HE ROSE AND FELL

(OLEKSA TYKHY)

A few more years – and the bonds will break.

Barbed wire will enter the dreams of children.

And all the prophetic signs

Will seek to fall upon us.

Vasyl Stus.

It seems the barbed wire bondage that tightly bound generations of Ukrainians has broken. God grant it is forever. But not everyone knows – and some do not want to know – by whose and what superhuman efforts that barbed wire was torn apart. And that these people were not “made of iron, plastic, glass and concrete,” as Vasyl Stus wrote, but were molded from the same clay as each of us. That their bodies felt pain and cold just the same, as anyone’s does; that they longed for nourishment, warmth, and affection, just like every one of us. And the Lord did not forge these people in a fiery furnace; they emerged from the same reality of life as all of us. That they were not born heroes, as some now try to portray them, as if to explain their own non-participation in those not-so-distant events. They stood out from the crowd of “ordinary Soviet people” in one respect: they behaved normally, in accordance with the tenets of Christian moral teaching and with national traditions. And when the vast majority of Ukrainians bent and adapted to abnormal behavior, the lives of normal people against such a backdrop truly seem like a heroic feat.

Oleksa Tykhy was such a champion of the Ukrainian spirit. He died in a Perm prison on May 5, 1984, in the 58th year of his life. Before that, he was serving his sentence in the special-regimen camp VS-389/36 in the village of Kuchino, Chusovskoy District, Perm Oblast, in the Urals, where I had occasion to spend several months with him in the same cell.

Ukraine remembers the reburial on November 19, 1989, of three human rights defenders and political prisoners who died in captivity in the mid-1980s: Vasyl Stus, Yuriy Lytvyn, and Oleksa Tykhy. That mass funeral, the likes of which had not been seen since the reburial of Taras Shevchenko, became one of the most significant milestones on our path to independence. Astonished passersby asked: who are they burying? They were burying “especially dangerous state criminals,” “recidivists.” Why were they being accorded such honors? People had heard something about Stus, less about Lytvyn and Tykhy, but they were all paid equal tribute, for the measure of each man’s sacrifice was the same: his life.

Those “prophetic signs,” upon which we now try to build our Ukraine, truly did fall upon certain individuals. Upon them, as on iron pillars, our spiritual sky rested – and did not collapse! – even in the darkest times of our destruction as a people. And these pillars stood all across Ukraine. Honoring Oleksa Tykhy of Donetsk, let us remember his fellow countrymen – intellectuals and citizens who would bring honor to any nation: Mykola Rudenko, Nadiya and Ivan Svitlychny, Vasyl Stus, Ivan Dziuba. To the credit of the people of Donetsk, they proved especially resilient in defending Ukrainian truth against a whole legion of liars, hypocrites, and lackeys – the entire ideological apparatus of the Evil Empire.

Here are excerpts from Oleksa Tykhy’s article “Thoughts on My Native Donetsk Land,” written at the end of 1972. (Published through my efforts and those of Anatoliy Lazorenko in the journal “Donbas,” No. 1, 1991, pp. 136–158). O. Tykhy had sent it to the then-Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, I.S. Hrushetsky.

“I am a native and resident of the Donetsk region. I am 46 years old. I studied in Soviet schools and graduated from the philosophy department of Lomonosov Moscow State University. I have worked in a school, been in prisons and camps, and worked in a factory. I currently work as a grade 4 fitter-assembler.

I was taught, and I have taught, that man does not live by bread alone; that the meaning of life is in doing good for people, in raising the material and cultural level of the people, in the search for truth, in the struggle for justice, national pride, and human dignity, and in civil responsibility for everything that happens during my lifetime.

Who am I? What is my purpose? These questions have never left me. I have constantly thought about them, and I am constantly searching for answers.

Today, I think:

1. I am a Ukrainian. Not just an individual endowed with a certain appearance, the ability to walk on two limbs, the gift of articulate speech, and the gift of creating and consuming material goods. As a citizen of the USSR, as a ‘Soviet man,’ and above all as a Ukrainian, I am a citizen of the world—not as a rootless cosmopolitan, but as a Ukrainian. I am a cell in the eternally living body of the Ukrainian people. Individual cells of any organism die, but the organism lives on. Individual people sooner or later die one way or another, but the nation lives on, for the nation is immortal. (...)

I love my Donetsk region, its steppes, ravines, forest belts, and spoil tips. I also love its people, the tireless workers of the land, factories, plants, and mines.

I have always loved it, and I love it today, it seems to me, in this hour of adversity, assimilation, and indifference of my fellow Ukrainians to their national culture, even to their native language (...) And if I lack the talent or gift to glorify it further, that is not my fault, and I hope I will be forgiven for it.

2. My purpose is to ensure that my people live, that their culture rises, that the voice of my people worthily carries its part in the polyphonic choir of world culture. My purpose is to ensure that my fellow Donbas people produce not only coal, steel, machines, wheat, milk, and eggs. To ensure that my Donetsk region produces not only football fans, rootless scientists, and Russian-speaking engineers, agronomists, doctors, and teachers, but also Ukrainian specialists who are patriots, Ukrainian poets and writers, Ukrainian composers and actors.

3. I am, apparently, a poor patriot, a weak-willed person, for seeing the injustices done to my own people and the primitivism of people, and being aware of the bitter consequences of the current education of children and the exclusion of millions of my fellow countrymen from cultural development, I content myself with satiety, with idle daydreams, and with crumbs of culture just for myself. And I have neither the courage nor the will to actively fight for the fate of my silent, downtrodden countrymen—the people of Donbas—for the flourishing of our national culture in the Donetsk region, for the future.

It is not the fault, but the misfortune of ordinary people (that is, hardworking laborers and peasants), that with their consent or by their silent acquiescence, the Ukrainian language and culture in the Donetsk region are being destroyed.

It is not a misfortune, but the fault of every intellectual, every person who has received a higher education and holds a leadership position but lives only to stuff his own belly, indifferent as a log to the fate of his people, their culture, and their language.

And should not the activities of public education authorities, teachers, cultural institution workers, and all leaders in the field of assimilation of millions of Ukrainians in the Donetsk region be qualified as a crime? After all, such mass assimilation can only be called intellectual genocide. (...)

I am an internationalist by conviction; I wish freedom, national independence, and material and cultural development for the Vietnamese, Indian, and Arab peoples, for the peoples of Africa, Asia, America, and all others. On this Earth, there should be no hungry, colonial, backward, or small peoples. Let every nation live on its own land, let it create culture and science to the best of its ability and share its achievements with all the peoples of the world. I want the Ukrainian people, including their part—the people of Donbas—to contribute their share to the treasury of world culture.” (pp. 141–142).

This, I remind you, was written in 1972, when Suslov’s propaganda was proclaiming the national question in the USSR to be completely and finally resolved – and at the same time, Andropov’s gang was carrying out another pogrom against the Ukrainian intelligentsia.

Oleksa Tykhy managed to put on paper only a fraction of what he thought. In addition to the aforementioned work, the articles “Reflections on the Ukrainian Language and Culture in the Donetsk Oblast” (January 2, 1972) and “Workers’ Free Time” (April 15, 1974) have survived. (They were published in the brochure Oleksiy Tykhy. Reflections. A Collection of Articles, Documents, and Memoirs. Compiled by O. Zinkevych. Ukrainian Publishing House “Smoloskyp” named after V. Symonenko, Baltimore–Toronto, 1982, 80 pp.), as has “Rural Problems” (1974). He was also compiling a “Dictionary of Words That Do Not Conform to the Norms of Standard Literary Ukrainian (Foreign Words, Corrupted Words, Calques, etc.).” I have in my hands 63 pages of typescript, up to and including the letter “M.” O. Tykhy provides the corrupted word, in the second column the correct word, and in the third the source from which it came. But Oleksa Tykhy’s greatest work is a collection of quotes from famous people on the importance of language, “The Language of a People. The People,” which is 303 pages of dense typescript. He quotes about 450 authors. This work was conceived as a manual for teachers. In 1976, the author took a copy to the Institute of Philosophy and presented it to Professor Volodymyr Yukhymovych Yevdokymenko, a well-known “fighter against Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism.” (See the book: V.Y. Yevdokymenko. A Critique of the Ideological Foundations of Ukrainian Bourgeois Nationalism. 2nd edition, revised and expanded. Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 1968. 294 pp.). He gave a second copy to an equally famous “fighter” in the field of informing, Professor Illia Isakovych Stebun (Katsnelson) of Donetsk University. The result was an immediate denunciation of the latter to the KGB and incriminating testimony from him and lecturer L.O. Bakhaieva at the 1977 trial, stating that “Tykhy, in their presence at the department, expressed… malicious, slanderous fabrications that defame the Soviet state and social system.” However, the Department of National Relations of the Institute of Philosophy of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR had recommended the book to the “Radianska Shkola” publishing house. True, this happened a month and a half before the author’s arrest, so it was transferred from there to the KGB. This book would be so useful for today’s teachers, because the language situation, at least in the Donetsk region, has not improved. Oleksa Tykhy also translated Jerzy Jędrzejewicz’s “Ukrainian Nights, or the Lineage of a Genius” from Polish. This book about T. Shevchenko was not published in our country until after independence.

A man of colossal intellectual potential and outstanding pedagogical talent, Oleksa Tykhy could not become a great educator and scholar under a colonial regime, for instead of a university chair, he had hard labor. Nor did he become a statesman, because “in our God-blessed land,” the enemy diligently ensured that no leaders of the nation would rise from our midst who could lead their people “to the bright stars, to the quiet waters.” However, Oleksa Tykhy fulfilled himself as a man, as a Ukrainian who will be honored by those who live after us, for they will go on their journey through the centuries bearing the seal of his spirit (I. Franko).

My reader may have already noticed that I have not written about any former political prisoner with such passion (not that “false pathos”!) as I have about Oleksa Tykhy. But it is impossible to speak of him in other words. I am a philologist, and for the Word I was punished three times, so I know the value of the Word. Therefore, I testify: this was a man who approached the ideal where sainthood begins.

When I think of Oleksa Tykhy, I cannot shake the feeling that such people exist only in books. Arthur from Ethel Lilian Voynich’s novel “The Gadfly.” Or Martin Eden from Jack London’s novel of the same name. But Oleksa Tykhy was not a character in a book, but a living, heroic personality. A man of profound inner culture. He built himself, educated himself, tempered himself, and forged himself in the iron armor of a warrior, constantly improving himself and completely subordinating himself to the cause of Ukraine’s liberation. Completely. And he consciously laid down his bright head for it. He is a model of what a true man should be: tolerant and kind to others, but demanding and merciless with himself, always and everywhere firm and unyielding in his moral convictions, regardless of whether people see or appreciate it. Your conscience, that is, God, is always with you. He sees everything.

Among the political prisoners, there were no high-flown words, but honor was valued: everyone knew that he was not there just for himself. That he was on the front line, facing the enemy with his only weapon: dignity. And the honor of a people is composed of the dignity of each Ukrainian. Therefore, one must cherish one’s honor.

Oleksiy Ivanovych Tykhy came into God's world on January 27, 1927, on the farmstead of Izhivka in the Kostiantynivka district of Donetsk Oblast. His father, Ivan, a worker, died after the war. His mother, Maria, a peasant, died during his last imprisonment. His brother, Mykola, two years older, died in the war. Oleksa had two sisters, Zina and Oleksandra. Back in 1948, Oleksa was briefly imprisoned for criticizing a candidate in an election. He studied at transportation and agricultural institutes and worked in Zlatoust. He graduated from the philosophy department of Moscow State University. There he married Olga, and in 1949 their son Mykola was born. But he could not stay in Moscow and returned to Ukraine. He worked as a teacher in schools in the Zaporizhia and Stalino (now Donetsk) Oblasts, teaching history, Ukrainian language and literature, physics, and mathematics. He was a universal teacher who could and wanted to create his own school. He once proposed to the district education department that he take over a class and teach all subjects and handle all aspects of upbringing. Of course, he was not allowed to do so. Later, he was removed from teaching the humanities altogether.

In his youth, he formulated this life credo for himself:

“Why do I live?

1. For humanity, my people, and my family to live.

2. To do no evil to anyone, to show no indifference or injustice to anyone in their fate, difficult situation, or sorrow.

3. I am a conscious part of the Universe, of humanity, of my people, of my community where I live and work, and of my circle of friends and enemies. I am responsible for everything.

4. I have human dignity and national pride. I will not allow anyone to trample on either.

5. I despise death, hunger, poverty, suffering, and contempt itself.

6. I strive for my ‘self’ to be worthy of the name ‘human.’ In everything, always, regardless of the circumstances, I act according to my conscience.

7. To respect and value the work, beliefs, and culture of every person, no matter what level they may be at in comparison to my own, to generally accepted standards, or to the highest achievements of humanity.

8. To learn until my last breath and, if possible, without violence or coercion, to teach all who wish to learn from me.

9. To despise the powerful, the rich, and the influential if they use their power, wealth, and authority to mock, bully, or lord it over other people, or even a single person.

10. To be indifferent to those who live an animalistic life. As much as possible, I try to help each such person to realize they are human.

11. To study, support, and develop the language, culture, and traditions of my people.

12. To rid myself of and help others rid themselves of everything low, base, and alien to the spirit of humanity.”

(Journal “Novoye Vremya,” No. 51, 1990, pp. 36–37. My back-translation. – V.O.).

Strictly adhering to these principles, Oleksa Tykhy sent a letter to the Central Committee of the CPSU protesting the occupation of Hungary, for which he was arrested for the second time on February 15, 1957. Here are excerpts from the brief verdict of the Stalino Oblast Court of April 18, 1957 (published by L. Lukianenko in the book “I Will Not Let Ukraine Perish!,” Kyiv: Sofia, 1994, pp. 132-133):

“…expressed anti-Soviet views, stating that the Soviet school had allegedly reached a dead end and that communism was not being built in the USSR”; “that workers in collective and state farms are in a miserable state. He called the elections to the Soviets of People’s Deputies a comedy…”; “He justified the actions of the Hungarian counter-revolutionary rebels and called for the overthrow of the existing state system in the USSR.” The last part was likely an addition by the court, but:

“In the indictment presented, the defendant Tykhy, O.I., did not plead guilty but confirmed all the facts stated above, citing that his actions do not constitute a crime.”

He received 7 years of imprisonment in strict-regimen camps and 5 years of deprivation of civil rights under Art. 54-10 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR. He served his sentence in camp ZhKh-385/11 at the Yavas station in the Zubovo-Polyansky district of Mordovia. In captivity, he became close with the composer Vasyl Barvinsky, with the doctor Volodymyr Karkhut, whom he helped compile a book on medicinal plants, and with Yuriy Lytvyn and Levko Lukianenko.

When he was released in 1964, he was not allowed anywhere near a school – his beloved profession – not even within cannon shot. True, in the mid-60s he was allowed to work at an evening school in Oleksiievo-Druzhkivka, but this did not last long. They would not let him teach the way he wanted, and he could not teach the way the authorities wanted. He worked as a laborer, acquiring about a dozen skills, and willingly went for all kinds of retraining, as it gave him the opportunity to meet new people and to work in libraries in different cities. He traveled extensively to historical places, taking his son Volodymyr (born 1953) with him, often on bicycles. He visited many of his friends and fellow prisoners, distributing samvydav literature. Levko Lukianenko fondly recalls how Oleksa brought him, just released after 15 years, a three-liter jar of linden honey from his own apiary. And when the conversation later turned to creating the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, he warned him: “Don’t join the Group just yet. You’ve just gotten out of prison. Look how thin you are. Rest for a while. You’ll have time to go back to prison.” He was the only one who thought not of himself, but of another. He went himself, but did not push others. (Journal “Donbas,” No. 1, 1990, p. 138. Also L. Lukianenko’s essay “Oleksa Tykhy” in his book “I Will Not Let Ukraine Perish!,” Kyiv: Sofia, 1994, pp. 116–132).

But he himself, having come to visit the paroled Lukianenko in Chernihiv just as Mykola Rudenko was there with the first documents of the UHG, read them, added the fact of a search at his own home, and signed, thus becoming a co-founder. And, along with Rudenko, the first victim of the repressions against it. (See M. Rudenko. Life is the Greatest Miracle. Memoirs. Kyiv–Edmonton–Toronto: Takson, 1998.— pp. 433–434).

On June 15, 1976, during a search of Tykhy’s home, the typescript of “The Language of a People. The People” was confiscated. He was held in custody for two days “on suspicion of robbing a store.” During a search on December 24, 1976, they found a German Mauser system rifle, model 1898, which had been plastered into the clay in the attic of a small storeroom; Tykhy knew nothing about it. Perhaps his brother Mykola, who went to the front and was killed, had hidden it there during the war. And Oleksa also recalled how, during the search, they were about to tear up his floor because they found a note in his notebook: “firearm – floor [pol].” Oleksa himself then remembered that he had written down the title of a volume of the “Great Soviet Encyclopedia” that he was looking for to complete his set, since "pol" is short for "pol tom" or half volume, but can also mean floor.

Tykhy was arrested on February 4 (officially, the 5th), 1977, on charges of slandering the Soviet reality (Art. 187-I). But during the investigation, the case was reclassified as “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda,” Art. 62, Part 2 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR. Tykhy was also charged with “illegal possession of a firearm” (Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR)—that carbine found in the attic. Incidentally, his son Volodymyr knows that his father was held in Druzhkivka for several days and offered the chance to emigrate. He wouldn't even need to marry a Jewish woman. But Tykhy refused: “My place is here, not abroad.”

The trial in the case of Tykhy and Rudenko was a high-profile one, although it took place in the “Lenin Room” of the “Zmishchtorg” office, from which the sign was removed so it couldn't be found. Relatives were allowed into the courtroom only on the sixth day. (See, for example, my article “The Human Rights Movement in Ukraine”). It took place from June 23 to July 1, 1977, in the city of Druzhkivka, Donetsk Oblast. Tykhy was incriminated for his articles “Reflections on the Ukrainian Language and Culture in the Donetsk Region,” “Thoughts on My Native Donetsk Land,” “You and We,” “Rural Problems,” the texts of the UHG Declaration, the Group's Memoranda, and other documents, although Tykhy for the most part only signed the Group’s documents.

An experienced prisoner, he completely dismantled the prosecution’s case. Just look at the transcript, recorded from memory by his son Volodymyr. It is an example of iron logic, patience, perseverance, and dignity. (See the aforementioned brochure “Reflections,” pp. 37–50, and other publications, including ours: The Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: Documents and Materials. In 4 volumes. KHRG. Kharkiv: Folio, 2001. Vol. 2. pp. 129–149).

But the court had no intention of proving the facts of “slander against the Soviet state and social system,” let alone the aim of “undermining the existing system.” The court’s verdict had been predetermined by the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU. (See “Conversation with M. Rudenko” in the just-mentioned publication, vol. 1, p. 48).

As an especially dangerous recidivist, O. Tykhy received the maximum sentence under Art. 62, Part 2—10 years in special-regimen camps and 5 years of exile—while M. Rudenko also received the maximum for Part 1 of this article: 7 years in a strict-regimen camp and 5 years of exile.

The recidivist was sent to the “Sosnovka” camp in Mordovia. He already had a stomach ulcer there. He was transferred to a hospital in Nizhny Tagil and then returned to Mordovia.

Even with the change in circumstances, Tykhy did not lower the bar for himself. Levko Lukianenko related that when Oleksa began a hunger strike in the spring of 1978 to protest the inhuman conditions of detention for political prisoners, he, Lukianenko, tried to restrain him, because his suffering, let alone his death, would only please the torturers. “If I die, they will have to soften the regime, and it will be easier for you,” Oleksa believed. Alas, when one after another, first in Kuchino in the Urals, Andriy Turyk, Mykhailo Kurka, Ivan Mamchych, Oleksa Tykhy, Yuriy Lytvyn, Valeriy Marchenko, Akper Kerimov, and Vasyl Stus died, we were so corked up in a bottle that no information got out. And if there is no information in the world, there are no protests—so the testament of General Gendarme Andropov was carried out to the letter: prove to the world that there are no political prisoners in the USSR by exterminating us.

Oleksa endured a 52-day hunger strike then. That is on the verge of death. He was kept in a punishment cell. It happened to be mosquito season. As he lay on the floor, mosquitoes devoured him. There was no protection from them, and Oleksa no longer had the strength to wave them away. Finally, he was moved to the hospital. Yuriy Fedorov, who was in the next punishment cell and was saving himself from the mosquitoes by burning an old pea coat, was ordered to carry Oleksa out of the cell. Yuriy later said that he was surprised at how light he was, about 40 kilograms. And this had been a tall, once strong, handsome man.

In October 1978, Tykhy began a new hunger strike. He was thrown into solitary confinement. The doctor refused to treat him.

That year, a letter from Ukrainian political prisoners Oleksa Tykhy and priest Vasyl Romaniuk (later Patriarch of Ukraine) titled “The Historical Destiny of Ukraine: An Attempt at Generalization” slipped out of the camp. It is a brilliant example of publicistic writing. The authors proclaim the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the UN as the highest principle of common national and international coexistence, distance themselves from the policies and practices of the CPSU on the national question, and from its interpretation of the concept of democracy. They examine the consequences of Ukraine’s unification with Russia and express a wish for Ukraine's future independence. In the chapter “Possible Forms of Resistance,” the authors, for the sake of salvation from spiritual and cultural destruction, propose the following standards of behavior for Ukrainians:

“– To use only one’s native language in one’s native land and thereby strengthen oneself and one’s people.

– Not to send children to kindergartens and schools where Russian is the language of instruction; to demand schools and preschools with their native language or to teach children themselves.

– To refuse to study in schools and other educational institutions where Russian is the language of instruction; to demand schools, technical colleges, and universities with their native language and to study independently, taking exams as an external student.

– To communicate in one’s native language not only within the family circle but also at work, in public activities, and on the street.

– Not to attend theater, cinema, or concerts in Russian, as they negatively affect the culture of oral speech, especially among children and young people. The same applies to television and radio broadcasts.

– To refrain from vodka, profanity, and smoking tobacco.

– Not to use luxury items, especially those that have no artistic value and are of no benefit (passenger cars, expensive carpets, crystal ware, fashionable furniture, multi-volume editions of works that no one reads, pianos that no one plays).

– Not to accumulate money and valuables for their own sake, but to help people in trouble, talented children and young people whose parents cannot provide normal conditions for education and the development of creative talents, etc.

– To refuse to work in institutions, educational establishments, and public organizations where the Ukrainian language, national traditions, and human rights are disdained.

– To refuse military service outside of Ukraine and under commanders who do not speak Ukrainian.

– To refuse to work beyond the legally established norm of 41 hours per week, and on weekends, including in agriculture.

– Not to leave to work outside of Ukraine.

– To defend one’s rights, the rights of other people, freedom, honor, dignity, and to uphold the sovereignty of Ukraine.

– To identify and publicize any violations of the law, regardless of who commits them.”

Unfortunately, none of these words have become obsolete or outdated in Ukraine. These recommendations on how to survive as a Ukrainian in Ukraine remain relevant, because Ukrainianness continues to be in the position of a national minority in large territories. “But where, and when, was freedom won without sacrifice? Is it decent to live as a trembling animal, concerned only with one’s stomach, raising children to be rootless children of the 20th century?” the authors asked. This is the most important thing in this world: to raise children who will continue you and your people into eternity. Not everyone is capable of open protest and going to prison, but everyone is capable of this constructive work: raising children as Ukrainians.

O. Tykhy and V. Romaniuk also developed a code of conduct for political prisoners, which they strictly adhered to. In conclusion, the authors write: “There is no need to break the laws. It is enough to use the laws proclaimed by the Constitution of the USSR.”

On April 18, 1979, on the 17th day of another hunger strike, Tykhy suffered an internal gastric hemorrhage. (L. Lukianenko in his essay dates these events to October 1978). He suffered terribly for the last 18 hours. He was brought to the hospital with a blood pressure of 70/40. The camp warden, Major Nekrasov, said it was a simulation. But since at that time there was a lot of noise in the world about the first imprisoned members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, Mykola Rudenko and Oleksa Tykhy, it was unequivocally hinted to him that he could be certified for medical release if he wrote a repentant statement. There were such rare cases: based on the conclusion of a medical commission that a prisoner was chronically ill, a court would release him. Tykhy categorically rejected this proposal. Then they sent in the surgeon Skrynnik. Tykhy called it blackmail and refused to write anything. “You will live in agony, and not for long,” the Chekist surgeon promised him. He sewed up his stomach in the shape of an “hourglass”: food passed with great difficulty and with terrible pain. He came out from under the anesthesia a week later. Intestinal adhesions formed—another source of unbearable pain. The internal stitches of his wound came apart, and several hernias, the size of a bean or a walnut, formed along it. Tykhy again refused to write a penitent statement. On May 10, he developed peritonitis. They cut open his abdomen again and cleaned the abdominal cavity. The doctors submitted documents for his medical release, but they never left the hospital. Instead, on July 13, Tykhy was transported to a hospital in Nizhny Tagil in the Urals, although it was no different from the one in Mordovia. He was returned by transport back to Mordovia. The second wound (in the groin) healed only with the outer tissues, so his intestines protruded through a hernia the size of two fists. When he lay down, it would recede. He had to wear a truss (a hard bandage) to support it. But he was not exempted from work or from fulfilling his production quota.

In this state, in January-February 1980, Tykhy spent about 40 days in a punishment cell. He was punished for switching to political prisoner status. In particular, for not wearing the breastplate with his surname, for refusing slave labor, and for consistently observing the hunger strikes on October 30 (Day of the Soviet Political Prisoner), December 10 (Human Rights Day), and January 12 (Day of the Ukrainian Political Prisoner). His mustache became a byword: “They are trying to fit our Cossack lineage into their mold.” He would not shave it. For this, he was punished, and his mustache was clipped with a machine. Very few letters from him got through, but it was already known by then that Tykhy’s lung scars had opened.

During one hunger strike, when Oleksa learned that Vasyl Fedorenko, a man already severely damaged neurologically, had declared that he was supporting Oleksa, he asked to be taken to Fedorenko’s cell to tell him to stop the hunger strike. To everyone's surprise, they took him. He did not want others to suffer. His own ethical standards were so high that they sometimes seemed unattainable for a mortal man, yet he adhered to them.

From February 27 to March 1, 1980, along with the entire Sosnovka “contingent” (33 prisoners, one of whom died en route), Tykhy was transported to the village of Kuchino in Perm Oblast, where a new special-regimen camp had been opened.

When I arrived there on December 2, 1981, Tykhy was not in the zone. Sometime in the spring of 1982, we in cell 17 heard that Tykhy had been returned from the hospital and was in the adjacent cell 18. We could hear him vomiting. Vasyl Kurylo, who was taken out to clean the corridor, managed to talk to Oleksa and brought back grim news about his health (and Kurylo was a doctor): his stomach couldn't hold anything down, intestinal adhesions. (See: Vasyl Kurylo. A Meeting in Prison. A Political Prisoner's Memoirs of Oleksa Tykhy. – Newspaper “Neskorena Natsiya,” No. 13, 1992). Tykhy also had surgery for a duodenal ulcer.

Later, Tykhy was moved to our cell 17. He endured excruciating pain, but he would greet his interlocutor with a benevolent, yet deeply pained, smile. His light gray eyes shone in his well-proportioned, handsome face—a model Ukrainian, somewhat resembling Shevchenko. He spoke calmly and thoughtfully, never using swear words or jargon; his language was exemplary in its vocabulary and style, almost too correct—the way one writes, rather than speaks. At the same time, he was a man of iron will, rare tolerance, and exceptional patience. It was impossible to argue with him.

He read a great deal and reflected on what he read, initiating conversations on philosophical topics, especially on psychology and ethics. Mykhailo Horyn and Yuriy Lytvyn were worthy interlocutors for him, but they were soon separated into different cells. His favorite topic of conversation was pedagogy. He was meant to be an outstanding educator, but, as I said, instead of a university chair, he had hard labor. In this sense, we see in him a “lost force.” Tykhy clearly understood that the cause of national liberation required the sacrifice of the best. And this is the normal, natural behavior of a conscious person who respects himself and feels like a citizen of his homeland. When your lineage, your people are threatened, a citizen makes efforts to remove the threat, and even lays down his life for the community. But it is one thing to go into battle as part of an entire army, and quite another to rise up alone or with a small group of obsessives…

Vasyl Kurylo palpated Oleksa’s abdomen (he had sensitive fingers, because when his eyesight deteriorated, he worked as a masseur). He said nothing to Oleksa, but in his absence, he confessed to his cellmates that he suspected metastases. Oleksa said nothing about his torments. And he did not moan. Except in his sleep. And he would grind his teeth. He used to say: “He who has nothing to worry about, worries about his health.”

When severe pain overwhelmed Tykhy, he would drop his hateful work, lie on the floor or on a pile of cords, pull his knees to his chest, and endure silently, without a groan. It was probably easier for him that way. The guard would open the first door, bang his key on the bars, demanding that he get up and work, not violate the regime. But Tykhy would not respond: every word would be interpreted as “talking back,” which would be followed by punishment. And there were plenty of those already. Even that mustache. Every Sunday we were taken to the bathhouse, where the same procedure took place: “Tykhy, shave off the mustache.” Tykhy would silently clasp his hands behind his back, demonstrating that he would not do it, but would not resist either. He would sit on a stool. The bathhouse attendant, Hrytsko Kondratiuk, after clipping his head with a machine (Tykhy did not object to this), would silently hand the clippers to the guard, who would shave off the mustache. We told Oleksa more than once that perhaps it was not worth standing his ground on this, but he was stubborn: “If I yield in this today, tomorrow they will demand something else.” It was a matter of principle. One deviation from principle would put you in the ranks of the unprincipled, of whom there is no number or count.

But sometimes he would surprise me. We would go out for a walk in that small yard, and he, so wounded, would stand on his head in a corner and stay there for a long, long time. He said it was good for circulation (he used to practice yoga). But he was already walking hunched over. In that yard, he would mostly lie on a bench or even in the snow, with his knees pulled up to his chest. Or he would take a mouthful of water and sit for an hour with a book or at his work. That, he said, was also beneficial. A psychological exercise. To focus within himself. And to avoid empty, everyday chatter.

I subscribed to the magazine “Donbas” (it is bilingual), and in the first issue of 1983, an article by a certain Vadim Zuyev appeared, titled “Grimaces of Hypocrisy.” It was about “Zionists” like the future Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky and Lev Kopelev (who, by the way, had his Soviet citizenship restored on August 15, 1990, by the same decree as Mykola Rudenko). And woven into it were other “anti-Soviets” in the fields of “Zionism” and “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism.” That “Zionist” Kopelev, incidentally, had once supped on camp slop with Tykhy, which is why he spoke out in his defense in 1977. It is impossible to paraphrase Zuyev; he must be quoted:

“He (Kopelev. – V.O.) chose as the object of his slanderous attacks a Donetsk professor, a member of the Writers' Union, Illia Isaakovych Stebun, who had angrily testified as a witness at the trial of the Ukrainian nationalist Tykhy. A letter to the Donetsk scholar contained demagogic reasoning that revealed the anti-people essence of its author. Stebun’s attempt to fight back in the open press at some stage found no support. And again, the ray of public indignation did not single out the potential traitor from the general mass. One can only imagine how much harm was caused by the unjustifiably tolerant attitude toward these camouflaged enemies. And only when the logical development of the anti-people leaven in both Kopelev and Tykhy led them—via emigration to Israel—to the backwaters of Western Europe, when, following the cruel laws of betrayal, they signed a Zionist appeal in defense of the Polish counter-revolution, did it become clear to everyone what fierce enemies surrounded us.” (p. 88).

What vocabulary, what a style! “Anti-people,” “public indignation,” “traitor,” “unjustifiably tolerant attitude,” “camouflaged enemies,” “anti-people leaven,” “betrayal,” and, as a logical conclusion: “what fierce enemies surrounded us.” Enemies everywhere! So, deliver pre-emptive strikes against them. And so they killed, some say 40, others say all of 100 million “enemies of the people.” (See the article by Stéphane Courtois in “The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression.” Translated from French. Moscow: Tri Veka Istorii, 1999, p. 37). All to make the survivors happy… But, reader, I remind you, this was written not in 1937, but in 1983, in the magazine “Donbas,” No. 1, p. 88. It was precisely then that Andropov’s leadership was vehemently trying to prove to the world that it had no political prisoners—by exterminating us.

I gave Oleksa the magazine to read, advising him to respond, to say something like, here I am, in the “backwaters” of Eastern, not Western, Europe, and not in Israel. But he just waved his hand at it: “As soon as I start writing, the guards will take it away immediately. And even if I manage to write it, it won’t get past the KGB.”

Indeed, they took every piece of paper from him, while other prisoners managed to save something. You could be in the same cell, but have a different regimen. The only things that left the camp unhindered were sealed envelopes addressed to prosecutors. And they usually returned with an order from those defenders of rights: “Punish.”

When Oleksa was gone, I myself wrote a letter to the editor of “Donbas”—through the Donetsk Oblast prosecutor. Just to unburden my heart.

In the spring of 1983, Tykhy was released into the non-cell section of the camp. There he had to work as a stoker. He was unable to bring a wheelbarrow of coal or take out the slag; someone, most often Yevhen Polishchuk, would help him.

I saw Oleksa Tykhy for the last time on March 7, 1984. My cellmate, Balys Gajauskas, and I were taken out to clear snow near the walking yards, and the door was not closed. We saw Oleksa being led down the corridor. In a long, striped camp coat, he held his black bag in his hand. He was being transported. They later said he was taken to the Vsekhsvyatskaya station hospital, then to Perm. There they cut him open, saw that deadly metastases had destroyed his stomach, sewed him up, and left him to die. This Don Quixote of the 20th century, as Yevhen Sverstiuk called him, with the face of a European president, went to his death as his ancestors had gone to the stake.

Later, once free, people told me that in Perm on April 19, 1984, Oleksa was granted a brief, 40-minute visit with his first wife, Olga Oleksiivna Tykha from Moscow, and Volodymyr, his son from his second marriage (he lived in Kyiv). Tykhy was terribly thin: at a height of 178 cm, he already weighed 40 kg in 1981. His stomach could no longer accept anything. They led him in, supporting him by the arms; his fingernails were even falling off, but he was smiling, calm, and spiritually enlightened. He said that he forgave everyone, even his persecutors. “Remember the Sermon on the Mount,” he said as a farewell.

Sometime at the end of May, Levko Lukianenko received a letter from his wife, Nadiya Nykonivna, from Chernihiv. He sat over it for a long time, then stood up, pale, and began to pace the cell. He wrote to me on a piece of paper: “Oleksa Tykhy died on May 2.” He tore up the paper and threw it in the sink. I understood that this had been written in code in the letter, and I also remained silent. Then Levko sat down by the heating pipe and began to tap out this message in Morse code to Vasyl Stus. (We were all learning Morse code then—it was the fashion). Stus understood, but couldn’t believe it: he knocked on the wall three times, calling Levko over, and shouted through the food slot: “Did I understand correctly that Oleksa died?” And thus he “burned” Levko: he was put in the punishment cell for talking.

We later learned that Oleksa died not on the 2nd, but on May 5th or 6th: he had been left unattended and was found dead on the 6th. But in the meantime, Lukianenko had calculated the fortieth day after May 2 and proposed that we honor Oleksa Tykhy’s memory with a hunger strike, and on the 39th, 40th, and 41st days, with silence as well. We spoke only the most necessary things in whispers so the guards wouldn’t see or hear. The administration quickly figured out what was going on, identified the initiator, and threw him into the punishment cell again. That year we honored Yuriy Lytvyn and Valeriy Marchenko in the same way, and the next year, Vasyl Stus...

Oleksa Tykhy was buried in the “Severnoye” cemetery in Perm in the presence of his son Volodymyr. His son wanted to take his father’s body back to Ukraine, but he was told: “If you insist, the results of the bacteriological analysis might show hepatitis, and then you will never be able to take him.”

About the reburial of Tykhy, Lytvyn, and Stus on November 19, 1989, you can read in my article “The Return,” in the book “Uncensored Stus,” compiled by Bohdan Pidhirnyi (Ternopil, 2002), and you can see it in Stanislav Chernylevskyi’s film “A Black Candle on a Bright Road.”

But I must tell one more episode.

On September 1, 1990, I was at Donetsk University, where the public was for the first time honoring their countrymen Vasyl Stus and Oleksa Tykhy. Yevhen Sverstiuk, Stus’s son Dmytro, director Slavko Chernylevskyi, Rector Volodymyr Shevchenko, Donetsk Prosvita activist Mariya Oliynyk were there, and Ivan Drach and Dmytro Pavlychko happened to be visiting from Moscow. By noon, the auditorium was one-third full. The people there were lecturers, as the students had been sent to pick tomatoes. “Those empty seats,” said Yevhen Sverstiuk, “are the seats of trampled souls.” But the 79-year-old Professor Illia Stebun was there. I, unaware of his presence, read, without commentary, excerpts from his incriminating testimony at the trial of Oleksa Tykhy and Mykola Rudenko. I reminded everyone how in 1949, the Party Secretary of the Writers' Union, Mykola Rudenko, had defended Stebun from accusations of “cosmopolitanism.” Someone in the audience, as I was later told, touched his shoulder: “Who is this Stebun?” “That’s me,” Stebun said firmly. Then he was asked if it was true that he had written denunciations of Rylsky, Yanovsky, and Dovzhenko. “That list could be extended,” was the reply.

Sverstiuk sat at one end of the presidium table, and I at the other. Notes came from the audience, all from his side. As he later said, there was also a request to speak from Stebun. “Why didn’t you give him the floor? It would have been interesting to hear what he would have said.” “Whatever he might have said would have stunk.”

Stebun had only ceased to be head of the Department of Ukrainian Literature at the university in 1989, but he was still teaching.

What’s more, the lecturer Vadim Zuyev was also sitting in the hall. The very same one!

And one more thing. On January 27, 2002, Radio Liberty journalist Taras Marusyk invited me and Volodymyr Tykhy to participate in a radio program on the occasion of Oleksa Tykhy’s 75th birthday. I was asked there whether Oleksa Tykhy is properly honored in the independent Ukraine for which he died. Unfortunately, the authorities have other heroes. Recently, President L. Kuchma recognized Heroes of the Soviet Union, Heroes of Socialist Labor, and deputies of the Supreme Soviets of the USSR and the UkrSSR as persons with special merits before Ukraine. That is, the occupation administration and its most faithful servants. To be frank, the enemies and traitors of the Ukrainian people, who fought most fiercely against the independence of Ukraine. Pardon me. Of course, among those heroes and deputies, there were also people worthy of respect, but the main criterion for being honored during the Soviet era was not Ukrainian patriotism. In the USSR, Ukrainian patriots were called especially dangerous state criminals, especially dangerous recidivists.

True, on June 8, 2001, the President signed Decree No. 411 “On Lifelong State Personal Stipends for Citizens Who Were Persecuted for Human Rights Activities.” He appointed a whole 50 stipends of 100 hryvnias per month. At that time, there were still about 30,000 former political prisoners in Ukraine. Now, according to the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons, 23,000 remain. Almost all of them are living in poverty. Meanwhile, our KGB executioners receive decent pensions from the state of Ukraine, against which they fought so fiercely.

Oleksa Tykhy is honored by the public. On January 23, 1994, a scholarly conference was held in his memory in Druzhkivka, and a brochure of its materials was published. A charitable foundation named after Oleksa Tykhy was also established there, which holds annual competitions for the best works on human rights. The goal of the foundation is “the erection in the city of Druzhkivka of a monument to the outstanding Ukrainian human rights defender Oleksa Tykhy, and the publication of his works.” Its task is “the national-patriotic education of youth through the study and popularization of O. Tykhy’s works, his concept of the revival of national culture in the Donetsk region, and his human rights activities.”

Donbas. – 1991. – No. 1. – pp. 136–158; Molod Ukrayiny. – 1997. – No. 10 (17494). – January 28; Ukrayinske Slovo. – 2001. – No. 22. – May 31. Additions from 2004.

Published in:

Ovsienko, Vasyl. The Light of People: Memoirs and Publicistic Writings. In 2 books. Book I / Compiled by the author; Art and design by B.E. Zakharov. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2005. – pp. 262–308.

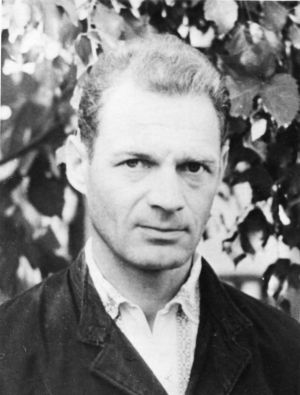

Photo:

Tykhyj Oleksa TYKHY.