On the night of May 1, 1966, a yellow-and-blue flag appeared over the building of the Kyiv Institute of National Economy in Kyiv (now the Kyiv National Economic University) instead of the red one.

The daredevils who raised it had an obvious calculation: here, on Brest-Lytovsky Prospekt, near the “Bolshevik” factory, columns of workers and students would form in the morning to march to Khreshchatyk for the May Day demonstration. Many people would see the flag. However, vigilant retired veterans spotted it earlier and, with fingers trembling from fear and righteous indignation, dialed the number and called “the proper authorities.” The team that arrived feared mines, but near the fire escape, only aviation gasoline had been sprinkled—to prevent a dog from picking up the scent.

The flag quickly ended up at the KGB, at 33 Volodymyrska Street. Moscow ordered the “criminals” to be found and punished. The flag was examined and described. The banner was hand-sewn from two women's scarves. The yellow had a slightly brownish tint: the Soviet government carefully ensured that fabrics of “nationalist colors” did not appear for sale. In the middle, a trident was sewn on, cut from black sateen (a material used for linings). Under the trident, an inscription in block letters, in ink:

Ukraine has not yet perished,

Nor has it yet been killed!

DPU

A criminal case was immediately opened. It took the KGB sleuths more than 9 months to “calculate” the “criminals.” They searched primarily among the full-time students of KINE, then among the evening and correspondence students. Many young men were summoned to the military commissariat and ordered to fill out some forms in block letters. Informants, who operated in every student group, started provocative conversations and monitored reactions and moods. To be suspected, it was enough to be consistently Ukrainian-speaking. Finally, they identified 29-year-old evening student of this institute, Heorhiy Moskalenko, and his friend, 27-year-old worker Viktor Kuksa. They were arrested on February 21, 1967.

In those relatively liberal times of Brezhnev's rise and Petro Shelest's rule in Ukraine, the young men received a small punishment: Moskalenko 3 years, and Kuksa 2 years of imprisonment in strict-regime camps for “especially dangerous state criminals.” The charge was Part I of Article 62 – “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” And as an “add-on” – Article 222, “cold and firearms.” The cold weapon was an ordinary kitchen knife with which Viktor Kuksa cut down the red flag (“You should have gnawed it with your teeth!” said the investigator). The firearm was a homemade pistol, loaded with sulfur from matches. Heorhiy Moskalenko was supposed to use it to give a signal to his friend if any danger arose.

In accordance with the Law of the UkrSSR “On the Rehabilitation of Victims of Political Repressions in Ukraine” of April 17, 1991, by a resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of Ukraine of May 20, 1994, the court decisions regarding the conviction of Moskalenko, H.M. and Kuksa, V. I. under Article 62, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR were overturned, and the criminal case in this part was closed on the basis of clause 2 of Article 6 of the CPC of Ukraine due to the absence of corpus delicti. But they are still considered convicted under Article 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR... Thus, political rehabilitation turned them into ordinary criminals! Such is the paradox of post-Soviet jurisprudence.

And this fact is not isolated: Volodymyr Marmus and his friends also raised 4 national flags and 19 leaflets in Chortkiv, Ternopil Oblast, on the night of January 22, 1973. They were all also rehabilitated under Article 62. But one boy, Petro Vitiv, was only 16 years old. He was not tried. But V. Marmus got an “add-on” charge of “involving a minor in criminal activity.” That is, the crime is no longer there, but the “involvement in criminal activity” remains... And how many people are still not rehabilitated, for whom criminal cases were cynically fabricated for political motives – “resistance to the police,” “drugs,” “attempted rape”!

This is why on March 18, 2002, a Public Committee for the Rehabilitation of the “May Day Duo” was created in Kyiv. It included the co-chairman of the Kyiv Council of Citizens' Associations, Serhiy Tauzhnyansky; the head of the Kaharlyk district organization of the Green Party of Ukraine, Volodymyr Hrysiuk; myself, Vasyl Ovsienko, a former political prisoner, now a program coordinator for the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; and the head of the Kyiv regional organization of the DemPU, former political prisoner Valeriy Kravchenko, who, in fact, initiated this case. After all, Moskalenko and Kuksa signed the flag with the abbreviation “DPU.” It is certain that the “Democratic Party of Ukraine” existed then only in their dreams, and they knew the text of the anthem, but they wrote not for the demonstrators, but for those who would take down the flag. But they became, as it were, harbingers of this future party.

The Committee set itself the task of creating a precedent for the full rehabilitation of these two repressed individuals, in order to later seek the rehabilitation of the entire designated category. Because in our state, which is so far only nominally Ukrainian, everything must be wrested with teeth from the enemies of this state who have remained in power, just so as not to yield it to true patriots. Soviet communist judges, “having noticeably twisted their snouts to the side” (M. Saltykov-Shchedrin), have seated themselves under the blue-and-yellow flag and trident, while the heroes who affirmed these symbols are still criminals to them. Mr. Leonid Kuchma, who in his worst nightmares never dreamed that he would one day become the President of Ukraine, recognizes as persons with special merits to Ukraine – who would you think? Heroes of the Soviet Union, Heroes of Socialist Labor, deputies of the Supreme Soviets of the USSR and the UkrSSR. That is, by and large, the most ardent opponents of Ukraine's independence and the most faithful servants of the Russian occupation authorities.

This is just one of the paradoxes of the transitional era, and there are many. For example, the Ukrainian state pays pensions to the Russian occupiers of Afghanistan and honors them as war veterans. The shameful mercenaries who went to serve our historical enemy on the Russian submarine “Kursk” and perished there are honored as heroes in Ukraine.

> But the brethren are silent,

Their eyes wide open!

Like lambs. “Let it be,” they say,

“Maybe it should be so.”

The intelligentsia, which should be the conscience of the nation, remains silent even when the President, having gone to Siberia, slaps his own people in the face: “We, Ukrainians, are a people with a bit of a screw loose,” and calls the Ukrainians there “khokhols.” A full-fledged nation would have swept away such a president the very next day! Or: Lviv scientists award the plagiarist Volodymyr Lytvyn the degree of doctor “honoris causa.” Because it’s “somehow inconvenient” to offend high-ranking boors with the truth. That is, the “brethren” hope to build Ukraine on a lie, and somehow it will be. But such a Ukraine will not stand! And we don't need such a Ukraine – built on lies!

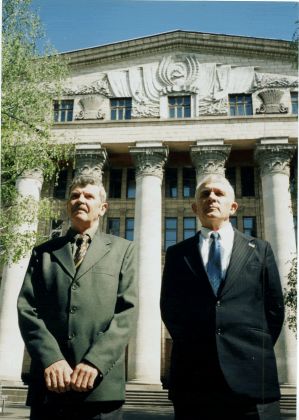

Who are they, these true heroes of Ukraine, who dared to remind Ukrainians of their national symbol at a time when it seemed to have been forgotten? Here is what they told me on March 18 and April 10, 2002.

Heorhiy Mytrofanovych MOSKALENKO was born in Odesa on July 24, 1938. He lived in his mother's village near Odesa, where Galician resettlers had been brought. He was interested in history, knew about the Ukrainian People's Republic, and read Ukrainian literature. In 1955, he went to Kyiv, where he lived in a dormitory in Sviatoshyn and worked as a plumber on a construction site. From 1957-60, he served in the army. This was the era of national liberation movements and the collapse of the world colonial system. The idea that a country as economically strong as Ukraine could and should also be an independent state, at least like Czechoslovakia or Hungary, was completely natural for him.

Viktor Ivanovych KUKSA was born on February 13, 1940, in the village of Savarka, on the Ros River, in the Bohuslav Raion of Kyiv Oblast. His father, an intelligent peasant but not a communist, was the head of the village council, and during the German occupation, he was left behind by the Soviet authorities for underground work. He saved young people from being sent to Germany, for which he was sentenced to death but escaped. Viktor was lucky with his teachers: they bypassed the ideological silt and raised the children as Ukrainians. The music teacher, Dmytro Yevdokymovych Chaly, was sentenced to 25 years and served time in Kolyma. The future academician Lyulka studied at this school, and the later repressed famous mathematician Academician Mykhailo Kravchuk taught here. His mother's stepfather, Oleksandr Ronsky, also served 20 years. From childhood, Viktor knew “Shche ne vmerla Ukraina...” After graduating from school in 1957, he went to Kyiv for construction work, and after serving in the army, he returned to the dormitory in Sviatoshyn.

Heorhiy and Viktor's youth coincided with the “Khrushchev Thaw.” A lot of literature was published that at least slightly lifted the curtain on the shameful past. What could not be printed in the official press spilled into “samvydav,” was broadcast on Radio Liberty, to which the thinking intelligentsia, especially the youth, listened intently. The arrests of the Sixtiers in 1965 were happening before their eyes. The boys also wanted to act. For a start, Heorhiy suggested hanging a Ukrainian flag somewhere in Kyiv. They began to think about how and where to do it. They wanted to do it over the train station, but you wouldn't have time to get down before they caught you. They looked at the KINE building: there was a fire escape...

They found the blue fabric faster, but they had to search for the yellow one until they bought a woman's scarf in a shop on Harmatna Street (the Soviet authorities carefully ensured that goods of “nationalist colors” were not for sale). They sewed the flag in their room when their third roommate was not there. They copied the coat of arms from a 50 karbovanets banknote of the UNR. Although they knew it should be gold, it had to be visible from a distance. So they cut the trident out of black material – sateen.

On the night of May 1, they took the last tram, which then ran along Brest-Lytovsky Prospekt, from Sviatoshyn to the “Bolshevik” factory. Just in case, they got off at the previous stop, Harmatna. They were wary of late-night passers-by: each of the things they had with them could arouse suspicion. Heorhiy was supposed to climb onto the roof, but Viktor said he didn't know how to shoot his homemade pistol. He pulled socks over his shoes, put on gloves, tucked the kitchen knife into his pocket, and stuffed the flag inside his shirt. The roof turned out to be steeper than it seemed from below. He clung to the seams. Reaching the red banner, he caught it with the knife from below – and it rolled down the roof. He felt a thrilling joy. He tied his flag with a bandage – and it swayed in the light wind...

Heorhiy didn't have to shoot below: everything was calm. They poured gasoline around the ladder. As they left, they watched how beautifully and majestically the banner fluttered, illuminated from below by the May Day searchlights. They threw the bottle and the rest of the bandage into the lake in Komsomolsky Park.

In the morning, the boys went to see the results of their work – the flag was already gone. Then they went to Pushkin Park and took a photo to commemorate this most important event in their lives.

It was not difficult to “calculate” the daredevils. After all, they spoke Ukrainian everywhere, and Moskalenko could even say at a seminar that Lenin recognized the independence of Finland and Ukraine in one day. The West defended Finland, but the Bolsheviks occupied Ukraine. So why not now put the question of Ukraine's independence to a vote? The system could have remained socialist, but we would have been like Poland, like Czechoslovakia. Such statements were noted, as there were informants in every group. To be sure, they even moved one into their dormitory room. A notebook with addresses and phone numbers disappeared, and it contained the names of several “Sixtiers.” A graphological examination also pointed to Moskalenko. The circle narrowed. The boys still believe that the KGB had been on their trail for a long time but were not certain. Or they were looking for “connections” with foreign countries or with the underground that had “instructed” them.

They were arrested simultaneously on February 21, 1967. Moskalenko was then working as a master plumber in Fastiv. They sent a car for him and brought him to a construction organization in Kyiv, and there, three operatives put him in a “bobby” van – and to Rozy Luxemburg Street (now Lypska), to the regional KGB administration.

Viktor Kuksa was also summoned to the personnel department, two burly guys took him by the arms, put him in a “Volga” – and to 33 Volodymyrska Street, to the republican KGB.

The boys did not resist for long, because there was no point. The investigation was not complicated. The case was handled by Loginov, Chunikhin, Razumny, and the head of the investigative department, Lieutenant Colonel Dubovyk. Of course, in Russian: “So what are you – a fly! And here is an elephant. The elephant goes hop – and crushes you. See, you're gone.”

The investigators returned from vacation tanned: “Oh, boys, you're still here? Let's write a little more. About this homemade gun and the knife. We're not interested in that, it's a matter for the police, but let it be.” They added the knife and the homemade gun. They showed a photograph of the flag, which they packed in an envelope and wrote: “To be kept forever.” It must still be stored somewhere with the case file: this is what should be displayed in museums!

The closed trial lasted for three days. Two retired men, presented as witnesses, accused them more than the prosecutor. Only one witness testified that the boys had agitated him “in the spirit of nationalism.” On May 31, Heorhiy Moskalenko, as the initiator and for manufacturing a “firearm,” was sentenced to 3 years, and Viktor Kuksa to 2.

After the trial, they were transported together to Mordovia. On July 18, they were brought to Kharkiv. So many prisoners were crammed into the Black Maria van that some fainted. On the infamous Kholodna Hora, after “sanitary processing,” they were thrown into a death row cell: bunks made of sheet metal, triple bars on the windows, triple doors, metal pedestals instead of a table and chairs. But this did not make a special impression on the boys: they thought it was supposed to be this way. They even joked about how carefully they were being guarded. Mykhailo Osadchy, who was being returned to Ukraine on a transport, explained their situation to them. Here, they were finally shaved and, under convoy with dogs, led to the van. A whisper went through the criminal prisoners: “Who are they bringing?” – “English spies.” They were transported in a “troinik” [a three-person compartment] of a “Stolypin car” to Ruzayevka in Mordovia, then to Potma. Bedbugs ate Kuksa, but they didn't touch Moskalenko – different blood type.

Finally, Yavas, Zone 11. For the first time in several months, they saw green grass... But the very first impression was surprise: why, this is Ukraine! Out of a “contingent” of 800 prisoners, about 75% were Ukrainians! The dominant language was Ukrainian. “Whoever has not been in that camp,” says Viktor Kuksa, “does not know the real Ukraine.” All regions are represented here; here you can find out what kind of people live in all the oblasts. And they are all united by one national idea. Here is a complete international: strong communities of Lithuanians, Estonians, Latvians – our closest allies. They understand Ukrainian, and it is not surprising to hear from the lips of, say, an Estonian: “Man, what are you saying?” Here are Russian neo-Marxists and great-power chauvinists, and Russian democrats – mostly Jews. But still... The same was testified to by Mykhailo Masyutko in 1967:

“If some traveler, despite all the strict prohibitions, managed to visit the political prisoner camps of Mordovia, of which there are as many as six, he would be extremely surprised: here, thousands of kilometers from Ukraine, at every step he would hear distinct Ukrainian speech in all the dialects of modern Ukraine. The traveler would involuntarily ask: what is happening in Ukraine? Unrest? An uprising? What explains such a high percentage of Ukrainians among political prisoners, reaching up to 60, and even 70 percent? If such a traveler were to visit Ukraine soon after, he would immediately be convinced that there is no uprising, no unrest in Ukraine. But then a new question would arise for him: why is Ukrainian so rarely heard in the cities of Ukraine and why is it heard so often in the political prisoner camps?” (Cited from: *The Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords*: In 4 vols. Vol. 2. Documents and Materials... November 9, 1976 – July 2, 1977 / Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; Compiled by V.V. Ovsienko; Art design by B.F. Bublyk – Kharkiv: Folio, 2001. P. 37).

So, our boys were surrounded, asked questions. They brewed tea, passed a quart mug around, for everyone – a “long-lasting” candy to suck on... But no one asks about the case – it's not customary. Only later did the guards blab: “Ah, the standard-bearers!”

The insurgents serving 25-year sentences, such as Vasyl Yakubiak, Stepan Mamchur, Vasyl Pidhorodetsky, Levko Levkovych, Dmytro Basarab – were the most respected people in the zone. Moskalenko recalls that in three years, he did not hear a single swear word in the zone. Only “Pan” [Sir] – for both the older and the younger. It was the Banderites who established such rules back in the days of the uprisings of the late 40s and early 50s, when they achieved separation from the criminals. Here, they celebrate Christian and national holidays, honor the heroes of Kruty, of Bazar. Despite the fact that a prisoner's food costs only 43 kopecks a day, a high intellectual atmosphere reigns here: they order literature through “Book-by-Mail” and have assembled a good library. Everyone is familiar with the history of Ukraine, and a living one at that. Here they will tell you about the creation and battles of the UPA, about the heroic underground. They will tell you how to set up a kryivka [bunker]. The insurgents were very happy when, in 1966, fresh blood poured into the camps – a brilliant cohort of the Sixtiers: Ivan Hel, Sashko Martynenko, Bohdan Horyn, Mykhailo Horyn, Mykhailo Osadchy, Mykhailo Ozerny, Bohdan Rebryk, Opanas Zalyvakha... So, Ukraine has not yet perished, since it sends new and new Cossacks to this new Zaporozhian Sich!

Opanas Zalyvakha is not allowed to paint, so he carves something out of wood. On a flowerbed, he has grown a portrait of Shevchenko with flowers.

This camp was settled by the Japanese after the war, from whom gazebos, alleys, and sports grounds, where the younger ones play basketball, have been preserved. In the evening, a brass band plays, or the Ukrainians sing folk songs – the Mordvins outside the zone come out to listen. And when they learn riflemen's songs or the anthem, the guards disperse them. They have to hide behind the barracks.

This was, so to speak, the “golden age” of the political zones – just a few years later, when I arrived in Mordovia, the regime had become much stricter.

Heorhiy Moskalenko, in the 11th and then in the 19th zone, worked as a plumber, and Viktor Kuksa mastered a bulldozer, which was even used for unloading lime. Digging in the zone was not allowed – bones everywhere... You could hear the guard change: “Comrade Sergeant, Post No. 3 for the protection of state criminals and traitors to the Motherland is relieved!”

While still under investigation, General Tikhonov came to look at the “especially dangerous state criminals.” Moskalenko then compared his act with the actions of the Krasnodon “Young Guards.” “But that was for the Motherland, for an idea!” said the general, for whom Ukraine was no “motherland.” Well, in Yavas, there was a man named Stetsenko, the burgomaster of Krasnodon during the German occupation. The boys did not get to talk to him, but Viktor Kuksa spoke with his coachman, Stepan Davydenko, on several occasions and recounts the following:

“Davydenko was Oleg Koshevoy's stepfather. One day Stetsenko ordered: ‘Tomorrow, harness the horses. We're going, the Germans want to arrest Tyulenin and someone else there.’ In the evening, Davydenko warned Tyulenin: ‘Run, Serhiy, because they will arrest you tomorrow.’ But they were young boys, they didn't listen, and they were caught. And they were supposedly caught because they stole Christmas presents that had arrived for German soldiers from unguarded trucks. They gave chocolate to a boy, Ivan Zemnukhov's brother. He went out into the street with that chocolate, and a patrol was passing by, saw it, and from this chocolate the Germans got on the trail of the young thieves. The Germans punished theft mercilessly – they threw them into a mine shaft. As for whether that ‘Young Guard’ existed – I cannot say. It was only after the war that they made a symbol of resistance to the occupiers out of thieves. When I spoke with him, Davydenko was already about 60, Stetsenko about 70. It's certain they never returned to Krasnodon and never told the truth.”

I will add that the OUN underground member Yevhen Stakhiv, whom Aleksandr Fadeyev tried to portray in the novel “The Young Guard” as the policeman Stakhovych, wrote that he learned about young people who were writing down the markings on German military vehicles and realized that this was some kind of intelligence. “We wanted to involve these young people – they were 17-18 years old – in cooperation, but it turned out that they did not understand any politics. They were simply collecting data for the intelligence agent Lyubov Shevtsova. Later we learned from Aleksandr Fadeyev many exaggerations, untruths about their activities. So, we broke off all contact with them to avoid possible trouble from the German counterintelligence or the Gestapo.” (Yevhen Stakhiv. *Through Prisons, the Underground, and Borders*. Kyiv: Rada, 1995, pp. 135-136).

Our President recently ordered the myth of the Young Guards to be revived to educate the youth. And Moskalenko and Kuksa – let them continue to be criminals.

...When Viktor Kuksa returned to his native village after two years, he found his father in an unburied grave – they left him so his son could see him. With difficulty, he got a job in Kyiv as an excavator operator and in the same dormitory. Summonses to the KGB, checks by the district policeman... When heads of foreign states came to Kyiv, he was sent on a business trip somewhere. But despite this, he again communicated with the Sixtiers Ivan Svitlychny, Ivan Rusyn, and with Vasyl Stus, who lived nearby, at 62 Lvivska Street. In the pogrom year of 1972, he was subjected to searches. He often had to change jobs. Only after the declaration of independence was he left alone. Since then, he has been working at the Ukrainian Oil and Gas Institute. In 1973, he married a girl of his views, Mariya Polishchuk; they have a 10-year-old boy, Vladyslav, and live in Borshchahivka.

Heorhiy Moskalenko was hired as a 3rd-grade worker, but soon he became a foreman, a master, a construction manager, and received an apartment in Bucha. He has three sons with his wife Vira. He never finished his fifth year at KINE, although he had already written his diploma thesis before his arrest. They offered him to become an informant. He thanked them and said: “I cannot be a snitch on my comrades.” – “Well, in that case, you won't get a diploma.” They issued him an academic transcript.

In conclusion, Viktor Kuksa told me: “Once I went to my mother in the village, and my mother said: ‘Son, chop some firewood.’ I took an axe and started chopping. I raised the axe, wanted to split a log – and then I saw: old Ligor was standing at the gate and looking at me. I lowered the axe. The old man took off his hat and bowed low, very low to me. And then he asks: ‘Are you Ivan's son?’ – ‘Ivan's.’ – ‘He was a good man, may he rest in peace. But you are a good boy too. I know everything.’ And he left. And I stood there for a few more minutes...”

When will our state begin to recognize its best citizens?

*Shlyakh peremohy*. – 2002. – No. 20 (2507). – May 16; *Ekonomist* (KNEU). – 2002. - No. 16 – 19 (1054 – 1057). – June – July.

Vasyl Ovsienko. *The Light of People: Memoirs and Publicism*. In 2 vols. Vol. 2 / Compiled by the author; Art design by B.Y. Zakharov. – 2nd edition, supplemented. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2005. – 352 pp., photo illus. – Pp. 90-98.

DECREE OF THE PRESIDENT OF UKRAINE № 693/2006

On awarding the Order “For Courage”

For civic courage shown in raising the national flag of Ukraine in the city of Kyiv in 1966 and the city of Chortkiv, Ternopil Oblast in 1973, and for active participation in the national liberation movement, I hereby decree:

To award the Order “For Courage,” I degree, to

VITIV, Petro Ivanovych – a builder at the agricultural enterprise “Rosokhatske,” Ternopil Oblast

VYNNYCHUK, Petro Mykolayovych – a builder at the agricultural enterprise “Rosokhatske,” Ternopil Oblast

KRAVETS, Andriy Mykolayovych (posthumously) – a former resident of the village of Rosokhach, Ternopil Oblast

KUKSA, Viktor Ivanovych – an engineer at the joint-stock company “Ukrainian Oil and Gas Institute,” city of Kyiv

LYSYI, Mykola Stepanovych – a pensioner, village of Rosokhach, Ternopil Oblast

MARMUS, Mykola Vasylyovych – a pensioner, village of Rosokhach, Ternopil Oblast

MARMUS, Volodymyr Vasylyovych – head of a sector of the Chortkiv Raion State Administration, Ternopil Oblast

MOSKALENKO, Heorhiy Mytrofanovych – a pensioner, town of Bucha, Kyiv Oblast

SENKIV, Volodymyr Yosafatovych – a machine operator at the collective peasant enterprise “Sosulivske,” Ternopil Oblast

SLOBODIAN, Mykola Vasylyovych – a pensioner, village of Rosokhach, Ternopil Oblast.

President of Ukraine Viktor YUSHCHENKO

August 18, 2006

SUPREME COURT OF UKRAINE

RULING

IN THE NAME OF UKRAINE

The Supreme Court of Ukraine, at a joint session of the Judicial Chamber for Criminal Cases and the Military Judicial Collegium, under the chairmanship of the First Deputy Head of the Supreme Court of Ukraine, with the participation of the Deputy Prosecutor General of Ukraine P.P. Pylypchuk, V.V. Kudryavtsev, considered in the city of Kyiv on January 26, 2007, the petition of the Deputy Prosecutor General of Ukraine, submitted for consideration upon the proposal of the judges of the Supreme Court of Ukraine, for a review under the exclusive proceedings procedure of the judicial decisions concerning Moskalenko, H.M. and Kuksa, V.I.

By the verdict of the Kyiv Oblast Court of May 31, 1967, the following were sentenced:

MOSKALENKO, Heorhiy Mytrofanovych, born July 24, 1938, a native of the city of Odesa, with no prior convictions, –

- under Part 1 of Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 3 years of deprivation of liberty;

- under Part 1 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 2 years of deprivation of liberty;

- under Part 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR (in the version that was in effect before the amendments to this article were made

by the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the UkrSSR of October 14, 1974) to 1 year of deprivation of

liberty;

on the basis of Art. 42 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, by the totality of crimes, a sentence of three years of deprivation of liberty was determined;

KUKSA, Viktor Ivanovych, born February 13, 1940, a native of the village of Savarka, Bohuslavskyi Raion, Kyiv Oblast, with no prior convictions, –

- under Part 1 of Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 2 years of deprivation of liberty;

- under Part 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR (in the version that was in effect before the amendments to this article were made

by the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the UkrSSR of October 14, 1974) to 1 year of

deprivation of liberty;

on the basis of Art. 42 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, by the totality of crimes, a sentence of two years of deprivation of liberty was determined.

By the ruling of the Judicial Collegium for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR of July 4, 1967, the verdict concerning Moskalenko, H.M. and Kuksa, V.I. was left unchanged.

Moskalenko, H.M. and Kuksa, V.I. were found guilty of committing the following crimes.

Moskalenko, H.M. took part in the illegal manufacture of a firearm – a homemade pistol, which he illegally possessed and carried. He also illegally manufactured a cold weapon – a Finnish-type knife.

On the night of May 1, 1966, Moskalenko, H.M. and Kuksa, V.I., being nationalistically minded, tore down the Soviet flag from the roof of the Kyiv Institute of National Economy and replaced it with a yellow-and-blue flag. In doing so, they were armed (i.e., illegally carrying): Moskalenko, H.M – with a pistol, and Kuksa, V.I. – with the knife manufactured by Moskalenko, H.M.

By the resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of Ukraine of May 20, 1994, the court decisions regarding the conviction of Moskalenko, H.M. and Kuksa, V.I. under Part 1 of Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR were overturned, and the case was closed on the basis of clause 2 of Art. 6 of the CPC of Ukraine due to the absence of corpus delicti in their actions. By the totality of crimes provided for by Part 1 and Part 3 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, it was resolved to consider Moskalenko, H.M. sentenced to two years of deprivation of liberty, and Kuksa, V.I. – under Part 3 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine to one year of deprivation of liberty.

In the petition of the Deputy Prosecutor General of Ukraine, submitted for consideration at a joint session upon the proposal of the judges of the Supreme Court of Ukraine, the question is raised of overturning the court decisions regarding the conviction of Moskalenko, H.M. and Kuksa, V.I. under Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine due to the absence of corpus delicti.

Having heard the rapporteur and the prosecutor, who requested that the petition be granted, having reviewed the case materials and discussed the arguments of the petition, the judges of the Supreme Court of Ukraine consider that it should be granted.

From the subjective side, the crimes provided for by Parts 1 and 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR (in the version that was in effect before the amendments to this article by the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the UkrSSR of October 14, 1974) are characterized by direct intent. It follows from this that Moskalenko, H.M.'s liability for committing these crimes could arise only if, when making the pistol and knife, he intended to create specifically a firearm and a cold weapon, and when carrying and possessing the pistol, he was aware that he was committing these acts with a firearm. Accordingly, Kuksa, V.I.'s liability could arise only if, when carrying the knife, he was aware that he was committing this act with a cold weapon.

In accordance with the requirements of Articles 323 and 334 of the CPC of the UkrSSR, all conclusions of the court, including those concerning the content of the subjective side of the act, had to be substantiated, and the verdict had to state the evidence on which these conclusions are based. From the case, however, it is apparent that neither the preliminary investigation bodies nor the court, contrary to the requirements of criminal and criminal procedure law, paid any attention to the issue of the content of the subjective side of the acts committed by Moskalenko, H.M. and Kuksa, V.I.

As seen from the case materials, Moskalenko, H.M., while not denying the fact that he made the pistol and the knife, explained that he made the homemade pistol not for use as a weapon, but “out of mischief,” and was not aware that the pistol and knife were, respectively, a firearm and a cold weapon; that many people had access to these items, and the knife was used exclusively for household purposes. Both convicts explained that they took the knife with them to whittle the flagpole, and the homemade pistol to frighten anyone who would interfere with raising the flag. These explanations of theirs, contrary to the requirements of Art. 334 of the CPC of the UkrSSR, remained unrefuted.

The liability of Moskalenko, H.M. and Kuksa, V.I. for committing the said crimes could also arise only if the pistol and the knife were indeed, respectively, a firearm and a cold weapon.

From the case, it is apparent that the court based its conclusions in this part exclusively on the findings of a criminalistic examination, which established that the knife is a cold weapon, and the findings of a forensic chemical and ballistic examination, according to which the pistol is a firearm.

In giving such evidentiary value to the findings of these examinations, the court, in accordance with the requirements of Art. 75 of the CPC of the UkrSSR, needed to carefully verify whether they were substantiated. However, this was not done; the court limited itself to merely announcing the findings of the examinations, without delving into the question of their substantiation.

Meanwhile, from the findings of the criminalistic examination (vol. 2, p. 259), it is apparent that the expert did not investigate the characteristics of the steel from which the knife was made (while Moskalenko, H.M. claimed that the knife blade had not undergone heat treatment), the suitability of the knife for inflicting stabbing blows, the functional purpose of the guard, and no assessment was given to the fact that the knife significantly differs from Finnish knives.

From the findings of the forensic ballistic examination (vol. 2, pp. 315-317), it is apparent that the expert, contrary to the then-current “Methodology for establishing the attribution of an object to a firearm,” did not investigate the striking power of the homemade pistol, although the study of this particular characteristic is one of the mandatory requirements for resolving the issue of classifying an object as a firearm.

The findings of the forensic chemical examination, contrary to the court’s assertion, do not state at all that the pistol is a firearm.

It is worth noting that according to the findings No. 5530 and No. 5531 of July 14, 2006, of a commission of specialists from the Kyiv Scientific Research Institute of Forensic Expertise, the physical evidence in the case – the knife – by its design features is a household item and does not classify as a cold weapon, and the attribution of the homemade pistol (self-made gun) to a firearm cannot be established, as significant violations of the requirements of the “Methodology for establishing the attribution of an object to a firearm and its suitability for shooting,” which was in effect at the time of the investigation, were committed during the examination of this object.

Under such circumstances, it should be concluded that the court of first instance, when considering the case, incorrectly applied the criminal law and significantly violated the requirements of the criminal procedure law, and the court of cassation did not pay attention to the violations committed. In this regard, bearing in mind that all doubts about the proof of a person's guilt in committing a crime should be interpreted in their favor, the verdict of the Kyiv Oblast Court of May 31, 1967, and the ruling of the Judicial Collegium for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR of July 4, 1967, concerning the conviction of Moskalenko, H.M. under Parts 1 and 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR and Kuksa, V.I. under Part 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR should be overturned, and the case in this part should be closed on the basis of clause 2, Part 1 of Art. 6 of the CPC of Ukraine.

Since the Plenum of the Supreme Court of Ukraine on May 20, 1994, actually considered the case within the limits of a protest, which raised the issue of overturning the court decisions only in the part of the conviction of Moskalenko, H.M. and Kuksa, V.I. under Part 1 of Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, the penultimate paragraph should be excluded from the reasoning part of the Plenum's resolution, and from the operative part – the indication that by the totality of crimes,

provided for by Part 1 and Part 3 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, Moskalenko, H.M. is to be considered sentenced to two years of deprivation of liberty, and Kuksa, V.I. – under Part 3 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine to one year of deprivation of liberty.

Guided by Articles 400, 4001 of the CPC of Ukraine, the Supreme Court of Ukraine

has ruled:

To grant the petition of the Deputy Prosecutor General of Ukraine.

To overturn the verdict of the Kyiv Oblast Court of May 31, 1967, and the ruling of the Judicial Collegium for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR of July 4, 1967, in the part of the conviction of Moskalenko, H.M. under Parts 1 and 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR and in the part of the conviction of Kuksa, V.I. under Part 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, and to close the case in this part due to the absence of corpus delicti in their actions on the basis of clause 2, Part 1 of Art. 6 of the CPC of Ukraine.

To exclude from the resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of Ukraine of May 20, 1994: from the reasoning part, the penultimate paragraph; from the operative part, the indication that by the totality of crimes provided for by Part 1 and Part 3 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, Moskalenko, H.M. is to be considered sentenced to two years of deprivation of liberty, and Kuksa, V.I. – under Part 3 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine to one year of deprivation of liberty.

Presiding Judge P.P. Pylypchuk

Rapporteur Judge S.D. Peknyi

SUPREME COURT OF UKRAINE

01024, Kyiv-24, 4 P. Orlyka St.

….. March 2007 No. 5-47p06

Certificate of Rehabilitation

By the verdict of the Kyiv Oblast Court of May 31, 1967, Moskalenko, Heorhiy Mytrofanovych, born 1938, a native of the city of Odesa, was convicted under Part 1 of Art. 62, Parts 1, 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR (of 1960 in the version that was in effect before the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the UkrSSR of October 14, 1974, which introduced amendments and liability for the illegal handling of cold weapons became provided for by Part 3 of this article) to 3 years of deprivation of liberty on charges of illegal manufacture, possession, and carrying of firearms and cold weapons, as well as for, being nationalistically minded, together with Kuksa, V.I., tearing down the Soviet flag from the roof of the Kyiv Institute of National Economy and replacing it with a yellow-and-blue flag.

By the ruling of the Judicial Collegium for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR of July 4, 1967, the verdict was left unchanged.

By the resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of Ukraine of May 20, 1994, the court decisions regarding the conviction of Moskalenko, H.M. under Part 1 of Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR were overturned, and the case was closed on the basis of clause 2 of Art. 6 of the CPC of Ukraine due to the absence of corpus delicti in his actions. By the totality of crimes provided for by Part 1 and Part 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, it was resolved to consider Moskalenko, H.M. sentenced to 2 years of deprivation of liberty.

By the ruling of a joint session of the Judicial Chamber for Criminal Cases and the Military Judicial Collegium of the Supreme Court of Ukraine of January 26, 2007, the verdict of the Kyiv Oblast Court of May 31, 1967, and the ruling of the Judicial Collegium for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR of July 4, 1967, in the part of the conviction of Moskalenko, H.M. under Parts 1, 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR were overturned, and the case in this part was closed due to the absence of corpus delicti in his actions on the basis of clause 2, Part 1 of Art. 6 of the CPC of Ukraine.

Moskalenko, Heorhiy Mytrofanovych, has been rehabilitated in this case.

Acting Head of the Judicial Chamber for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of Ukraine

M.Ye. Korotkevych

SUPREME COURT OF UKRAINE

01024, Kyiv-24, 4 P. Orlyka St.

…..March 2007, No. 5-47pО6

Certificate of Rehabilitation

By the verdict of the Kyiv Oblast Court of May 31, 1967, Kuksa, Viktor Ivanovych, born 1940, a native of the village of Savarka, Bohuslavskyi Raion, Kyiv Oblast, was convicted under Part 1 of Art. 62, Part 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR (of 1960 in the version that was in effect before the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the UkrSSR of October 14, 1974, which introduced amendments and liability for the illegal handling of cold weapons became provided for by Part 3 of this article) to 2 years of deprivation of liberty on the charge that, being nationalistically minded, together with Moskalenko, H.M., he tore down the Soviet flag from the roof of the Kyiv Institute of National Economy and replaced it with a yellow-and-blue flag. In doing so, Kuksa, V.I. was armed with a knife.

By the ruling of the Judicial Collegium for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR of July 4, 1967, the verdict of the Kyiv Oblast Court of May 31, 1967, concerning Kuksa, V.I. was left unchanged.

By the resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of Ukraine of May 20, 1994, the court decisions regarding the conviction of Kuksa, V.I. under Part 1 of Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR were overturned, and the case was closed on the basis of clause 2 of Art. 6 of the CPC of Ukraine due to the absence of corpus delicti in his actions. It was resolved to consider Kuksa, V.I. sentenced under Part 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 1 year of deprivation of liberty.

By the ruling of a joint session of the Judicial Chamber for Criminal Cases and the Military Judicial Collegium of the Supreme Court of Ukraine of January 26, 2007, the verdict of the Kyiv Oblast Court of May 31, 1967, and the ruling of the Judicial Collegium for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR of July 4, 1967, in the part of the conviction of Kuksa, V.I. under Part 2 of Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR were overturned, and the case in this part was closed due to the absence of corpus delicti in his actions on the basis of clause 2, Part 1 of Art. 6 of the CPC of Ukraine.

Kuksa, Viktor Ivanovych, has been rehabilitated in this case.

Acting Head of the Judicial Chamber for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of Ukraine

M.Ye. Korotkevych