some of Leshka’s songs are available on the internet, including those set to Boris’s words, such as the famous “Red Tomatoes” and “Makhorka,” as well as some of the sonnets for the pictures.

I will share my favorite sonnet here—“Sails.” Leshka’s picture for it was like this: a sad, middle-aged sailor in a striped shirt stands next to laundry flapping in the wind on a clothesline. I believe Boris wrote it sometime in ’61 or ’62.

Есть в старых парусах душа живая.

Я с детства верил вольным парусам.

Их океан окатывал, вздувая,

и звонкий ветер ими потрясал.

Я сны ребячьи видеть перестал

и, постепенно сердцем остывая,

стал в ту же масть, что двор и мостовая, —

сказать по-русски — крышка парусам.

Иду домой, а дома нынче — стирка.

Душа моя состарилась и стихла.

Тропа моя полынью поросла.

Мои шаги усталы и неловки,

и на простой хозяйственной веревке

тряпьем намокшим сохнут паруса.

* * *

Recently, on the Facebook page of my friend, the poet and translator Yura Yefremov, I saw Boris’s poem “May God Grant You from Roots to Crown...” and saw a view expressed in the comments: it’s as if it were written today. And I remember well how and when this poem was written and first read; I was there listening. It is connected with the departure of friends from Kharkiv to Israel. It was either March 13 or 14, 1971, I don’t remember exactly. There was a farewell for the families of Lina and Alik Volkov and Fima and Olya Spivakovsky—a sea of people in the Volkovs’ small, two-room apartment in a *khrushchyovka*, not far from Boris and from us, on the same Tankopiya Street. Boris wrote this poem for Lina and Alik that very day and read it in the evening. Everyone present copied it down, and it instantly spread throughout the entire country.

Дай вам Бог с корней до крон

без беды в отрыв собраться.

Уходящему — поклон.

Остающемуся — братство.

Вспоминайте наш снежок

посреди чужого жара.

Уходящему — рожок.

Остающемуся — кара.

Всяка доля по уму:

и хорошая, и злая.

Уходящего — пойму.

Остающегося — знаю.

Край души, больная Русь,—

перезвонность, первозданность

(с уходящим — помирюсь,

с остающимся — останусь) —

дай нам, вьюжен и ледов,

безрассуден и непомнящ,

уходящему — любовь,

остающемуся — помощь.

Тот, кто слаб, и тот, кто крут,

выбирает каждый между:

уходящий — меч и труд,

остающийся — надежду.

Но в конце пути сияй

по заветам Саваофа,

уходящему — Синай,

остающимся — Голгофа.

Я устал судить сплеча,

мерить временным безмерность.

Уходящему — печаль.

Остающемуся — верность.

Boris generally took the emigration of his friends from the USSR painfully (“I will not go to foreign lands”). And when Alexander Galich was forced to leave (that was on June 25, 1974), he wrote the poem “Not Believing in the Blood Covenant...”—there is an error in the dating in Boris’s books: it should be 1974, not 1973. Boris came to our place, read it, and I immediately typed it up. The next day I was leaving for Moscow. There I showed the poem to Larisa Bogoraz (incidentally, the poem “I Call to You, Without Parting My Lips” was written for her), and she said, “The land is dead. A scorched earth.” When I returned, I told Boris about this. He grew grim but said nothing. The next day he brought the poem back with a fourth stanza added; it hadn't been in the first version. And I remember exactly what it said: “And if it’s dead—then what the hell // Is the point of living?” And he read it in that version. Perhaps he corrected it later.

Не веря кровному завету,

Что так нельзя,

Ушли бродить по белу свету

Мои друзья.

Броня державного кордона —

Как решето.

Им светит Гарвард и Сорбонна,

Да нам-то что?

Пусть будут счастливы, по мне, хоть

В любой дали.

Но всем живым нельзя уехать

С живой земли.

С той, чья судьба ещё не стерта

В ночах стыда.

А если стёрта, то на черта

И жить тогда?

Я верен тем, кто остаётся

Под бражный трёп

Своё угрюмое сиротство

Нести по гроб.

Кому обещаны допросы

И лагеря,

Но сквозь крещенские морозы

Горит заря.

Нам не дано, склоняя плечи

Под ложью дней,

Гадать, кому придётся легче,

Кому трудней.

Пахни ж им снегом и сиренью,

Чума-земля.

Не научили их смиренью

Учителя.

В чужое зло метнула жизнь их,

С пути сведя,

И я им, дальним, не завистник

И не судья.

Пошли им, Боже, лёгкой ноши,

Прямых дорог,

И добрых снов на злое ложе

Пошли им впрок.

Пускай опять обманет демон,

Сгорит свеча, —

Но только б знать, что выбор сделан

Не сгоряча.

* * *

The poem “Ode to a Sparrow” is dated 1977 in Boris’s books. But it was written in 1973, sometime in the spring, under the following circumstances.

On January 9, 1973, Boris turned 50. Long before that, the poet Zelman Katz came to him and proposed organizing a poetry reading at the Writers’ Union for his anniversary. Zelman Mendelevich loved Boris’s poetry and genuinely wanted to celebrate the anniversary of a colleague, a member of the Writers’ Union. Boris agreed, and he read many poems at the event. And although the most provocative ones were not among them, what he did read was enough to trigger official repercussions. There was a certain lady at the reading from the district party committee, or maybe the city committee—I no longer remember. The Writers’ Union held a meeting that no one was allowed to attend, only the leadership. Boris was accused over “Be Damned, Emperor Peter!” and “In Memory of A.T. Tvardovsky” and was expelled from the Union. Poor Katz, as the event’s organizer, was thoroughly picked apart. I think he was used to create a pretext for the expulsion.

And then Borya grew somewhat despondent. Although it might seem he had no reason to—he never frequented the Writers’ Union, had long since returned “to serve in the tramway authority,” had drowned his union card in the Dnieper, and could no longer get new books published nor even wanted to (he ended a long, heartfelt inscription to my parents in his 1968 book *Avrora Sails* like this: “...as for the book, I won’t do it anymore”)—he nevertheless took his excommunication from the official literary world painfully. But then he wrote “Ode to a Sparrow”—and felt better; he stopped agonizing over the expulsion. Look at this wonderful poem from that perspective.

ОДА ВОРОБЬЮ

Пока меня не сбили с толку,

презревши внешность, хвор и пьян,

питаю нежность к воробьям

за утреннюю свиристелку.

Здоров, приятель! Чик-чирик!

Мне так приятен птичий лик.

Я сам, подобно воробью,

в зиме немилой охолонув,

зерно мечты клюю с балконов,

с прогретых кровель волю пью

и бьюсь на крылышках об воздух

во славу братиков безгнездых.

Стыжусь восторгов субъективных

от лебедей, от голубей.

Мне мил пройдоха воробей,

пророков юркий собутыльник,

посадкам враг, палаткам друг,—

и прыгает на лапках двух.

Где холод бел, где лагерь был,

где застят крыльями засовы

орлы-стервятники да совы,

разобранные на гербы,—

а он и там себе с морозца

попрыгивает да смеется.

Шуми под окнами, зануда,

зови прохожих на концерт!..

А между тем не так он сер,

как это кажется кому-то,

когда из лужицы хлебнув,

к заре закидывает клюв.

На нем увидит, кто не слеп,

наряд изысканных расцветок.

Он солнце склевывает с веток,

с отшельниками делит хлеб

и, оставаясь шельма шельмой,

дарит нас радостью душевной.

А мы бродяги, мы пираты,—

и в нас воробышек шалит,

но служба души тяжелит,

и плохо то, что не пернаты.

Тоска жива, о воробьи,

кто скажет вам слова любви?

Кто сложит оду воробьям,

галдящим под любым окошком,

безродным псам, бездомным кошкам,

ромашкам пустырей и ям?

Поэты вымерли, как туры,—

и больше нет литературы.

And although the aurochs haven’t died out but are briskly running through the mountains, the poem is still wonderful!

Let these short notes serve as at least a small tribute to the memory of a remarkable poet and a dear friend, the only person who ever called me, “Zhenechka, my dear!”