Perhaps the most notable underground organization of the 1970s was the “Ukrainian National Liberation Front” (UNVF). It was formed in the city of Sambir, Lviv region.

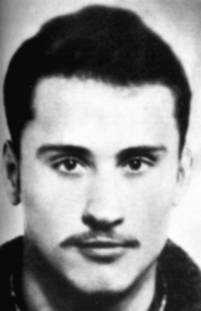

The main actor and leader of the UNVF can rightly be considered Zorian Popadiuk, initially a schoolboy and later a young student in the Ukrainian philology department at Lviv University. His mother, Lyubomyra Popadiuk, belonged to the circle of Western Ukrainian dissident shestydesiatnyky (Sixtiers) and was acquainted with Viacheslav Chornovil, Ivan Hel, the Horyn brothers, and others[1]. Zorian was raised in a corresponding environment, with a corresponding value system. Even while in school, he reprinted samizdat with his mother.

The events in Czechoslovakia in 1968 had a strong influence on Zorian. He recalls that it was then that he and his friends decided to form an underground organization:

“And in fact, it was then, in 1968, and probably further in 1969, that we made our first attempt to create a youth organization. I gathered my school friends, or even classmates—there were about eight of them, and the eight of us created an organization that we pretentiously named: ‘The Ukrainian National Liberation Front.’ And why? Because there was the Ukrainian National Front, to which Mykhailo Diak, Kvetsko, Krasivsky, and so on belonged. They were arrested—we knew that, and we took that name so that the front would continue to exist. And so we gathered in the yard near my house, there was a bench and a chair, and we wrote ourselves a program, the text of an oath or pledge, made and glued together a flag... It was blue-and-yellow with a trident. Since that organization could operate like that, when the first anniversary of the entry of Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia came, we marked it with leaflets. We wrote those leaflets by hand, printed some of them, and that was enough for us to paste them all over Sambir”[2].

The founders of the UNVF also included Yaromyr Mykytko, Hennadiy Pohorelov, Omelyan Bohush, Yevhen Senkiv, Ihor Kovalchuk, and Dmytro Petryna; Oleksandr Ivantso soon joined them[3]. They agreed to pay membership dues—5 rubles a month. One of the first actions of the UNVF was to place a plaque at the city cemetery in memory of the victims of the NKVD. Zorian Popadiuk and his friends were involved in distributing samizdat, particularly the works of Valentyn Moroz. After the “great pogrom” of 1972, Zorian decided that the movement had been crushed and that the “thankless” work needed to be intensified to continue. He bought a typewriter and began to produce and distribute leaflets with other members of the UNVF. The content of the leaflets was independence for Ukraine and other enslaved nations. During the arrests of the Sixtiers, Zorian’s apartment was searched. For arguing with KGB officers, he was expelled from the university. In the autumn of 1972, the first issue of the journal “Postup” (Progress)—an old idea of Zorian’s—was published. His main colleague on this front was Zorian’s friend, also a student of the philology faculty at Lviv University, Hryhoriy Khvostenko. He wrote under the pseudonym M. Sohoden, and later—P. Yatahan. He was the author of a number of bold political and literary articles published in “Postup”: “Our Principles,” “The Roots and Flowers of Russian Chauvinism,” “Outlines of the Real Hrabovsky,” etc.[4]. Other materials for “Postup” were prepared by Zorian Popadiuk. One page of the journal was dedicated to a “Chronicle of Repressions.” Famous samizdat works by the Sixtiers were also published, such as Ivan Hel’s article “Totalitarianism, the Ukrainian Renaissance, and Valentyn Moroz,” as well as poems.

Through H. Khvostenko, contact was established with a group of history students at Lviv University who studied the history of Ukraine based on primary sources, not on official Soviet historians. This “historical link” of the UNVF included Stepan Sluka, Ihor Khudyi, Ivan Svarnyk, Ihor Kozhan, Maryana Dolynska, Leonid Filonov, and Roman Kozovyk[5].

On March 28, 1973, the UNVF carried out an action in Lviv. During the night, 250 leaflets were scattered in protest against the authorities’ ban on celebrating Shevchenko Days. Zorian Popadiuk, Hryhoriy Khvostenko, and his girlfriend Nadiya Stepula took part in making the leaflets, while Yaromyr Mykytko, Roman Romodan, and members of the UNVF’s “historical link” distributed them. But within a few hours of the action, all its participants and organizers were in the clutches of the KGB. Criminal cases were opened separately against the UNVF, separately against the history students, and separately against H. Khvostenko, because he actively cooperated with the investigators. About 50 students were found to be involved in the case. The repressions were as follows: 15 students were expelled from the university, H. Khvostenko received a 5-year suspended sentence[6], and Zorian Popadiuk and Yaromyr Mykytko were convicted under Articles 62 part 1 and 64 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR. Popadiuk was given 7 years of imprisonment in strict-regime camps plus 5 years of exile, and Mykytko received 5 years in strict-regime camps[7].

The UNVF was undoubtedly a new phenomenon in the resistance movement, primarily from the point of view of political thought. The young people who chose the underground path of struggle were raised on the samizdat of the Sixtiers, but in their understanding and assessments, they outgrew them; they represented a new generation of Ukrainian dissidents. Thus, A. Rusnachenko considers the article “Our Principles” in the first issue of “Postup” “an attempt to say in a full voice what Ivan Dziuba failed to say”[8]. In it, Hryhoriy Khvostenko views the USSR as a regressive state from the point of view of the historical process. The reason for this is, firstly, the striving for world hegemony, and secondly, the suppression of freedom of thought and the advance of Russian chauvinism within the union. Mykhailo Kheyfets in “Ukrainian Silhouettes” dedicated a chapter to Zorian Popadiuk. It seems appropriate to give an example from “Ukrainian Silhouettes” that beautifully demonstrates the continuity and at the same time the new level of the national resistance movement in Ukraine through the example of two of its representatives—Dmytro Kvetsko and Zorian Popadiuk. We ask the reader’s forgiveness for the long quotes. “Dmytro fondly recalled that Ukrainians live in the Kuban and that ‘our lands’ are there, and he listened without any pleasure to me saying that if foreign lands, colonized by newcomers, become ‘ours,’ then Ukraine itself will have to cede a considerable part of its territory in the future. Of course, these were relics of imperial ideology in him. But it was not for nothing that Dmytro seemed a transitional figure: while indulging in dreams of a great Ukraine ‘from the Black to the Okhotsk Seas,’ as a practical thinker he stood firm on the position of limiting all Ukrainian claims to the territory of the modern UkrSSR: ‘If even the Negroes in Africa managed to understand that the old colonial borders are better than redistributions and the death of new nations, will we not understand this? We must build Ukraine on the land that already exists.’ This was the consciousness growing in him, as in a cocoon, which was fully formed only in the next generation of nationalists, the personification of which for me in this zone became Dmytro’s opponent, Zorian Popadiuk: ‘We stand for the unconditional return by Ukraine of the Crimean Tatars’ national home—Crimea,’ Zorian explained to me”[9].

Zorian argued with Dmytro Kvetsko also about the path Ukraine should take to gain its independence. Zorian insisted on a nationwide referendum, while Dmytro Kvetsko categorically objected: “We are a people of an old culture and ancient statehood, who have never ceased the struggle for their independence. What is this, we laid down hundreds of thousands of people in the struggle for an independent Ukraine, and now we will start voting on whether we need freedom—it turns out that the people who died for freedom before us seemingly died in vain, and we are starting all over again”[10]. “Zorian is a new type of fighter, a human rights activist,” writes Mykhailo Kheyfets, “and for him, the opportunity to rely on the law, not just on force, the opportunity to use a weapon snatched from the hands of the enemy and turn it on his own head, seemed too attractive to refuse in favor of Dmytro’s idealistic concepts... Outwardly, it seemed to me then, Popadiuk’s position contradicted Kvetsko’s, but in essence—it continues it in the history of the people. The people grew up, matured, and, younger than them, feeling this with nerve and soul, formulated new tasks for the nation”[11].

M. Kheyfets’s observations best reflect the evolution of political thought among nationalists of different countries; he also mentions the dispute over the referendum in his work “A Prisoner-of-War Secretary” about the fate of the Armenian dissident and nationalist, Paruyr Hayrikyan. And his conclusions regarding the new generation of nationalists are, in my opinion, indisputable: “For them, a referendum is not only, and frankly, not so much a justification for the emergence of an independent national state, but rather an opportunity to involve the entire nation in deciding its fate. They have no doubt about the outcome of a popular vote; for them, this result is a foregone formality. For the young, the very process of educating and maturing the people in the course of deciding their historical destiny is more important”[12].

[1] Audio interview with Z. Popadiuk. Conducted by V. Ovsiyenko // KHPG Archive, 2000, p. 7.

[2] Ibid., p. 9.

[3] Rusnachenko A. Natsionalno-vyzvolnyi rukh v Ukraini: seredyna 1950-kh – pochatok 1990-kh rokiv. – Kyiv: Vydavnytstvo imeni Oleny Telihy, 1998, p. 197.

[4] Ibid., p. 198.

[5] Ibid., p. 199.

[6] Audio interview with Z. Popadiuk. Conducted by V. Ovsiyenko // KHPG Archive, 2000, p. 15.

[7] Ibid., p. 205.

[8] Rusnachenko A. Rozumom i sertsem. Ukrainska suspilno-politychna dumka 1940-1980-kh rokiv. – Kyiv: Vydavnychyi dim “KM Academia,” 1999, p. 211.

[9] Kheyfets M. Op. cit., p. 164.

[10] Ibid., p. 163.

[11] Ibid., p. 163.

[12] Ibid., p. 222.