A FIANCÉE’S MEMOIR

Forty-five years ago, we lost Oleksandr Hryhorenko (1938-1962)—a talented Sixtier poet and a prisoner of Soviet concentration camps. On August 18, he wrote me a final letter, which he never had the chance to send. The next day, Sashko died tragically on the Dnipro River.

He came to see me in July 1962 from the village of Borodaivka, in the Verkhniodniprovsk Raion of the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. We met in Kyiv, where I had come from the Vinnytsia region to take entrance exams for the philology department at the Taras Shevchenko State University of Kyiv. I was staying with my aunts and uncle, who owned their own houses in Novo-Bilychi, Sviatoshynskyi Raion.

My acquaintance with Sashko Hryhorenko began by mail. In May of that year, he had read a selection of my poems in *Literaturna Ukraina*, which included a brief introduction by Mykhailo Stelmakh, who kindly supported young poets. Sashko wrote me a letter in response, suggesting we become friends. He also asked me to send him a photograph and some new works, and to meet, if I had no objection.

Sashko’s first letter, with his poems, made more than just a pleasant impression; it captivated me with its special conciseness and clarity of thought. The verses were moving with their frankness, emotional depth, artistic skill, and the ability to speak in a way that not only made you believe but also marvel at his power to engage the reader.

One of them—“To a Desired Fiancée”—I immediately memorized and recited to many acquaintances. Even now, its patriotic sentiments towards Ukraine sound profound and genuine.

Ти мене полюбиш не за пісню.

Ти мене полюбиш не за вроду.

Ти мене полюбиш за залізну

Відданість вкраїнському народу.

Бо й для тебе іншої любові,

Відданості більшої нема,

Бо пісенній придніпровській мові

Поклялась у вірності й сама.

Та коли я душу буревісну

Переллю в живе життя твоє,

Ти тоді полюбиш і за пісню,

І за вроду, вже яка не є.

Indeed, I secretly made my choice: yes, this is my young man, idealizing him for his spiritual, elegant, and multidimensional words. With sweet anticipation, I longed for our meeting.

Oleksandr arrived on the first morning electric train. My aunt Khrystyna woke me. I hastily threw on a housecoat and found myself standing before a tall, slender young man. His straight, thick hair, combed back, fell in dark strands on either side. His gaze was soft and moving. Sashko was somewhat embarrassed for having disturbed us so early. I myself felt flustered. But thanks to the guest's pronounced refinement, our introduction became natural and relaxed. I was getting used to feeling as if we had known each other for a long time and were close friends, although a sense of shyness or some sort of indecision lingered. I even forgot that my guest had just arrived from a journey. Thankfully, my aunt saved the day by inviting us to the table.

Once I had fully composed myself, I looked at Sashko calmly, as if detached. Communicating became much easier and simpler. Whatever he spoke about was not only interesting but also elicited an organic need to listen. He touched on topics of Ukrainian history, literature, the Executed Renaissance, language, and social life. It reminded me of conversations with my father, a village teacher, whose friends—fellow teachers—would gather in the evenings to chat on various topics and play checkers or chess. On holidays, our house would be filled with Ukrainian folk songs. They often spoke of the Holodomor and the widespread repression of the Ukrainian intelligentsia. For us, my brothers, sisters, and me, those hours became a school for understanding life. While seemingly engaged in our own children’s games, we absorbed the adults’ conversations.

Sashko also loved to sing. Not to finish a song was, in his opinion, the same as cutting off one's breath. He had a pleasant voice. When the song was about love, he would look into my eyes, as if confessing his feelings or trying to discover something, to elicit a response. For all my suppressed emotions, he succeeded. My whole soul gravitated towards him, just as the song from his lips gravitated towards me.

I evidently appealed to Sashko. His letter, written to me on the eve of his tragic death, testified to his astonishing and unrestrained feelings. The most striking phrases have stayed with me for a lifetime: “Olenka, no one will love you so selflessly, so self-sacrificingly…”

I kept Sashko’s letters. After I got married, my husband once read them. On the last one, he wrote: “I will win you back, even from the dead...” He must have sensed that my fascination with Sashko, despite everything, continued. Perhaps that is why the letters disappeared, no one knows how. Though there may be more significant reasons for their disappearance. But that is another story.

Sashko's declaration of love was tender, almost dreamlike, yet deep, thoughtful, pure, and bright, without the slightest hint of lust: “Even in my thoughts, I do not permit anything that could upset you. I have cherished and will continue to cherish, as something sacred, my relationship with you…”

Once, whether intentionally or because he truly thought so, he allowed himself an unexpected solemnity: “I love you as I love Ukraine…” After which he watched for my reaction. Seriously and inquisitively, without any hint of a joke. I looked at him, stunned, for I hadn't imagined one could declare love in such a way. It seemed more like pathos than a heartfelt confession. But Sashko enveloped my surprise with tenderness; his gaze compelled me to believe his words. However, he did not resort to similar passages thereafter. For his love for Ukraine, he served a sentence as a 19-year-old youth in the Mordovian concentration camps as “especially dangerous.”

My meeting with his mother, Yevdokia Sydorivna, took place in October 1962. Forty days had passed since Sashko’s death. She came to Kyiv, having arranged beforehand a place where we could be together without disturbing anyone. We wanted, with the help of M. Stelmakh, D. Bilous, or Pianov, with whom I was acquainted, to “knock on the doors” of publishers to finally publish her son’s works, to give him a second life. I know that in those mournful days, I remained for her Sashko's fiancée, about whom he had often told her.

I couldn't get used to the fact that Sashko was gone. The terrible news of his death reached me at the end of September in a letter from my father, who had long hesitated whether to send it by post or to come to Kyiv himself and tell me. The fact is, Sashko's parents didn't know where I was living in the city, so they sent his letter to me and the news of the tragedy to my family in the Vinnytsia region. First, I opened the letter from Dad. In it, he delicately tried to pre-empt my despair. It is difficult even now to convey my shock. Everything before my eyes grew dim, turned upside down… P. 39: So that's why he hadn't written for so long?! And he called to me with the quiet last words of a letter he never sent. On four large pages—pure, most intimate confessions of love, a plea “not to break our sacred agreements for the future.” On a separate sheet—the poem “Ochmariana Myt” [A Befogged Moment], which I still remember.

Sashko's poems were easy to memorize. In them—a passion for life, pain and resilience in the most severe trials, the ache of emotional experiences, freshness of imagery, wonderful rhyme, and rare sincerity.

I read the letter, and my soul was torn to shreds with grief, resisting the terrible news. Could it be untrue? But his mother had written, overwhelmed with pain and tears, that they found her son’s body in the Dnipro on the ninth day. She herself identified him by the birthmark behind his ear. In despair, she screamed and fainted.

And until that moment, she had still held onto hope that perhaps, as the militiamen claimed, Sashko had misled everyone, had disappeared. It would have been better if it had been so. But her son couldn't have done such a thing while she was in the hospital.

I remembered the day of his departure—August 17. We were strolling along the Dnipro embankment, waiting for the steamboat he was to take home, to start his new job in three days. He worked as a construction worker in the town of Verkhniodniprovsk.

“Remember, Olenka,” he told me, “next year I will definitely enroll in Kyiv University.”

At the river station, we went into a café to have lunch. We spoke sporadically, listening to pleasant music. It was then I heard Oginski's polonaise for the first time. The depth of something unusual in the melody affected me so that tears were about to well up. I stood up and headed for the exit, promising to return quickly. Sashko followed me out. We were on the street again, continuing to walk not far from the pier. The premonition of parting troubled us both. To avoid deepening it, as often happens between lovers, he resorted to quoting lines from poems by D. Pavlychko, I. Drach, and V. Sosiura. And he read poems by Mykola Vinhranovsky directly from the collection *Atomni preliudy* [Atomic Preludes], which he had acquired two days before his departure. He marked the half-title page with the date, put my name on it, and gave the book to me. About a year later, Vinhranovsky wrote an autograph in it: “To the girl who believes in the Blue Bird, in the blue sky and in blue eyes—my most wondrous acquaintance, with respect.” I don’t remember on what occasion we—Borys Oliinyk, Svitlana Yovenko, Mykola Som, Petro Zasenko, and I think someone else—had gathered at Volodymyr Pianov’s apartment. It was there I told the author about O. Hryhorenko, that he had been in Dubravlag with Oleksa Riznykov, to which he reacted warmly, as he knew Oleksa from the same school in the town of Pervomaisk. I was advocating for Sashko, trying to get his poems published. So he jotted down in his notebook where and with whom they were located. I don't know if he spoke with Pianov on this subject. We never met again. I went abroad with my husband on a business trip.

...So Sashko entertained me with poems, and I quickly adapted to his optimistic mood. With him, in any situation, it became easy, and above all—interesting. Yes, this is my young man! I mentally rejoiced at the happiness of having such a wonderful and sincere person by my side.

At 3 p.m., the steamboat departed from the pier. Sashko stood on its deck, arms outstretched like a bird. This was how he would greet me with an embrace from afar each time we met. As long as we could see each other, we exchanged waves.

Undoubtedly, the days spent with Oleksandr were beautiful. I thank God for granting me the happiness of such meetings, for a friendship that truly blossomed into deep feelings.

Sashko was a person of exceptional inner beauty, a strong-willed individual, always full of spiritual balance and purpose. Remembering him, I can't help but feel that he seemed to have done everything to be remembered brightly. In one of his poems, he wrote just that:

О, тільки б вічно невгамовним

вриватись в людськості життя,

щоби по смерті морем повним

в чиїсь улитись почуття!

The writer Mykola Kucher, who was imprisoned in the same zone with Sashko, writes in a letter to Yevdokia Sydorivna: “I feel guilty before you and before Sashko because after his death (I found out about it about two weeks later) I did not contact you and did not come to the grave of my friend, not only in misfortune but also in spirit... And then suddenly, in Dniprodzerzhynsk, I buy the book ‘Vitryla’ [Sails], I open it—and Sashko's intelligent eyes look at me. It’s hard for me to convey what I felt at that moment... I wanted to cry and at the same time I rejoiced that this person dear to me was among the living.

I know, Yevdokia Sydorivna, that your grief is great, but I want to assure you that all who knew Oleksandr will never forget him. He was better than all of us. Talented, honest, uncompromising, and at the same time a simple village boy...”

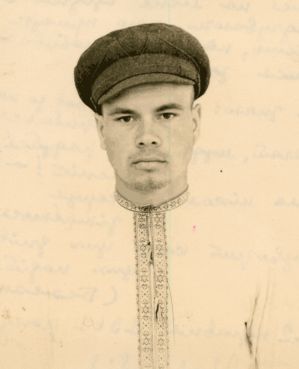

A few of O. Hryhorenko's poems, with a foreword by his mother, were published in the almanac *Vitryla* as late as 1967. And only after she sent a desperate letter to Volodymyr Pianov, to whom the manuscripts and a photograph had been given five years earlier.

...A day later, Yevdokia Sydorivna and I left for Borodaivka. Upon arrival, we went to the cemetery. A wooden cross stood on Sashko's grave; marigolds and asters, planted by his mother already in bloom, were flowering. Near the cross, among the flowers, was a portrait of the poet in his cadet uniform. The same intelligent, clear eyes looked at me. A silent conversation took place between us...

His parents, Yavtukh Antonovych and Yevdokia Sydorivna, told me about all the periods of their son’s life. From the age of thirteen, Sashko wrote proper poems, sending the best ones to the newspaper *Zirka* [Star], from which he received favorable reviews and advice. Teachers called him a great dreamer and romantic. From the fifth to the tenth grade, he was the editor of the school newspaper and was a good student. He early recognized himself as a poet. In the seventh grade, he dreamed of becoming an artist; in the upper grades, he decided to be a military man.

Having received his high school diploma, Sashko enrolled in the Vasylkiv Air Technical School. He soon realized that this did not match his inner calling. Since childhood, he had not liked to complain about anything, but this time he couldn't bear it and wrote to his parents: “The work doesn’t scare me, it’s just bad that there is little free time, and I am now forced to abandon my favorite pastime—writing poems. Almost everyone here speaks Russian, even some Ukrainians. I want to preserve the purity of my language, I don’t want to yield to Russian influence…” He was probably preparing his relatives for the fact that a military career was not for him. He dreamed of a philological education. A few months later, he submitted a resignation report to the school’s commandant.

In the spring of 1957, Sashko returned home and actively prepared to enter the university’s language and literature department. But these plans were not destined to be realized: the district military commissariat handed him a summons to the army. He was sent for compulsory service to Azerbaijan, to the city of Qusar. In the army, he wrote poems on various themes, but mostly about the fate of Ukraine and his love for it. He sent them to the editors of Ukrainian periodicals and in the evenings read them to fellow servicemen from his region to hear their opinion.

As his parents were convinced, Sashko did not know that a secret dispatch had been sent from the Vasylkiv school to the military unit where he was serving, instructing them to keep a close watch on the boy, as he allegedly liked to write forbidden things… And someone, probably, was monitoring him and then dutifully reported to the political department of military unit 54815 that national-patriotic sentiments dominated Sashko’s poems. His fate was decided quickly: a search, arrest, investigation, prison, and a concentration camp in Mordovia. For six years.

In the summer of 2006, Oleksa Riznykov—a writer from Odesa—and I visited the village of Borodaivka, the graves of Sashko and his p. 40: mother. In Zhovti Vody, where the Hryhorenkos' eldest son, Hryhoriy Yavtukhovych, now lives, his father, Yavtukh Antonovych, is buried. We also laid a wreath of flowers on his grave, thus paying tribute to a man of a suffering fate.

In Borodaivka, pensioner Serhiy Chmil—a school friend who also served his compulsory military service in Azerbaijan—shared his memories of Sashko.

“He was conscripted in the spring of 1957, and I was in the autumn of the same year. We served in the same battalion, but in different companies. We sometimes met, shared news from home. About three months later, I see two soldiers leading Sashko in handcuffs. He greeted me: ‘Serhiy, take care, and—goodbye! We won’t see each other soon…’ He was serving as a lieutenant for special assignments at the headquarters. I thought maybe he had done something wrong. I learned from the guys that they found some poems in Sashko’s bedside table, a letter from a friend in Kharkiv, supposedly a member of a secret society of like-minded young writers. I knew Sashko had been writing poems since school. As soon as he was arrested, they also conducted a search at his parents’ house—my relatives from home informed me. The investigators dug up the entire garden. They found nothing.”

Yevdokia Sydorivna showed me Sashko’s high school diploma. All fives in humanities, no threes at all, excellent conduct. She also produced a certificate: “…issued to Hryhorenko, Aleksandr Evtikhievich…, sentenced by the Military Tribunal of the Baku PVO District on January 16-17, 1959, under Art. 72, Part I of the Criminal Code to six years of imprisonment…” It also mentioned that the six-year prison term was reduced to three years. This was evidently explained by Khrushchev’s “thaw.” Sashko was released from the correctional camp on October 1, 1961.

Both Yavtukh Antonovych and Yevdokia Sydorivna, speaking of Sashko, complemented each other, proud of his talent. But there was no consolation for their grief. So they lamented that they had raised their son to be a real man—honest, sincere, and principled.

From Yavtukh Antonovych—a man of an astonishing fate—I heard how he was taken as an Austrian prisoner during World War I. He returned several years later. In 1932, he was entrusted with managing a collective farm. Two months later, for failing to meet the state grain procurement plan, he was repressed and sent to Siberia. There he met his second wife—Yevdokia Sydorivna, whose family had been dispossessed as kulaks. Her first husband died in an Arkhangelsk prison, and their two small children swelled from hunger in a stranger’s house. Their mother learned of this when she returned from exile to her home in the Poltava region.

Yavtukh Antonovych’s wife also died of starvation, leaving two children, Nadia and Hrysha, as orphans. His elderly mother cared for them. Yevdokia Sydorivna replaced the orphans’ mother. And in 1938, a son was born to the newly formed family, whom they named Sashko.

During World War II, in 1943, Yavtukh Antonovych fell into German captivity. He returned four years later. And again he was repressed. Over sixteen years were erased from his life. Yavtukh Antonovych began to write his memoirs for posterity. Sashko knew that his father had taken up writing his memoirs. Whether they were written and who possesses them today is unknown. They may have been confiscated by the KGB during a search.

Thus, in the evenings, in my presence, Sashko's parents shared their difficult stories about him and about themselves—hostages of a totalitarian regime. They spoke of exceptionally courageous things, about each one individually. My heart ached with inexpressible sorrow. How could this have happened, Sashko? Why didn't you protect yourself?

Yevdokia Sydorivna often turned the conversation back to my meetings with their son, to that last unsent letter to me, and to Sashko’s return from Kyiv to Borodaivka. Then, upon crossing the threshold of his home, he had joyfully exclaimed: “That’s it, Mother, I’m getting married!..” She seemed to be trying to clarify something, recounting the contents of Sashko’s letter.

“There, my child, it was about your plans for the future, about my son's feelings for you,”—and she would fall silent, picturing in her mind something that might, perhaps, just a little, assuage her maternal grief.

And once, taking my hands in hers, with her inherent village politeness, she asked delicately:

“Olenka, perhaps you are carrying Sashko’s child? I will beg you—give birth to it…”

A hot wave washed over my face. The question was indeed completely unexpected for me. It could have concerned anyone, but not me. Not my innocence and sense of responsibility, nor Sashko’s nobility, who protected me from such frivolous “romantic adventures” and could not even in his thoughts allow himself “something like that…”

You should have seen the hope in her eyes, the anticipation… I looked at her, embarrassed and compassionate, not knowing what to say. But in my soul, I regretted that it hadn't happened: not only to please the grieving mother, but also for the sake of my passionate love for Sashko.

Mykola Kucher, whom I mentioned earlier, also knew about our serious plans for the future. In his essay about Sashko, “Arise, Poet, Arise!,” published in several issues of the Verkhniodniprovsk newspaper *Prydniprovskyi Komunar* [1993], I read: “Once, in the spring of 1962, I was walking down a street in the village of Dniprovske past a house whose construction was not yet finished. Suddenly I heard someone asking me to wait, and a moment later Sashko Hryhorenko, tanned by the sun and in cement-stained clothes, ran out of the building. We embraced like brothers, moved by the unexpected meeting. It turned out that Sashko had had some luck: his prison sentence was reduced by another year and he had returned to his native Borodaivka in the autumn. He was working in construction, dreaming of studying at Kyiv University. If not this summer, then the next he would definitely submit his application. Kyiv attracted Sashko not only with its university but also with its poets. He was already corresponding with two poets, Mykola Hirnyk and Mykola Som, had sent them his poems and received a favorable response…

He also told me that he had met a young poetess from Podillia, Olena Zadvorna. Sashko liked her poems and her herself. He hinted that their acquaintance might grow into a friendship, and then into something more…”

Sashko eagerly “dragged” me through the museums of Kyiv. And we walked the Dnipro slopes from end to end. Our conversations were about the future, about literature and the Ukrainian language. By the way, he knew several languages—English, German, French, and Polish. He spoke the latter fluently, but the others, according to him, needed better pronunciation practice. I also speak Polish quite well. So sometimes we “mixed” Polish words into our native lexicon.

I know that Sashko admired the poetry of V. Bryusov. He adored it, wrote poems about the poet. I first met him with a volume of Bryusov on the courtyard of the house in Novo-Bilychi. In a rebellious and angry letter, written on August 18, 1962, and not sent for the same reasons as mine, to a Kyiv editorial office, Sashko aptly mentions his beloved poet: “I no longer ask for forgiveness for my persistence. Without any awkwardness, I inform you that I am enraged, that I am outraged by your behavior towards me, and in such a state, sentimental politeness is inappropriate. The runaround with my poems has been going on since December of last year. And I will not bow, I will not put my soul on its knees. As a child, I knelt before an icon (that later fell away); now I bow before the magic of Bryusov…”

I would like to quote another excerpt from the letter: “Why am I not being published? Could the Mordovian ‘stains’ be the cause? Huh? That’s most likely… Why is this so? Well, so what if I have a ‘past,’ so what if I was ‘unreliable.’ So what, should I hang myself, or what? I don’t write anti-state poems. Or maybe I should resort to hymns and odes? No. I am too intelligent and hon- p. 41: est to just sing praises, ‘as in the good old days.’ So advise me how poems are crafted now, and maybe one day I too will strike a false note. Aren’t we cut from the same cloth?”

This letter contains only the poem “Horinnia” [Burning], quite perfect, ready for publication in the most demanding editions.

I have reread Sashko’s works several times, copies of which Oleksa Riznykiv sent me from Odesa. The poems are worthy of being published before they are completely lost in the drawers of “indecisive” publishers. We must collect everything written about O. Hryhorenko, supplement it with new memoirs, and publish a book by the Sixtier poet who never became one in his lifetime. Although he had an undeniable right to it—for his absolute patriotism, for his poems imbued with love for Ukraine, full of sorrow over its subjugated fate. For the fact that the Bolshevik-communist regime took his best years, branding the poet’s path to the people. Ultimately, for the poems that investigators and judges interpreted as nationalist and anti-Soviet.

It is known that three of O. Hryhorenko’s prose works have been lost somewhere in manuscript form: “Povernennia” [The Return], “Mandrivka v yunist” [A Journey into Youth], and “Vesniani bazhannia” [Spring Desires]. These must also be found and published, by which we will pay him a just tribute. And people will know the truth about those times when the best sons and daughters of Ukraine suffered the greatest oppression from the totalitarian regime.

In my home library, I have volumes of I. Franko, L. Ukrainka, M. Kotsiubynsky, O. Storozhenko, S. Vasylchenko, P. Hrabovsky, and B. Hrinchenko's 4-volume dictionary, all purchased by Sashko in Dubravlag, with the inscription on the half-title page “Hryhorenko Oleksandr, 14th, 3rd camp (Mordovia).” Yevdokia Sydorivna wanted to give me all the books her son had used. I took only a few as a keepsake. So that each time I could feel Sashko’s touch on them, to stir in my memory something secretly tender and moving, known only to us both. My meetings with Sashko Hryhorenko are like flashes of a bright star. And not because they are accompanied by such a tragic conclusion. Not at all. How to convey his amazing quality with the best words! But then again, perhaps it is not necessary. After all, his poetry, preserved by good people, exists. There we will find and feel the full picture of Sashko’s existence with all his feelings for a world in which he was not always comfortable.

Remembering O. Hryhorenko, I can clearly picture every line on his face, his kind, intelligent eyes, and his smile. I hear the wondrous strings of inspiration and a great love for life ringing in the Poet's heart.

Olena ZADVORNA-HALAI,

Teacher of Ukrainian Language

and Literature, Lyceum No. 157, Kyiv

Oleksandr HRYHORENKO

ХОЧУ

Я хочу, сонце щоб світило,

Я хочу, вітер щоб зітхав,

Я хочу, струни щоб дзвеніли,

Щоб дзвону спів не затихав.

Щоб серце чуле і тривожне

Було у кожного з людей,

Щоби зробити було можна

З дорослих грішників – дітей.

Щоб совість щира, незрадлива

Суддею кожному була,

Щоби ніколи кривди злива

Ростків добра не залила.

Хай вільно будуть дихать груди,

Хай щастя ллється із очей,

Ніколи хай не будуть люди

Тіснить подібних їм людей.

25.05.59 р.

МАТЕРІ

Рідна мамо, плач душі моєї

Ти одна лиш в змозі зрозуміть,

Як щодня бажаю я зорею

В рідний край з неволі полетіть.

І щодня душа моя ридає,

Хоч в очах нема ані сльози.

І щодня вразливо відчуваю

Над душею темний гніт грози.

Боляче дивитись на наругу.

Боже! Кривдять брата без жалю,

Кров’ю серця ллється моя туга,

Бо чесноту, нене, я люблю.

Рідна мамо, ти мене не бачиш,

Та мої прогірклі сумом дні

Ти відчуєш серцем і заплачеш –

І в той час полегшає мені.

18. VIIІ/60 р.

ЩОДЕННО

Дні потихесеньку чвалають,

Здається, краю їм нема.

О, швидше, дні, – я тут конаю,

Там руки матінка лама.

Вже недалеко заповітний

Мій день останній, перший день.

О, скільки в серці зійде квітів,

О, скільки вирине пісень!

Але як тихо дні чвалають,

Повільно як минає час.

І думка чадом нависає,

Що ти давно уже погас.

16. VII. 61 р.

ОЛЕКСІ РІЗНИКОВУ

В краю чужім звела нас доля,

Мабуть, для того, щоби ми

Сказали людям правди голі

Й самі зосталися людьми.

І ми йдемо шляхом чесноти,

Йдемо без гімнів і без од,

Щоб нам не міг очей колоти

За лицемірство наш народ.

У світ письменства, світ строкатий

Ми переступимо поріг

І мусим те удвох сказати,

Чого до нас ніхто не зміг.

Щоб наше серце променисте

До читача могло дійти,

То мушу я творити змісти,

Творити форми мусиш ти.

Слова незвичні, дивні теми,

Не чута досі гострота –

Хай все це з віршу, із поеми

У душі людські заліта.

І як би деякі не злились,

Нам будуть слати і хвали,

Бо, друже, так уже судилось,

Щоб ми поетами були.

Та не забудь, що в дні похмурі

Звела нас доля, щоби ми

Були в своїй літературі,

Крім всього, чесними людьми.

21. VII. 61 р.

ДРУГОВІ ПАВЛОВІ ФЕЛЬЧЕНКУ

Як хороше, що б’ється десь на світі

Таке гаряче серце, як твоє,

Яке добру й чесноті геть відкрите,

Якого зрада ввік не обів’є!

Як хороше, що ти існуєш, друже,

Що козаками прадіди були,

Що в нас проснулась воля їхня дужа,

Що ми від них по духові орли.

СПІВВ’ЯЗЕНЦІ

Я не знаю, хто ти, що ти, звідки,

Ти не знєш, в’язенко, мене.

Та – життя пощербленого свідки –

Ми з тобою думаєм одне.

Із чийого роду ти – не знаю,

Та твій «добрий ранок» розказав,

Що тебе взяли із того краю,

Де блакить, біленькі хати, став.

І з бентежним серцем, з хвилюванням

У тобі побачив я сестру.

І сказав, що днів цих безталання,

Зустрічей із серця не зітру.

Від предивних марень весь я тану,

Що ж, нехай і табір – не біда,

Може десь за зубцями паркану

І моя страждає Сигида.

6. VI. 61 р.

Olena Zadvorna-Halai. A Fiancée’s Memoir // magazine “Ukrainska Kultura,” No. 8 (971), 2007, August. – pp. 38–41. (Also includes a selection of six poems).

Photos from 2.05.1958 in the army; 22.05.1961 in captivity.