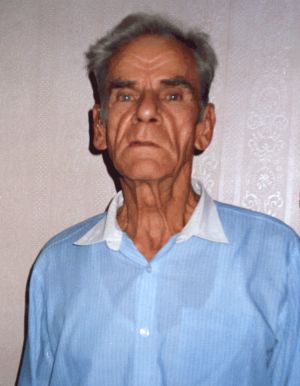

VASYL KONDRYUKOV. MEMOIRS.

The suggestion to record something from my past on a dictaphone was unexpected. Therefore, what was recorded on it has some errors and inaccuracies. It’s true that Mr. Drobakha called me once and said he wanted to visit me with Vasyl Ovsiienko. But I thought we would just sit, talk, and go our separate ways, as often happens. So I suggested that I write down my memories on paper without a dictaphone and pass them on in a few days. Mr. Ovsiienko objected to this: “We’ll never get anything done this way.” But for me now, without a diary (I never kept one), to sift through my forty-year-old, already settled thoughts was too much. What was supposed to settle has settled and fossilized. What floated to the surface has long been carried away irreversibly by the stream of time. And that is not the main thing now. Currently, Ukrainian statehood is in danger. The threat of losing independence is hanging over us. A coup has occurred. An anti-Ukrainian coalition has come to power. We must think about how to save Ukraine. Who needs the memories of a mere mortal today? Who will read them? When even the memoirs of prominent or famous people are read by no one. And if someone does read them, what's the point? What will it give? Whom will it influence? Still, I had to confess, give testimony, that is, answer Mr. Ovsiienko’s questions.

V. Ovsiienko: Last name, first name, and patronymic? Where were you born? Who are your parents?

I, Vasyl Oleksandrovych Kondryukov, was born on March 24, 1937, in the village of Vyshne-Hrekove (now Vyshneve), Rovenky Raion (now Antratsyt Raion), Luhansk Oblast. My wife, Zinaida Tarasivna Kondryukova, was born on June 13, 1942, in the village of Orikhove, Antratsyt Raion, Luhansk Oblast. After graduating from the agricultural technical college in the settlement of Uspenka, she worked as an economist at enterprises in the city of Kyiv. She is now retired. My older daughter, Olha Chornous, was born on September 26, 1964, in Kyiv. She has a secondary specialized education. She lives with her family in Kyiv. My younger daughter, Tetiana Kondryukova, was born on March 13, 1974, in Kyiv. She has a higher education. She lives with her husband together with us.

My father, Oleksandr Kyrsanovych Kondryukov, worked in a kolkhoz, then at a mine. He did not return from the war. My mother, Mariia Ivanivna Kondryukova, worked in the kolkhoz her whole life. At the beginning of the war, she was left with five children. My older brother, Dmytro Oleksandrovych Kondryukov, was born in 1929. His whole life, except for his army service, he worked in a mine. He is now retired. He lives in the city of Rovenky, in the Luhansk region. He has a daughter, Halyna, who lives with her family in the city of Sevastopol. She published her collection of poems titled “Destroyed Horizon.” Veber Publishing House, Sevastopol, 2006. (Dmytro died on June 21, 2007). My second brother, Mykola Oleksandrovych Kondryukov, was born in 1931. He also worked in a mine his whole life (except for the army). He had a 7th-grade education. He lives in the village of Vyshneve, Antratsyt Raion, Luhansk Oblast, on our parents’ homestead. He has a son who lives in Luhansk with his family, and a daughter who lives in Antratsyt with her husband and children. My sister, Yevdokiia Oleksandrovna Kondryukova, was born in 1934. She finished 7th grade. She lives in Antratsyt with her daughter and grandchildren. There was also a sister, Alla, born in 1941. But she died at the age of 40.

I went to school in 1944. The war had not yet ended, but the Germans were no longer in Donbas. I remember May 9, 1945. We are sitting in a lesson in a large room. It was a one-story landlord’s house with five rooms. One, a small one, was occupied by the director, the second was the office, and the rest were classrooms. Suddenly, the party organizer, Petro Vasyliovych, is walking down the road and shouting something at our windows. Halyna Tykhonivna opened the window and he told her that the war was over. Classes stopped immediately. We were put in a column, given flags, and we marched through the whole village from one end to the other. It was Victory Day. But now I think that for the Ukrainian people it was the Day the War Ended. That is how it should be commemorated. It would be blasphemous to celebrate on this day when millions of people died. After all, there was no victory for the Ukrainian people. Having freed itself from one yoke, Ukraine fell into another. In the contest of two fascisms, the stronger one won.

My childhood fell during the war and post-war years. We crawled through all the gullies and ravines. In the spring, we dug for *buzuluks* [a local plant root] and lit bonfires. We found cartridges, grenades, and shells. It was interesting to watch the long, yellowish powder from the shells burn like vermicelli. We made homemade guns. One time, on “Kharytyna” (the name of a vacant lot between homesteads), we lit a big fire, threw cartridges into it, and lay down nearby. It was interesting to watch the cartridges pop and the bullets whistle over our heads. This time we got away with it, but it didn't always end well. Some were wounded, had their fingers torn off. And they couldn’t even collect Mykola Kulykivskyi’s body after a shell exploded. A few days later, Borys Yehorov and I found a boot with a foot in it and took it to the cemetery. Once I came home in the evening. Mother grabbed a switch: “Were you dismantling shells with Borys again?” “No, I wasn’t dismantling them. Borys was. I just sat and watched what he was doing.” Mother turned away, dropped the switch, and went into the house.

I remember 1947. I despair when the war is named as the cause of the famine. But immediately after the war, from 1944–1946, the people did not starve. In 1946, the kolkhoz workers were given nothing for a workday. They were promised they would be paid from the future harvest of 1947. In the gardening brigade where my mother worked, they recorded 0.6–0.7 of a workday for a full day of labor. They were paid for the workdays at the end of the year with goods, after the state procurement plan had been fulfilled. People cut down their orchards; fruit trees could not cover the high taxes imposed on each tree. Whoever had a cow had to deliver the milk to procurement; eggs from each laying hen were also given to the state. The skin from a piglet had to be handed over. Those who tried to secretly raise and slaughter a piglet received large fines. People were prosecuted for picking up grain stalks from an already harvested kolkhoz field. I got a taste of it myself. A tractor in “Kuteriv” (about five kilometers from our house) was plowing a harvested field for winter crops, and where it wasn't yet plowed, I collected about a third of a bucket of grain stalks. Out of nowhere, a mounted patrolman appeared, quickly caught up with me, and I had to pour out the stalks. The case didn’t go to court, but I walked around with a red stripe on my back from his whip for a long time.

In the winter of 1947, there was a period in our family when we all had to live on nothing but pickled cucumbers for three days. We had been living on the verge of starvation since December 1946. My older brother Dmytro dropped out of school (he was in the 10th grade) and went to work at the “Vengerovka” mine, which was eight kilometers from the village. An underground worker was given ration cards for 1.2 kg of bread. For each dependent listed under him, 250 grams of bread were given. Every day, Dmytro brought home 2.45 kg of bread—this saved our family of six from starvation. The boy, not yet 18 years old, exhausted and hungry, would search for a lump of anthracite on the slag heap after work and carry it home on his shoulders for 8 km. That's how we survived the winter. When spring came, it was paradise, especially for the children. We would eat the blossoms of the willow, which was one of the first to bloom in spring. We would dig up the garden, looking for rotten potatoes from which starch would settle at the bottom of the water. Then we ate goosefoot, nettles, irises, and all other non-poisonous herbs.

The name of the village Vyshne-Hrekove comes from the surname of Yesaul Grekov. Until 1782, the lands where the village is located belonged to the state and were called free lands. Serfs who fled from their landlords hid in the gullies. In 1782, a demarcation took place between the Don Host Oblast and the neighboring guberniyas. All the previously free lands were transferred to the Don Host Oblast. The Mius Okrug (named after the Mius River) was created. According to the laws in force at that time, all generals and officers of the Cossack troops were allotted plots on the free lands upon retirement. The people who lived on these plots became the property of the grandees and were automatically enserfed. The name of the village was given according to the owner's surname. In the Rostov Oblast Archive, an enthusiast of antiquity, a resident of our village named Oleksiy Yakovych Kondryukov, found some documents in 1966 about the founding of the village. A sample of a document:

Комиссия Высочайше

учреждённая для

размежевания земель

Войска Донского

…………………………………….

Канцелярия

…………………………………….

Новочеркаск 26 июня

1843 г., № 663

В Войсковое правление Войска Донского. На основании решения Господина Военного Министра от 13 марта 1841 года №726, комиссия сделала дозволение Есаулу Тимофею Грекову (отзывом на имя его от 26 июня 1843 г. №662), 43 душ ревизских мужского пола крестьян его, состоящих Миусского округа в посёлке Вишневецком Грековом, переселить довольствие того же посёлка на левую сторону речки Вишневецкой по течению ея выше существующего ныне селения и основать новый посёлок при устье оврага Куханного близ устроенного им, Грековым, тока, против урочища, именуемого Большим Пристеном.

Подписали:

> Членъ. Статский Советник Воронченков

Членъ. Полковник Бахтистов

Скрепил Правитель Канцелярии Подполковник Пудавовъ

Верно секретарь (підпис нерозбірливо).

The Kondryukov family originates from the Cossacks. In the “Act of Purchase and Sale of Serfs,” there is a registry entry: a certain Khorunzhy Ushadov from the Donetsk Okrug sold five male souls of the Kondryukovs, demoted from Cossacks to peasants “for disobedience and robbery.” The buyer turned out to be Grekov. The transaction was made in 1842. (Rostov Oblast Archive). As for the surname Kondryukov, there are two versions. According to the first, as Oleksiy Yakovych claims, the word “kondryuk” means refugee. It is clear to everyone where the “ov” came from. I heard the second version from the Crimean poet Halyna Dmytrivna Kondryukova. She consulted an expert on Eastern languages at Simferopol University, who said that “Kondryukov” in Persian means “Bright Day.”

As is known, the inhabitants living on the territory of future Ukraine, as early as the sixth millennium BC, invented the wheel, domesticated the horse, and engaged in agriculture. The lineage spread. In search of new lands, separate clans reached the lands where the state of Iran is now located after several centuries. And it is quite possible that local residents elected one of the arriving elders as a leader and called him “Bright Day” for his white skin, light hair, and, not improbably, for his bright mind. So the descendants of “Bright Day” returned with the surname Kondryukov. And the very name “Iran” is consonant with Orianta, Oranta—the name of the country that existed at that time on the banks of the Borysthenes (later Slavutych, Dnipro) and Desna.

I finished seven years of school in my village. The instruction was in Ukrainian. There was no paper; we wrote between the lines on pages torn from various books. We made ink from elderberries. For the eighth through tenth grades, I walked seven kilometers to a Russian-language school in the settlement of Mykhailivka. After finishing tenth grade, I studied at a school for electrification. A year later, I graduated and got a job at a mine. Then came the army, 1957-1960. I joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the army, not in 1961 as Nazarenko writes in *Vyshhorod Legends*. At that time, I wouldn't say it bothered me, but the thought sometimes crossed my mind: “To do something useful for my people, I need to get ahead in life. That is, to have some power. And it was impossible to achieve anything at that time without the Party.” Later I realized this was a mistake. Only those similar to the ones already in power were allowed onto the rungs of power. The slightest manifestation of free-thinking ruined a career. No matter what rank you held, you couldn’t do good for the people. (Even if you didn’t drink vodka with them, you’d look like a black sheep and quickly fall). After demobilization in 1960 and until June 1961, I was back at the mine.

In 1961, I left the mine and went off into the world to seek a different fate. I ended up in Vyshhorod at the construction of the Kyiv HPP. I worked as an electrician in the Hydrospetsbud department. At first, I lived on landing stages (large barges adapted for people to live on). Then I lived in a metal wagon, which was hot in the summer and cold in the winter.

Gradually, people appeared among my acquaintances with whom I could be more or less open. I spoke both Russian and Ukrainian, depending on which language someone addressed me in. We would gather in groups of three or four. At our meetings, we were allowed to say whatever we wanted. We discussed issues such as the role of the Ukrainian proletariat in the international movement. That the friendship between peoples would be stronger if they lived separately. Because in one house with several families, even children quarrel with their parents. We rejected clumsy examples regarding the USSR about the superior strength of a bound broom over individual twigs. After all, in the USSR at that time, it was not individual “twigs” that were bound, but 16 “brooms” (republics). And in such a state, they could not be capable of anything until someone untied them or their bonds rotted away. We considered the amputation of Ukraine from the empire to be fatal for the union. We knew that a mixed dish is better digested in the empire’s stomach. There were conversations on the national question—the development of language, literature, culture, and so on.

Everything went on its own. It was not a party. We jokingly called ourselves the Party of Real Communism (PRK), not the Party of Honest Communists, as Oles Nazarenko calls it in *Vyshhorod Legends*. We had no program documents, no statute. But still, we at least thought a little about something. A critical way of thinking was developing. We saw that something was wrong with life, but we didn’t know how to change it. These were steps towards self-awareness. And consciousness quickly evolved towards Ukrainian statehood.

When I met Volodymyr Komashkov, all these issues were proposed for discussion. Later, he even wrote a poem as a response to the idea that the main role in international relations is played not by the people, but by their leaders.

«Уйдите! Станьте в стороне!

Сойдите на обочину!

Я сам дорогу проложу

К американскому рабочему!»

At the HPP, Komashkov was known as a Komsomol poet. Ultimately, that’s what he was at the time. He changed his surname from Komashko to Komashkov (according to his own accounts). Later, probably under the influence of samizdat literature, he changed internally, but outwardly remained the same. I think it was a necessary mask at that time. Already after my dismissal, somewhere in the mid-seventies, it was very sad to see him with the red armband of a volunteer druzhyna. When we started talking about the past, he jokingly recalled the words of the local KGB officer, said to him: “Your ten years are in my pocket.” I don’t know what he wanted to emphasize with this. Probably the significance of his role in our cause. Although, indeed, the role of Volodymyr as a supplier of samizdat literature, and of Nazarenko as a reproducer and distributor, was undeniable. Almost all the samizdat came through Komashkov to Nazarenko. I never saw Volodymyr engage in the production or typing of texts, photoreproductions, or films. He got them ready-made. When we met in the laboratory where he worked, some materials lay on his table along with newspapers and magazines. With his tacit consent, we took these materials for reproduction ourselves. It turned out that Komashkov was not involved in distribution. This allowed us to claim this during interrogations. I met Oles Nazarenko a little later than Komashkov. He was a restless person, constantly on the move, and he quickly made friends with people. I always spoke Ukrainian with Mr. Oles. We quickly grew to trust each other. At that time, samizdat had already gained great momentum. A certain part of its avalanche consumed us. The scale of the materials that passed through our hands can be judged from the indictment (attached). It includes *Regarding the Trial of Pohruzhalśkyj*, *Woe from Wit* by V. Chornovil, *Internationalism or Russification?* by I. Dziuba, Djilas, Dontsov, and many others. And not all materials were seized. Yuriy Klen’s work remained with Rima Motruk. I managed to give it to her just before my arrest. I gave Raskolnikov's letter to Stalin to Fedir Filatov. Although they tried, as KGB Major Koval of the Kyiv Oblast said, to pull everything out “by the roots.”

My worldview was broadening. New questions arose. I came to the conclusion that a person first establishes himself within himself, in his own individuality, then in the family, then in the nation, and only then in internationalism. Internationalism was viewed not as a mixing of nations, but as a friendship between free countries. If you reject individuality, family, nation, and impose on peoples a baseless, unsubstantiated internationalism, it can only be held by bayonets. I was aware that without our own independent state, no one would care for our people. We already knew what we didn't want. We knew what we wanted. But how to achieve it—we did not know. Yet a method of struggle was emerging on its own. Spontaneously. In my opinion, Mr. Ivan Hubka is wrong when he writes in his book *In the Kingdom of Arbitrariness. Memoirs. Part 1*, p. 359. “But many of the ‘fighters’ of that time (I put this word in quotes because the struggle was not waged with armed methods) failed to ‘ignite’ the masses with the idea of statehood, to raise them to fight. One of the ‘failed leaders’ of that time was Ivan Dziuba; he lacked nationalist training, was not hardened in the ranks of the OUN-UPA, and ultimately could not withstand the frenzied pressure from the Bolsheviks. It should be noted that at that time, accidental people appeared in the political struggle, people who did not put the issue of statehood at the forefront, but only hid behind demands for partial Ukrainization, in essence, of Ukrainian society. They were satisfied with: the legalization of Ukrainian historical science, the lifting of restrictions on literary activity, a reduction in censorship, and freedom of speech. The documents of those times—statements, articles, complaints of such organizations and societies—testify to these demands. Of course, we do not diminish the contribution of the Sixtiers (as they call themselves) in the process of liberation struggles, but we cannot exaggerate the value of their work in this field either, especially today, when some political leaders place them above the heroes of the OUN-UPA.”

The contribution of the heroes of the OUN-UPA to the liberation struggle is unparalleled. But an illegal armed struggle in the sixties was impossible. People with weapons at that time meant unnecessary victims. Any underground activity was out of the question. Even Levko Lukianenko’s human rights group, which acted without weapons, was sentenced to death. The necessity to legalize the struggle arose. When “on all tongues all is silent” (T. Shevchenko), one had to start with the smallest things. To look for weak spots and try to tear there, where it was possible. Criticism of the existing system forced people to think. Letters to the authorities were distributed among the people and reached abroad. Human thought was stirred. This was a method of struggle. The Sixtiers knew that to reach the cherished goal, at that moment, they had to use the method of legal criticism of the existing system, thereby shaking its foundations. The result of their aspirations confirms this. The Soviet Union fell without weapons. And this was, I believe, the only correct method at that time. There are no misunderstandings between the OUN-UPA and the Sixtiers. On the contrary, there is a sense of the continuity of the Ukrainian people's liberation struggles. Ivan Dziuba, in his work *Internationalism or Russification?*, showed the contradiction of the communist ideology's claims. The monolith of its inviolability was called into question. I did not believe (and, I think, anyone who read this work did not believe) that in *Internationalism or Russification?* he was defending the purity of Leninist policy. I did not consider his repentance sincere. The book spread throughout the world and played an extraordinary role in shaping people's consciousness.

Hubka understands that history is not studied from interrogation protocols signed by the accused themselves, as he writes (ibid., p. 250): “When we are well-fed, as they say, dressed up in a tie, in a warm house, and nothing threatens us, and maybe someone is even looking after us, then it is easy to talk about universal human rights, morality, to condemn someone for ‘breaking,’ asking for forgiveness, and so on. But what would this moralizer do if he found himself in such a situation?! Torn from a warm house, separated from relatives and friends, he soon finds himself in solitary confinement, and the entire criminal machine is working against him. They intimidate him—‘you can get it,’ they don't even promise freedom, but give a choice—ten, fifteen, or more years, and you just have to think. And at home, a wife and children are left, who will probably be taken to Siberia. Let's think before condemning someone, what kind of ‘song’ we would sing. Just as one cannot speak of the truthfulness of protocolled interrogations (they are half-truths, much is hidden, and some things are said unnecessarily under pressure), so one cannot judge the truthfulness of the convictions of the Sixtiers from the literature they wrote based on the existing ideology. After all, this was a cover for spreading truthful information among the population. History, as Mr. Ovsiienko said, is not what happened, but what is written down. And now there is an opportunity to record the truth from people who are still alive, who have overcome fear, because now there is more or less freedom of speech.”

The circle of acquaintances gradually expanded: Hryhoriy Voloshchuk, Rima Motruk, Oleksandr Drobakha, Ivan Honchar, Valentyn Karpenko, Bohdan Dyriv, and others. Nazarenko and I visited Volodymyr Zabashtanskyi, who lived in a one-room apartment in Podil in the early 60s. We invited him to visit the construction site. One day he visited the Kyiv HPP and gave the Kondryukovs an autographed copy of his poetry collection *The Masons’ Order*, which was published in 1967. He read his unpublished poems. We were not allowed to copy them, but some were remembered:

«Скільки відцвіло не наших весен?!

І невже чергова теж чиясь?

Десь несе мене в човні без весел

По ріці життєвій течія.

І немає ні мети, ні долі.

Тільки ятрить душу мука з мук,

Що лежить моя Вкраїна долі,

Як бандура, вибита із рук!»

And his “…straight road from a crooked wheel” impressed me so much that I decided to write something myself. But “he who is born to crawl cannot fly” (M. Gorky). But, it turns out, one can write without God’s gift. Only, to achieve something, you have to dedicate your whole self, to the very end, to the realization of one thing you have conceived. Constantly perfecting it, not scattering yourself across a multitude of other aspirations. As a trial of the pen, I will give an excerpt from a poem I wrote in the mid-sixties.

«…Але під дахом у штучному світлі

Весела мати дітей навчала:

Немов би сяйва усього світу

Лиш тільки звідси беруть начала.

Сокира батька лежала в сінях

І хтось тягнувся до неї нишком,

Якщо не можна рубати стіни,

То хоч би дірку у темній криші.

Much later, around '89 or '90, Zabashtanskyi led a literary circle at the club of the “Machine Tools and Automata” factory, where I ended up at his invitation. I was surprised when, after listening to a critical novella by a young author, he said that the word “Soviet” should be removed from the text and the work would be perceived better. This is how he taught the youth the high art of perfection. At that time, it seemed to me that the fire that blazed in the hearts of young authors should not be nurtured in caves, but brought out into the wind, so that the flame would rage, and its sparks would fly across the whole Country, igniting others. But he, by inertia, kept the fire in a cave, adding the necessary portion of firewood so it wouldn’t go out. Like Prometheus, hiding it from Zeus when he flooded the whole Earth with rain.

I communicated less with Mr. Oleksandr Drobakha than with Nazarenko or Komashkov. As far as I know, he was not involved in reproduction or distribution, but he was familiar with samizdat. Oleksandr was then preoccupied with his poems. He was preparing his first collection, *Fern Flower*, for publication, which came out after our arrest. (The trial took place at the end of January 1969, and *Fern Flower* was published in August 1969). During his vacation, he went to a library in Moscow to, as he said, familiarize himself with Pasternak, Khlebnikov, and Zoshchenko in the original. Returning from there, he repeated the words of the ancient Greeks, recalled (according to him) by V. Chornovil in the Vyshhorod Museum of the Kyiv HPP: *“Carthago delenda est,”* which means “Carthage must be destroyed.”

Nazarenko conceived the museum, and something had already been collected. It was under his bed on the landing stage. But Drobakha “knocked out” a room in the basement of a dormitory and finished the museum. Mr. Oleksandr organized a literary circle under the symbolic name “Crimson Sails.” But there wasn't enough Dnipro wind and air from our lungs to move this schooner, located in the Lenin room where it was situated, from the gravel of the concrete plant. A different monsoon blew. For the very name “Crimson Sails,” the circle was accused of nationalism and disbanded.

I had fewer encounters with Valentyn Karpenko, Bohdan Dyriv, Ivan Honchar, Petro Yordan, and others. When we met, we knew who was reading what and what they were doing. We discussed some information. There was no need to pass on photoreproductions or typed texts. Nazarenko took care of that.

Hryhoriy Voloshchuk, mentioned in the works of H. Kasyanov (*The Dissenters*) and V. Ovsiienko (*Light of People*), and Rima Motruk, his wife, lived in my apartment in 1967–1968 almost until my arrest. We didn’t charge them rent. We (my wife, child, and I) were in one room, and they were in the other, where there was no bed, only a desk with two chairs. In general, he was an extraordinary, unconventional, emotional, restless person. I remember him singing a song with lyrics by Bohdan Lepkyi:

«Чуєш кру, кру, кру, в чужині помру, заки море перелечу – крилонька зітру».

He often drank. But I will not undertake to analyze his actions. He was not able to realize his great potential to the fullest, but he cannot be called a “lost force.” His rebellious activity was that drop that, along with others, fell on the “metal” of the ruling ideology and, like rust, corroded its insides.

There were intentions to create a party. We saw the futility of its creation. All parties were eventually exposed. And ours would also be exposed, no matter how we concealed it. We limited ourselves to cultural activities and criticism of the existing system, hiding behind Marxism-Leninism. Even after the appearance of Viacheslav Chornovil at the Kyiv HPP, who was the first to openly criticize the authorities, using the slightest opportunity at any gatherings. Nazarenko ends his address “To All Citizens of Kyiv” with the words: “Long live the Leninist national policy!”

The amount of samizdat literature that passed through our hands was constantly increasing. Nazarenko and I no longer had time not only to read it, but even to film it. Oles was engaged in filming and producing photoreproductions with me in my home. First in a wagon at the Kyiv HPP, and later in my apartment. I often had to sit up at night making photoreproductions. By the way, Nazarenko and I bought a photo enlarger with our joint funds. But we couldn't cope with the influx of information. The need arose to find a typist. When I made an agreement with Larysa Filatova (the wife of Mykola Savchenko), I gave her a typewriter brought by Oles. At first, Larysa refused money for typing. But when I told her that she might need it for her defense in case of a bust—you could say, “I worked for the money”—she agreed. We paid 20 kopecks for each typed page. Oles was not acquainted with Larysa and therefore, in his *Vyshhorod Legends*, he mistakenly calls her Larysa Panfilova.

We didn't even think about being arrested. On the one hand, I scorned caution; on the other, there was the instinct of self-preservation. My actions resembled some kind of primitive, natural conspiracy that exists in people.

They arrested me on September 17, 1968. Nazarenko claims that a V. M. Pcholkin was sent in, who begged him for a copy of *A Great History of Ukraine from Ancient Times to 1923*, written in an anti-Soviet nationalist spirit. I knew nothing about V. M. Pcholkin. I won't talk about the investigation methods; they are well-known. They are written about by Masiutko, Hubka, Ovsiienko, and many other authors who have been there. I will only say that I was not beaten. No physical torture was applied. Intimidation, exhaustion, nighttime summons, deception, provocations, stool pigeons, and other legal subtleties were in their arsenal. I resisted the investigation as best I could. I confirmed only what was already known to them. To avoid falling for provocations, I demanded evidence. I avoided accusations of creating any organization and downplayed my activities. I said that reading forbidden literature was just a natural human desire to learn something new. In our defense, we had nothing to lean on. The Helsinki Accords did not yet exist, as the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe took place only in 1975. Therefore, we could not refer to legal documents to fight legally and completely lawfully against human rights violations, relying on domestic and international law. At that time, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UN in 1948, existed, but we knew nothing about it. We had to refer to the Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR. To complain about the consequences of the cult of personality and the not-yet-forgotten consequences of the Beria era, which had supposedly been condemned from above but required eradication at the grassroots level. The investigators were not afraid of these statements, but they also lacked a confident, resolute pressure of being in the right. I tried to involve as few people as possible in this process. I did not talk about materials that did not appear in the investigation, which is why I had few witnesses. Thus, Fedir Filatov was left with *Raskolnikov's Letter to I. V. Stalin*, and Rima Motruk had a photoreproduction of Yuriy Klen’s *The Ash of Empires*. It is sad to say, but I was at a disadvantage not only because I had no legal experience, but also because I did not have a perfect command of the Ukrainian language. While I could distinguish “shchykoldu” (latch) from “shchykolotku” (ankle), I did not understand the meaning of the words “nebizh” (nephew) and “nebizhchyk” (deceased). And the words “rozmnozhennia” (reproduction) and “rozpovsiudzhennia” (distribution) had the same meaning for me. It would have been much harder for the investigators to accuse me of distribution if I had known it was not reproduction.

During the investigation, Oles Nazarenko, it seemed to me (my emphasis), was afraid that the authorities would underestimate our activities. He tried to exaggerate and give more weight to our case, although he did not invent anything extra, but spoke the truth. Perhaps he was right. It was necessary to blow up the case so that more people would learn about it.

Ukrainians have always faced the eternal question: whether to fight with arms and perish, or, knowing in advance the doom of such a struggle, to “lie low,” preserving the nation's gene pool for the future. Was it not this problem that divided the Banderites and Melnykites? There are many similar examples in history. But if there were no struggle, there would be no history of a people's struggle for its liberation from occupiers. It would seem that the people had reconciled themselves to their oppressed existence.

If my activity is considered from the perspective of the authorities that existed then, all the underground literature that came to me was anti-Soviet, and therefore criminal to them. That is why at the trial, I pleaded partially guilty to the existing authorities. But according to the universal concept of a free person, I saw no guilt in myself.

Then came the transport. In January 1969, we were put in separate “Stolypin compartments.” No one knew where we were being taken. On one side of Nazarenko's “compartment” was me, on the other—Valentyn Moroz, and behind him—Valentyn Karpenko. We could exchange a few words, but we couldn't see each other. Moroz also joined the conversation at some point. Nazarenko passed him the text of his undelivered speech at the trial through a guard. I said indignantly that he shouldn't do that because we didn't know who was there. We were not acquainted with Moroz and had never heard his voice. We were brought to Kharkiv. We had to cross several railway tracks to get to the “voronok” [paddy wagon]. We were taken out of the train car. There, we saw each other for the first time after the trial. They put us in rows of three along with the “bytovyks” [common criminals]. We were forced to link arms. The command rang out: “A step to the left, a step to the right—I'll consider it an escape. I'll shoot without warning. March.”

We were placed in death row cells on “Kholodna Hora,” each one separately. By the wall, there was a concrete platform on which we had to sleep, putting our hands under our chests to avoid chilling our lungs. A few days later, we were sent off again to an unknown destination. We ended up at the Ruzaevka station in the Mordovian ASSR. Here, the three of us, co-conspirators, were placed in a large cell with the “bytovyks.” There we could lie on wooden bunks. We asked the guards for a razor, but they only gave us one half of a blade. To this day, I am amazed at how Karpenko managed to shave himself and us with that half a blade. The next day we were sent to our destination. Nazarenko was dropped off at the Yavas station, and Karpenko and I ended up on the territory of the prison hospital, which was at the end of this railway branch. Then the hospital was separated by fences, and we found ourselves in concentration camp No. 3. There was a full international here: Ukrainians, Russians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Georgians, Armenians, Jews, and others. There was relative freedom here: the barracks were not locked, we walked around and communicated freely. The railway track by which we were brought here separated the work zone from the residential zone.

Gradually, I got to know many interesting people.

Stetsenko, during the war—the burgomaster of Krasnodon, who is mentioned in Fadeyev's *The Young Guard*. His coachman was Oleg Koshevoy's stepfather. He said that he drove a team of three horses to the scene where young men had robbed a cigarette kiosk (referring to the Young Guards). The Germans, as is known, did not spare thieves; some were shot and thrown into a mine shaft. When Stetsenko's time for release was approaching, he said he was afraid to go to Krasnodon, so he would go with the Baptist Safronov to Russia and join a sect there so that no one would bother him.

Ivan Pokrovsky had been in many camps. He was highly respected among political prisoners everywhere. He said that the conditions here were worse than in camps No. 11 or No. 19. Once in a conversation with him, I mentioned that I would very much like to see my case file. What was my surprise when, after some time, he brought me my indictment, printed on tracing paper. I don't know how he managed it, but it was not customary to ask.

Levko Lukianenko was an undisputed authority. When he familiarized himself with my indictment, he said with astonishment: “And this was happening in Kyiv, right under their noses! It means our cause is not so hopeless after all.”

Sinyavsky, well-known at the time, said after a conversation: “I considered you to be extremists.”

Valentyn Karpenko got a guitar somewhere and composed wonderfully, knew many songs, which he would recite in a singsong manner in his free time. He memorized almost all of Vysotsky by heart. Not only Ukrainians gathered around him.

Karpenko was friends with Mykola Tarnavsky, a teacher from the Kirovohrad region. Ivan Hubka and I would sing Taras Shevchenko's “My Thoughts, My Thoughts.” I also communicated with Mykola Bereslavsky from Berdiansk, who on February 10, 1969, attempted self-immolation in the lobby of Kyiv University.

I was on friendly terms with the Latvian Andris Metra. I remember when I was talking with Andris and the Russian Dmitry Kulikov, a Latvian named Kruklinš, who was serving time for non-political reasons, approached us and with a smug smile addressed me, pointing to Dmitry: “This is a katsap, this is your enemy!” To which I replied: “First you identify your enemies, and then you will identify mine.” Andris intervened in the dispute; he came to my defense.

I communicated with Lithuanians, Latvians, Armenians, Georgians, Russians, and Jews. There were few Jews in our camp. They did not enter into any disputes. They understood each other without words. They knew that their hidden goal—the spread of cosmopolitanism among other nationalities—was simply not possible in the camp. And so they were loyal both to the prisoners of different nationalities and to the camp administration. They tried to direct conversations toward the democratization of society, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and the right to emigrate.

When the Russians gathered together, the predominant theme of their conversations was culture. The Ukrainians put the national question first. Everyone wanted what they strived for. The Russians, both during the revolution of 1917 and now, argued that first we must achieve a democratic society together, and then the national question would resolve itself. The revolution did not solve the national question. The empire did not let go of a single nation. On the contrary, it tried to conquer as many countries as possible. Therefore, along with democracy, the national question must be put at the forefront. Each country, having freed itself from occupation, will build a system corresponding to the level of its social and economic development. I was in solidarity with all people of other nationalities in their striving for freedom.

There were many people in the camp convicted for non-political reasons. The operative officer used them. For a pack of tea, he would gather information from them about conversations in the camp. There were fewer “bytovyks” than political prisoners, and therefore their attitude towards us was normal; there weren't even any thefts. If they suddenly saw someone opening a locker that wasn't theirs, you would immediately hear shouts: “What are you looking for in there? Are you a ‘stukach’ [informer]?”

What kinds of stories didn’t circulate in the camp. Outside, not every brain could come up with such things. But they were not gossip, but truths spoken from the depths of a tormented soul. A doctor removed a tattoo saying “Slave of the USSR” from the forehead of one “bytovyk” without anesthesia. When the dead were taken out, the officer on duty at the checkpoint would pierce each corpse with a pike to ensure no living person was hiding under the body. One told how in the camps, when “bytovyks” wore civilian clothes, they were held in zones together with women. A friend of his would come to him, bringing a crust of bread she had managed to hide. They would hide under a blanket and eat so no one would see. Only thanks to this did he survive. Another told how a guard from a tower threw a pack of tea into the zone. It fell just short of the fence. The first fence from the camp was low, so one of the convicts dared to take the tea, stepping over it. He was immediately shot from the tower. That's how the guard earned himself a vacation. Once we declared a hunger strike because a person was killed from a tower for crossing the first wire barrier during the day and stepping onto the raked ground. After three days, having achieved nothing, we went back to work.

I had to serve my term from “bell to bell.”

Analyzing the authorities' struggle with dissidence in the sixties, I came to the conclusion that some of the KGB's actions were inexplicable. To root out the constantly growing “bourgeois nationalism,” the KGB in the sixties of the last century sent a large number of people to prisons, even those who did not deserve imprisonment. The question arises: were the punitive bodies thus trying to prove the necessity of their structure's existence, or perhaps, in the higher echelons of power at that time, were there isolated influential people who had a liberal attitude towards democratic ideas in Ukraine? They understood that in the camps, people were not re-educated, but on the contrary, were hardened, enlightened, and became convinced, nationally conscious individuals. In addition, these processes gained great publicity in their own country and abroad. It is known that the best way to get rid of something is to keep silent about it. And disclosure, even critical, creates popularity and always gives the opposite result. Was it not with the same intentions that the Central Committee of the party distributed Ivan Dziuba's work *Internationalism or Russification?* to all regional party organizations, supposedly for the purpose of condemnation? And let's take the sharp criticism of “bourgeois nationalism” in the press, from which one could learn about the people who were fighting and about the events that were taking place in general. Isn't the result the same? So, probably, the legends about the “Crimson Sails” were not accidental either. Nazarenko says in his *Vyshhorod Legends* that a lecture on Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism was given at the Institute of Communications in Kyiv, in which a lecturer from the Central Committee of the Komsomol claimed that an underground organization called “Crimson Sails” had been uncovered in Vyshhorod, which was preparing an armed uprising. A deliberate exaggeration to add weight. The same lecture was given at the Kharkiv House of Writers. Why was this done, when few people there knew about the Kyiv HPP, let alone the “Crimson Sails”? Why were the KGB's fabrications about a congress of nationalists in Vyshhorod necessary? From all these questions arises one main question: was it their mistake, or was it done deliberately?

I was released on September 17, 1971. Once free, I did not engage in any anti-Soviet activities, but it was not the “Barrel of Diogenes,” as I answered Lukianenko when he asked, “What have you been up to?” when we met in 1989 on Olehivska Street.

After some time, I visited Oksana Meshko and wrote down by hand Levko Lukianenko’s “Letter to I. Vilde,” which I had memorized back in the camp. By the way, I often had to meet with O. Meshko. I helped her with household chores. Then I rewrote this “Letter to I. Vilde” for Ivan Svitlychnyi and left him some of my poems. I asked him to rewrite it in his own hand so that my handwriting would not appear anywhere. After Ivan Svitlychnyi’s arrest, I was summoned to the KGB. There was no talk about the “Letter.” Perhaps it did not reach them. But about the poem “Downpour in the Carpathians,” the investigator, showing it to me in the original, tried to find out who its author was and how it got to Svitlychnyi. He asked me to explain the meaning of these lines:

«На Говерлі здригнулася корона,

Як уздріла гору мертвих тіл –

Це мітла пролетіла червона,

Що розкраяла небо навпіл.

Не злякалися бурі по селах,

Люди в ліс потяглися возами…

Тріснув гнівом наповнений келих

І заплакало небо сльозами».

He asked: “Isn't the poem about the ‘red broom,’ when the Red Army was sweeping German collaborators out of Western Ukraine? And why were people going to the forest with carts?” To which I replied: “In poetry, everyone sees what they want to see. I saw lightning in the ‘red broom,’ and people were rushing to gather hay so it wouldn’t get wet. If you saw something else, that’s your business.” I want to say that symbolism was spreading in poetry at that time, so close to reality that the described real facts spoke for themselves. But no one could reproach the author. There's an anecdote on this topic. A drunk is walking down the street and shouting: “The tsar is a fool.” The police appear: “What are you saying about our tsar-father?” “But I’m not talking about our tsar,” he replied. “Don’t try to get out of it. If he’s a fool, he must be ours.” And they threw the drunk into jail. In such works, every reader clearly sees the criticism of the existing system, but could not reproach the author for this system being the Soviet one. If anyone dared to accuse the author, they would thereby acknowledge that the absurdity of social relations described in the work was Soviet. True, there also appeared those who retouched their essence with symbolism so much that only the author himself could know what the work was about. Such works were not forbidden. The investigator drew up a protocol in which he noted that I could not explain the poem. This casts doubt on my authorship. That’s how you study history from KGB protocols. I refused the offer to work for the KGB. I said jokingly: “You won't make me a general, and I won't be an informer.” At the end of the protocol, he added a non-disclosure statement about the conversation and made me sign it. They didn't summon me to those agencies anymore, but they followed me for several years. And they didn't hide it. Once (many years had passed) the chief power engineer of the baby carriage factory where I worked as an electrician complained that he didn’t know what to write about me to the KGB. He told me how they had suggested he invite himself over to my place with a bottle to find out what my thoughts were.

Before and after perestroika, new thinking, and glasnost, I did not miss a single mass gathering near the monument to T. G. Shevchenko, on the square near the Republican Stadium, on St. Sophia’s Square, and on Independence Square. During the Orange Revolution, I brought food and clothes to the Maidan.

The Orange Revolution won thanks to people’s patriotism. These feelings were deliberately silenced, and are still being silenced today, and the events that took place on the Maidan at that time are being presented as a struggle of clans for power. True, some clans use people's patriotism for their own purposes. Today, one should not bet on personalities. Both Yushchenko and Tymoshenko have many people who cannot be relied upon. If a public figure says that he made the right choice when his chosen candidate won the elections, then this figure has no convictions. His goal is to guess who will come to power, whom to bet on. He is guided by his own ideology, which will later be realized through power and enrichment. It is strange to hear today when the idea is being mulled over: around which idea to unite. Some would like to unite around the idea of destroying the Ukrainian language, around a temporary improvement in life at the expense of losing sovereignty, or perhaps around the idea of destroying Ukraine. But the unification of the Ukrainian people is possible only around the national idea. There is no alternative to patriotism. Ukrainian nationalist-patriots have never placed their nation above others. They only tried to raise their martyr-nation from its knees and place it on an equal footing with other nations. Chauvinists, cosmopolitans, the “fifth column,” janissaries, and biased individuals oppose such an idea.

To build Ukrainian statehood, a strong Ukrainian government is needed. Democratically adopted laws must be unfailingly enforced. Whoever ignores them should be held accountable. If democratically adopted laws are not enforced, it is no longer a democracy, but anarchy.

When all the angles in a triangle are obtuse, it is necessary to change the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. Because it turns out as Tetiana Korobova (correspondent of *Vechirni Visti*) says, that our government has three heads, like the serpent Gorynych. When one head overeats, all three feel sick. Because Gorynych has one stomach, and the government has one Constitution. There is now a threat of losing independence. After the dubious memorandum, when amnesty was declared for the previous government, all anti-Ukrainian forces crawled out of their holes and staged an anti-Ukrainian coup.

After the Orange Revolution, people breathed a sigh of relief, thinking that the struggle for national liberation was finally over. Only social issues remained to be resolved. But, as we see, the struggle must be continued to bring the cause of Independence to its conclusion.

The activities of the Vyshhorod group are almost unknown. In the mass media, for decades, not a single article about dissidence in Vyshhorod has appeared. Only very recently have Oles Nazarenko’s *Vyshhorod Legends* first touched upon these issues.

I believe that the activity of the Vyshhorod group deserves more coverage.

V. O. Kondryukov

December 2006, Kyiv

Edited by V. Ovsiienko on May 28, 2007.

Author's revision on June 19, 2007.

Characters: 45,723