THE LIGHT OF PEOPLE

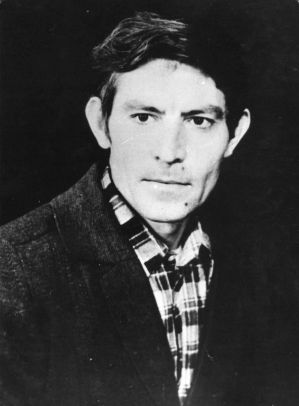

Memoirs of Vasyl Stus

MORDOVIA

February 6, 1976. Mordovia, the village of Ozerne, strict-regime colony ZhKh-385/17-A. The afternoon frost is 46 degrees below zero. The work detail assignment. We are standing in rows of five before the gates of the industrial zone. With a vile little smile, Lieutenant Ulevaty approaches:

“Citizen-convict, a hat should be tied under the chin or on top, not at the back. Come with me.”

But he leads me not to the headquarters, but to the storage room.

“Pack your things.”

“All of them? Where are you taking me?” The anxiety that always slumbers in a prisoner’s subconscious shoots sharply into my conscious mind.

Contrary to his usual habit, Ulevaty answers that I’m being taken to the hospital. I had long sought this, but had already lost hope. They lead me with my things to the guardhouse. But there, it turns out, the paddy wagon and the convoy haven’t arrived yet, so I have to wait in some nook. Behind a door, in the same corridor, is the visitation room. An older woman of Caucasian appearance and a girl so thin she seems translucent are led inside. A minute later, Paruyr Hayrikyan’s voice calls out from behind the door. He says they also pulled him from the ranks and just brought him for a visit with his mother and his sister, Lusine. Through a crack, he passes me some treats (it was chewing gum, which I had never seen before) and whispers:

“They’re hiding you from Vasyl Stus. He was brought to our camp today.”

From Vasyl Stus? So, after his surgery, he wasn't returned to "Number Three" in Barashevo, where they took him from last autumn, but to our 17-A. We knew that on the night of August 1–2, 1975, he had suffered a perforated stomach ulcer, meaning internal bleeding. They said that Stus had tried to leave the barracks at night but fell unconscious. Chornovil and someone else laid him on bedsheets and carried him to the guardhouse, demanding a doctor, while from the watchtower the guard shouted: “Halt, or I'll shoot!” The authorities, first and foremost, called not for a doctor, but for a convoy to take Stus to the hospital, which was within the same camp, a few dozen meters away, but behind a fence. Prisoner-orderlies carried Stus on a stretcher, accompanied by guards with machine guns and dogs. But no one attended to him there until morning. Soon Stus was returned to the camp, and then taken for transport. They said a new search method was used on him: you turn in all your belongings and clothes for inspection the evening before departure, take a temporary set, and get dressed in your own things the next day. After changing, Stus went out into the yard to talk with Viacheslav Chornovil.

“Wait, did you check what they gave you?”

They felt the pea coat and discovered a listening device the size of a five-kopek coin with two small wires. They smashed it so it couldn't be found by its signal and hid it. The next day, Stus was taken for transport, and Chornovil began to bargain with the administration:

“If you grant me the visit you illegally deprived me of, I’ll return your little toy.”

“Alright, I'll report it,” said a lieutenant who was not from the camp.

He returned some time later:

“You can keep it. If we need to, we’ll plant ten on you, too.”

And they did, later. In Yakutia, in exile, where they scared people away from him so much that there was no one to even talk to.

So, as we had heard, they had transported Stus to the Ivan Haass Central Hospital of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs in Leningrad (the prisoners simply called it “the Gaazy”), and after the surgery, for “higher operational considerations,” it was decided not to keep him with Chornovil and Vasyl Lisovyi in camp 3/5 near the hospital in Barashevo, but to bring him to this backwater, to Ozerne (Umor in Mordvin), where at that time there were only about 70 prisoners, among whom I was the only Ukrainian dissident. A pity that they are taking me away from here now…

I hadn’t met Stus when we were free, but we had already seen each other from a distance in the 19th camp, where I was until October 30, 1975. But Stus probably wouldn’t have remembered me. They brought him to our punishment cell (it was the only one for three camps) several times. On Thursdays, they would march the punishment cell inmates across the entire camp to the bathhouse. Those who could would go out to watch, hoping to exchange a word or pass along something to eat. Once, the youngest of the political prisoners, 19-year-old Lyubomyr Starosolsky, lit a cigarette and walked toward Vasyl, offering it to him. The guard snatched the cigarette and stomped it out. Vasyl later recalled this incident. To be honest, with my nature, I was not suited for such acts. I just stood among the people and admired his tall, almost majestic figure. I already knew several of his poems from Zoryan Popadiuk, who had carried them out in his memory from that same punishment cell. I had also read a few of his poems when I was free, knew he had a great essay about Pavlo Tychyna, “Phenomenon of the Age,” read his open letter in defense of the creative youth of Dnipropetrovsk, and heard about his speech on September 4, 1965, at the “Ukraina” cinema in defense of the 21 “Sixtiers” arrested on August 25... In a word, for me, a recent student and novice teacher, Vasyl Stus was one of the near-demigods, on the level of Ivan Svitlychny, Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Viacheslav Chornovil, Valentyn Moroz, Levko Lukianenko, Mykhailo Horyn, Ivan Kandyba… I had access to Ukrainian samvydav and was content with that, not seeking personal acquaintance with its authors, as it would have inevitably led to expulsion from the university, as happened before my eyes to my colleagues Mykola Rachuk, Nadiyka Kyrian, Mykola Vorobyov, Slavko Chernylevsky... Halia Palamarchuk barely held on.

The crackdown on the “Sixtiers” on January 12, 1972, I, then a fifth-year student of Ukrainian philology at Kyiv University, experienced as a personal tragedy. This crackdown put everyone in their place: some behind barbed wire, some into oblivion, while others, with a cry of “Glory to the CPSU!” heroically ran for the bushes, and still others—through broken spines to false repentance, and then to Shevchenko Prizes for, to use camp slang, “bitchy” little poems... Vasyl Stus received a non-standard sentence of 5 years in a strict-regime camp and 3 years of exile—the norm then was 7 plus 5. (For what “crimes”—anyone is now free to read the protest in the order of supervision by the Prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR M. O. Potebenko on the verdict in the case of V. Stus, published in the newspaper Literaturna Ukrayina on April 28, 1990).

Back in the 19th camp, I once noticed that the Lithuanians spoke of our Stus with particular respect. They explained why. It turns out that when the Lithuanian partisan Klemanskis, who was serving a 25-year sentence, died in Barashevo, Vasyl proposed honoring his memory with a minute of silence at the evening roll call. This, of course, was regarded as a “violation of the detention regime,” almost as organizing a rally—and Vasyl was sent for six months to the PKT (“cell-type facility”—one of the masterpieces of the ideologues of “developed socialism”: they didn’t have concentration camps, but “colonies,” “institutions”; they didn’t have guards, but “citizen-controllers”; they didn’t have political prisoners, but “especially dangerous state criminals”...)

All this ran through my mind as I waited for the paddy wagon. So, they’re hiding me from Stus’s “corrupting influence”… I wait for about four hours, listening in that nook to all the sounds—when you’re locked up, you see almost nothing, so your hearing becomes the main source of information about the surrounding world. I hear the voice of the unit chief, Captain Oleksandr Zinenko. The door opens:

“There’s no transport and no convoy. Go back to the camp.”

I gladly grab my backpack, but a phone call—and Zinenko stops me. Half an hour later, they finally take me in a paddy wagon to the Shale station, put me on a railcar like a great lord, and around midnight deliver me to the hospital in the village of Barashevo, which is one of the sections of colony ZhKh-385/3. Some escort, probably a KGB officer, kept asking me on the way if I was cold, how I felt. Strange. But I didn’t have to wonder for long: at the guardhouse, I peeked at the accompanying document: “Sentenced Ovsienko V. V. is being directed to the surgical department…” and corrected: “Psych.” A chill ran through me.

“So where are you headed, with what illness?”

“Probably the surgical department, because the illness is, as the gypsy said, the worst kind: you can’t look at it yourself, and you can’t show it to another—hemorrhoids.”

“Well, alright, there are no beds in surgery. It's Saturday now, there are no doctors, so go to the therapeutic ward, and they’ll sort it out on Monday.”

…They sorted me out on Tuesday, but until then and after, all sorts of thoughts had crossed my mind. It was the height of Soviet punitive psychiatry. For about a month and a half after my arrest (March 5, 1973), I tried not to give the investigation any testimony, only explaining a few things. Then the Kyiv region KGB investigator Mykola Pavlovych Tsimokh told me the sacrosanct, carefully weighed words: “Some people here have doubts about your mental competence. We’ll have to conduct a psychiatric evaluation.” A few days later, he quoted some things from my notebooks. They were mostly drafts for various literary ideas—who in their youth didn’t want to play with words? But the most dangerous were the entries from the autumn of 1972. After the January events, after the arrest of my dearest friends, particularly Vasyl Lisovyi, after losing hope of entering graduate school, after my own heartaches, I had fallen into despair and wrote that it wasn’t worth living in this world. And I began to imagine how it might happen. Feeling and thought grew into words—and I saw a literary work budding from it. That’s probably how things get written. But for the investigation, this last part became grounds for blackmail: this, they said, is the raving of a madman. And I already knew that Borys Kovhar, Leonid Plyushch, and Mykola Plakhotniuk had been thrown into a psychiatric hospital for refusing to testify; I knew why Mykola Kholodnyi had written his shameful “recantation”… A white wall of fear rose before me: to end up in a psychiatric hospital at 24, where they would turn you into a human-like animal, seemed more terrifying than death. And I began to give in. I said from whom I had received samvydav and to whom I had given it to read. No one was imprisoned because of me, but some of my friends suffered. When I later thought about why so much misfortune had befallen me, I came to the conclusion: for this sin. People seemed to have forgiven me, but only the Lord Himself can determine the measure of sin and penance: maybe I still owe a million years of purgatory for that sin?

At the time, at the price of sin—confession and a deceitful admission of guilt—I managed to get out of trouble and my soul was revived upon entering the favorable environment of political prisoners, where I was not the only one of my kind. But now, in February 1976, I was once again gripped by fear at the prospect of ending up in that 12th block, the one behind the fence. The horror stories told about it were not made up…

It wasn’t until a month later that the surgeon Skrynnyk somewhat dispelled my fear when I cautiously asked for an explanation.

“I didn't even pay attention to that referral. Your Antipov wrote that so they wouldn't send you back to Ozerne, because there really were no beds in surgery then. But they always take you in the psychiatric ward!”

Antipov was the head of the medical unit of the 17th colony. Stus later called him Antypko—there is such a little devil in Ukrainian mythology. That's how easily one could end up in a madhouse back then, where it was useless to prove you weren't a “schizo.” And at that time, everyone accused of “conducting anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” was sent for a psychiatric evaluation, including myself—I spent 18 days in the “Pavlivka” hospital.

We started talking with Skrynnyk about Stus. Skrynnyk had a reputation here as a sensitive man and a good surgeon, thanks to his ample practice and the lack of accountability for failures. He was displeased that Stus had supposedly refused to go under his knife. The memory of the Russian dissident Yury Galanskov, who died in 1972 as a result of a carelessly performed operation and lack of care, was still fresh.

But it later turned out that no one had even asked Stus about his wishes, and his road to “the Gaazy” had not been a direct one…

I was returned from the hospital to the 17th camp only on May 8, 1976. I walk into my section in the same felt boots I had left in—Stus is not here. In the second section, a lanky man in a white shirt lies on a bunk with a book in his hands. He looks at me with penetrating dark-brown eyes and says:

“Thank God… I've been missing you.”

“How so, you don’t know me?”

“I figured it out. It’s hard for me here with this international crowd without a single kindred spirit.”

He put his book aside, got dressed, and we went out to the “orbit”—a twin path along the edge of our small camp, alongside the “forbidden zone” (it's harder for informers to overhear conversations when you're walking).

Vasyl told me that they had taken him to “the Gaazy” via the Kyiv KGB, thinking that in his condition he would be more compliant and perhaps write a “recantation.” The impression from that trip to Ukraine was reflected in this poem, which was probably composed then, because, God as my witness, Vasyl told it to me in almost these exact words:

What an unbearable native foreign land…

This ruin of paradise, a temple defiled.

You have returned. But the land does not return,

For it, a stone darkness is a coffin…

This was about Kyiv, devastated by the arrests of 1972. He told me that on the day of his arrival, his wife Valentyna was detained at work, and their 9-year-old son Dmytro was summoned to the juvenile department of the police, even though they had no idea he was coming. Then his almost 80-year-old mother came from Donetsk for a visit. But they didn't grant a visit to anyone:

How hard to arrive and not

To see. How hard, not—to meet…

Carefully, Kyiv, you hid me

In black chambers, vaults, and crypts…

Later, reading this poem, I vividly felt all those circumstances, because I myself had spent over 13 months in those chambers at 33 Volodymyrska Street. A deathly silence: the guards walk the corridor in slippers, a carpet laid on the floor, they peer into the peephole every minute. You are only allowed to lie in a way that your face is visible. You can only cover your eyes from the light with a handkerchief, folded into a strip a quarter of its width. If you need to be taken to the investigator, the “feeding hatch” (a hole in the door for passing food) opens and the guard whispers:

“To the ‘O’.”

You must answer: “Ovsiyenko.” This is so your cellmate doesn't go in your place. Leading you with your hands behind your back through the corridor and yard to the investigation building, the guard loudly snaps his fingers. And some click with their mouths—that’s professional skill! Because a non-professional claps his hands or jingles his keys: hide, everyone, an especially dangerous criminal is being led through! In all 13 months, I saw a tall man in the corridor only once—could it have been Stus? They shoved me into an empty cell, an argument broke out between the guards who had misunderstood each other. An extraordinary event…

Further in this poem, there was a somewhat desperate note, which Vasyl later rejected:

How hard to arrive and to leave,

Suppressing a meager tear of insult!

Rejoice, you hypocrites and icon-smearers,

That I have neither hope nor goal.

But then came the angry lines:

But I myself exist, and my chest’s pain exists,

And there is a tear that sears right through

The stone wall, where a flower blooms

In three screams of color, in three screams of madness.

Vasyl was very pleased with this “flower” as a good find, when he read me this poem a few years later in the Urals. He thundered in his powerful voice, and you were pierced by his pain, because it was your pain too:

Your soul collapsed right here,

Half of your chest is gone,

For the charm of your Ukraine is fading

And a black octopus sucks at your ailing heart.

After this poem, Vasyl would always read another, about his departure from Ukraine. There, in the KGB, he had categorically refused to speak with the KGB officers, and had a sharp exchange with the prosecutor—and they put him on a transport. Imagine, reader—I don’t have to imagine, for I was transported like that twice myself: they put handcuffs on you in the prison yard, lock you in the “box” of a paddy wagon, where you sit squeezed by metal on all sides, bring you to Boryspil airport, where the roar of a plane rolls over the roar, they position guards with machine guns and dogs and lead you to the plane's ramp, you have a step to take, you look around for someone to say goodbye to, because maybe you will never see Ukraine again, and all you see is this convoy and somewhere on the horizon, poplar trees:

“Kraykil!”—a cry from the left—

“Intercept him! Intercept!”

…Ukraine! Be happy!

Sleep-poplar! Farewell!

…The thunder’s great masses come crashing

headlong down on you…

Be damned, you aerodromes!

Turn to ash in your hundred sorrows!

…The blood surged… To stay behind!..

To remain!.. At the edge!..

…We'll dance yet, brother-sir,

On an unsheathed knife.

You feel your blood surge toward your native land, but they grab you under the arms, lead you to the tail of the plane, soldiers sit on both sides, an officer in front. Only then do they let the passengers on. They give you sidelong glances: look what kind of murderer they're transporting! But they are transporting a poet, tortured for a word of truth. The soldier shyly covers your handcuffs with your hat. If you move your hands a little, they—click!—tighten. Your hands turn blue, and you don’t want to move. They lead you off the plane last and remove the handcuffs only in the paddy wagon.

Stus's poem “Today, today the plane departs…” is probably about these same travels.

That is how they brought Vasyl from Moscow to Kyiv (from Mordovia to Moscow by a “Stolypin” prisoner car), and that is how they took him back to Moscow. He said he was in transit for about two weeks:

“By God’s grace I didn't perish on the road on that bread and herring. And what a day they chose for the surgery—December 10th…”

“And what momentous dates someone has marked for me…”

Indeed, Vasyl came into this world on the very Christmas of the year of our Lord 1938. His mother was afraid to register his birth on the seventh of January, so she registered it as the sixth. Once, in the last year of his life, in the Urals, in Kuchino, in my presence, Vasyl asked the deeply religious self-taught theologian, old Semen Pokutnyk (Skalych):

“What does it mean for a man to be born on such a great holiday?”

“It is an additional grace from God, a happiness,” said the old man. “But to whom much is given, much will be required.”

And so it was, for he was arrested on the Orthodox New Year, January 12, 1972. The perforated ulcer occurred just as the signing of the Final Act of the Helsinki Conference was being solemnly read on the radio—August 2, 1975. He was operated on Human Rights Day—December 10, 1975. And he died on a memorable date: on September 5, 1918, the Sovnarkom decree on the Red Terror was signed—it lasted 73 years. At that time, Vasyl did not yet know that the 20th anniversary of his speech at the “Ukraina” cinema (September 4, 1965) in defense of the arrested “Sixtiers” would become the day of his death. And it happened exactly one year after the death of Yuriy Lytvyn (September 4, 1984). Such “momentous dates.”

What lay beyond death, I came to know,

the full force of that mysterious action,

all the gloom of heavens and the mire of the restless earth.

And it is hard to live, buttressing with this knowledge

my dwelling, rotted to a wasteland…

The operation was severe: they left Vasyl with only a quarter of his stomach, as the ulcer was of a wandering kind. To write such otherworldly poems—one had to have been t h e r e. Now, the poem “How good it is that I do not fear death…” is often quoted. They say that everyone is afraid, and whoever says they aren’t is lying. Fear is a natural reaction of a living organism to danger. But courage lies in how a man is able to overcome his fear. Vasyl, it seems, overcame it. And so, it was decided to tighten his regime.

This 17-A camp was also a strict-regime one, but the regime in it was far stricter than in camps 3/5 and 19. And quite famous, to be sure. It was here that Valentyn Moroz wrote his “Report from the Beria Reserve.” Daniel and Sinyavsky were imprisoned here. Viacheslav Chornovil began his term here. Not long ago, they had sent the Latvian Gunars Rode, the Russian Yevgeny Pashnin, the Moscow democrat Kronid Lyubarsky, and the Ukrainian Dmytro Kvetsko to the Vladimir Prison from here, and the day before my arrival—the fine fellow from Sambir, Zoryan Popadiuk. On October 30, 1975, they settled me in his well-lived-in spot, which was now surrounded by informers. For a sharp conversation with KGB agents and “representatives of the Ukrainian public”—such people visited us from time to time.

Now Vasyl and I would be here together… Naturally, in our subsequent interactions, we were not equal partners, but Vasyl, it seems to me, always treated me with particular kindness. Now I understand why: it was a credit extended to my youth. The older simply love the younger, and so they forgive them much, and are even inclined to praise them, remembering themselves at that age.

On one of the very first days of our acquaintance, Vasyl and I went behind an abandoned barrack to a rosehip bush and a patch of ground dug up for a flowerbed. I knew that on this spot Mykhailo Mykhailovych Soroka had died, a participant in the Ukrainian underground, a prisoner of Polish, Stalinist, Khrushchev-era, and Brezhnev-era concentration camps. It was he who, upon his release in the late forties, received a mission from the Main Command of the UPA to gather data on the locations of concentration camps and the conditions of political prisoners. Soroka fulfilled the task, but for this, he was imprisoned for another 25 years. However, his data was used by the US government to expose the former Prosecutor General of the USSR, Vyshinsky, who had come to America to represent the USSR at the UN. They said that Vyshinsky, upon hearing this, gave up the ghost.

Mykhailo Soroka was one of the organizers of the political prisoners' uprising in the northern camps (Kengir, 1954). A legendary figure, the greatest authority among Ukrainian prisoners for a quarter of a century. Memoirs have been written about him abroad, even in Japan (for who hasn't been imprisoned in Soviet concentration camps!), but here—nothing. (A book has now been published: Lesia Bondaruk. Mykhailo Soroka. Drohobych: Vidrodzhennia, 2001. - 296 p.). No less legendary was the figure of his wife, Kateryna Zarytska (she headed the UPA's medical service). After torture, she received a 25-year prison sentence, which she served together with Darka Husyak and Halyna Didyk. Only in the last years of their imprisonment did these women serve time in Mordovian concentration camps, including Kateryna, who for a time was in this very 17th camp, but in the women's section. The camps were separated only by a few wire and board fences. Soroka would secretly climb onto some elevation and sometimes see his wife. Many people told me about these people with admiration as some of the best ever born of a Kozak mother. But let those who knew them personally write about them. No one will do it for them.

So, it was along this path on June 16, 1971, that Mykhailo Soroka was walking with Mykhailo Horyn. Here, Horyn went on ahead, as Soroka usually descended the hill second, so it wouldn't be obvious that his heart was aching... Here he sat down, feeling a sudden sharp pain, while Horyn walked on, talking about something. He looked back, rushed to help him lie down on the grass, ran for a doctor, but there was only a prisoner-orderly who knew nothing of medicine. Instead of giving the heart patient medicine, seating him against a wall, and leaving him in peace, he began to perform artificial respiration. Only a sorrowful tear rolled from Mykhailo Soroka's eye... This flowerbed is like his grave, for who knows where he was buried. (He was buried in Barashevo. From there, his ashes were transported to Lviv and on September 28, 1992, reburied in the Lychakiv Cemetery, along with the transported ashes of his wife, Kateryna Zarytska).

Vasyl Stus, as soon as it warmed up, dug up the flowerbed. Seeds of marigolds and stocks were found. We began to care for the flowers, and by God's will and our efforts, they bloomed profusely, delighting our eyes and souls. But Zinenko was informed that the Ukrainians had created a sanctuary for themselves here (we were joined by the 25-year-term insurgents Ivan Chapurda and Roman Semenyuk, who was transferred here from the 19th). So Zinenko ordered two “stooges,” Kononenko and Islamov, to uproot the rosehip bush while we were at work, tear the bush to pieces, and plant it opposite the headquarters, and to trample the flowers. It was painful to watch such desecration.

However, even after this, shoots sprouted in the flowerbed; the bush would have revived. And some of the flowers recovered. But I had to tend to them without Vasyl, as he was periodically in the punishment cell, and it was impossible to protect it from desecration. Everyone here who could pass information to the outside world about our existence is deprived of visits.

...Two barracks, one of which is already abandoned. Headquarters and a dining hall. Beyond the gates—the industrial zone, where we sew work gloves. In the middle of the camp—a depression full of rainwater. Here, they say, executed prisoners are buried, which is why it has sunk. In the camps, when they started any construction, they often found human bones. Ivan Palamarchuk, convicted on charges of collaborating with the Germans, showed me a small wood behind the camp:

“My father lies there. And in Barashevo, where the hospital is, there are eight thousand nuns. The burial site was planted with pine trees.”

This poem must be about the 17th camp:

Winter. A fence and a black cat

on the white snow.

And a raven among the willow boughs

bends into an arc.

Two hunched pines

feel a mortal cramp.

All around are the dead, and their dreams

stand, like pines, erect.

Two gates, sunk into the earth, darkness.

The watch bell tolls.

And there is no breath, no relief

from the mourners, from the phantoms.

Winter. A fence. And a black post.

A net of spikes.

And a golden gallop of horses.

A fiery thunder of hooves.

There were only about 70 prisoners left in this camp, so the kitchen was “downsized.” Leftovers from another unit are brought in thermoses by a mare named Masha. Though, it seems, it was already a horse that had inherited the name of its deceased predecessor. “Masha the mare” knows her route from camp to camp by heart. They open the gates for her without asking her name, article, or sentence. With a sideways glance, as the cart moves, she turns around in the yard and stops right by the building where the kitchen used to be. A handful of grass or some leftovers await her there. The news flies around the camp: “Masha has arrived!” You take a spoon, a ration of bread, and go to slurp the thin soup. The zeks say: “Masha is our joy.” And Valeriy Graur, who had a penchant for aphorisms, once proclaimed: “Masha is the best person in the administration.”

The administration of the unit consists of Captain Oleksandr Zinenko, who looks ready to burst out of his uniform, and his assistant, Lieutenant Ulevaty, who likes to stop a zek and, while talking, rummage through his pockets. We rarely see the colony chief and his deputies: they don't get involved in “politics,” their three thousand criminals are enough for them.

The majority of the prisoners were older men, serving time for wartime offenses. For collaboration with the Germans, for partisan struggle against the Soviet occupation—Lithuanians, Estonians, Latvians. And, of course, Belarusians and Ukrainians. There were about 15 dissidents.

Here is Ivan Andriyovych Chapurda, a man of good peasant stock from the Chortkiv district in the Ternopil region (I have now forgotten the name of the village, but after my release, I wrote a letter to his sons). He feeds pigeons from his meager ration and mumbles something to them. Lieutenant Ulevaty, saving the people's property, put the old man in the punishment cell for 15 days. There he fell ill and soon died in the hospital in his 23rd year of imprisonment. Vasyl Stus mentions him in his now-famous letter to his son Dmytro dated April 25, 1979. That he would like to live like that old man, so that pigeons would land on his shoulders.

In the harsh winter of early 1976, pigeons and sparrows indeed flew right into our hands, begging for food. They would fall in mid-flight. We picked them up and warmed them in the workshop. This enraged the authorities. A guard with the characteristic surname Kyshka (Guts) tells how they brought the zeks, they stand in the enclosure, stamping their feet in the cold. “And I tell them: my geese walk barefoot all winter, and it's nothing. Ha-ha-ha!” What does such a man care about a pigeon. I am sure this poem is about Ivan Chapurda:

If you had, o pigeons,

even a little heart—you would on your wings

take him to you and carry him over

to Ukraine, which has long been pining for him.

To you he will raise a kind hand

and call out—generously and invitingly:

“Come to me—here is food and drink for you:

crumbs on the path, in a shard—water.

Come now, little one, who on your sore leg

so often limps—let me

pull the splinter from your paw, right from my lips

I will feed you, you yellow-beaked thing,

and let you fly into the sky from my hand.

…That God of birds, and of early spring, and clouds,

and of the rustling young greenery,

rejuvenated in a hundred streams

of heavenly spring—He sees it all,

and hastens life, and hastens the resilient flight

to eternity, to the eternal abyss.

Here is the Lithuanian Petras Paulaitis, tall in stature and spirit. He washes dishes in the kitchen. He is a former Lithuanian ambassador to Italy, Spain, and Portugal. During the German occupation, he edited a Lithuanian newspaper. The Germans closed it, and the editor had to go underground. However, the red “liberators” accused him of collaborating with the German occupiers and gave him 25 years. They released him in 1956, but, it turned out, “by mistake”—a few months later they gave him another 25.

August Reingold. Doctor of Law from the University of Tartu. For some reason I can't recall, Lieutenant Ulevaty said to Reingold: “You and I will yet meet on a narrow path.” “If we meet, I will aim carefully,” the Estonian replied slowly but clearly, articulating the Russian words. The verdict: “Threatened a superior.” 15 days in the punishment cell. Since Reingold was already disabled and didn't sew gloves, there was no point wasting thin soup on him. This meant he was given the punishment cell without being sent to work, and for such prisoners, hot food is given once every two days. Without fats or sugar. And 400 grams of bread, boiling water, and salt every day. After the New Year, he and I were in the punishment cell together in the 19th camp. I was the same kind of “terrorist”: I told Ulevaty that he would not escape justice. Also “threatened a superior.” And also “failed to show up for political instruction, and arrived 5 minutes before the end.” I had accidentally stayed too long with old Volodymyr Kaznovsky.

Old Volodymyr—towering, emaciated, with a huge bald skull, leaning on a crutch and groaning with every breath, makes his journey to the latrine. He covers the 50-meter path and back in half an hour. He is kept in the medical unit. Every evening he crawls out onto the porch to listen to the news, which always began like this: “This is Moscow. We are broadcasting the latest news. Today, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, comrade Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev…” The old man waits for someone to come and talk. He said little about himself, fearing to worsen his situation. But he wanted at least to die free. Under the Germans, he had served in the Ukrainian police, helping the insurgents. He was imprisoned sometime in 1957. Vasyl and I spent a lot of effort to get him to agree to have his name included in our lists of political prisoners, which were circulated in the West. And—a miracle—it turned out the old man had a son abroad! He began to demand his medical certification for release. There is such a form of release: a medical commission declares a prisoner chronically ill, then a court can release him early. But few of those certified ever made it home, and those who did, did not live long. The calculation was reliable. Some even began to fear certification: here in the camp, you could still linger on, but after enduring the shock, you wouldn't be able to adapt to the new conditions. This was precisely the fate that befell Kaznovsky: he reached his sister in Yaremche and died, already holding a plane ticket to go abroad (or perhaps on the plane itself).

Roman Semenyuk, born in 1928. A peasant boy from near Sokal was conscripted into the Soviet Army in 1949, but they discovered he had collaborated with the insurgents. 25 years of imprisonment. In the early 60s, he escaped with Anton Oliynyk. Anton was shot, with “newly discovered crimes” attributed to him, and Roman was given an additional 3 years of prison on top of his 25. Mr. Roman was one of the few prisoners of the old guard who openly sided with the dissidents and took part in our protest actions.

Paruyr Hayrikyan. Almost my age, he had already become the recognized leader of the National United Party of Armenia. Stus was the first to join in observing April 24 with a hunger strike in memory of the victims of the 1915 Armenian genocide—thus was born the idea of admitting non-Armenians as sympathizing members of the party. Vasyl sincerely loved Paruyr, as he did all the Armenians he knew in other camps, and they reciprocated his feelings. Paruyr is exceptionally talented precisely as a politician, as a public figure. This was already evident in how he could organize actions, what complex combinations he played out to trap an informer or pass information to the outside world. (See: Mikhail Kheyfets. Selected Works. In three volumes. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. – Kharkiv: Folio, 2000. Essay “The POW Secretary” in vol. 3, pp. 198–282). Moreover, he is a poet and a singer. How mournfully and penetratingly his voice echoed in the punishment cell corridor when we were there at the same time. Even the guards listened, mesmerized, and did not shout.

Vitaliy Lysenko and Yuriy Butenko—these guys aroused some distrust, as they were accused of espionage, so it was difficult for them to defend themselves against the administration, and they had to be quieter. However, when it came to defending Vasyl, they participated in the protests.

Vasyl loved to chat with Ivan Musiyovych Palamarchuk. He was well-versed in music. The accusation of collaborating with the German occupiers did not give such people the opportunity for self-defense in the political camps. They worked silently, waiting for the end of their 25- or 15-year terms. Knowing they were defenseless, the administration tried to use them against us as informers, and some went along with it. But this snitching was repugnant to almost everyone, even to people like our brigadier, Prykmeta.

I will speak of Mikhail Kheyfets separately. (See also the essay “The Tortured Union”).

There, in the 17th camp, Stus let me read some of his poems, among which the impression of this one remains memorable:

Allow me today, around six o’clock,

When evening falls all around

and the transport rumbles at rush hour—

suddenly, out of longing, out of the stifling sky,

out of oblivion, out of boundless separation,

intoxicated by long vexation,

I will fall onto Brest-Lytovsky Prospekt,

onto that estranged Fourth Clearing,

where only the mocking roar of the highway

will tell me that the fearful thumping of my heart

beats in unison with my native land.

All these are Kyiv realities that surfaced in memory: somewhere there, his wife Valentyna struggles with hardship, somewhere there, his son Dmytro, the house at 62 Lvivska Street, with its “paradisiacal”—because it is home—gate. All of that has now been renamed, destroyed (where their house was, there is now a road across from the “Dachna” bus station leading to the Ring Road), but it remains a poetic image that wrings a tear from the heart, as if it were about your own pain:

From the human anthill, from separation

I will tear out the memory of long-forgotten days,

that have become a dream and a sorrowful reality,

like wounds, completely covered with scars.

You do not object, my love, you do not object?

Oh, do not be afraid: among the human crowd

I will disappear, dissolve, be lost,

so that your frightened gaze, by chance,

does not plunge into my heart like a knife.

So do not be terrified—I will pass like a shadow…

I will touch with a burnt wing, with lips

scorched—or with the corner of my mouth

to partake of your sorrow.

So do not be terrified: I will pass like a shadow.

And then, when like a pensive little girl,

who has wronged the entire world

with the childlike purity of her gaze

and the helplessness of her commanding chastity,

you emerge unhurriedly from the tram

and cross the road, to dive

into the gnarled dusk of the vigilant pines,—

then I will tear my heart out for you,

wounding myself on the thorny thickets,

watching your trail, which from the edge

of my soul stretched across the whole world.

I will follow in your steps, like a feral dog,

hiding in the hollows of your footsteps

my shame, my fear, my offense,

and joy, and passion, and fierce pain…

I will be but a shadow of a shadow,

I will fall from my face, from experience, from years,

as a single, sinewy leaf of my heart

I will roll in the wind of my own storms.

…Here is our porch. You are already at the door.

You pressed the bell and so lightly

opened the heavy paradisiacal gate.

Our son called out. I should have shouted. But

I had no strength to raise my voice.

And then—the painfully familiar entourage of our camp:

…The dream broke. On the wall swayed

a road bisected by a noose

to my yard. And the barbed wire,

swollen with night, ran like spiders

across the frozen wall. A dull ceiling lamp

stirred the slop of the night. The dawn

hung over the palisade. A screeching

bell, like a corkscrew, uncorked from the bottle of slumber

the mire of a new day…

…To die on the road of return

is too sweet for the Lord

not to have placed it as a headrest in our fate.

“The mire of a new day…” Reveille, roll call, thin soup, work detail, sewing gloves, thin soup, work, roll call, thin soup… You get a little relief in the evening. You can read for 2–3 hours, chat with people. But a loudspeaker blares over it all. Both in the section and outside. Nowhere to concentrate. And to write—absolutely nowhere. A movie, something like “Lenin in October”—once a month. And rare letters:

…where the greatest of rewards—are letters,

for our exodus, for our arrival…

You have the right to write two letters a month, and receive them without limit, but they find “forbidden information” in them and confiscate them. Both your letters and those to you. The information famine is no easier for an intellectual to bear than the lack of food. And in the radio and the press—emptiness.

Ukraine is far away—no one will hear!..

And yet, even there, there were bright hours. There was the joy of communion with people and, obviously, the secret solace of creativity, though those poems were raw pain. I am especially struck by the details of our zek life, filtered through the poet’s aching heart. Vasyl’s greatest concern was to protect them. It was here that real dramas unfolded, here that the tragedy of his life lay.

Shortly after my return from the hospital, Vasyl was accused of some triviality and put in the punishment cell for 15 days. There is no way to pass on this information to the outside world, so there is no point in showing solidarity with Vasyl or starting a protest action: if the world doesn’t know about it, the demand will not be met. But it’s also impossible not to protest. The first idea is a hunger strike. But that is too difficult and ineffective. Then Roman Semenyuk said he was starting a partial hunger strike: refusing breakfast, lunch, or dinner. The idea was well-received: without suffering too much, we would still demonstrate our solidarity. Absolutely all the dissidents in the camp took part in the action: the Jew Mikhail Kheyfets, the Romanian Valeriy Graur, the Russians Vladimir Kuzyukin and Pyotr Sartakov, the Ukrainians Viktor Lysenko and Yuriy Butenko, the Armenian Paruyr Hayrikyan, as well as Roman Semenyuk and I. Zinenko was furious:

“They eat like horses, and they say they’re on a hunger strike.”

This went on for 15 days. Of course, we didn’t get Vasyl out of the punishment cell, but we still felt like human beings. When I later, somewhat sheepishly, told Vasyl about this action, he consoled me:

“Vasyl, even if you ate two rations plus a hospital ration 5-B, and on top of that the camp store provisions—it would still be a partial hunger strike.”

Vasyl returned from the punishment cell in a terrible state. I come back from work for lunch—he is in the yard. Seeing me, he suddenly put on a stern expression. What’s wrong with him, I wonder.

“Vasyl, please accept my condolences on the death of your father.”

His heart responded to everyone’s misfortune. My father had died back on May 8, but the news only reached me on the 21st, when Stus was in the punishment cell. Later, we held a forty-day memorial for my father: we made a salad from weeds, dressed it with oil, brewed tea… By the way, those weeds helped us a lot, because our food was potatoes and groats, no vitamins.

We began to think about how to ease Vasyl's situation. And someone with more experience recalled that one could apply to be certified as disabled for a certain period. This provided the opportunity to work not 8, but 6 hours and to sew 3/4 of the glove quota, as well as to receive slightly better food. Swallowing his pride, Vasyl wrote such a request in order to snatch an extra two hours for himself. But to be certified as disabled, one had to go to the hospital in Barashevo. As he was getting ready, Vasyl took with him a volume by some philosopher—dense, compact reading, so as not to overly irritate the authorities. And that’s when the incident occurred. Zinenko would not allow him to take the book: “You are going for treatment, not for studying.” This is one form of torment. The regime in the hospital is much milder, but there is absolutely nothing to do there: books are not allowed, except rarely for a few. You walk around there, bored to death between the barracks and the morgue, looking at the ready stack of coffins, which greatly contributes to a speedy recovery…

So they don’t give Vasyl the volume. Vasyl refuses to go without the book. But the order is already issued, the convoy has arrived. They twist Vasyl’s arms, put him in handcuffs, and shove him into the “box”—a cell in the paddy wagon, approximately 120x60x60 cm. In the hospital, Vasyl wrote a statement in which he called Zinenko a fascist. I don't think it greatly offended an ox like Zinenko, but it was sufficient grounds for further retaliation. Vasyl was granted disability status, but a few days after his return to the 17th camp, Zinenko found a reason to throw Stus into the punishment cell. So much for Vasyl’s disability status…

It seems that this time we managed to report it to the outside world. And I was hoping for a visit on July 11. To my surprise, I wasn’t deprived of it. My mother and sister had already set off on their journey, gone to the bus, but they were caught up by my telegram telling them not to leave. I myself was collected for transport on July 9. On the way, I understood that it was to Kyiv, “to have my brain washed.” The “higher operational considerations” were probably this: Ovsiyenko’s prison term is ending soon, he was not firm at his trial, he pleaded guilty, now his father has died, he recently had an operation—so wouldn’t he write a recantation, wouldn’t he badmouth his Mordovian comrades in the press? They could even release him a few months early and thus finally break him and cut him off from like-minded people. True, he is trying to resist, he hasn't spoken to the KGB for almost a year, but here we’ll bring his relatives to him, send his former teachers and university professors… The plan failed. In Kyiv, on August 20, I submitted a statement that my admission of guilt at the trial was a forced consequence of psychiatric terror. So, without any special honors (not by plane, but by a regular prisoner transport), I was returned to my dear Mordovia and on September 11—the very day of Mao Zedong’s death—I arrived at the well-known to me 19th camp. It’s much easier here than in the 17th.

Immediately, another piece of news: it turns out that 17-A as a political camp no longer exists. It has been given over to criminals, and our “contingent” has been dispersed to other camps in Mordovia, some to the Urals. And Stus (though he is currently in the hospital), Kheyfets, Lysenko, Semenyuk, and Kuzyukin ended up in the 19th. Hayrikyan exposed the latter as an informer, so he wasn't even allowed into the camp—he was pardoned.

Before I continue the story, I must tell about Mikhail Kheyfets, a Russian-speaking Jewish writer from Leningrad. He is already over 40. A Russian language teacher who found it difficult to be disingenuous with his students, so he took up literary work for hire, in particular, ghostwriting a book for some general, who then removed the note “Literary transcription by M. Kheyfets.” He knew the poet Joseph Brodsky well and wrote a long article about his work, defining him as a poet of genius. Brodsky served 5 years of exile and went abroad. With a 9th-grade Soviet education, he became a university professor there… Kheyfets read in Brodsky’s poems what was only hinted at: the Czechoslovak events of 1968, and he clarified the perspective on them. (See: Mikhail Kheyfets. Selected Works. In three volumes. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. – Kharkiv: Folio, 2000. Essay “Joseph Brodsky and Our Generation” in vol. 2, pp. 198–217). A few conversations, a few notes—and there you have it, a sentence: 4 years in the camps and 2 in exile. He viewed this turn of fate during the investigation as fortunate: priceless material was falling into his hands. Being a man of encyclopedic knowledge and phenomenal memory, he used them to the best effect: while he was still serving the last months of his imprisonment, his book “Place and Time” was published in Paris, where many kind words were said about us, Ukrainians: I heard a passage about myself on Radio Liberty sometime in 1978. In 1983, “Suchasnist” published his book “Ukrainian Silhouettes,” which begins with a long essay on Vasyl Stus and ends with a short one—about me. We, Ukrainians, knew how to suffer much in the concentration camps, but there was no one to write about it. Thanks to the Jew Mikhail Kheyfets: nothing better has been written about Stus to this day than his essay. (This book has also been published here: it was included in the almanac “The Field of Despair and Hope.” Compiled by Roman Korohodskyi. Kyiv, 1994. Also: M. Kheyfets. Selected Works. In three volumes. The essay on V. Stus “There is no one greater in Ukrainian poetry now…” is in vol. 3, pp. 137–225). “Ukrainian Silhouettes” came into my hands at the end of 1990, when the main part of my memoirs had already been written and published in part 3 of the journal “Donbas” in 1990, partly in the 6th issue of “Silski Obriyi,” and first of all—in samvydav.

So Mr. Mikhail would walk along the fence, his hands tucked into his sleeves, his pea coat hanging on him like on a scarecrow, his hat like on a stake, shuffling in his boots, even the gloves that came out from under his sewing machine looked like squashed frogs… “Mr. Mikhail,” I used to say to him, “you must be that legendary Wandering Jew.” There, along the fence, he would conceive whole chunks of books, and then, sitting down somewhere, quickly write them down.

Here, in the 19th camp, there were several Jewish “hijackers”: Mikhail Korenblit, Boris Penson; Mikhail Goldfeld, Lassal Kaminsky, and Anatoly Azernikov had already been released. We had very good relations with them: not for nothing did anti-Ukrainian periodicals at the time write about the “alliance of the trident and the Star of David.” That alliance was strengthened both in the West and in the East—in the Mordovian and Perm concentration camps. But I have a special affection for Kheyfets. He was one of the first to greet me with a kind word in the 17th, where I was brought into solitude, he took a lively interest in Ukrainian affairs, tried to read in our language, and asked me to speak Ukrainian with him. I think not only to learn it, but also to give me the opportunity to speak my mind in my own language. The action in defense of Stus brought us very close. And then this incident happened.

Back in the 17th camp, in Ozerne, Vasyl's cell was searched and a notebook of his poems was taken. In the hospital, he was told that the notebook had been confiscated and destroyed as having no value. A rough draft remained with Kheyfets in the camp. What to do? We had to save what we had. Divide it up and memorize it—Kheyfets suggests to me and Roman Semenyuk. He takes a part for himself as well. But it's not easy. Those poems are heavy, like stones. I hadn't managed to copy more than a few when they took me to Kyiv on July 9. And so, on one of my first days in the 19th camp, in September, Kheyfets brings me a notebook of poems, written in his chicken scratch, and asks me to copy the poems neatly. And then he dictates another two dozen poems to me from memory. This—without knowing our language.

Soon Vasyl returned from the hospital with his notebook. It turned out they had “mistakenly” announced its destruction. Similar “mistakes” were made at the time in the women's camp regarding the drawings, embroideries, and poems of Stefania Shabatura, Nadiia Svitlychna, and Iryna Kalynets. Some were destroyed, but mostly they were just tormented. I remember how Stus, Kheyfets, and Sergei Soldatov went to the KGB colonel Drotenko to argue about this, and all the dissidents in the camp filed protests.

Vasyl managed to send almost all his poems from Mordovia, writing them in a continuous line and replacing certain words with similar-sounding ones: tyurma (prison) – yurma (crowd), Ukrayina (Ukraine) – Batkivshchyna (Fatherland), kolyuchyi drit (barbed wire) – bolyuchyi svit (painful world). So as not to offend the censor’s eyes with “cacophonous,” undesirable words in letters. That same autumn, I copied his entire white-gridded notebook, about 60 pages, and kept those poems until my release, bringing them home safely on March 5, 1977. There were many textual variants in that white notebook. As a pedantic philologist, I diligently reproduced everything, although I did not always agree with Vasyl’s punctuation. At home, I typed them up. My fellow villager, Ivan Rozputenko, saved one copy and brought it to me only after my final release in 1988. Even earlier, I had handwritten them for Kyiv friends and gave the notebooks to Olha Heiko-Matusevych. Sometime in September 1977, the KGB confiscated it during a search of her father's apartment. My own manuscript was lost forever—among others that I entrusted to mother earth. These texts, I believe, are of particular value to textual scholars, as the poems were repeatedly revised and completely rewritten when the author believed they were lost.

When did he write his poems? Although I lived for a time in the same barrack as Stus and worked almost next to him, I rarely saw it happen. Because writing in the camp is not entirely safe: any guard can take an interest in what you are writing, and might even take it away “for inspection.” So Stus only wrote down the poems; they came to him always and everywhere. This was a man whose mind worked without rest. And this work of the brain was noticeable in that individual words of his inner monologue would break through to the outside. This was especially noticeable after his time in the punishment cells, where a man is free to mumble to himself, where self-control weakens. His tense, pained, focused face rarely brightened, except in good company, or when he was asleep. Then you could see a completely different Vasyl, almost childlike. It seemed to me that this man kept himself in iron shackles his whole life, encasing his refined poet’s soul in the armor of a warrior.

Once he sang a song that came to him in the summer of 1971 on St. Volodymyr's Hill in Kyiv, in anticipation of his fate, which became intertwined with the fate of the “Sixtiers” and of all Ukraine. I remembered the melody—impetuous, courageous—and sang it to Vasyl many years later in the Urals, when we were on a walk in neighboring “yards.” “A little off,” Vasyl said, but did not correct me on how it should be. It seems to me that Olha Bohomolets sings it “a little off” now. And the Telnyuk sisters—Halia and Lesia.

The proud cliffs of the Slavuta still green,

the river’s churned surface still gleams blue,

your time has already passed you by, a flying bird,

your last, ahead—the fall.

The sky is still deep, the sun is still high,

but the heart, too small for the chest, will not burst:

the beautiful torments have broken off, gone away,

and something calls you, and something beckons you!

Your unfurled heights have flown by,

ahead—the abyss! And do not close your eyes.

You see the crossroads? Pray.

For you are not yet a warrior, and you are not yet a man.

The proud cliffs of the Slavuta still hunch over,

but the world plunges headlong down.

Cling to the cliffs, like a thorny bramble,

grasp for the sky, like an apple blossom.

Horizon beyond horizon, distance beyond distance,

until the tense day burns out.

The poplars have raked away in high sorrow

your viburnum-red, primordial, longing songs.

For a boundless foreign land has already appeared,

and the green expanse withers in grief.

Farewell, Ukraine, my Ukraine,

a foreign Ukraine, farewell forever!

In the 19th camp, in the village of Lisove, Vasyl served out his “five-year plan” to the last day, until January 11, 1977. They put him to work grinding clock cases—wooden bodies for the clock mechanism—on an emery wheel. This new “profession” did not come easily to him. He was angry that he had to expend effort on it, to concentrate, instead of working mechanically and thinking his own thoughts. Our colleague, also a philologist, but an Armenian one, Razmik Markosyan, and I tried to help Vasyl after finishing our own work, but it was not easy for Vasyl to accept help. However, the conditions here were easier, the work more varied, the camp large, the barbed wire not always pricking your eyes. And most importantly—a much wider circle of people to communicate with. There were about 300 men here in total, about half of us were Ukrainians. Approximately a third were convicted on charges of collaborating with the Germans during the war. Far from all of them were guilty of that: those whose guilt the authorities had no doubt about had long been shot. But here there were many who had become victims of militaristic policy: if there is international tension, then society must be “heated up” from within. So they catch “enemies”: “traitors” from the past and modern potential “traitors to the motherland”—dissidents. To make others afraid: every such trial was written about in regional and district newspapers, talked about on the radio, but for the most part, it was all KGB fantasy. The largest number of such prisoners were Belarusians and Ukrainians, many of whom were nationally conscious.

The second part of the “contingent” consisted of men who had fought with weapons in hand in the 40s and 50s against the Soviet occupiers: Ukrainian insurgents, Lithuanian “Forest Brothers,” Estonians, and Latvians. Among them were several Ukrainian 25-year-term prisoners: Mykhailo Zhurakivsky from Yasenia, Ivan Myron from near Hoverla, Mykola Konchakivsky from the village of Rudnyky in the Mykolaiv district of the Lviv region, and Roman Semenyuk from Sokal.

The last third consisted of “dissidents” of various shades: young Lithuanians Vidmantas Povilionis and Romas Smailys, the young Latvian Maigonis Rāviņš, the Armenians Razmik Markosyan and Azat Arshakyan, the Moldovan Gicu Ghimpu, the Jews Mikhail Kheyfets, Boris Penson, and Mikhail Korenblit, the Uzbek Babur Shakirov, Russians from the Estonian Democratic Movement Sergei Soldatov, and a Ukrainian who had lived in Great Britain for 29 years, Mykola Budulak-Sharyhin. Towards the end of the year, they transferred Vladimir Osipov, the editor of the Russian Christian journal “Veche,” to us from Barashevo.

Among the Ukrainian “dissidents” at that time were the Kharkiv engineer Ihor Kravtsiv, who began to take an interest in Ukrainian culture in his thirties, which aroused the authorities' suspicion. For reprinting a few pages of Ivan Dziuba's work “Internationalism or Russification?” and for a few telephone conversations, he got 5 years of imprisonment. Ihor was one of Vasyl's most interesting interlocutors, although they disagreed on some things. I remember being present during one of their principled conversations: Ihor was trying to convince Vasyl that he needed to take care of himself, not to be in a state of constant confrontation with the administration; after all, he had to realize that he did not belong only to himself: our nation may have struggled for who knows how long to give birth to Vasyl Stus, and he would just go and perish in another hunger strike that he could have avoided. Mr. Ihor himself had to be very careful, as he suffered from constant headaches. Vasyl, however, was uncompromising.

Mykola Budulak had just returned from Vladimir Prison. He was from the Vinnytsia region. At 15, he was taken to Germany for labor. He ended up in the British occupation zone and went to Britain, where he graduated from the University of Cambridge. He lived without citizenship, as it was difficult to obtain there, but that didn't stop him from traveling around Europe on business for his firm. But in 1969, he came to Moscow—and there they suddenly discovered that he was a Soviet citizen who had evaded military service (at 15, during the German occupation!) and was also spying for Scotland Yard. This became necessary because a large group of Soviet officials had just been expelled from London for gathering unauthorized information. The court went to deliberate—and did not return. Three years later, Budulak was informed that he would serve 10 years. “Never mind, the Queen of England won't declare war on the USSR over you.” Mr. Mykola was fluent in English, French, German, Polish, and Russian, so Vasyl had someone to consult with about the nuances of languages while translating Kipling and Rilke.

There were older Ukrainian dissidents here, such as Kuzma Dasiv from Boryslav. In his youth, he had also been a laborer in Germany, about which he told many stories; Mykola Hamula and Mykola Hutsul from Horodenka in the Ivano-Frankivsk region—typical distributors of Ukrainian samvydav. In general, at that time, the Ukrainian ranks in the 19th camp had thinned out: Mykola Slobodian, Petro Vynnychuk, and Yaromyr Mykytko were transferred to the Urals; Kuzma Matviyuk, Lyubomyr Starosolsky, and Hryhoriy Makoviichuk were released.

Vasyl treated the participants of the national liberation war in Western Ukraine with particular respect, sparing no time to ask them questions. And when old Hutsul Mykhailo Zhurakivsky, from Yasenia near Hoverla, would take out his Jew's harp from his bag on Sundays and alternately play and sing melodies that smelled of such ancient antiquity that one's heart would ache: “But wander, little wanderer, but wander, wander…,” Vasyl would become deeply moved and ask the old man to play more. (“He plays the Jew's harp so plaintively, you could call on the Lord for help.”)

His younger countryman, Ivan, with the surname Myron (a type of Ukrainian surname), was also serving 25 years. He was captured at the age of 22. He lived with his preserved youthful respectful attitude towards elders, almost worshiping his recently deceased mother, and avoiding conversations about women. Still young in appearance, he had already gone through such hardships that it made your hair stand on end. Without a shadow of pride, he would talk about the uprisings in the camps in the early 50s:

“We were going to our deaths, women lay down under tanks, they were crushed by the tracks, but we still broke the Stalinist concentration camp regime. That's why we can't let them take away from us, one by one, the rights we won so hard.”

For him, a man of deep faith and broad education, who knew several languages, politeness and intelligence were natural, so do not doubt that this story, which happened to him, is entirely true, though it may seem incredible to some.

He was sitting in the section on his bunk one day, surrounded by dictionaries. The deputy chief of the colony for regime, Lieutenant Colonel Velmakin, comes in (hissing the ‘s’ sound):

“Citizen-convict, why are you not standing up and greeting the chief?”

“Where I come from, the one who enters greets first.”

Velmakin gave Myron 5 days in the punishment cell. The prisoner served them without taking a single crumb of food or a drop of water.

Some time later, the situation repeated itself—10 days. Myron spent them in the same way, surviving only on prayers. He barely made it out of the punishment cell and collapsed. Mykhailo Zhurakivsky picked him up and nursed him back to health. He gave him tea, pressing down his tongue with a spoon, because his tongue filled his whole mouth. After that, Myron seemed to age somehow and stopped playing volleyball with the boys.

We asked him how he dared to go on a “dry” hunger strike. After all, it is known that one can die from it even on the third day from dehydration, a blood clot can form from the thickening of the blood, one can be poisoned by one's own gastric juices. As for a regular hunger strike, irreversible processes—the body's “self-consumption” of less important organs—begin around the fortieth day. Even if you stop the hunger strike, you are already a dead man walking. It is no wonder that Jesus Christ fasted in the desert for 40 days. There is nothing accidental in the Holy Scripture. Later, in 1980, the IRA (Irish Republican Army) boys, led by Bobby Sands, went on a hunger strike. They demanded political prisoner status. But the “Iron Lady” Margaret Thatcher was adamant. Bobby Sands was elected a Member of Parliament during the hunger strike. Ten of them died, the rest stopped the strike. The shortest one lived was 39 days, the longest—69. Surely the conditions in British prisons were somewhat better than in Russian punishment cells.

Here is Mykola Konchakivsky—a hefty fellow from Rudnyky near Mykolaiv in the Lviv region. He “rolls logs” at the sawmill. I remember when I was first brought here on April 12, 1974, he was one of the first to approach me, greet me, ask how many years I had brought with me (it's not customary to ask about the case), and pat me on the shoulder like a father, saying:

“Never mind, Mr. Vasyl, you'll serve your time no worse than others. I've been fighting for thirty-five years now. Ever since I joined the Polish army in '39, I've been at it. My twenty-nine years are almost up.”

When I heard that, my 4 years, which had seemed like a very long term, suddenly shrank and became so pitiful… Later, Mr. Mykola told me he had three graves: one in Poland on an obelisk to the defenders of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and twice his family had received news that he had fallen, and they held memorial services for him. Mr. Mykola served his 29 years, returned home in the autumn of 1977, and died a month later…

I must also mention the Lithuanian partisan Liudas Simutis, who also communicated with the younger generation without fear of persecution.

This, I believe, was our closest circle, which would gather on Sundays and holidays for “tea,” though the tea was only a pretext, a diversion for the guards, who sometimes broke up such gatherings, especially before protest actions and Soviet holidays. It was here that all the news was discussed, here that fascinating conversations took place, which I could now only reconstruct, as I am unable to retell them verbatim.

I arrived from the transport very weakened, but fortunately, the autumn of 1976 was surprisingly rich in mushrooms. Honey mushrooms grew everywhere in the industrial zone, and champignons under logs and boards. I became more skilled at mushroom picking than anyone. Ihor Kravtsiv would clean them, and Roman Semenyuk would cook them, hiding in some nook, of which there were many in this camp. We often got “burned” doing this, but still managed to get some extra nourishment for free. Because the food in the dining hall was something I don't even want to remember. And the bread was good only when the bakery in the camp burned down and for two months they brought us human bread, not the special zek-baked kind. Usually, we would invite Stus, Budulak, and Konchakivsky for these mushrooms.

“Khayma,” Vasyl would say. “They must have sewn a zek’s stomach into me somewhere in that ‘Gaazy.’ It only accepts thin soup, but not human food.”

“Khayma” was Vasyl's little word, which, as he jokingly explained to me, was supposed to be short for “khay katuyut chorty yoho mamu” (let the devils torture his mother).

There, over tea, our assessment of the events and the reasons that brought us, the next generation, which came to be called the “Sixtiers,” to the Soviet concentration camps was formed. Since I was one of the youngest in our circle, it was natural that I always sat at the edge of the table, for which Vasyl nicknamed me “skrayechkusyd” (edge-sitter). That's roughly how I felt in the Sixtiers movement: as if I had jumped up and grabbed a higher rung than I deserved, and was just hanging there, dangling my legs and thinking about how to pull myself up when I didn't have the strength. After all, the leading figures of the Sixtiers were people 10–20 years older than me; there were only a few of my peers in the camps. It seemed to me that among the students of philology at Kyiv University who gathered in the SICH (the Vasyl Chumak Literary Studio, once founded by Vasyl Symonenko, Ivan Drach, Tamara Kolomiyets), many had a good chance of being arrested in 1972–1973, but for some reason, I was the one who “fell into the chosen number.” Maybe because I was lucky to have older friends who, for all five of my student years, gave me Ukrainian samvydav literature to read, and I, conspiring and hiding behind my Komsomol pin (I was even a group Komsomol organizer), gave it to literally dozens of my friends to read. And no one turned me in, which later greatly surprised investigator Mykola Tsimokh:

“Why did no one ever give me anything when I was studying at the law faculty of the university ten years earlier?”

“Because I chose decent people…”

So, without appearing in public, say, at the Shevchenko festivities on May 22, without frequenting the Ivan Honchar Museum, without flaunting an embroidered shirt (because I didn't even have one), without making personal acquaintances with the “leadership,” I was nevertheless aware of almost all the affairs of the resistance movement. I had in my hands almost all the samvydav of that time: Vasyl Symonenko’s “Diary” and poems, Mykhailo Braichevsky’s “Reunification or Annexation?,” Ivan Dziuba’s “Internationalism or Russification?,” Yevhen Sverstiuk’s “A Cathedral in Scaffolding,” “Ivan Kotlyarevsky Laughs,” “The Last Tear,” “On Mother’s Holiday,” Mykhailo Osadchy’s “Cataract,” Valentyn Moroz’s brilliant essays “Report from the Beria Reserve” and “Among the Snows,” Viacheslav Chornovil’s “What and How B. Stenchuk Defends,” “Woe from Wit,” all five issues of the “Ukrainian Herald,” and much more.

The arrests of January 12, 1972, were a profound drama for me: people who had been my guiding stars suddenly found themselves beyond a dark horizon. To remain silent was unbearable, but I was not yet capable of acting at their level, especially since, having graduated from university that year, I had to go to a village to teach. No one anywhere. Well, I had to slowly prepare a new generation, especially since before me were still pure, untouched souls, capable of taking things on faith. But I only taught for half a year: on the 20th anniversary of the Great Despot's death, March 5, 1973, I was arrested in the village of Tashan in the Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi district of the Kyiv region and soon joined the case of Vasyl Lisovyi and Yevhen Proniuk. Not without reason, for in the spring of 1972, I had helped them publish the next, sixth issue of the “Ukrainian Herald,” the idea of which was to divert accusations from those arrested, and I also helped Lisovyi produce several dozen copies of his open letter to the deputies of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR in defense of those arrested. (It was published in issue 8 of the journal “Zona” in 1994).

Lest the reader think I have written a memoir about myself and not about Stus, I will skip my own case here and outline only the most interesting, socially important moments.

At our trial in November–December 1973, prosecutor Makarenko proclaimed, with what he thought was irony:

“These were the great leaders of a small movement.”

But he was right. A small circle of people obsessed with the national idea, who “grew from small, thin mothers” (M. Vinhranovsky) after the Holodomor, the war, the repressions, awakened by the spring wind that blew after the 20th Congress of the CPSU in 1956, warmed by the fatherly hand of Maksym Rylsky—they had not yet unfolded a great national liberation movement. They were still stewing in their own juices, pulling threads from the 1920s through a thirty-year desert into their plundered present. They did not go too far. Although they rallied around the “Ukrainian Herald,” they completely rejected the idea of creating an organization. Many underground groups sprouted in Ukraine, but none managed to expand beyond a dozen or two members before they were arrested. The Sixtiers, it seems to me, held together on personal friendships. Yevhen Sverstiuk once remarked: “When so many glorious, talented, good people gather together, something will come of it.” But they thought their time had not yet come to go out into the public, although hiding from people was even worse. Where there is an underground, there is distrust. The core of this circle in Kyiv was Ivan Svitlychny, Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstiuk, and Viacheslav Chornovil.

In 1970, the “Ukrainian Herald” began to be published, edited, as is now known, by V. Chornovil. In typescript, in a very small circulation. Illustrated with photographs. But our enemies duly appreciated it, because they understood where it was leading. There were rumors that the head of the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR, V. Nikitchenko, himself had a conversation with Ivan Svitlychny, in which he said: “We tolerated you as long as you were not organized. Now that you have a journal, which is a sign of an organization, we must take measures against you.” It was said that Nikitchenko had once studied with Svitlychny's wife, Leonida Pavlivna, and treated Ivan with respect. Rumors of possible arrests, of a list of 600 people, began to spread. In the summer of 1970, Nikitchenko, as too loyal, was replaced by V. Fedorchuk, brought from Moscow. It was said that P. Yu. Shelest was against him, but Shelest’s own days were already numbered: it was no trouble to gather compromising material against him, and he agreed to the arrests. They were looking for a pretext. Although the 5th issue of the “Ukrainian Herald” announced that its publication was being discontinued, this did not save the Sixtiers. The pretext for the arrests was, as always, a political provocation.

At the end of 1971, a Belgian citizen, a member of the Ukrainian Youth Association, Yaroslav Dobosh, came to Kyiv via Prague and Lviv. As I later learned from my classmates, Lemkos from Prešov, Mariya Hostova and Anna Kotsur, he had met with Anna in Prague, and she had given him the phone numbers of several people in Kyiv and Lviv. Later, in the materials attached to our case from Svitlychny's case, I read that Dobosh had had telephone conversations and meetings with Svitlychny and someone else right in the hotel and on the street. Nothing special was said, so no one paid any particular attention to Dobosh. In Kyiv, Anna gave Dobosh a microfilm of the “Dictionary of Ukrainian Rhymes,” which Sviatoslav Karavansky had compiled during his long years of captivity. This dictionary had been passed from hand to hand; several university departments had recommended it for publication. But the author was once again in captivity—so the dictionary automatically became “seditious.” Later in the press, it was referred to as “one anti-Soviet document” (see the newspaper “Literaturna Ukrayina” of June 6, 1972). Dobosh was returning home for the New Year when he was arrested and accused of espionage. He got scared and told them who he had seen and what he had talked about in Kyiv and Lviv. A photocopy of his statement was in our case with Lisovyi and Proniuk. If it had been published in full (the Soviet press only gave snippets with appropriate interpretation), everyone would have been convinced of the clumsy case the KGB had concocted under Fedorchuk's command. But no matter: the pretext was there. A rumor swept through Kyiv: on January 12, Ivan Svitlychny, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Viacheslav Chornovil, Vasyl Stus, Zinovia Franko, Mykola Kholodnyi, Oles Serhiyenko, Leonid Plyushch, Vasyl Zakharchenko, Leonid Seleznenko, and Mykola Plakhotniuk were arrested... In Lviv, Iryna Kalynets, Ihor Kalynets, Stefania Shabatura, Ivan Hel... Dozens of names were mentioned. The newspapers “Radianska Ukrayina” and “Pravda Ukrainy” on January 15 published a few lines about Dobosh’s arrest, and on February 11, a few more lines ending with something like: “For conducting anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR and in connection with the case of Ya. Dobosh, I. Svitlychny, E. Sverstiuk, V. Chernovol, and others have been arrested.” Exactly so: “Chernovol.” And behind “and others” stood dozens of people, hundreds of searches, thousands of summonses for interrogation, dismissals from work, expulsions from universities, blocking the children of the arrested or anyone even remotely connected from higher education… Borys Kovhar was arrested. Anna Kotsur was detained for a while, then she stayed for some time in the Czechoslovak consulate, as if it were some kind of refuge after the occupation of the entire country… Ivan Dziuba was detained and released, but on April 18, he was finally arrested. On May 18, Nadiia Svitlychna was arrested… No one was charged with “espionage,” only with “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda,” but the aforementioned newspapers have yet to see fit to publicly apologize for this.

Kyiv is paralyzed. I, then a fifth-year student of Ukrainian philology at Kyiv University, experienced those events as a personal tragedy. Vasyl Lisovyi, a philosopher with whom I had become close when I was a freshman and he was a graduate student teaching us logic, and who for all these years had given me Ukrainian samvydav to read, was walking around looking black as night. One day he asked me for help: there was an idea to publish another issue of the “Ukrainian Herald” to divert the accusations from those arrested. I bought paper, transported something somewhere. But when I got the entire “print run” (some ten typescript copies on thin paper) into my hands and went to my sister’s apartment to proofread and collate it—I felt that what I held in my hands was the most important thing in Ukraine at that moment. There was a report on the arrests, brief information about the arrested. Then followed a letter from Borys Kovhar to KGB investigator Colonel Danylenko about how he, Kovhar, was “sent” into the environment of the Sixtiers to inform. He did this for a while, but then, convinced that he was dealing with the best people in Ukraine, he tried to refuse the shameful craft. But the KGB punishes its “renegades” with particular mercilessness: Borys Kovhar spent ten years in a special-regime psychiatric hospital.