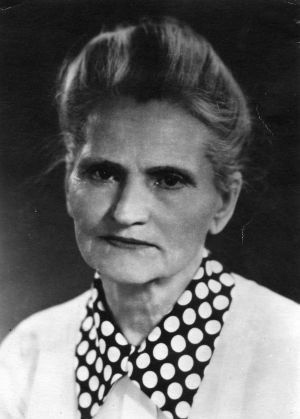

A COSSACK MOTHER (Oksana Meshko)

Oksana Yakivna Meshko, who left us on January 2, 1991, in the 86th year of her life, was one of the most luminous personalities of our time. This woman staged a breathtaking resistance to an entire Evil Empire, initially out of a need for self-preservation, and later emerged as an organizer of a determined struggle for human and national rights, known in our history as the Helsinki movement. She became one of the most outstanding figures of the Ukrainian national liberation movement of the 1960s–80s.

The fate of her family is indicative of the destruction of the Ukrainian identity by the occupying Russian power, which called itself Soviet. Oksana was born on January 30, 1905, in the small town of Stari Sanzhary on the Vorskla River in the Poltava region, into a family of land-poor farmers of Cossack descent that had avoided serfdom and thus preserved its unvanquished spirit. The girl had barely turned fifteen when the bloody reckonings with the Bolshevik authorities, brought to Ukraine on Russian bayonets, began for her. “In the spring of 1920, a Red military detachment,” Oksana Meshko recounts in her memoirs “Between Death and Life” (pp. 3–4), “was rounding people up in the volost for a gathering. They took hostages as punishment for failing to meet the prodpodatok [food tax]. My forty-year-old father, Yakiv Meshko, was among the hostages, for reasons unknown: whether he was the tenth in line, or standing nearby, or whether an assailant simply set his eyes on him, for he owed nothing to the volost. The arrested were herded to the Gubernia Cheka… They shot my father in Kharkiv, on Kholodna Hora, in December 1920 (as was stated in the certificate). After my father’s arrest, persecution of our family and relatives by the local soviet authorities began—illegal requisitions of food, livestock, farming equipment…” Soon, her 17-year-old brother Yevhen, a member of “Prosvita” and the director of its drama club, died at the hands of an activist-bandit. “Hunted and persecuted, the fragments of our family—two sisters, Vira and Kateryna, and brother Ivan—scattered across the world, wherever they could go.” (Ibid., p. 4).

In 1927, Oksana Meshko enrolled in the chemistry department of the Institute of Public Education in Dnipropetrovsk and managed to graduate in 1931 despite being expelled several times “for social origin.” Clenching her fists, she fought time and again to be reinstated, as she was not from the “exploiter” class. She prepared for exams as an external student, with neither a scholarship nor a dormitory, but she never joined the Komsomol.

During her studies, Oksana Meshko married an institute instructor, Fedir Serhienko, a former member of the Ukrainian Communist Party, which was almost entirely imprisoned in 1925 on Kholodna Hora in Kharkiv—Fedir among them. The leaders of the UCP, which was seen as a “fellow-traveling” party to the CP(b)U, never left that place, but the rank-and-file “Borotbists” were released, only to be annihilated later. Oksana was not destined to know family happiness: “My two sons, Yevhen and Oleksandr, born in 1930 and 1932, I raised in the grim times of the artificial famine in Ukraine on ration cards, in the suffocating atmosphere of Stalinist lawlessness, fear, and general suppression in the country’s civic and social life.”

In early 1935, Fedir Serhienko was arrested again. “His second arrest was as unexpected as it was baseless,” writes O. Meshko (Ibid., p. 5).

For almost a year, his wife had to knock on the doors of various institutions. She even reached the republic’s prosecutor general. The case was eventually returned for further investigation, and after 9 months, Fedir Serhienko was released from prison. But, although free, her husband had to leave Ukraine altogether. Once released, he could not find work in Dnipropetrovsk. He went to the Urals. With her two sons and her mother, Mariya, she had to endure hardship alone.

In 1936, Oksana’s uncle, Oleksandr Yanko, a former member of the Central Rada and an official of the Directorate, a member of the Kyiv Union of Political Prisoners, was arrested, like almost all its members, “for loss of vigilance.” During interrogations, he, “a man of mighty spirit and body, was tortured, his teeth knocked out, then taken to an unknown location without the right to correspond” (Ibid., p. 6). According to his rehabilitation certificate, he died a free man in 1946.

In 1937, her cousin, Yevhen Meshko, was executed for “agitation” during his military service. At the same time, Oksana’s second uncle, Dmytro Yanko, a disabled worker, was arrested in Kharkiv (his subsequent fate is unknown).

As a relative of so many “enemies of the people,” she could not remain in a Soviet institution; in 1937, she was dismissed from the Institute of Grain Farming, where she worked in the chemical laboratory, due to “downsizing.” Oksana took her elder son Yevhen and went to Tambov, where her husband had already settled. Later, she brought her younger son, Oles, there as well. She thought she could retreat into her family circle. It was there that the war found the family, immediately taking her 11-year-old firstborn, who was killed during a German bombing raid. Soon, her husband was mobilized into the active army. With little Oles, Oksana Meshko found herself in the tumultuous ocean of humanity churned by the war…

In May 1944, Oksana Yakivna returned with her son Oles to Dnipropetrovsk and found only her mother, Mariya, there. Her husband returned from the war as a disabled veteran. While the cannons of World War II were still thundering on German soil, the Meshko-Serhienko family gathered in Kyiv. Her older sister, Vira Khudenko, also made her way there from the Rivne region in the autumn of 1946. The war had taken her sister’s two adult sons, her daughter-in-law, and her husband. Her elder son Vasyl, a student before the war, had been a German prisoner, escaped, and died in the ranks of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. Neighbor-informants called in the NKVD agents: one day, Vira disappeared—she went out into the street and never returned. Oksana rushed to find her. For nearly half a month, she went from hospitals to morgues, police stations, and prosecutor’s offices, until she found Vira’s trail: “My concern for my sister, an elementary human attitude toward a person in trouble, decided the tragic course of my fate, the fate of my 13-and-a-half-year-old son, and my defenseless elderly mother,” Oksana Yakivna would write in her later years. “On February 19, 1947, on Lvivska Square in broad daylight, three men in white sheepskin coats forced me into a car and took me to the KGB’s internal prison at 33 Korolenko Street. They presented a warrant for my arrest and after a humiliating ‘personal’ search, they shoved me into a box, the size of a wardrobe but taller, dark, with a small closed window at the top and a tiny electric bulb. Then came the first interrogation, then a prison cell, a dark, damp solitary confinement.” (Ibid., p. 8).

Oksana Meshko was accused of intending, together with her sister Vira, to assassinate the first secretary of the CC of the CP(b)U, Nikita Khrushchev. However, she persistently denied this. “I did not confess even after 21 days of interrogation without sleep, which was carried out as follows: night interrogations began 30–40 minutes after ‘lights out,’ and ended an hour, sometimes less, before ‘reveille’… During the day, a ‘peephole’ guard made sure I stayed awake and did not doze off. One could sit on the bunk, but not lie down. For ‘nodding off,’ they would put you in a punishment cell in a cold basement and take away your warm outer clothing. The cell had no bed or ‘mattress,’ the ration was 300g of bread and hot water twice. Sometimes for dozing, they put you in the box, where the air quickly ran out, and I would lose consciousness…” (Ibid., p. 8).

Despite all the torture, Oksana Meshko did not break and did not sign the “sincere confessions” scribbled by the investigator: “I remained steadfast, preparing myself for the worst, just so I would not testify to what they had been demanding from me for so long. Together, my sister and I were about 90 years old, a rather respectable age to end our tribulations on this sinful earth, but it had to be done with honor and dignity” (Ibid., p. 10).

Seven months later, in the Lukyanivska Prison, the sisters were read the verdict in absentia from the OSO of the USSR MGB: 10 years in corrective labor camps.

At the price of a seven-day hunger strike, Oksana Yakivna managed to secure a meeting with her son and mother, to which she was legally entitled. “Through two wire meshes, our eyes locked onto one another. Trying to be calm, I entrusted my son to the careful hands of my poor mother—a sick old woman. Mama held up bravely. To my son Oles’s repeated question of how long my sentence was, I answered only at the very end of the visit. Oles drew out his words: ‘Ten years,’ and then suddenly began to cry loudly; Mama tore at the door of the booth that was our barrier, I threw open my door, and in a tight struggle, the three of us embraced in despair and tears. A trapped guard barely managed to push me away, and Mama went out with her grandson on her own, stumbling, stooped…” (Ibid., pp. 10-11).

Without accepting any warm clothes from her mother, the 42-year-old woman was sent in a transport, in the clothes she was wearing, to Ukhta in the Komi Republic. Oksana Yakivna recounted her tribulations in the hell of the Gulag in an autobiographical essay written in the 1970s, “Between Death and Life.” This touching human document and, at the same time, a document of an era, which reflects the fate of an entire nation, is read with a lump in one’s throat. It is a truthful view of a Ukrainian woman on a monstrous world created by a foreign spirit, by a violent ideology hostile to man. It is a pity that O. Meshko’s memoirs remain virtually unknown among our people—published by NVP “YAVA” in 1991 in a semi-samizdat manner, with a small print run, the book quickly became a bibliographic rarity, almost inaccessible to the general public. We should note that this book was previously published in English: Between Death and Life. By Oksana Meshko. Translated from Ukrainian by George Moshinsky. N.Y.–Toronto–London–Sydney: 1981. p. 171, and in the winter of 1978–79, it was read on Radio Liberty.

Here is what Oksana Yakivna writes about the agricultural zone in Ukhta: “We went to and from work as if dazed—so tired and hungry. The hunger was so gnawing that it was impossible to think of anything else” (Ibid., pp. 17-18). About the quarry, where she broke and loaded stone: “…We were freed from everything. There was no more sharp despair, no fear, no longing for our relatives, for our children. There was only hunger and there was fatigue and that slow state of transition into spiritual nonexistence through an all-consuming apathy” (Ibid., p. 22). “On a production ration with a diabolical calculation ‘to wear one down,’ with a maximum term of 3–5–10 years—the lifespan obviously calculated for a theoretical human ‘specimen’ as a biological unit—we were therefore always hungry, and thus exhausted and therefore weak and sick, we were supposed to work ‘to the grave, to the silent end.’ That’s exactly what our deadly circle looked like!—And no one dared to leave it until their last breath…” (Ibid., p. 43).

In 1954, a commission of the CC CPSU finally certified Oksana Yakivna as infirm: she was released from behind the barbed wire into exile. To return home, the consent of her relatives to support her was required. Her son Oles immediately sent such a document, but she received her passport only in 1956. In June, she made it to Kyiv in a padded jacket, where she bowed to the grave of her long-suffering mother at the Baikove Cemetery (she had died on November 13, 1951). In a tiny room of 4.5 square meters, her 24-year-old student son struggled with poverty and illness.

On July 11, 1956, Colonel of Justice Zakharchenko, handing Oksana Meshko her rehabilitation certificate, said with a note of sincerity: “The Motherland asks for your forgiveness. Do not remember the evil that was done to you. I wish you happiness and good health.” (Ibid., p. 57). Two years later, as a rehabilitated person, she was given a room of 12 square meters. After the death of Fedir Serhienko, mother and son began to live in the private family homestead in Kurenivka, at 16 Verbolozna Street, where they began to build a house.

A place in the sun came at a high price, and spiritual and moral connections were no easier to find. Khrushchev’s liberalization somewhat released the creative energy of a handful of the surviving intelligentsia of the older generation, but it also gave rise to a new generation—the Sixtiers, who, in the words of the poet Mykola Vinhranovsky, “grew from small, skinny mothers in a chopped-down garden.” The veil over the recent shameful past was timidly lifted. People gathered near the monuments to Shevchenko and Franko, for literary evenings that were not sanctioned by anyone, but, surprisingly, were not forbidden either. Oksana Yakivna organized dozens of them, each time in unexpected places: in factory clubs, houses of culture, schools. Once in 1969, she asked Yevhen Sverstiuk to write a script for an evening dedicated to Ivan Kotliarevsky for his 200th anniversary. Sverstiuk wrote an article, “Ivan Kotliarevsky is Laughing”: “I’m sorry, it’s not quite what you asked for…” “It’s exactly what’s needed.”

The hospitable doors of the private ethnographic museum of the great devotee of Ukrainian culture, Ivan Makarovych Honchar, opened. On the slopes of the Dnipro, the persecuted “Homin” choir, led by Leopold Yashchenko, held rehearsals. Here and there, “seditious” poems were published, and “samvydav” (samizdat) flourished.

The Sixtiers were not frightened by the arrests that began on August 25, 1965 (21 people were imprisoned then). On the contrary, letters in defense of the accused appeared. Ivan Dziuba’s fundamental polemical treatise “Internationalism or Russification?”, in the preparation of which Oksana Yakivna’s son, Oles Serhienko, was also involved, gained wide publicity.

Starting in 1964, a tradition was established to honor Taras Shevchenko on the day of his reburial in Kaniv on May 22, 1861. “On this day, a great number of people would gather in the park,” recalled Oksana Meshko. “Bouquet by bouquet, mountains of flowers would accumulate. On May 22, 1966, my son was also among the active admirers of Taras Shevchenko near the monument. From the monument’s pedestal, Oles Serhienko read the poet’s verses. However, this evening was different from the previous two years: under the crossfire of camera flashes, recording devices, a whole detachment of police and police ‘paddy wagons’ on the university square (opposite Shevchenko Park), and a large detachment (in civilian clothes) of the KGB’s ever-watchful eye and mobile radios (eavesdropping radio microphones) in the park’s bushes—nothing escaped the KGB’s attention, everything was documented.” (Ibid., p. 51). Several people, including Oles, were arrested for 15 days and subsequently expelled from the medical institute. He went to teach drawing and drafting in a school, but for his speech at the funeral of the murdered artist Alla Horska on December 8, 1970, he was dismissed from his job.

In the case of Valentyn Moroz, the first search of O. Meshko’s home was conducted on June 2, 1971. They seized everything that seemed suspicious. Oksana Yakivna protested in a letter to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet and the KGB.

Meanwhile, the threat of a new purge hung over the still-immature cluster of talented and spirited young Ukrainian intelligentsia.

At the end of 1971, a young man from Belgium named Yaroslav Dobosh, a member of the Ukrainian Youth Association, visited several prominent Sixtiers in Lviv and Kyiv. On his way back, he was detained at the border in Chop, and, as the newspapers then bashfully wrote, “one anti-Soviet document” was confiscated. It turned out to be a microfilm of a Dictionary of Ukrainian Rhymes. The Dictionary became “anti-Soviet” only because it was compiled by the political prisoner Sviatoslav Karavansky. But the pretext was found. On February 11, 1972, the newspapers “Vechirniy Kyiv,” “Radians’ka Ukraina,” and “Pravda Ukrainy” reported: “For conducting activities hostile to the socialist system and in connection with the Dobosh case, I.O. Svitlychny, V.M. Chornovil, Ye.O. Sverstiuk and others have been brought to criminal responsibility.” Yes, exactly, “Chornovil.” And behind the “and others” stood dozens of people, hundreds of searches, thousands of summons for interrogations, dismissals from work, expulsions from universities, removal from housing queues, “and others.” No one was incriminated with espionage, not even Dobosh himself, who, after repenting on television and in the press, was soon released, yet the aforementioned newspapers have still not apologized for the slander.

The purge began on January 12, 1972—Oles Serhienko was also caught in it.

On May 22, Oksana Yakivna walked through a desolate Kyiv with flowers to the Shevchenko monument. She was pushed into a car and taken to the KGB, where, under painfully familiar circumstances, she was interrogated in her son’s case.

Search after search, summons to the KGB, interrogations. And Oksana Yakivna’s persistent attempts to at least somehow alleviate the conditions of her son’s imprisonment, who was ill with pulmonary tuberculosis. This was no longer just a mother’s concern for her son—it was walking on a razor’s edge. Her statements, passionate and stylistically perfect, were evidence-based, because they were founded on knowledge of the laws, on iron logic, and a sense of her own rightness and moral superiority. They are brilliant examples of human rights commentary. This was no longer just the voice of a mother in defense of her son. This was now an open struggle for human rights—against the entire Evil Empire. Knowing from her own experience how people suffer in captivity, she tried to help everyone, even if only with a kind word. For the families of political prisoners, she sought not only kind words but also material assistance, especially when a package needed to be sent to a political prisoner or for a visit, and there was no money and nothing to bring.

It seemed that after 1972, in the empty, spiritually devastated Kyiv, there was not a single living soul left, unbroken, untainted by the filth of repentance or cruelty. (“This remnant of paradise, a temple that has known desecration…”—wrote V. Stus about Kyiv in 1975, when he was brought here as a prisoner to be “brainwashed” in the KGB).

And yet, in Ukraine, there were a few people whom descendants would later call the conscience of the nation. Because they testified before the world that the final nail had not yet been driven into Ukraine’s coffin. In the most difficult of times, Ukraine held on thanks to the obsessed:

Up the steep and flinty mountain

I shall carry a heavy stone,

And, bearing that heavy weight,

I shall sing a joyful song.

Lesya Ukrainka

Among those who “sowed flowers on the frost” was Oksana Yakivna Meshko, whom all of Ukrainian—so small!—Kyiv, already respectfully called “Baba Oksana.”

When on August 1, 1975, in the capital of Finland, the heads of European states, the USA, and Canada (including the USSR) finally signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE), which, at least formally, obliged Brezhnev’s clique to adhere to the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a brilliant idea was born in intellectual circles: to create public groups to promote the implementation of the Helsinki Accords. Such a cunning name was intended to mask an attempt to expose and publicize human rights violations. The first to be established, on May 12, 1976, was the Moscow Group. The second—the Ukrainian.

Here is how Oksana Yakivna told Vasyl Mykytovych Skrypka about this on her 85th birthday:

“In the autumn of 1976, Mykola Danylovych Rudenko came to me with his wife Raisa with a proposal to join the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords. ‘And who else is in the group?’ I ask. He says: ‘Well, me, and you will be the second.’ ‘But,’ I say, ‘who will bring parcels to my son and send packages?’ Rudenko was surprised, but said to me without laughing: ‘My God, Oksana Yakivna! You are so frightened that you thought we could be arrested! But our Ukrainian Public Group will be based on the Helsinki Accords, which were concluded on August 1, 1975.’”

…So I sat and thought. I said: “There are only two of us now.” “There will be more of us, Oksana Yakivna, don’t be afraid that there are only two of us. We are just forming the core. There will be more.” I say: “But you know that we will all be arrested later.” “Oh, no!” Here he was already laughing. “We won’t be arrested!” I say: “We will be arrested. Because a wolf may change his coat, but not his nature. I have now, Comrade Rudenko, in defending my son and dealing with our judicial and state institutions, with the justice system, become convinced that it is all the same: we will be arrested. But I want to tell you—don’t laugh—I am not afraid of being arrested. Because it would even be better for me to be arrested, because life is hard for me now. I cannot live like this anymore.” I agreed. I became the second member.” (I Bear Witness, p.14).

As soon as Radio Liberty announced on November 9, 1976, that Mykola Rudenko, at a press conference in Oleksandr Ginzburg’s apartment in Moscow (there were no accredited foreign journalists in Kyiv), had announced the creation of the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords—two hours later, bricks flew through the windows of his home in Koncha-Zaspa near Kyiv, where his wife Raisa Rudenko and Oksana Meshko were spending the night. The women shielded themselves with blankets and pillows, but Oksana Meshko was still wounded in the shoulder. This, Mykola Danylovych Rudenko still jokes, was the KGB’s salute in honor of the creation of the UHG.

Standing on completely legal, constitutional grounds (the Final Act of the CSCE was equated with national legislation), and acting openly, the Ukrainian Helsinki Group collected and publicized facts of human rights violations in Ukraine. Some of its members hoped that such a tactic would allow them to spin—albeit a very thin—thread of national resistance for a long time, just so it would not break completely. It was said that Oksana Yakivna was counting somewhat on her 10 years served for nothing, “in advance.”

But already on February 5, 1977, Oleksa Tykhy and Mykola Rudenko were arrested, on April 23—Mykola Matusevych and Myroslav Marynovych, on September 22—Heliy Sniehiryov (he, admittedly, was not formally a member of the UHG), on December 12—Levko Lukyanenko… The Cossacks went to war—and the entire burden of the struggle for the nation’s survival fell on female shoulders. Cossack mothers, wives, and fiancées, while raising Cossack children (our language has not coincidentally recorded that in Ukraine it was harder to hide and protect them; in Russian, it is “vospitat’,” i.e., to nurture). So, while raising little Cossacks, they also had to take up the plow handles (“Oh, beyond the grove, the grove, the little green grove, a young maiden was plowing with a little black ox…”). Or even the sword, like the heroic defenders of Busha, like Olha Basarab and Kateryna Zarytska. And most of all, they took care that our spiritual sword would not be dulled—they protected the faith and the purity of morals and customs, created songs, like Marusya Churai, Lesya Ukrainka, and Lina Kostenko, and stood up for the rights of their tortured husbands and sons, and thus for their entire enslaved nation.

After Mykola Rudenko’s arrest, it was decided not to elect a new head of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, but in fact, the coordination of its actions fell on Oksana Yakivna’s shoulders. Indeed, after the arrest of Oles Berdnyk, she practically remained perhaps the only truly active member, as all the others were either behind bars or under administrative supervision. She diligently guarded the purity of the Group, carefully, sometimes it seemed too zealously, vetting every candidate. Some grumbled: she suspects almost everyone of being a KGB agent. But the result proved to be appropriate, may God forgive such a comparison. Among the twelve disciples of Jesus Christ, there was one apostate. And among us, only one repented after five years of imprisonment (Oles Berdnyk). And one more emigrated (Volodymyr Malynkovych). Four paid with their lives in captivity—Oleksa Tykhy, Yuriy Lytvyn, Valeriy Marchenko, Vasyl Stus. One committed suicide before his arrest (Mykhailo Melnyk). 24 members of the Group were arrested and spent a total of over 170 years in prisons, concentration camps, psychiatric hospitals, and in exile. In total, the Group had 41 members from 1976 to 1988, 39 of them political prisoners, with over 550 years of captivity on their tormented record, including 15 years for Oksana Yakivna. Former and then-current female political prisoners Nina Strokata-Karavanska, Nadiya Svitlychna, Iryna Senyk, Stefania Shabatura joined the Group; for her participation in the Group, Olha Heyko-Matusevych was imprisoned; following her husband into captivity went Raisa Rudenko; Hanna Mykhailenko was confined to a psychiatric torture chamber for 8 years. Stefania Petrash-Sichko, whose husband and two sons were imprisoned, Vira Lisova, Svitlana Kyrychenko-Badzio, Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, Olena Antoniv, Nina Marchenko—all held themselves with dignity and acted heroically…

While still formally at liberty, Oksana Yakivna found herself under tight surveillance after the arrest of the Group’s founding members. “I was left all alone, like a thorn in the KGB’s side, so I experienced tremendous pressure from the authorities. Constant searches, they would catch me on the street, force me into a car, take me to the KGB, interrogate me and persuade me to abandon this cause, warning that it would end badly,” testifies Oksana Yakivna. (I Bear Witness, p. 15).

During the first two years of the UHG’s activity, the human rights activist’s home was searched nine times, her garden plot was dug up several times in search of “sedition,” an armed attack by a “robber” was staged at her door, hoping to induce a heart attack, and a surveillance post with night vision equipment was set up in the building opposite. The house at 16 Verbolozna Street was like a snake pit: anyone not immediately seized there would invariably leave with a “tail,” people were searched on the road, robbed, blackmailed, beaten, arrested…

Sometimes Baba Oksana would leave her home through a window to go to important meetings or to deliver materials for the Group. When she had nothing of the sort, she would demonstratively take off her glasses, get on a bus, and go where she needed to. The bus would sometimes be stopped on the way (as when she was going to Lukyanenko’s trial in Horodnia), and she would be forced off: get home, baba, however you can… But stopping her herself was no longer possible. “I was not only no longer afraid of anything, but I considered it my civic duty and my destiny,” she wrote. When Vasyl Skrypka told his countrymen about her, one of them said: “If there were five such grandmothers in Ukraine, the entire KGB would have a heart attack” (I Bear Witness, p. 3).

And so the KGB resorted to a tried-and-true method—psychiatric blackmail. In June 1980, Oksana Meshko was forcibly taken to the Pavlov Psychiatric Hospital for an “examination,” where she was held for two and a half months in a ward with sick patients. Despite intense pressure on the psychiatrists, attempts to portray the human rights activist as mentally ill (and thus confine her to compulsory “treatment”) failed—the Pavlov doctors refused to have such a sin on their conscience.

At the end of summer, Oksana Meshko finally managed to escape from Pavlivka. “I understood,” she recalled, “that my time at liberty was very short. And I sent a similar telegram to my son (in exile—V.O.), and I was ready myself. In the meantime, I went to my grandson’s school every day. He was in the first grade then. I was with him during the short breaks. And during the long break, I took him with me—to the park, the square, I would give him something to eat. We talked. It was a wonderful autumn. Beautiful! I will never forget…”. (I Bear Witness, p. 23).

Her premonition did not deceive her. On October 12, 1980, KGB agents conducted another search of Oksana Yakivna’s house, which lasted late into the night. Finding nothing, they finally left. She could not sleep for a long time. She opened all the windows in the house, doused the floor with water, and washed it. “That terrible smell haunted me. These people have a particular smell… Maybe it’s tobacco. Or stale breath. Or maybe they were morally decomposing from within…”. (I Bear Witness, p. 24). Only towards morning, after taking a sleeping pill, did she manage to sleep for a short while. And the next day—a knock on the door. “I looked out the window: KGB… I realized my freedom ended here. I gathered what is immediately necessary when a person finds themself behind bars… I took a small book, gathered my glasses, toothbrush, a small towel, a change of underwear. I locked the windows, the doors, and left.

I never returned here.” (I Bear Witness, p. 24).

After interrogations and another forensic medical examination at Pavlivka (in vain—the doctors again did not declare O. Meshko mentally ill), the KGB staged a shameful trial for themselves over an “especially dangerous state criminal”—an almost 76-year-old woman. They tried her with diabolical, one might say, cynicism—right on Christmas, January 5–7, 1981. The verdict of that sham trial: six months of imprisonment and five years of exile for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda,” Part I, Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR. They thought that would be quite enough for the old woman. And to be certain—they transported her across their entire empire to her place of exile—the small town of Ayan on the shore of the Sea of Okhotsk—a journey of 108 days.

Here is that transport:

“The next day I was before the large prison gate. I looked back at the high fence—a cement wall. And I realized: I am on Kholodna Hora in Kharkiv. When the gate opened and I walked with my belongings, my eyes were as if covered by a veil, tears streamed down. I knew that somewhere through this gate in 1920 my father, Yakiv Pavlovych Meshko, a 42-year-old man, had been led, and shot right here. He is buried somewhere in a mass grave. I knew that he died on Kholodna Hora. Imagining how he walked through this gate, I felt as if I were stepping in his footprints. Through this gate also passed my nephew, Vasyl Khudenko. Vasyl Khudenko’s wife, Nadiya Kandyba. My uncle, Dmytro Petrovych Yanko. How many more of my relatives passed through here, whom I may not even know, who passed through this Ukrainian Golgotha—Kholodna Hora…”. (I Bear Witness. pp. 32-33).

What that transport cost an old, sick woman is frightening to imagine. It was truly a martyr’s road between death and life. The guards, at times, would refuse to take her, because they didn’t want to “transport corpses.” She herself would have to plead: “It’s such an article [of the criminal code] that they will transport me anyway. Dead, but they’ll transport me.” (I Bear Witness, p. 34).

In Ayan, her son Oles was serving out his exile. The mother perfectly understood the choice the KGB had placed him in by exiling her specifically there. On the distant homeland—his wife, who was ill with a leg condition at the time, was alone with a newborn daughter and a third-grade son. In a foreign land—his old mother. And she firmly, sternly ordered: “Son, go, save your family.”

Before his departure, Oles repaired the flimsy Yakut hut, prepared as much firewood as he could, and jumped onto the last steamboat before winter…

The hut, just 300 meters from the shore of the Sea of Okhotsk, would be so snowed in during blizzards that for several days she couldn't get out of it. She would hire people in advance for half a liter of vodka to dig her out. But the KGB agents would scare off those willing: let her, they’d say, get snowed in. “There were cases,” Oksana Yakivna recalled, “that the wind would break the power lines, and I would be left in the hut without light. I burned a candle. The windows were snow-covered. The doors were snow-covered, and I am alone in that hut. And you don’t know when you will get out into the light of day. This hut is by the road. People, passing by, would ask: ‘Is she in there? Is she alive?’ A neighbor said: ‘Well, she must be alive, because yesterday there was still smoke coming from the chimney.’ That’s how I signaled to people that I was still alive.” (I Bear Witness, p. 39).

The years of exile dragged on like decades. However, Oksana Meshko did not fall into despair: “I did not give free rein to my sorrow and my pessimism. I am not a pessimist by nature, but in those conditions, one could go mad,” she recounted. “But each time I mobilized myself for a walk, for work, for prayer. I believe that prayer and turning to God helped me to endure that terrible captivity.” (I Bear Witness, p. 40).

Despite the expectations of her tormentors, the indestructible Oksana Yakivna Meshko withstood this ordeal as well. She once told me: “I will outlive Brezhnev yet.” And she did, and not just him. She outlived, in fact, the Soviet empire itself, which by the end of her life was already cracking, shaking, convulsing in its death throes.

At the end of 1985, Oksana Meshko returned from exile. The changes taking place in society she initially met with incredulous surprise, but soon, with her characteristic energy and optimism, she actively joined the process of socio-political renewal. In 1988–1989, at the invitation of the Ukrainian diaspora, she traveled to Australia for eye surgery. The KGB agents spitefully advised her: “Go, go, Oksana Yakivna. And don’t come back.” “No, I will indeed come back. On your heads!”

Seeing that Ukrainians abroad viewed perestroika with skepticism, she convinced them that a favorable situation had arisen to launch a broad movement for Ukrainian statehood. She spoke in the Australian Parliament about the situation in Ukraine. She returned via the United States, where she participated in the work of the World Congress of Free Ukrainians. She launched a campaign for the release of Levko Lukyanenko and other political prisoners. Meeting with journalists and state officials, speaking at public gatherings, she everywhere defended and popularized the Ukrainian idea.

Returning to her homeland in early 1989, Oksana Yakivna became one of the leaders of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, created on July 7, 1988, on the basis of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, and joined its Coordinating Council. It was she who, on April 29, 1990, opened the congress of the UHU, at which this public organization, which from the very beginning was a proto-party and aimed for independence, was reformed into the Ukrainian Republican Party. In June of the same year, primarily through her efforts, the human rights organization was renewed—the Ukrainian committee “Helsinki-90” was created. Oksana Yakivna remained its soul and driving force until her last days. No rally was complete without her. Together with other former political prisoners, she supported the student hunger strike in October 1990 with a one-day fast.

At the end of December 1990, she felt unwell. But she had to take her cane and go out nonetheless. It was icy, and to make matters worse, someone stole her cane, which she had placed in a corner in a shop. Oksana Yakivna fell and suffered a stroke (or perhaps it was the other way around). For several days she did not regain consciousness, but even during brief moments of clarity, she could no longer speak. On January 2, 1991, her seemingly tireless heart stopped beating. But it had already done its holy work—that year, the Evil Empire fell and an independent Ukraine arose.

Oksana Yakivna Meshko was buried on January 5, 1991, at the Baikove Cemetery in her mother’s grave, under an iron cross with the inscription: “Mariya Hrab (Meshko). 26.I.1880–13.XI.1951”. And there was no sign that her daughter was also buried here. Therefore, the community collected funds and in 1995 erected two Cossack crosses on that grave, which were carved from stone by Mykola Malyshko.

Yuriy Lytvyn (may he rest in peace), loved Oksana Yakivna like a child and called her our Joan of Arc. Analogies sometimes obscure the image—I preferred it when he said, in the words of Bohdan Khmelnytsky: “The Cossack mother is not yet dead!” And there, in the distant Urals, in fierce captivity, our hearts grew warmer when we remembered that we have such a sleepless, all-loving, and immortal Cossack Mother.

Bibliography.

1.

Between death and life. By Oksana Meshko. Translated from Ukainian by George Moshinsky. N.Y. Toronto – London – Sydney: 1981. – P. 171.

Oksana Meshko. Between Death and Life. K.: NVP “Yava”, 1991. – p. 92.

Oksana Meshko. The Mother of Ukrainian Democracy. Prepared for publication by Vasyl Skrypka. Journal “Kryvbas Courier” 1994, issues 2–7.

Oksana Meshko. I Bear Witness. Recorded by Vasyl Skrypka. Library of the journal “Respublika.” Series: Political Portraits, no. 3.— K.: Ukrainian Republican Party, 1996. – p. 56.

2.

The Ukrainian Helsinki Group. 1978–1982. Documents and materials. Compiled and edited by Osyp Zinkevych. “Smoloskyp” Ukrainian Publishing House named after V. Symonenko. Toronto–Baltimore. 1983. pp. 471–492.

Oksana Meshko, Cossack Mother. On the 90th anniversary of her birth. Memoirs. Compiled by V. Ovsienko. K.: URP, 1995. – p. 64.

Vasyl Ovsienko. The Light of People. Memoirs-essays about Vasyl Stus, Yuriy Lytvyn, Oksana Meshko. Library of the URP journal “Respublika.” Series: Political Portraits. – K.: 1996, No. 4. – p. 108.

H. Kasyanov. Dissenters: the Ukrainian Intelligentsia in the Resistance Movement of the 1960-1980s. – K.: Lybid, 1995. – pp. 86, 147, 161, 167, 168, 170, 171.

The Ukrainian Helsinki Group. On the 20th Anniversary of Its Creation. Documents. History. Biographies. Publication of the Ukrainian Republican Party. Kyiv, 1996. p. 19.

A. Rusnachenko. The National Liberation Movement in Ukraine. K.: Olena Teliha Publishing House. 1998. – pp. 19, 210-213, 219.

The Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: Documents and Materials. In 4 volumes. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; Art designer B.F. Bublyk. Kharkiv: Folio, 2001. Compilers Ye.Yu. Zakharov, V.V. Ovsienko.

January 1991, 2001.

Published in:

Ovsienko Vasyl. The Light of People: Memoirs and Commentary. In 2 books. Book I / Compiled by the author; Art designer B.Ye. Zakharov. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; K.: Smoloskyp, 2005. – pp. 309–322.

Vasyl OVSIENKO.

THE EXALTATION OF THE HOLY CROSSES

…Mary therefore took a pound of expensive ointment made from pure nard, and anointed the feet of Jesus and wiped his feet with her hair… But Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples… said, “Why was this ointment not sold for three hundred denarii and given to the poor?” …Jesus said, “Leave her alone, so that she may keep it for the day of my burial. For the poor you always have with you, but you do not always have me.”

Gospel of St. John, 12: 3–8.

Oksana Yakivna Meshko was buried on January 5, 1991, at the Baikove Cemetery in her mother’s grave, under an iron cross with the inscription: “Mariya Hrab (Meshko). 26.I.1881–13.XI.1951”. And there was no sign that her daughter was also resting here. Therefore, among former political prisoners in Kyiv, the idea matured: it is not right for the grave of a world-renowned public figure, a great devotee of the Ukrainian spirit, Oksana Yakivna Meshko, to remain without a memorial sign.

I approached the artist Mykola Malyshko, who had previously carved stone Cossack crosses for the graves of Oleksa Tykhy, Yuriy Lytvyn, Vasyl Stus, Ivan Honchar, and Ivan Svitlychny. Malyshko developed a project and advised ordering the crosses in Terebovlia in the Ternopil region, where red sandstone is quarried. I took it upon myself to collect memoirs about Oksana Meshko, publish them as a separate brochure at the URP, where I then worked as a secretary, and use this little book to raise money for the crosses, charging several times its cost, as well as accepting donations.

The booklet was published in 1995 under the title “Oksana Meshko, a Cossack Mother” with a print run of 1,000 copies. It contained memoirs by Yevhen Sverstiuk, Mykola Rudenko, Mykhailo Horyn, Levko Lukyanenko, Vira Lisova, Petro Rozumny, Svitlana Pohuliaylo, Borys Dovhalyuk, Yuriy Murashov, and myself. A total of 64 pages, many photographs, as well as the design for the crosses and an appeal to readers to collect money. We passed a portion of the print run to the Ukrainian diaspora in the USA and Canada. At the URP, we created and circulated a “Memorial Certificate,” in which we inscribed all donors, and in return, each received a booklet of memoirs. Over a year and a half, more than 400 people contributed from their honest labors. We published their lists in the URP newspaper “Samostiyna Ukraina” three times: on April 3, 1995, January 8, 1996, and in June 1996, issue 13 (200). First and foremost, we should thank the former political prisoners—friends of Oksana Yakivna, women’s organizations in the diaspora and in Ukraine, for they collected the most money. These included the Plast troop “Verkhovynky” (leader Nina Samokysh, scribe Oleksandra Yuzeniv, member Nadiya Svitlychna), the Sisterhood of Saint Olga at the Parish of St. Andrew the First-Called in Washington, the Association of Ukrainian Orthodox Sisterhoods (Nina Strokata-Karavanska), the Ukrainian Women’s Committee of Canada (Olha Zaveryukha-Svyntukh), the Social Service of Ukraine (Ruslana Bezpalcha), the Union of Ukrainian Women (Atena Pashko), and the Women’s Hromada (Mariya Drach). The community of St. George UGCC in Minneapolis, the “Golden Cross” society, and the Congress of Ukrainian Canadians also donated. In Ukraine, the booklet was actively distributed and money was collected by the benefactresses Yevhenia Kozak, Vira Lisova, Ruslana Bezpalcha, Olena Burmystrova, Kateryna Kryvoruchko, Tetyana Kosareva, Olha Stokotelna from Kyiv, Liuba Korotenko in the Donetsk region, Petro Rozumny in the Sicheslavshchyna region, Ivan Polyovy in the Ternopil region, and Viktor Nesterenko from Voznesensk. A significant portion was collected by URP organizations. It was a time of inflation; the account was in millions of karbovantsi, which we prudently exchanged for dollars. The cost of the booklet was 50,000 karbovantsi—about half a dollar, but we charged at least double. But even the “widow’s mite” was dear to us, because it was given from a sincere heart, torn from earnings or a pension.

The enterprise “Terebovlyahaz” (director Vasyl Wenger) quarried red sandstone for the crosses, carved one of them, and quarried and cut a block for the second, charging only for the workers’ wages, and delivered them to Kyiv at their own expense. Mykola Malyshko and his brother Petro hand-carved the second cross, and on October 28, 1995, we erected them. One already had an etched pattern, and on the second, the brothers carved flowers while it was standing, beginning the work in the autumn and finishing in the spring.

Not all work was paid for, as this was a public, holy matter; people considered it an honor to be involved. For example, when it came to clearing around the graves, unloading the cross and the stone block, pulling them on rollers, and installing the crosses, we gathered a whole crowd of people. Mykola and Petro Malyshko directed the work, and the “Sich granddad” Volodymyr Marchenko—a permanent representative of the Cossack society of the Kyiv region—led the Cossacks, although it was usually Pani Yevhenia Kozak who commanded the Cossacks. The Cossacks Pavlo Sharovara, Petro Senchenko, Ivan Kovalenko, Mykola Makedon, Oleksandr Kolomiyets, Anatoliy Mayster worked there. Also working were Petro Romko, Vakhtang Kipiani, Mykola Shulyk, Yevhen Obertas with his son Oles, Volodymyr Nedilko, Oles Tymoshenko, Vitaliy Shevchenko, Oksana Meshko’s son Oles Serhienko, and other good people.

On the Ascension of our Lord in the year of our God 1996, on May 23, Father Yuriy Boyko (UAPC) consecrated the crosses. About one hundred and fifty people gathered then. Thus, as a result of a year and a half of effort, a good deed was completed with God’s help.

Meanwhile, I learned that in those last January days of 1990, when we honored Oksana Yakivna at the House of Writers, Doctor of Philology Vasyl Mykytovych Skrypka recorded her story about the events of the 70s and 80s: human rights activities, the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, confinement in a psychiatric hospital, arrest in 1980, the trial, the 108-day transport, and exile in Ayan on the shore of the Sea of Okhotsk… This story, stunning in its factual basis and artistic power, was partially published in the journal “Kryvbas Courier,” issues 2–7, 1994, under the title “The Mother of Ukrainian Democracy.” I seized upon that text, found out from Vasyl Skrypka that his audio recording was all the way in the United States, with Nadiya Svitlychna. Mykhailo Horyn brought it to me, I listened to it, added what had been omitted, and with Vasyl Skrypka’s consent, prepared the entire text for publication—these priceless testimonies about a wicked colonial era which, God willing, is now passing—may it never return. The booklet was published with the same public funds at the URP Duplicating Center under the title “I Bear Witness.” It also included the verdict in her case, cynically delivered by the Kyiv City Court (Dotsenko I.A., Topchiy O.M., Maksymyshyna N.L.) on Christmas Day itself, January 7, 1981. I wrote this foreword to it with the epigraph cited above.

On January 30, 1990, a kindred and heartfelt company, recently hardened in concentration camps, gathered at the House of Writers in Kyiv to honor the outstanding public figure, co-founder of the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords, and prisoner of Stalin’s and Brezhnev’s Gulags, Oksana Yakivna Meshko, on the occasion of her 85th birthday. This was, by far, the first public honoring in her life. Fine words were spoken—but who remembers them now? And who would have thought that this was not only the first, but also the last time we would celebrate our Cossack Mother’s birthday in this way? For on January 2, 1991, her seemingly tireless heart stopped beating…

“Spiritual feats do not perish in vain,” said His Holiness Patriarch Volodymyr (Romaniuk) on the last day of his earthly life. “There will always be someone to testify about them.”

Perhaps that is why on January 31 and February 1, 1990, the Lord guided the steps of the good man Vasyl Skrypka to the home of Oksana Yakivna, where he recorded her autobiographical account—honest, dramatic, dignified, lofty in style, and majestic in spirit. For such was this Ukrainian woman. About selfless maternal love, about the defense of the rights and dignity of each of us, about the desperate struggle of a lonely elderly woman against an entire foreign empire of evil, against a whole host of informers, operatives, KGB agents, psychiatrists, investigators, judges, guards, and wardens…

This is a testimony to posterity, so they may know the invaluable worth that the Sixties generation defended—and won for them—freedom of speech, the most important of freedoms.

This is so that we may look around and see with whom we walk this earth. And so we may timely honor those who will not be with us for long.

To this, it should be added that on Sunday, September 22, 2002, in Stari Sanzhary, festivities were held on the occasion of naming the local school after Oksana Yakivna. She had studied at this school. In the presence of the entire school and many villagers, the head of the Novosanzharsk district council, Volodymyr Petrushko, announced the resolution to name the school after Oksana Meshko. The unveiling of a memorial plaque on the school building in Stari Sanzhary was attended by the head of the district state administration Andriy Reka, Taras Shevchenko National Prize laureate Yevhen Sverstiuk, associate professor Ivan Brovko, and publicist Vasyl Ovsienko, who knew this great devotee of the Ukrainian spirit well. A museum dedicated to Oksana Meshko will be created in Stari Sanzhary.

Samostiyna Ukraina. – 1995. – Nos. 11-12. – March 28; 1996. – No. 13. – June; Nasha Vira. – 2002. – No. 10 (174). October. – p. 16.

Published in:

Ovsienko Vasyl. The Light of People: Memoirs and Commentary. In 2 books. Book I / Compiled by the author; Art designer B.Ye. Zakharov. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; K.: Smoloskyp, 2005. – pp. 323–328.

Photos:

Meshko Oksana MESHKO.

Meshko-Ovs “It was I who put Vasyl in prison,” confessed O.Ya. Meshko on January 30, 1990. Photo by Mykola Horbal.