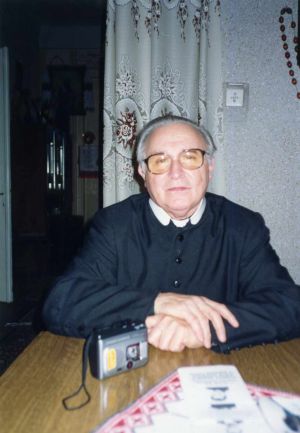

Memoirs of Father Josaphat KAVATSIV

I, Josaphat-Vasyl Kavatsiv, son of Mykhailo and Varvara, was born on January 5, 1934, in the village of Yablunivka, Stryi Raion, Lviv Oblast, to a working-class family. My father was a worker, and my mother a peasant. My mother came from a very devout and large family. My maternal grandmother was very religious, a zealous churchgoer who belonged to the Brotherhood of the Sacred Heart and had a rather large church library at home, where, according to my mother’s stories, people would gather at their house to read devotional books, as the children in my mother's family were educated and religious. My late grandmother very much wanted someone to dedicate themselves to a monastic, priestly life, but somehow it was not meant to be. My mother and my aunt wanted to enter a monastery, but for some reason, they did not. My uncle, my mother's brother, studied at the theological seminary in Lviv but did not become a priest. My grandmother went to church every day and received Holy Communion, and she must have prayed for the grace for me, her grandson, to fulfill her wish and dedicate myself to a monastic and priestly life. All who remained on my mother's side of the family were repressed by the Stalinist regime.

My mother instilled in me a great love for God and the Church. From a young age, I grew to love the Church. Sister-Superior Yoanykia in the city of Stryi instilled a great love in me, and I shared my thoughts and views with her. She was very fond of me and cultivated in me a great love for the monastic life.

Then came 1946. The year our holy Greek Catholic Church was liquidated.

Our family, on my mother's side, was among the first to stop attending the Russian Orthodox Church, right from the day the liquidation of the Greek Catholic Church was proclaimed. Since 1946, neither my parents nor I have ever attended the Russian Orthodox Church. Despite this, my heart yearned to serve God and the Church. Difficult times came for Greek Catholics. There were very few of us, yet we somehow believed in victory and the legalization of our Church. We, Greek Catholics, were subjected to great trials and ridicule from our fellow villagers.

Throughout my youth, I thought of becoming a priest of such a martyred Church to help my long-suffering people. The times were exceptionally difficult and bitter. There were no prospects of becoming a priest, yet my heart longed for the monastic life, and specifically for the Basilian Order. In my free time, I would stay with the nuns. I prayed with them, meditated, and learned what they knew.

I had a lot of trouble at school because I refused to join that wretched Komsomol, and fortunately, I never was a member. The KGB agencies took an interest in this because I was conducting agitational work at school, urging others not to join the Komsomol.

One time, there was a forced enrollment campaign. They took all of us to the Komsomol raikom (district committee) by force. Everyone signed up except for the three of us, but I jumped out of a second-story window and escaped from the raikom. This caused great trouble for my parents, especially my father, who worked as a mechanic at the Uhersk alcohol distillery. They terrorized him, threatened him with arrest, and eventually dismissed him from his position and transferred him to the job of a stoker. Naturally, I had a lot of trouble at home from my father, because at first, he didn't really want to understand me. My mother and her entire family were always in solidarity with me.

After finishing the 10th grade, I graduated from a finance and credit technical college and was assigned to work at the Zhydachiv Paper and Cardboard Combine as an accountant in the settlement department, where I worked until 1957. In Zhydachiv, I expanded my work among Catholics, as there were many of them there at the time, and they all loved me boundlessly. We would all gather at my apartment for evening prayers, secretly, because I had the Most Holy Mysteries at home, and many of my like-minded friends, like myself, received Holy Communion on their own every day, as there were no priests. At that time, there was only Father Kliuchyk, OSBM (Order of Saint Basil the Great. – V.O.), and Father Moliarchuk; all the others were in prisons and camps.

I helped His Beatitude Josyf Slipyj a great deal by going around to Greek Catholics in the evenings and collecting whatever they could offer as a donation. And the times were very difficult; one couldn't even afford to buy bread. I packed all of this into boxes and sent them to His Beatitude Metropolitan Slipyj, Father Shabak, Father Taras, the Sister Servants, and the Basilian Sisters.

All this was uncovered, and in March 1957, I was arrested for the first time, but there were not enough witnesses. This was arranged for me by a deacon from Drohobych named Savchuk—that’s what I seem to remember—and a priest from Zhydachiv named Triafechuk, who wrote denunciations to the KGB about me, stating that if I were not removed from Zhydachiv, they would write to Moscow.

On April 7, I was released from custody, fired from my job, and evicted from Zhydachiv within 24 hours. It was very hard to find a job; no one wanted to hire me. I was threatened with prison for “parasitism,” and after great difficulty, I got a job at the DOK (wood-processing plant. – V.O.) in Stryi, carrying wood away from the machines. The work was very hard and humiliating: from an accountant in the settlement department to the lowest-level job. The KGB dragged me in for various interrogations every two or three days, both at the KGB and at the DOK's personnel department, where they had made an entryway for themselves.

This continued until 1960. They wrote various feuilletons in their mendacious newspapers; for a whole month, I was featured as a caricature in the entire display window of a grocery store in Stryi, along with Father Levytsky, a canon of the Lviv chapter and my confessor, whom I greatly respected and loved. In a word, there was enough of everything to drive a person of my age at the time insane. I held on, but because of this, my faith was strong, and I prayed a great deal. Perhaps I do not pray as much now due to the duties of my station, but my heart always yearned for the priesthood. I studied and prayed.

In 1954, our priests began to return home from prisons and exile. Many priests came to visit me, especially Father Velychkovsky, later a bishop, and Father Mysak, also later a bishop. They were also Redemptorists who treated me well and wanted me to join their congregation, but my heart was set on the Basilian Fathers. I knew Father Shaban, Father Roskop, and Father Kliuchyk well—they were Basilians—as well as Father Roman from Sambir, Father Protsiv, Father Shepitka, and many other Basilian fathers.

The Father Protohegumen also returned from the camp. I went to him with my intentions, and in his kindheartedness, on December 22, 1954, he allowed me to take monastic vows. This was an endless joy and happiness for me. The Father Protohegumen entrusted me to Father Pakhomiy Borys, who became the Protohegumen after his death, and he became my spiritual guide, superior, and everything. Under his guidance, I made my monastic profession and became a full-fledged monk of the Basilian Order. At that time, I was studying theological sciences. The one who helped me the most and was my professor was Father Dr. Yeronim Tymchuk, who probably invested the most of his efforts and skills into my young monastic heart and soul. He was an exceptionally intelligent, kind, and quiet person who never spared his time for me, as the professor was preparing me alone for the priesthood. It was difficult because I had to work during the day and study and take notes in the evening.

At this time, I left the DOK and was hired as a stoker at School No. 10 in Stryi, and later as a building manager at School No. 2, thanks to the kindness of Mr. Petro Mepesh, the school director, who was like a father to me. But it did not last long, as he was soon dismissed from his directorship, and Bohuslavska, the wife of the city's mayor, became the director. She was unfair to others and everyone feared her, but for some reason, she liked and respected me, and I held two positions: building manager and accountant-clerk, although the salary was very meager, 35 karbovantsi for all positions. My professors were Father Dr. Maksymets, a professor of philosophy, Bishop Fedoryk, Father Bohun, Father Kliuchyk, Father Borys, and a few others, who instilled much good in my mind so that my wish could be fulfilled and so that Bishop Slyziul, the Ordinary of Ivano-Frankivsk, would lay his hands on me, as I was ordained on May 24, 1962. The joy, of course, knew no bounds. What I had wished for was fulfilled in me.

Father Protohegumen Pakhomiy did not really want me to start working immediately, so as not to betray and expose the bishop, but my heart always yearned for pastoral work. Everything was supposedly clandestine, but that same year, on the Dormition of the Mother of God, I celebrated the Divine Liturgy in Sambir at the Sister Servants' convent, and in the evening, I arrived in Lviv and had a Divine Liturgy at 12 o'clock at night on Kuznetsov Street. I was returning late to the Yachminsky home, where the Sister Servants lived, when the Druzhnynnyky (volunteer police) and the militsiya caught me at night. They took all my belongings, and I had a lot of trouble. Afterward, for 10 years, all the press outlets, at all conferences and all meetings, wrote that I had been caught in Lviv with illegal literature. I resigned from School No. 2 and transferred to work at the Teacher's House in Stryi, where I headed the trade union as an accountant. My director was Romaniuk, now a deputy of the Verkhovna Rada. We worked well together, as we always found like-minded people. At the direction of the Father Protohegumen, I was forced to leave my parents and move to Lviv. They wouldn't register me anywhere.

At first, I registered in Lisnovychi, Pustomyty Raion, but after 6 months I was de-registered, even though I lived in Lviv. The KGB ordered me to leave Lviv. Then I registered in Rudno. After 1 month, I was de-registered again, and I registered in Yavoriv Raion, but after 5 weeks, I was de-registered again, and I registered in Sukhovolia at Mr. Kucherka's place. I was de-registered and was left “hanging in the air.” And each registration cost 700-800 karbovantsi. I went to Moscow 7 times regarding this matter and wrote 24 complaints to all authorities, but it was all in vain. Finally, I wrote to the newspaper *Izvestia*, and they ordered the prosecutor of the Horodok Raion to investigate. Through good people, a way was found to him, and he decided to register me there for money—1,000 karbovantsi.

All these de-registrations took place because, from the first day of my ordination, I began to work actively in the field of the Greek Catholic Church as an underground priest, but on two fronts: secretly in homes and by starting to open churches that were closed and de-registered. The first of these churches was the Church of the Intercession in Lisnovychi, Horodok Raion. It was a small, wooden church on the edge of the village, on the western side. To get to this church, one had to travel to Kaminobrid and then walk 9 km through knee-deep mud. Because of this, every Sunday and holiday, there was a multitude of people from the surrounding villages who came for the services. The ordeal was great, as was the joy of being able to serve the people.

I worked in 78 villages and cities, such as Stryi, Yablunivka, Dobriany, Lysiatychi and Zhydachiv, Khodoriv, Zavadiv, Holobutiv, Nezhukhiv, Kolodnytsia, Dulyby, Lanivka, Railiv, Haii Vyzhni, Haii Nyzhni, Drohobych, Doroniv, Dolishnie, Morshyn, Dashava, Kovska, Vivnia, Piatnychany, Phany, Vilkhivtsi, Volytsia, Tserkivna, Lviv, Zymna Voda, Rudna, Sukhovolia, Mshany, Lisnovychi, Lisnevychi, Moloshkovychi, Berdykhiv, Pidtupy, Muzhylovychi, Cherchyk, Kohut, Novoyavorivsk, Shklo, Lisy, Hradivka, Dobriany, Rydatychi, Chornokuntsi, Chulyn, Yavoriv, Kalynivka, Lozana, Prylbachi, Trukhaniv, Bubnyshche, Hoshiv, Dolyna, Bolekhiv, Dovroluka, Kamianka-Buzka, Kolodychi, Kolodne, Zhovtianytsi, Lutsk, Kyiv, Moscow, Leningrad, Stryi, Zvyzhen, Beryshkivtsi, Ivano-Frankivsk, Nadorozhna, Horodyshche, Kolomyia, Hrabivtsi, Mokhnata, Voloshcha, Ternopil, Sambir, Luzhok, Zaluzhany, and other villages that are hard to recall now. Almost all of this was done at night, because during the day I had to work at a state job, and at night I had to travel for underground work. Sometimes someone would stand in for me, but mostly I had to take care of it myself. The work was hard. Nighttime confessions, weddings, funerals, baptisms, Divine Liturgies, and all other services needed by the faithful Greek Catholics. The work itself is one side of the coin, but the biggest side was the fears and denunciations from the Orthodox priests of the Russian Orthodox Church, who reported on the illegal services of the faithful to the authorities every month and every quarter. What I had to endure from these denunciations is beyond words, but praise be to God, and the good of the faithful always came first for me, and there was no force that could pull me away from it. The KGB agencies watched me terribly and had their people in almost every village and city, who reported everything. It was calmer and safer in private homes, but then few people benefited. But in the churches, there were multitudes of people who benefited, and for me, that was a joy and satisfaction. One could write histories from almost every month listed, because I had to arrive in each village almost at night, with the exception of a few villages where I allowed myself to travel during the day because there were no informers there. The work was immense, very immense. I want to describe some of the larger villages that I remember well and for which I later had to suffer, namely the village of Mshana, the village of Muzhylovychi, Berdychiv, Zavadiv, Kolodytsia, Kolodiantsi, and some other villages that became very dear and memorable to me.

Muzhylovychi, Yavoriv Raion. I arrived for the first time on the feast of Saint Nicholas and found the people themselves conducting a service, singing the Divine Liturgy, somewhere around the “Holy God,” in an old church built about 600 years ago. They received me very cordially, but they knew very little about the Catholic Church. Some priests had visited there, but only sporadically, and they taught the people very little. An Orthodox priest sometimes conducted funerals, but he loved vodka and gave much to sinful people. I earnestly set to work and, as usual, began with the Most Holy Eucharist, teaching the people to confess and receive Communion frequently. Almost everywhere I worked, I had and still have a great many people who practice daily Holy Communion.

Then there were troubles because I couldn't manage the people, as everyone wanted to go to confession. I practiced, and in many villages held, novenas to the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, that is, receiving Holy Communion and making a holy confession for nine consecutive Fridays. People liked this very much, as many people, both men and women, completed such novenas. In Muzhylovychi, I had great success because for some reason everyone there grew very fond of me, even though I am quite strict and demanding, both with myself and with others.

There were so many people every Sunday and holiday that there was no room to accommodate them. On warm days, all services were held outside under the open sky, because many people from other villages came and traveled for the services, but on unfavorable days it was quite difficult.

Next to the old church stood a new church, built in 1928, but it had large cracks, and they had stopped building it. It was filled with a pile of garbage that jackdaws and crows had brought in over all those years. The thought came to my mind: why not clean out this church? At least it wouldn't be under the open sky, but inside, even if it had no doors or windows and everything leaked, at least the wind wouldn't blow. I advised them to do it. They spent two Sundays hauling out the garbage and filling all the nearby ravines. They cleaned it, covered the windows with plastic wrap, lined the walls with paper, set up an altar, and began to pray there for two years. Afterward, they consulted with specialists and, at a time when it was impossible to pray in the church, they set about completing this sanctuary. They reinforced the perimeter with cement, that is, with a solution from a construction combine, as many people worked there. They found two pits of lime that had been in the ground for 70 years and began the work. Every day, 50 hired people, both women and men, worked on the vaults. In a word, after 11 months of diligent work by the people, everything was done, and I had to be there two or three times a week to oversee it, as everything required consultation. The work was humming. This work was managed by Mr. Nakonechny and Mr. Yaremiy, both now deceased. Five altars were built: the main altar, the Altar of the Heart of Mary and the Heart of Jesus, the Altar of Saint Joseph, and the Altar of Saint Josaphat.

I brought many statues from Lithuania at my own expense.

On the feast of Saint Michael, the patronal feast day, the consecration of this church took place. It was a triumph. In the Brezhnev era, in a time of persecution and oppression, a new, beautiful, stone church appeared.

The head of the executive committee, Ivanchenko, knew all about this but remained silent. Later, when I was already in the camp, they wrote to me that he had committed suicide because someone recognized him as a former member of the SS. He was afraid and hanged himself in his bathroom at home. He was a good man whose silence helped us a great deal.

The consecration was held ceremoniously. A few days later, a commission arrived from Kyiv, from Lviv, God knows from where, because someone had written that the Uniates had built a church. This, as people said, was Shevchuk, a fellow villager. His daughter was a zootechnician and later the head of the village council. No one let the commission into the church.

On Holy Eve, that is, on the Epiphany, the KGB took me from Lviv. They brought me to Yavoriv, where the entire party elite was gathered. Ivanchenko, the prosecutor, the head of the KGB, the head of the militsiya, and many other people who interrogated me all day, from morning until 8 o'clock in the evening, about the construction of the church. Of course, I didn't tell them anything specific, but it was all preparation for my arrest.

Another such active village was Mshana in the Horodok Raion, where I worked a great deal, almost every Sunday and holiday. During this time, I had to celebrate almost 5-6 Divine Liturgies in one day, plus a moleben and a sermon. Transportation was very difficult, as I didn't have my own car, and I always had to pay and ask someone to take me and bring me back. The church in Mshana dates from 1700, but it had no floor, and when I arrived, there were grates there; the church was dirty and in disarray. I borrowed 10,000 karbovantsi in Lithuania, we bought tile, laid a beautiful floor, and did repairs. That is, I had the church painted at my own expense. Perhaps the people would have reimbursed me some of it later, but on the patronal feast day, December 4, the Presentation of the Most Holy Theotokos in the Temple, a solemn consecration of the church took place. I left my belongings and a beautiful monstrance there, and on December 8, 16 militsiya vehicles with dogs and the KGB surrounded the church and completely destroyed it. The iconostasis and altars, the pulpit, and the confessional icons were taken to Horodok and set on fire, and the main altar was destroyed. And one of these “bandits” even defecated on the main altar. We did everything we could, wrote everywhere we could; a delegation went to Moscow and Kyiv more than 20 times, but it was all in vain.

Justice was nowhere to be found. They brought unusable television tubes to the church and made it a warehouse for junk. We began to pray outside the church. The situation was very difficult. Cold, wind, frost, snow, and in the summer, scorching heat. It was mostly done at night, occasionally during the day, but still, we did not give up.

I remember that during many services, the rain poured down for the entire service, so that there wasn't a single dry thread on me; I was soaked as if in water. When services were held at night and in winter, the winds howled so fiercely, because the church was located outside the village, completely outside the village, that not a single candle could stay lit. And there were always many people for Holy Communion, so one of the boys had to shine a flashlight so I could give communion. My good fortune was that I knew everything by heart, and still do to this day, and I never needed a book or light. The people suffered greatly, I suffered greatly, but at that time there was a great zeal for the faith. Dozens of times I had to walk from Mshana all the way to Rudno, where I lived for several years, because there was no transport, and the train didn't come until morning, so I always had to walk, in good weather and bad. One didn't think about it then, but one was always fortified in spirit that the people had benefited from the service.

Well, one could talk a lot about Mshana and about those good people, like the Mykhailyshyn family, who worked the most for the good of the church.

Then again, there was the village of Zavadiv in Stryi Raion. It was very difficult to work there because the head of the village council was Myron Berezretsky, who lived in Holobutiv, which was also my parish. But most of the services took place in Zavadiv, sometimes in homes, but on Sundays and holidays, always at the cemetery.

As soon as you arrived at the cemetery, within 15-20 minutes, Berezretsky with the KGB, the militsiya, and the druzhynnyky would be there. He was a terrible man, and it seems to me that no one gave me as much grief as this Berezretsky, who is now a great nationalist and even a member of Rukh. An opportunist and a "scoundrel"—I can find no other word for him. In addition, he testified against me at my trial.

And how much effort it took to celebrate a service in Trukhaniv, Skole Raion. Living in Lviv, I had to travel to Tysmenytsia, and from there walk to Trukhaniv on a gravel road, amid the winds of the Carpathian mountains, rains, and bad weather. Sometimes I couldn't even make it to the house, because it was very far.

I took the needs of the people to heart; I could not refuse anyone. Almost everywhere I had to hear the confessions of the sick and the healthy, perform funerals, baptize, administer the sacrament of anointing, bless homes, and attend to the other needs of the faithful. This was done at night, and in the morning at 9 o'clock, wherever I was, I had to be at work. I slept on the bus or the train, depending on how I traveled home, and that had to suffice for my needs.

One could write about almost every village. Even a village like Zvyzhen, or Boryskivtsi on the Zbruch River itself, which once bordered the Russian frontier—even there I had to serve the faithful, because there was a need.

In addition, I was engaged in teaching young priests. I prepared about 30 priests for the priestly state at my own expense and with my own knowledge. It was not easy. There were some who had to be taught at my own expense, and I had to pay for their apartments and keep them with me. I was willing to do anything, as long as the Church had priests.

Just last year, 13 priests, 4 subdeacons, and 3 acolytes were ordained from my hand; all are working in parishes and all are satisfied, because it is my school.

For many years, I knew and was on very good terms with Kyr Pavlo Vasylyk. With him, there were other matters. He was often at my place in Lviv, twice a week. In my chapel, priests of the Eastern rite were ordained, converts from Judaism from Leningrad, Moscow, Vilnius. All this took place at my home, and afterward I would travel to help them with their studies and practical functions. This was all done with the blessing of the Apostolic See, through Poland, through the Dominican fathers. The work was serious and necessary, because one did not want to sit with folded hands. So that the works begun by the servant of God, Metropolitan Sheptytsky, would continue to develop, I had close ties with them, and thus the work was done for our Catholic Church.

For the 26th Party Congress, about 6,000 signatures from Catholics were sent to Moscow—I took charge of this—to grant us the legalization of our Greek Catholic Church.

The transfer of the relics of Bishop Josaphat Kotsylovsky, where I handed over the cassette and all other materials, also became the reason for my arrest, which took place on March 17, 1980, in Lviv, where I lived in my own house (now confiscated) at 36 Yanka Kupala Street, Apt. 3. During my underground activities, I devoted a lot of attention to youth and children; I wanted our rising generation and our children to have God in their hearts and to love their church.

On March 17, 1980, I was summoned to the Commissioner for Religious Affairs at 2 o'clock. I went, although I had ignored their invitations several times. Ilshchyn was not there; someone else received me and unceremoniously presented me with some declaration to sign, stating that I would not conduct underground services. I immediately refused and explained that, based on the constitution, I had the right to profess any faith and to celebrate services wherever I wanted, and I wrote as much. The partocrat did not argue one bit, calmly let me go. I was glad that the audience with the partocrat ended so quickly, because my mother was gravely ill, with her right side paralyzed, and they had called me to come home to Yablunivka without fail. I quickly bought a few things at the Halych Market, took a taxi, and by two-thirty I was at Yanka Kupala Street. I hadn't even had time to take off my coat in the summer kitchen when I saw 12 men cross the threshold of my yard. There were 5 families living in our house, and I didn't notice who these people were coming to see, but then I saw them coming up my stairs. After ringing the doorbell and getting no answer, because there was no one at home, the whole gang came to the summer kitchen. Demanding my documents, they presented me with a prosecutor's warrant for a search. This was nothing new to me, as my home had been searched 5 times already; it was like a habit. I went up to my room, because another priest, Roman Yesyp, was living with me. They also presented him with a prosecutor's warrant, and that hell began. From two-thirty in the afternoon until 7 o'clock in the morning, 12 men, and then more came from the KGB, and this inferno started. Everything began to be carried out of the house, all religious items, books, chasubles, cassocks, crosses; everything was destroyed and smashed. They carried things out until 7 in the morning, and in the morning, they put me and Roman Yesyp into a “voronok,” or “bobik” (paddy wagon), and took us to the prison on Myru Street. There I knew that all was lost, that I would never get out of there. There they took another 35 karbovantsi that I had in my pocket, my tie, my belt, and after drawing up another protocol, they threw me into a solitary cell, very small but very deep, where I sat for 10 days until I was transferred to the prison on Chapayeva Street.

On Myru Street, my first impressions were very frightening. A solitary small cell with wooden planks at a height of perhaps a meter, a small window with iron bars, and a faint light deep in the wall. And in the corner stood, forgive me for the first word I heard from some guard there, a “parasha” (slop bucket) for light needs, while for heavy needs they took you out several times at 6 o'clock in the morning. My nervous system was very agitated, and I wanted to go to the toilet every 5 minutes, but there was none, as they took you out once a day in the morning, down a long underground corridor, and in the cell there was just some small can.

The most frightening thing for me was when I remembered the stories I had been told by eyewitnesses of these Stalinist torture chambers. And I wanted to believe that in this very cell our best people had been brutally tortured, and that they were somewhere near me. It was impossible to sleep, because millions of thoughts gave me no peace, for everything was destroyed and many things had been taken, and not because I was sorry for them, I didn't think about that at all, but because I would have to answer for every scrap of paper. And in such a way as not to harm anyone in any way, but to take all the blame on myself.

I want to be truthful: the devil tormented me terribly: stick a finger in that light socket and it will all be over. But I quickly repelled this temptation. And the most frightening thing was the terribly large rats, which jumped on me like cats, and it was impossible to sleep for fear during those 11 days. I had nothing but a spring coat. They brought some food, but besides tea, I couldn't eat anything due to great anxiety, as my thoughts and reflections wouldn't let me swallow anything. On the fourth day, I was summoned to investigator Mykhailo Vasylovych Osmak. For particularly important cases—that was his title, and he drew up a protocol for me, or rather, read a prepared one, stating that I would be tried under Article 138 and some other three articles, but later they didn't charge me with them, I don't know for what reason. He told me that my investigation would probably be over in two months, but it dragged on for a whole 8 months, until October. On about the 8th or 9th day, they put a “plant” in my cell with me, some Jew who constantly talked to me about gold, money, where I hid it—in short, an unskilled agent. I didn't want to talk to him at all, and they took him away the very next day. Two nights later, they moved me to a general cell, where there were many criminal inmates. But what struck me most were the terrible curses, the obscene words, as well as several men with delirium tremens, who gave no peace day or night. On about the 12th day, I was summoned again and they took my fingerprints, or as they said there, “played the piano.” They drew up another protocol and in a “voronok” they transported me to the prison on Chapayevska Street.

As soon as I crossed the threshold, I heard: “Article?” “138,” was the reply. “Uniates, murderers, successors of Bandera and Sheptytsky, a nest of Slipyj.” And so on, such epithets accompanied me throughout my prison and camp life from these executioners of the people. The main thing was that I learned to be silent, although I have a direct character, but I immediately realized that you can't achieve anything by being aggressive; there, it was a short matter—a blow to the liver and kidneys. I saw many episodes of this in prison from the stupid and illiterate staff.

Then they took me to some solitary cabin. Then they took me again to some official, and again fingerprints and some records, which I don't remember exactly now. What I do remember is that in the corner near the chair there was a small mirror. And when I saw myself on the 12th day, I beg you to believe, I didn't recognize myself. A beard like an old man's, and for some reason all white, with a black hair here and there. While this official was writing something, I wanted to look at myself again. And indeed, it wasn't me; I didn't want to believe that it was me, that I had become like that, because by nature I like neatness and cleanliness. And then around 8 o'clock in the evening, they took me to the bathhouse. There were many prisoners there. They gave a piece of laundry soap the size of a finger and one razor blade for four men. The other three snatched the blade, and someone else took mine from my hands, somehow shaved, and then gave it to me. The water was almost cold, and the blade absolutely refused to shave my beard. I struggled, and time was short, about 10-15 minutes for the whole ceremony, so I asked one of the prisoners to help me, because they were mostly young men, and for some reason I didn't meet any like myself. True, someone took pity, probably because I introduced myself as a Catholic priest.

That was the worst, because it seemed to me that this dull blade was scraping the skin off me. The pain was incredible, blood flowed from the cut skin, it was very painful for me, but somehow I managed to shave. I had to wait a long time, until about 1 o'clock at night in some corridor, or rather it was some kind of “parasha” (toilet area), but no one was brought there. I was very hungry and cold, because it was some damp and cold basement. Around 1 o'clock at night, they moved me to cell 23, where a “plant” was sitting, I remember his last name exactly, Shtyr. He had been under investigation for a long time, about 2 years, and they moved him from one cell to another to find out something from the defendants.

I was very careful, because I knew a lot about such things from other competent people. I had a muskrat hat. I put it on the windowsill, but by morning it was gone. As I found out later, he sold it to a woman whom they call a "popkarka" in prisons, for half a liter of vodka and a piece of sausage. In the morning I asked where my hat was, and the answer was: “You'll say you forgot it in the bathhouse.” And so it was done. I was in cell 23 for about two weeks, I think, no more, because this Shtyr couldn't find out anything from me. And they took him out somewhere every day; he always said he was going for an investigation. But as it turned out later, they took such agents out to feed them and for them to give their reports. There was also a son of some general sitting with me, who had killed his mistress's husband and buried him somewhere in a field in Dubliany. He, in fact, confessed to this Shtyr, so everything was immediately revealed. They found the man in the field, hacked to death with an axe. I met him somehow in prison during a transport; he was given 25 years in prison.

Where I was held, it was a juvenile unit. These were terrible types, as an engineer from Dashava told me, but I don't remember his last name, because for some reason not everything stayed in my head. They transferred him, an old man, to the juvenile unit, but they didn't allow me, because I “corrupted” people like those who were there on the outside. Their conditions were better, they had better food, they drank milk, had a piece of white bread, not like our special-bake. One time there was a big commotion. They were given sprat for breakfast, so they covered the door with bread, turned on the tap, filled half the cell with water, sat on the second tier of the "koykas" (bunks), threw the sprat into the water, and had fun, until the "popkar" (guard) opened the door and all the water gushed into the corridor. It was a disaster.

Well, there were many such episodes with them, because they were lawless children and people without upbringing, culture, or control. On about the 15th day, they took me and put me in cell No. 71. It was there that the terrible things began, things that the human mind cannot comprehend or imagine. For all the days and months that I sat in that cell, it seemed to me that I was in hell. There one could see terrible scenes and hear enough for a whole eternity of everything that could be heard and seen. These were unprecedented people. I must note that not all of them were; there were four good and pitiable people, but there were also terrible beasts and inhuman monsters.

A little about that. The most terrifying thing in prison is the “propiska” (initiation rite). I want to say that this was not the invention of the godless authorities, who knew absolutely everything about all these lawless acts and terrorism, but remained silent and laughed. My good fortune was that a priest was not subject to the “propiska.” It was written so in their lawless code, but I had no right to interfere in anything. Before I came to the cell, there was a heavy iron door with two bolts and two locks. In the middle was a “peephole,” and at the bottom a “kormushka” (food hatch), which opened in the morning for breakfast, for lunch, and for dinner. The door opened if someone was being taken out or taken for interrogation or blackmail. When the door opened, truthfully, everyone was on edge: who, where, and why?

A little about the cells. Cell No. 71 held more than 70 people. It was long, with iron beds and terribly torn mattresses from long ago. The pillow was about 15 by 15 cm, made of matted cotton, also from long ago. One sheet and one blanket, also old and terribly dirty and smelly. No one ever washed it, because they only washed the sheets and pillowcases every 10 days. In the middle of the cell stood a table, lengthwise, chained and cemented to the floor, because the floor was concrete and terribly dirty. And it was so full of smoke that you could barely see anyone in the haze. I was the only one who didn't smoke, because I never smoked cigarettes. The cleaning, that is, the sweeping, was done by the "trubolioty" (parasites), those who were under investigation for “parasitism.” Their fate in prison was very difficult and unbearable. For some reason, they were terribly abused and beaten. That is, by the zeks, the "ringleaders," and there were 5 of them in the cell, mostly from the Mostyska Raion, and such scum that when I remember them now, I am ashamed that we all had to be afraid of them. Only they, the 5 of them, had the right to sit at the table, to eat there and play dominoes. Because there were dominoes in the prison, and they clattered them so loudly day and night that the sound probably still echoes in my head, in a word, with all their might. These "heroes" were also the judges in the cell. It's all incomprehensible when I ever recall this story.

The cell door opens. The “popkar” pushes you or another person through the door and immediately locks it with all the bolts. You stand at the threshold; the judges stop their clattering because there is a new victim. The cell interrogation and assignment begins.

The reader will probably not want to believe this. If I remember some things, I will recall them.

“Last name, article?” The mattress was brought with you. It lay on the dirty floor near the door. “About yourself.” “Article 138.” “And what is that?” “A Catholic priest.” “Oh, that’s something new. We haven’t had a priest yet.” A momentary softening and a consultation among the five. There was no lower bunk, only an upper one. They immediately threw someone out from below and allowed me to put my mattress on the lower part, because it's hard to climb up. They allowed me to spread it out and cover it with the blanket. The whole gang was around me. Hundreds of questions, because many were interested, as they had never seen such a thing. In Stalin's time, priests, bishops, and metropolitans sat with political prisoners, and that was their good fortune. There were cultured, restrained people, with respect and honor. They were allowed to pray. No one there used obscene words, out of respect for themselves and for that person. But here was a unique case: a priest and criminals.

Lawlessness. Well, such was my fate and my fortune. After questioning me exhaustively about everything that interested them, around 8 o'clock in the evening, they left me in peace. “You are not subject to the propiska, because you are a priest and you should and have the authority to judge others,” declared a little "shpynhalet" (pipsqueak) from Mostyska.

I would probably have strangled him if I met him now somewhere in life for these crimes and injustices that he did to these unfortunate people. Please do not be embittered by this word, but some people deserved such a verdict. They did not touch me, but said: “If it's not beneath you, you can sit and eat this slop at the table.” But as a sign of protest against the abuse of others, I refused and each time ate this slop and oatmeal on my bunk.

A little about the others. “Last name, article?” There were 4 options to choose from. I apologize that I must write everything as it was, because no one will ever understand this.

1. To eat sugar from the "parasha" (prison toilet)?

2. To eat soap and wash it down with water?

3. To fall from the top bunk, blindfolded, onto the cement floor?

4. To fight the "kamera" (cell) or the "kamerny" (cell leader)?

Please imagine, dear reader, which of these four options you would choose.

They didn't give much time to think; you had to have fun and satisfy their whims and passions.

Mostly everyone, and perhaps I too, if I had to be “initiated,” would have chosen the first and seemingly easiest option.

But eating sugar from the parasha looked like this... One of the ringleaders would defecate on the lid of the parasha, sprinkle sugar on top, and the unfortunate person who chose this option had to immediately eat it all. It was horrific. Anyone who resisted was beaten to death, and no one could complain to anyone. And if he knocked on the door and was taken out, then in a day or two the whole prison knew, because through an iron, aluminum mug they would signal through the wall to all the other cells that so-and-so was a traitor, and his fate was much worse than eating sugar with feces. As soon as such a person appeared and said his last name, everything was written down and the terrible abuse began. The “propiska” was done, he was allowed to put down his mattress, sit in a corner, not move, and not say anything.

2. Eating soap. To bite a piece of laundry soap with your teeth and wash it down with water. And afterward, terrible diarrhea, and no water to flush, because in Lviv, water was generally only available at night, and during the day, there was just a tank of drinking water.

3. The third option was the easiest, although it seemed the most terrifying. Such a victim was taken to the side, because the door was in the middle and the “popkar” could see the middle through the peephole, but no one saw what was happening on the sides. The "kings of the cell" used this to commit their lawless acts. And the third option, which seemed the most terrifying, looked like this. Such a victim was put on the second tier of the bed, their eyes were tightly blindfolded with a towel folded in four, their hands were tied behind their back, and they themselves took two blankets and 8 men held them, because if he jumped headfirst, he would be killed. He fell onto the blanket, and they laughed and had fun.

The 4th option—whether you would fight the "kamerny" or the "kamera"—looked like this. The "kamerny" was the hooligan ringleader who knew all the fighting techniques. If the victim said he would fight the "kamerny," he would start a fight with him, that is, he demanded that the victim hit him first, because he wanted to fight. And then a sad story would unfold from this. All beaten and bloody, even though the "popkars" saw it, they didn't know if he got it here or was beaten to death during interrogations. Everyone said that the investigator beat him, and no one ever checked these cases.

And when he wanted to fight the "kamera," an elephant's head was drawn on the wall with a pencil, and he had to beat the wall with his hands until they bled and with his head for hours, and if he didn't want to, they “persuaded” him in another way.

Regarding food. Everyone under investigation was allowed one package a month. Almost everyone received such a package if they had someone at home. But this package was not for the person it was intended for; the gang of five or six men ate it all. They ate butter, sausage, cheese, cookies, meat, well, whatever someone brought. The owners only signed for the receipt, and these hooligans ate it.

On Maundy Thursday, my sister also brought me a package, because a month had passed since my arrest. As she later told me, through the Basilian Sisters she found people whom I later saw, because they helped me in some things, and she paid so that she brought not a 5 kg package, but a whole 10 kg one, they could barely carry it, and it didn't fit through the “kormushka,” so they had to open the door. “Kavatsiv, sign for the package.” My heart leaped into my throat. I signed, but the package was no longer near me. The hooligans were already laying everything out on the table: sausage, ham, eggs, apples, butter, crackers, paska, well, everything my sister could put in. Because Easter was in three days, she wanted and thought that I would benefit from it all. It was clear that I knew I had to share, but there was no need to share; everything was already divided. I signed, sat on the bed, and read some book. The books there were some written-off ones that nobody needed, because they had no beginning, no middle, and no end, but so as not to be idle, I read something to make the time pass faster. In the evening, at 6 o'clock, when they brought a ladle of millet and a cup of hot water, one of these hooligans brought me two cakes to my bunk (I write bunk, because you can't call it a bed) and said with irony: “This is for you, batyushka (Father), for the package.” That was all I received from the 10 kg package. I remained silent. I didn't eat the cake, because a lump formed in my throat, and I gave it to a friend who was sitting with me and eating the millet porridge.

What is interesting is that there were over 70 of us, and these 6 hooligans managed to frighten everyone so much that everyone was silent, like a fish out of water. They scared all of us, saying that if we said even a word or complained, they would cut our throats like sheep during transport, and everyone was afraid of that. First time in prison, who knew how things were and what to expect. Fear overcame everything and everyone.

The worst was the terrible cursing and obscenity. No one wanted to speak in human language, but in a dialect of immorality.

A terrible picture was painted by the abuse of some individuals. These hooligans were always looking for victims not only for material gain for their stomachs but also to satisfy their passions. In a horrific way, they used innocent boys as homosexuals. They used them as they pleased, in various incredible ways, against their will. Two boys in our cell hanged themselves with a bedsheet, unable to withstand these terrible repressions and humiliations. One who slept above me hanged himself. They abused him terribly. I argued and shouted at them terribly, but the answer was always the same: “You, batyushka, don't stick your nose into this, this isn't a church, it's a prison, they don't touch you, so shut up.” Every day I had terrible scandals with them, but it was all unsuccessful.

For example. Such a bandit would undress completely, tie a towel around his head, drag such a victim onto his bed, use him as he pleased, and then after the act, give him a good beating, sit on him, and ride him like a horse for 2-3 hours. During this time, one person had to stand by the peephole, because from time to time the “popkar” would look through the peephole. By the time he opened the door, everything was in its place. When this victim could no longer crawl on the ground and fainted, they would lead him to the water trough to drink water from a basin where they spat and threw cigarette butts. After drinking the water, he had to continue being ridden. Or he would sit on his shoulders and be carried around for 1-2 hours at will. Of course, not everyone could withstand such repression and would take their own life by hanging. One of these ringleaders was on duty and wrote down who violated what. For example, when going for a walk for 5-10 minutes, because they didn't want to keep us longer, although by law it should have been an hour, upon returning to the unit, you had to be sure to wipe your feet, even if fictitiously, on a wet rag and wash two fingers in the washbasin. You couldn't go to the parasha for a bowel movement, because there was never water during the day, only after 12 o'clock at night, and so your body had to get used to managing itself that way. And for urination, only when there were 5 people. If there weren't, even if your bladder burst, you couldn't allow yourself to do it. Such a hooligan on duty watched everyone all day, and in the evening there was always a reckoning. These 6 hooligans would sit down after dinner and hold a kangaroo court. One would read the offenses and they would pass sentence. For not washing two fingers after urinating or for going to the toilet without a group of five, you were severely punished. Ten aluminum spoons were tied together with a towel and you were beaten on the soft spot as many times as sentenced, 25-30, and so on. After such torture, it was impossible to sit down, a fever would rise, but literally everyone was silent. Several times I said: “I'll call the block warden and we'll write a complaint.” But no one supported me out of fear, and I myself was also afraid, because there was still a lot ahead. A few times I was in the infirmary, but this was no longer happening there. My doctor was some Maria Vasylivna, a major. A very kind and compassionate woman. And the head was also very good, because he knew a lot about me, about my activities, and I had performed a funeral for someone in his family or among his acquaintances, so he treated me cordially, but it was impossible to stay there for long, because there were their own norms. The administration knew absolutely everything about these kangaroo courts, but they all remained silent, because they were interested in seeing the defendants abused like that.

During the investigation, I raised this issue of lawlessness many times before Osmak, but it was all to no avail. It was very convenient for them in this lawless society to conduct such experiments, because they themselves were no better, they also tortured and abused people as much as they wanted, damaging people's kidneys and livers.

As for the investigation, I was interrogated about 120 times. The interrogations were tedious and pointless, the same thing over and over. Osmak traveled to many villages and cities where I had served and questioned everyone, and then he would twist my head for hours. Osmak tried to confuse me in the investigation, but I never signed a protocol for him if he changed something and it wasn't as I had said. He had to rewrite the protocols, and so he was terribly angry with me. They had a lot of time, a full 8 months. There was time to travel and time to twist my head. There were two investigators. For some reason, I don't remember the second one's last name. What saved me was that I was on good terms with Father Protohegumen Pakhomiy, and since he was already in eternity, I allowed myself to attribute everything to him. That they were his notes, that I had taken everything from him and hadn't looked through it myself, that I didn't know what it was for. There were also confrontations with many people. In a word, a whole 6 volumes were compiled from the investigations. And the seventh and eighth volumes were from the trial, which lasted from October 14 to October 28, where every day photo cameras, television cameras, journalists, and correspondents from all the newspapers worked, because they were trying a great criminal who taught people to love God and taught religion to children.

As Tetyana Protsyk told me, who remained in my house after my arrest and took care of everything until the final verdict, Osmak, from the golden chalice that he took from my house, where the Divine Liturgy, the bloodless sacrifice, was celebrated, made himself an ashtray in his office, in front of her eyes, put his feet up on the table, and smoked, flicking the ash and cigarette butts into the consecrated chalice. And now he is the prosecutor of the city of Lviv, a guardian of order. What a terrible injustice! It is precisely for the harm done to others and for the labor of others that the partocratic system gives such high positions to those who should be tried for the crimes they committed.

There was a lot in the investigation, but that's a whole other story, because it's a terribly monotonous and meaningless conversation. Whatever I said, he would twist it his own way. He went to villages and schools and dictated to the children what was convenient for him, to increase the measure of punishment. Children from the 5th to 10th grades wrote that I forbade them to eat meat, watch television, and dance. All of this was completely baseless. As for fasting, I taught as the Second Vatican Council proclaimed. The first day of Great Lent and Good Friday without meat and milk. Every Friday without meat. Children under 12 are not obliged to fast. As for dancing, I have no right to forbid what they dance at school, but that minors should not go to clubs during Lent is realistic, because no good mother would allow her child to wander around clubs in the evenings. As for the television, I had a television and watched it when I had time, and in general our broadcasts are not immoral, so there were no reservations on my part. Everything was invented and fabricated, because Article 209 provides for confiscation, exile, and a term of 5 years.

The trial was terribly shameful. The witnesses said that they wrote under dictation, but no one took this into account. They disgraced themselves by asking students from the 8th to 10th grades if they were Komsomol members. They said yes. “And how can you, a Komsomol member, believe in God?” “They forced me to join the Komsomol, but I believed in God and still believe.” Many were expelled from the Komsomol at the trial as useless.

The witnesses also included priests of the Russian Orthodox Church, such as Udych, the parish priest of the village of Zavadiv-Holobutiv, Ilyeshsky, the parish priest of the village of Trukhaniv, and the parish priest of the village of Zhovtianci in the Kamianka-Buzka Raion. In their denunciations to the KGB, they wrote that I spoke out against the Soviet government, conducted agitation, and the like.

For example, the priest of the Russian Orthodox Church, Udych, wanted to say before the people that he did not know me and had never seen me, and that what was written there, the investigator wrote himself, and he signed it without reading. With the permission of prosecutor Dorosh, the judge read out the entire confession that Udych had written at the KGB. It was something terrible and outrageous among the population. I did not see this, because I was in the hall, and the trial took place in the Builders' Club on Stefanyka Street, one of the largest clubs in Lviv, but only those people who taught Marxism-Leninism and trusted party members were allowed in with special passes. In addition, my sister Olha, Nusia, Tetyana Protsyk, and a few other people were always there—with the permission of the investigator and the prosecutor, with passes. And the witnesses were not allowed to go outside, so they were forced to sit in the courtroom that day. It was a shameful trial for Soviet society. All the people were behind me, but the dark reaction did its work and succeeded. The trial was torture. Every morning I had to gather all my things and carry everything, including the mattress, to the storage room. And late in the evening, they would bring me back to the prison in a “voronok.” 8-10 men with dogs guarded me. The people, who stood by the thousands outside the court, lay down on the road under the vehicle; everyone wanted to see me, and when the vehicle approached, there was such a cry that your ears would ring. I couldn't see anything, because the “box” was dark. They brought me in through side doors.

I had to quickly jump out of the voronok, and under bayonets, they led me through side roads, and always different ones, to the courtroom. The people shouted and demanded justice, but it was all in vain. The party system worked its own way: “Sasha, get them.” The witnesses at the trial were KGB chiefs, heads of the militsiya, district officers, heads of raion executive committees, secretaries of raion committees from many raions where I had worked. I want to emphasize that for some reason these people did not want to testify much against me. Compared to others, they gave their testimony quite objectively and said what they knew, that I celebrated services, that they had been to my services many times, but they had never heard me speak out against the Soviet government. On the other hand, people like the head of the village council of Mshana, the head of the village council of Hradivka, of the villages of Zavadiv and Holobutiv—these partocrats tried with all their might to show how honestly they serve the party and what atheists they are. God has already punished two people from Hradivka and Mshana; one from Mshana died in terrible agony and asked

for forgiveness for her crimes, and the other from Hradivka, when her son was brought back from Afghanistan in a zinc coffin, went insane and screamed at the top of her lungs that God had punished her, and that she spat on the party. The hand of God's justice still hangs over the others.

I never asked God for revenge, but God is just; He repays everyone according to their deeds.

Although the trial was shameful, it ended as the KGB and those functionaries wanted for me: 8 years of imprisonment and confiscation of all property.

On the day of my arrest, almost everything was taken away, and the rest was inventoried, and Tetyana Protsyk took responsibility for it, but after the trial, 10 days later, everything was confiscated—the house, and the tomb where the remains of Bishop Kotsylovsky lay.

I was transferred from cell 71 to the transport cell 117. It was a little easier there because people changed every day, some were taken to the zone, and others were brought in, but there was no lawlessness like before the trial. I filed an appeal, and only on December 15 did the Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR consider my complaint. Everything remained unchanged, except that the collegium changed the ruling that my actions were not for personal gain, as the regional trial had decided, but for purely religious motives. I waited for the transport. During this time, the mendacious Soviet press wrote what they could, showed and highlighted it on television, spoke on the radio, about what a bandit and saboteur, a follower of Sheptytsky and Slipyj, Stepan Bandera and Stetsko, had been convicted. The people reacted differently. Those who knew me, for whom I had worked, endured all this with sympathy and a heavy heart, while the enemies triumphed and rejoiced.

On December 13 of that year, my father died. The cause of death was precisely this, that the day before his death he saw the trial on television and said: “Now I can die, because I will not see him again.” I learned about my father's death a little later through good people who worked there.

On January 7, on Christmas Day itself, my sister again, for money, through good people, arranged a package for me. I benefited little from this package, because what she sent could not be taken into the cell. They called me into a quiet little box, and what I could eat was mine, and the rest that was possible was passed to me in cell 146, and they informed me that on Saint Joseph's day, at dawn, I would be taken from the prison.

My sister and other people collected large sums of money and paid these liars who said they would buy me out, but the money was lost, and I had to stay in prison.

Early on January 8, I was put in a “voronok” and taken I don't know where, because I was again in a “box,” with dogs. They put me on a train. The train was terribly overcrowded. There were masses of people. The car consisted of compartments where prisoners of different regimes sat.

In the compartment where I was traveling, there were very many prisoners. About 40 people sat in one coupe; there was no room to breathe. Two or maybe three soldiers, mostly “churkas” (a derogatory term for Central Asians), walked along the length of the car and always answered "nelzya" (not allowed), "ne polozheno" (not permitted).

A transport is a terrible word, and terribly endured in the Soviet way.

For the transport in Lviv, each of us was given a bundle of thick cardboard with rotten sprat and a loaf of bread. That was all for the transport. Where they were taking us, I don't know, because no one cared about anyone. The train sped towards Kharkiv to a transit point. A stop. Night. The terrible barking of dogs and many soldiers; about 50 of us were thrown off and led by dogs, but at a very fast pace, to a “voronok.” They packed us into the “voronok” like herrings and drove off, for quite a long time. I later learned that this was Poltava, and in the new prison, they threw us out like hawks at a fast pace, until we found ourselves in the Poltava prison. New curses and profanities from the staff: “Hooligans, bandits, murderers, we'll shoot you like crows!” And so on...

A new "processing." Take everything off. All things, everything into the furnace, because lice were swarming on each of us. We had to wait quite a long time until everything with the lice was steamed. But in fact, it only warmed up and helped the lice see their victim sooner.

But they let us shave and wash a little, even with cold water, because for some reason there was no hot water then. I think the stoker was drunk and didn't fire up the boiler. They issued wet clothes, everyone found their own. The mattress, as in all prisons, was old and damaged. We were distributed to cells. Again, a terribly large cell and a multitude of people, because it was a transport cell. The windows were boarded up tight. It was so smoky it was black, and cold, because it was winter, January. The food was much worse than in Lviv, because in Lviv the special-bake bread was a little better baked, but there, in Poltava, you could make figures out of the raw bread. But to hell with it. What I remember is that it was terribly inconvenient there; the spoons had very short handles. As I found out, they were from a poultry farm, where an egg was placed to incubate a chick. The spoon was very deep and cut your mouth. Everyone had sores at the corners of their mouths. Slop, as usual, and oatmeal, and in the evening a ladle of millet, and undercooked at that, which was the case in all prisons and camps. Food was given through food hatches, like to dogs. In the cell, there was always a duty crew of several people who received the food, distributed it, collected the dishes, and washed the floor. They didn't notice me there, because they were far from active. But there were no more quarrels. Everyone sat in their place, that is, on their mattress, because there were no beds, it was a solid platform welded from thick sheet metal, everyone lay side by side like herrings and waited for their new transport. No one knew where anyone was going. All the documents were somewhere in the special section. I was in Poltava for about a month and a half, and it seemed like an eternity, because every day was like a marketplace: dozens were taken out, and others were brought in. Many slept on the floor because there was no room on the iron platform.

The time came for my turn. “Sobiraysya!” (Get ready!). I gathered all my things, or rather a sack, because everything had to be handed over to the warehouse. We had to wait a long time, almost until night, for the transport. Everyone was in some large cell with toilets, in a terrible noise. And in fact, they took us to some train only at 8 or 9 o'clock in the evening. They quickly loaded us into a “dushehubka” (gas van)—a “voronok”—but so many of us that it terrifies me even now when I remember it, because we waited a long time near the station, and the long-distance train was delayed for about 2 hours. Our bones were cracking. There was no room to move anywhere. There was nothing to breathe. I was preparing for death there, because indeed, a person with a heart condition and hypertension could not have endured that transport in such a state. It is a terrible thing, comparable to death. Only someone who has endured transports can know this. This train was a bit freer, there were fewer people. After some time, and it was 5 o'clock in the morning, the train stopped. Six of us were taken off the train and led to a “voronok.” We were guarded by 8 soldiers with muzzled dogs. No one spoke to anyone. This was Romny, and we had to travel to Perekhrestivka, to camp 319/7.

The road was like a cradle; you didn't know what to hold on to. We all rode in silence. A signal. A wide camp gate opened on both sides, and we were led inside the zone. The gate closed automatically, and the 6 of us were taken to some basement room, “for processing.” They shaved our heads again, even though there was nothing to shave, but that was the law. They washed us, changed us into all camp clothes. They did a full search of what I had. Everything I had, except for my boots, was taken, recorded in a report, and put in a sack. They gave me an old uniform for 12.50, a padded jacket, and a hat—and that was all my property. I had two notebooks and a few envelopes. In 4-5 hours, three men from the operations department came and began a conversation about the camp way of life. That we are completely rightless people, cannot demand or ask for anything, because we are deprived of our freedom and all the rights that people in the world have. We are criminals. Well, such agitation was very tedious and useless, because we already knew everything, that we were slaves and without rights. First of all, I had to write a statement that I refuse to drink tea, because this was zone 319/7, a no-tea zone. If anyone was found with tea, they would be severely punished. Without any resistance, I wrote such a statement to get rid of them, because everyone was writing one. The men who shaved me said it was useless to argue, because you won't find justice anywhere. Around 2 o'clock, or maybe 3, when everyone had probably eaten, they took us to the dining hall, gave us food and warm water. I felt better. Back to the basement, to wait for the evening distribution. And during that time, around 6 o'clock, they took us to the infirmary, took samples, did an X-ray, and all other procedures, weighed, measured, etc.

The distribution was like this. In the colony chief's office sat all the detachment chiefs, the head of the regime, the KGB, the operations group, and all other functionaries. We entered one by one. The transports were from different trains, so there were many of us.

Take off your hat, bow low, state your last name, first name, patronymic, article, year of birth, etc. Before the colony chief lay the "Delo" (file). He carefully, as I noticed, turned the pages one by one, glancing at me from time to time. His last name was Kyrylenko. He looked like an intelligent and pleasant gray-haired man, who made a pleasant impression on me.

“What were you convicted for, what did you do?” “I celebrated Divine Liturgy and taught children and people as a Greek Catholic priest.” “You don't want to sign up for the Orthodox Church?” “No! I am a Greek Catholic.” “Do you know that we have the right: you could be free today if you just sign once that you agree to serve the Orthodox Church.” “No! Citizen chief, I do not change my faith. If I must die, then let it be today.” “You will regret that all is lost.” I laughed ironically and showed with my decisive gesture that this was not a conversation for me. “Well! You have the right.” Of course, a long and tedious conversation began, because everyone wanted to ask something, as the camp chief said: “We have had everyone here, but we have never had a Catholic priest, this is the first time.” Kyrylenko, with whom I had 6 conversations during my time in the camp, was not a bad man. Firstly, I never heard him swear. He was the only man in the camp among the authorities who didn't. Everyone asked something, and there were still many people, that is, zeks, but no one was in a hurry there, because there was time, and a lot of it. Assignment: “7th detachment, 72nd brigade. This is a blessing for you, as a priest.”

The 72nd brigade was a privileged brigade, that is, for people with higher education, mostly they were work controllers. The job was supposedly easy, but responsible, because there could be no defects, and the controller was responsible for defects. In the evening, around 11 o'clock, they took me to the barrack. It was large and long, with 4 rows and three tiers, plus extra "bayans" (makeshift bunks). About 750 men. They assigned me the second tier, the duty officer wrote me down in the books, showed me to the brigadier. For two days, they didn't take me out to work. They had me wash the walls in the barrack, in the corridors, with soap, until they shone. It was very cold in the corridors and rooms. Wash and wash. For two days, my head was spinning. There were two of us in this transport who ended up in the 7th detachment. We washed, scrubbed, did everything they said.

When I was brought to the camp, it was a Friday. On Saturday and Sunday, I did this work. In the evening, quite late, at 9 o'clock, I was called to the infirmary. I was, in fact, feeling very bad, but I couldn't ask anyone for anything, because I didn't know anything yet. I found several prisoners there, because the head of the infirmary himself, Yarotskyi Yosyp, a Jew, was on duty. A nice and cordial man. My turn came. He had my medical history in front of him, which had come with the documents in the "Delo," and he says: “Article?” “138, 209.” “And what is that?” “A Catholic priest.” He became very interested, started a long, heartfelt conversation with me, but when he measured my blood pressure, he was frightened: “How can you work when your blood pressure is so high, 265/165?” For some reason, I hadn't noticed, because I was terribly stressed from the transports, the fears, the overloads, etc. He says to me: “I am keeping you in the infirmary, you cannot work, because you could have a stroke or a heart attack. I don't want to be responsible for you.” He put me in the infirmary, and I lay there for 5 weeks, maybe more. They brought my pressure down to 220/140, but they couldn't keep me in the infirmary any longer, so they discharged me for work.

I went out to the barrack, but my job had been taken by others. Around 4 o'clock, they took me to the second floor to the rate-setter. Since my specialty is accounting, they assigned me to calculate the wages for the convicts. Well, for me, this was something great. There were only two of us in the room, because in the next room sat the workers of the technical department, quite cultured and polite people in uniform and without. My duty was to wash three large rooms every day, sweep, bring water in carafes for drinking, water the plants, because there were flowers there, and the entire payroll of the zone was my responsibility.

The rate-setter was a drunkard and rarely sat in his office. He always came late and left the zone early. The entire burden was on me, but I managed. It didn't last long, because the colony chief, Kyrylenko, called me in and said that there was an order from the KGB to transfer me only to hard labor. I had to say goodbye, and only when there was a failure, when they demanded wages outside the zone, they would secretly lock me up and I would calculate the wages, because no one else knew how. Before me, there was some Dekhteriv, I still met him, he had served 10 years for machinations, did this job, but when he was released, there was no one to do it. The shuffling from place to place began, and what and where I didn't have to do. It seems there was no job I didn't do, even though my blood pressure was very high and my heart ached. No one paid any attention to that.

A little about camp life. Almost 750 men lived in the barrack. In the summer, it was terribly hot, because all the windows were boarded up tight and not a single casement could be opened, and in the winter, it was terribly cold, frost would build up all the way to the bed, and my bed was under the window. In the summer, it was a little better, because there was at least a gram of fresh air, and in the winter, I wrapped my head in a towel. The most terrible thing was that the convicts swore and cursed so terribly. It was truly hell, but without fire. It was a terrible horror. It was impossible to listen to it all, but you can't cover your ears. They fought among themselves, had various showdowns, and this happened every single day. It seemed that it would never end. And I had a mountain of days ahead of me. There was almost no one to talk to, because it was mostly young people, and they were little interested in such matters, or almost not at all. I communicated with a KGB colonel from Kyiv. He was serving time for bribery and received 5 years. He was an exceptionally intelligent, sensitive, and kind person, his last name was Klymenko. His mother had once worked in the Central Committee but was a pensioner; she found a way and bought him out after 2.5 years. We often talked, and on all topics; I was cautious, but we were sincere, I knew he would not betray me, because he hated the Soviet authorities. They often reprimanded him to stop communicating with me, but they did not succeed. “What, does he want to make you a Uniate?” they asked him. They took him out of the zone when I was at work. He often wrote to me and informed me of some things. He came to my home, and I was often at his home, celebrating the Divine Liturgy. He lived on Gorky Street.

Wake-up was at 5 o'clock, because you had to wash and get ready before the zeks got up, because at 6 o'clock everyone had to be at morning exercises, whether it was winter or summer, rain or bad weather. I got up beforehand, because later everyone would defecate and shout like wolves, and such a small "kaptyorka" (they called it a drying room, although it was always cold there, because they never heated it, neither in summer nor in winter). In such a small room, there were several posts with hooks on which they hung padded jackets. On one such hook, 15-20 jackets were hung; to get the one at the very bottom, you had to pull it out, and all 15-19 would fall to the ground, you would take yours, and the others would be trampled underfoot. It was a terrible horror, because you couldn't be late for exercises for a minute, well not a minute, but for 2-3 seconds, because warrant officers stood there, took you to the checkpoint, and immediately drew up documents to deprive you of either your store privileges, or a package, or a visit. For this reason, I slept like a sparrow, and at 5 o'clock I got up every day, through all the times, and washed, got ready, and then sat quietly on my bunk, watching with one eye to see if a warrant officer was coming, because you couldn't sit on the bunk, that was also recorded as a violation, and with the other eye, I dozed, so that when the anthem of Ukraine, "In the Soviet Union you found happiness," played, it turned my stomach with such happiness. For prayer, for teaching children to pray, I sat like a prisoner and had to suffer for years with hooligans and criminals. At this anthem, I would go out to the “lokalka” (local zone), and when the chimes on the Kremlin struck, everyone had to be standing on the square, waving their arms, jumping, doing various exercises for 15 minutes, and then they would go into the barrack, gather in the “lokalka,” and go out in single file by brigade. And there were many brigades in our barrack. In groups of 5, we approached the warrant officer, who recorded the number of people, checked with the brigadier, and let us into the dining hall. It was a terrible discipline. They did everything and experimented on us, because our zone was being converted for particularly dangerous recidivists. Every day in that system, they counted all of us 18 times a day. Some times you had to say your full name, last name, first name, patronymic, article, term of imprisonment, beginning and end of the term. You had to know this prayer, day and night. And other times they just counted us like hornless cattle. In the evening every day, and on Sunday during the day at 9 o'clock, everyone without exception, except for those lying in the infirmary (and there was room for 15 people, and if in the corridors, then 25), was taken out to the "plats" (parade ground) and counted by brigade, by group, and because the warrant officers were always either drunk, or to be honest, illiterate, they were always missing someone, either 2 were missing, or 3 were missing, or there were too many, and they ran around the square like jackals and couldn't balance the count. This terribly irritated all of us. In winter, terrible cold, rain, snow, frost, and in summer the sun baked, and in bad weather they threw a rain cape on themselves, and in summer they wore short sleeves, and thus demoralized people. At the same time, we also had military training. In case of war, all of us would be sent to the front line for the Motherland. We all laughed terribly at this and were indignant; everyone said that the first bullet would be for these illiterate warrant officers who caused so much harm, even to those criminals.

Some of the staff treated me correctly, using the formal “Vy,” but there were many scoundrels who really considered me a criminal; the fact that you are a priest and a Uniate on top of that was like being a "hairy devil" with horns. During such exercises, it was “Leg higher, hands to your chin, wider step,” etc. This terribly irritated me, because I am not liable for military service and am removed from the military register, but I had no rights and no one had any rights over me, but where can you find rights in a lawless state, and in a camp at that. My God! It seemed that there would never be an end.