One of the bright pages in the history of resistance to the Soviet totalitarian regime is the activity of the Ukrainian National Front (UNF). The uniqueness of the UNF lies in its continuity of the national struggle and, at the same time, the presence of a specific, detailed political program, with concrete tasks and steps for achieving its goals, something that had not existed since the time of the OUN-UPA. Unlike all previous underground organizations, the UNF was the first to develop a program that was based neither on the principles of Marxism-Leninism, like the URSS, nor on the principles of integral nationalism, like, for example, the UNK. The UNF program was based on the democratic principles of freedom and equality; it covered all spheres of public life. The UNF was the first underground organization to have a regular periodical, “Volya i Batkivshchyna” (Will and Fatherland).

As D. Kvetsko recalls, it all began in November 1961, when Mykhailo Diak—also born in 1935, a police officer—raised a blue-and-yellow flag in the village of Vytvytsia. “That extraordinary event prompted the history teacher in the village of Kavna, Dmytro Kvetsko, to write a program and other propaganda materials, which were later published in the journal ‘Volya i Batkivshchyna’”[2]. But the beginning of the UNF’s activities can be considered 1964, when Zinoviy Krasivsky joined the cause.

A few words about him. Zinoviy Krasivsky was born in 1930. In 1948, his family was sent to a special settlement in the Karaganda region of Kazakhstan, and their property was confiscated because Zinoviy’s two older brothers had participated in the UPA. But Krasivsky escaped from the train car and lived illegally in Ukraine; he was discovered and sentenced to 5 years in the camps. After an amnesty in 1953, he lived in Karaganda, where he worked as a coalface worker in a mine. He suffered industrial injuries and became a lifelong disabled person of the second group. After returning to Ukraine, he married, graduated from the philological faculty of Lviv University by correspondence, and was the father of two children.

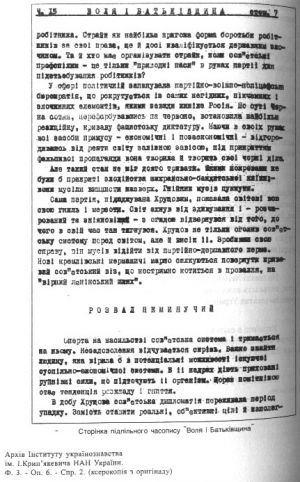

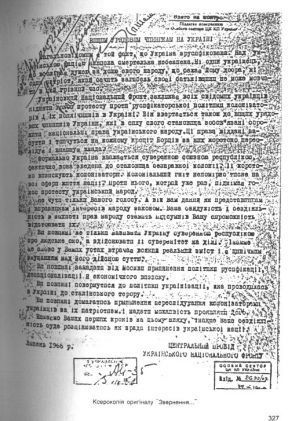

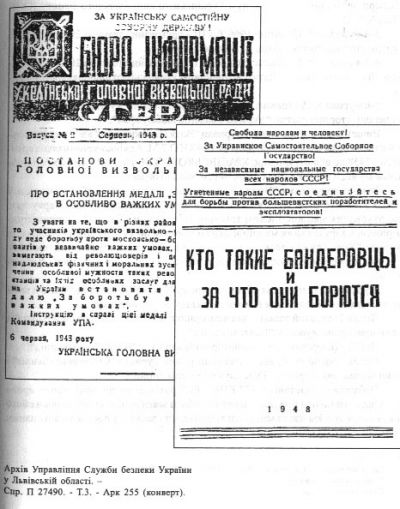

In the summer of 1964, Z. Krasivsky drafted the UNF’s program concept. With Kvetsko’s money, he bought an unregistered typewriter in Moscow. Then Z. Krasivsky made a cliché of the headline “For an Independent Ukrainian State,” below it a trident and the inscription “Freedom for Peoples and for the Individual!” and below that “Published by the Ukrainian National Front.” In October 1964, the first issue of “Volya i Batkivshchyna” was published. The journal published the national front’s program documents, nationalist articles, appeals to the reader, and calls for a liberation struggle, and maintained a permanent section “Ukrainian News.” “Volya i Batkivshchyna” acquainted readers with the attributes of Ukrainian statehood—the anthem, flag, coat of arms, etc. In the summer of 1965, D. Kvetsko found a UPA bunker in the Carpathians and there, many OUN brochures, including: “Who are the Banderites and what are they fighting for,” “Information Bulletin of the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council (UHVR),” “Ukrainian Teachers,” “Ukrainian Children,” “Christ is Born,” etc. The UNF was also involved in distributing these brochures, and the most active in this matter was Mykhailo Diak. “Volya i Batkivshchyna” was initially printed at Krasivsky’s home in Morshyn. For conspiracy purposes, in 1965, the printing of “Volya i Batkivshchyna” was moved from Krasivsky’s apartment to a bunker on the slope of Mount Lyuta. There, a camouflaged hideout was equipped, where Z. Krasivsky and D. Kvetsko printed “Volya i Batkivshchyna,” leaflets, poems, etc. at night. Yaroslav Lesiv, a physical education teacher from the Kirovohrad region born in 1945, and Vasyl Kulynyn, a turner born in 1943, joined the cause. Soon, a Lviv branch of the UNF was created, whose activists were Myroslav Melen, Ivan Hubka, Hryhoriy Prokopovych, M. Kachur, and others.

It seems that such steps by the UNF, although they hastened the arrests, also brought the organization to a completely different level of struggle. This was already a statement from a formed circle of political opposition. As for the arrests, in a sense they were not a defeat but a triumph for the UNF, as nothing promotes the ideas of the opposition as effectively as repressions against it. True, the public did not learn about the repressions against the UNF members immediately due to the same conspiracy and isolation of the national front.

Trials took place. In Ivano-Frankivsk in November 1967, a visiting session of the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR was held. Members of the UNF were charged with treason (Art. 56 part 1) and the creation of an anti-Soviet organization (Art. 64 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR). The sentences were distributed as follows: D. Kvetsko received 15 years, including 5 years in prison and 10 in a strict-regime corrective labor colony, plus another 5 years of exile; Z. Krasivsky was sentenced to 12 years, including 5 in prison and 7 in a strict-regime corrective labor colony, and 5 years of exile; M. Diak received 12 years, including 5 in prison and 7 in a strict-regime corrective labor colony, and 5 years of exile; Y. Lesiv and V. Kulynyn each received 6 years in a strict-regime corrective labor colony. Even before that, in the summer of 1967, trials were held in Lviv. The Lviv regional court, under Art. 62 part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, sentenced M. Melen to 6 years in a strict-regime corrective labor colony and 5 years of exile; I. Hubka to 6 years in a strict-regime corrective labor colony and 5 years of exile; I. Kachur and H. Prokopovych to 5 years in a strict-regime corrective labor colony.

By the time of the arrests, the UNF had managed to recruit many patriots from different regions of Ukraine into its ranks. There are different estimates of the UNF’s size (membership can be defined differently). Myroslav Panchuk, for example, notes that the UNF had over 150 participants. But A. Rusnachenko’s estimates are probably more objective—the UNF had about a dozen active members, two to three dozen readers of “Volya i Batkivshchyna,” and hundreds of readers of *samizdat* and nationalist literature.

One cannot agree with G. Kasyanov, who notes that “The creation and crushing of the UNF showed the impossibility of the existence of an underground organization, even a carefully conspiratorial one...” The underground struggle continued throughout this time; some groups were uncovered, and others appeared in their place. As for the UNF, it did not cease to exist at all; successors were found—the UNF-2. The main mistake of the underground members was the lack of connections with the so-called “mainland” in military partisan strategy. And there were talks about this. Zinoviy Krasivsky spoke of the need to establish contacts with foreign countries. Of course, such attempts could have hastened the exposure of the UNF, but on the other hand, this movement would not have been isolated, and the world community would have learned about the arrests of the UNF members earlier.

Yuriy Zaytsev defines the historical role of the UNF as follows: “The Ukrainian National Front occupies a prominent place in Ukrainian history also because it reflected the needs of the time, became a real bridge between two stages of the pro-independence movement—the armed and the peaceful.” This assessment also seems not entirely accurate. When the UNF was formed, the Sixtiers were already resisting the totalitarian regime. And the first repressions took place in 1965 precisely against them. But some members of the UNF, like Krasivsky, joined the ranks of dissidents and human rights activists while already in captivity. The same happened with some members of the URSS and with many other underground activists, even of an older age—UPA soldiers. But in terms of personalities, Yuriy Zaytsev’s statement is probably correct. Mykhailo Kheyfets, for example, in “Ukrainian Silhouettes,” describes Dmytro Kvetsko as follows: “In character, Dmytro seemed to me the embodiment of a transitional historical type—from people like Kazanovsky, talented, proud, and at the same time unsure of their significance as peasants, to a new breed, personified by Chornovil and his circle of national democrats...”

[1] Ukrainian National Front: Research, Documents, Materials (hereinafter – UNF) / Kvetsko D. From the Years of Struggle (Memoirs) / Comp. M. Dubas, Yu. Zaytsev – Lviv: Institute of Ukrainian Studies named after I. Krypiakevych, NAS of Ukraine, 2000, p. 565.

[2] Ibid., p. 563.

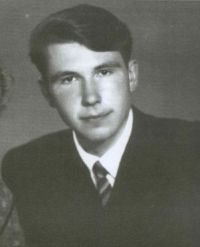

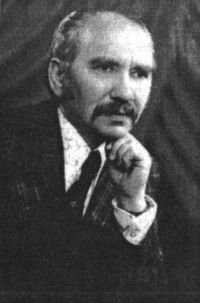

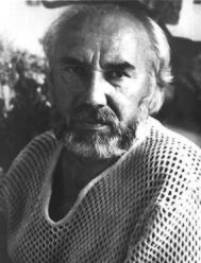

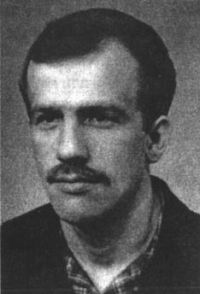

Illustrations (from top):

1. Title header of the journal “Volya i Batkivshchyna”

2. A young Dmytro Kvetsko

3. Portrait of Dmytro Kvetsko painted by Monocharov

4. Dmytro Kvetsko

5. Mykhailo Diak

6, 7. Zinoviy Krasivsky

8, 9. Yaroslav Lesiv

10. Vasyl Kulynyn

11. Myroslav Melen

12. Ivan Hubka

13. Hryhoriy Prokopovych

14. UNF Bofons (currency)

15. Entrance to the hideout where the UNF underground printing press was located

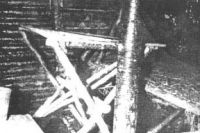

16. Interior of the hideout

Illustrations 1, 7, 8 are taken from the book Ukrainian National Front: Research, Documents, Materials / Comp. M. Dubas, Yu. Zaytsev – Lviv: Institute of Ukrainian Studies named after I. Krypiakevych, NAS of Ukraine, 2000, 680 pp.