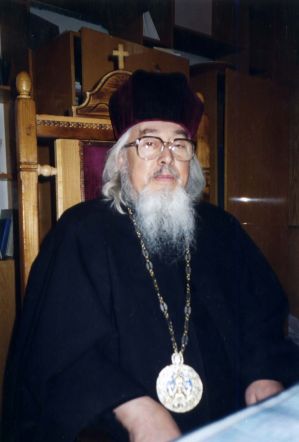

Memoirs of the Bishop-Ordinary of the Kolomyia-Chernivtsi Eparchy, His Grace PAVLO VASYLYK.

Recorded by Yu. M., 1991–1999.

Scanned, proofread, and posted on the KHPG website on the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord, February 15, 2008, by V. Ovsiienko.

Published in: The Christian Herald. Journal of the Kolomyia-Chernivtsi Eparchy of the UGCC. May 1999, issue 7 (67), special edition. 24 pp.

The life of the unwavering Warrior of Christ, the Most Reverend Bishop, His Grace Pavlo Vasylyk, is an example of service to our Church and Ukraine. We are recording the memoirs of his thorny path through life. We want to publish a book.

The work on these memoirs is not yet finished. We are publishing them as they are, not only to commemorate the Bishop’s Jubilee, but also to receive help from our Faithful.

Among you, Dear Brothers and Sisters, are those who shared prison bread with the Bishop and suffered with him in the Stalinist and Khrushchev-era concentration camps, who were present at his underground services, who keep the letters and photographs he wrote from behind the barbed wire.

We kindly ask you to bring us these rare and important documents. We will return them after copying. They will be used in the book.

We ask for clarifications and additions.

We hope for your understanding and support.

The Publishers.

1.

The closer a man gets to his earthly end, the more often he recalls the time and place where he came into God’s world. With great joy, he revisits the paths of his childhood.

I, too, was there, where I took my first steps. But I did not feel joy from my visit, but great sorrow. For the paths of my childhood have become overgrown. Not just with grass and weeds, but with trees and bushes. A forest now murmurs on the site of my village. Although the trees grow thickest where the church and cemetery stood, a few tilted crosses still remain here and there in the old graveyard. And one cross, with an iron Crucifixion, showed me where my school had been.

I recognized that cross. I remember it for as long as I can remember myself. It stood in front of the school, and it stands on that spot still, only it’s no longer planted in the ground but propped against a tree, for it has rotted through.

That this was the same cross, and that the school had been there, was confirmed by a man from our village who had hidden from the Poles when we were being deported and had remained to live here. He told us that immediately after our departure, the Poles set the village on fire. They did not dare to burn the church. Several years later, they dismantled it, using the wood for their own needs.

They destroyed the village and planted a forest to erase its memory. But the heart preserves the memory, though it bleeds. It was my heart's pain, not that of my hands or face, that I felt as I pushed my way through nettles and thorns to my father’s doorstep. The foundation of our house had not yet sunk into the green vortex.

Among the trees, I recognized our apple trees and the pear tree that I loved so much. It already stood withered, choked by thistles.

The last time I was in my village was five years ago. At that time, our fellow villagers who had managed to remain on their native land gathered on the wasteland from the surrounding villages. I celebrated the Divine Liturgy on the ruins so dear to us. We erected a strong oaken cross near the church.

I do not preserve my native village in my memory as I saw it at our last meeting. It was picturesque. The fields were on the hills, and the village nestled in a small valley, as if in God’s palm. It was surrounded by forests, and what once roamed in those woods is evident from their names. One of our forests was called Turnytsia. I did not find any aurochs there, of course, but when we went there for raspberries, we could startle a hare or a fox. From behind the distant trees, handsome stags with large, magnificent antlers would gaze at us and roar so loudly it was frightening to hear. In the thicket, one could encounter a wild boar or even a bear.

There were forests around our village. Forests, pinewoods. Glorious pinewoods. That is why the village was called Boryslavka. Twenty-four kilometers from Przemyśl, on the ethnographic border between the Boykos and Lemkos. I don’t even know for sure which I am: a Boyko or a Lemko. When someone asks, I say: if I need to be a Lemko, I am a Lemko; if I need to be a Boyko, I am a Boyko. But I always want to be a Ukrainian.

It seems to me that it was not only my upbringing at home, or certain teachers at school who, at the risk of losing their positions received from the hands of the Polish chauvinistic administration, told us who we were, nor was it just the songs of the youth on warm summer evenings, but also the small stream that flowed not far from our house that made me a Ukrainian.

In good weather, you had to listen carefully to hear the silvery chime of its crystal-clear ripples over the rainbow-colored stone bed. This wondrous music was heard not only by us children, but also by the fish that swam in the stream, lazily wagging their tails. And even pstruh (trout) would swim to us from the mountains, for Boryslavka is a submontane village.

Our stream played a different instrument when there were rains and downpours. Then it would swell, turn black with rage, and roar like the Dnipro. But even then, we were not afraid of it. The banks were high, and our grumbler could not bring misfortune to the village.

It was the Poles who brought misfortune to Boryslavka.

It is natural that a man departs, having first accompanied his relatives on their final journey. In departing, he also leaves behind the footprints of his childhood.

The footprints of my childhood have been destroyed. This pains me greatly, which is why I began my memoirs not as everyone does, not with a story about my relatives. But now that I have poured out my pain and thus soothed it a little, I will continue my story in the usual order.

So, I was born on August 8, 1926, in the village of Boryslavka, which belonged to the Przemyśl county of the Lviv voivodeship. I am the son and grandson of Sich Riflemen, for both my father and my grandfather were in the USS. My grandfather was even wounded at the front, but my father, thank God, came back whole.

My father’s name was Yakym, son of Mykhailo. A hardworking, respected farmer, he was not very talkative by nature. He did not like to talk about himself, so I know very little about his time as a rifleman. I only know that he fought in Volhynia. Sometimes he would mention the town of Sarny.

My father was not only a good farmer, but also skilled in carpentry. He had the soul of an artist from God—he played the violin and the accordion well. He was self-taught. His life turned out in such a way that he could not develop his abilities with proper training, but they were very useful to him in his interactions with people, and most of all, in raising his children.

My mother was Ksenia, née Kulhavets. No family trees were kept on either my father’s or my mother’s side, but a legend has been preserved that my mother came from a Cossack family. They say that in 1775, someone from the Zaporozhian Sich, which had been dispersed by Catherine, limped all the way to our lands and put down roots. Perhaps it is just a legend, but my mother had a passion unlike that of our women and girls: she loved to ride horses. Sidesaddle.

My mother also differed from others in that she was perhaps the best gardener in the village. Large red tomatoes, which were still very uncommon, ripened in our garden. Both they and new varieties of vegetables spread throughout the village from our house. To this day, it seems to me that no one grows beans, potatoes, beets, carrots, or cabbage as beautifully as my mother once did.

And then there were the flowers. My mother took great care of them. There were flowers in the garden, in front of the house. The cattle shed, the house, and the barn were under shingle roofs, the haystack covered with straw; a wattle fence and—flowers, flowers, flowers... Lord, how could a hand be raised against such beauty! To turn an earthly fairytale into a wasteland!

The garden was under my mother’s care, the orchard and the field under my father’s. Father grafted pear and apple trees. We even had plum trees growing on the boundary strip in the field. On those Hungarian plum trees, we children learned to count; there were over a hundred of them.

We had about ten hectares of land. We sowed spring and winter grain. There was enough for ourselves and for sale. There were always two cows and two calves in the cattle shed. We kept chickens, geese, and pigs. There was enough to feed the children.

And there were eleven of us, my father and mother’s children. Nine are still alive today.

I wanted to write about each one separately. But the storms of life that ravaged our twentieth century have added so many facts (mostly unhappy ones) to our biographies, to each of us of the older generation, that to describe everything would fill a book for each person. I encourage everyone to write such books. They will be the best textbooks on our history for future generations.

About my family, I will say only one thing. None of Ksenia and Yakym Vasylyk’s children went down the wrong path. Not one of them compromised their soul to get a cozier spot in life; not one of them joined that misanthropic party, even though, having a higher education, they were thereby ruining their careers. What all the Vasylyks had enough of on their life’s journey was thorns. I was the only one who became a servant of the Lord.

My father, a Sich Rifleman, made sure that we grew up nationally conscious. As for religious upbringing, it was inseparable from the national. It was a single whole, for our national traditions had long since merged with the spiritual, the Christian.

We all went to church. To festive services—from the earliest age. When we could not yet walk, we were in the arms of our father, mother, or one of our older brothers and sisters. Each of us, upon learning to read, received a little prayer book as a gift. We went to church with our prayer books. In church, we prayed, sang, and listened attentively to the sermons.

At home, besides the constantly subscribed “Dzvinochok” and the little books by Andriy Tchaikovsky, we also had religious booklets. We regularly received “The Missionary.” It and “The Lives of the Saints” were read to us at home. My father and mother, although very busy with us and the farm, found time to serve the church. Father was in the church Brotherhood, and mother in the Apostleship of Prayer.

Every year in August, when the Assumption of the Mother of God was celebrated according to the Roman Catholic calendar, we would all walk to Kalwaria. It was seven kilometers from us. The Ukrainians had their own indulgence, their own Way of the Cross, and a beautiful church there. The Poles later razed that church to the ground...

I started school in 1933. At that time, there was a famine in Greater Ukraine. In the village, at the “Prosvita” reading room, and in the church, there was much talk about that famine. “The Missionary” had photographs of children starved to skeletons. The village sent food to the starving, but the Soviets did not let it cross the Zbruch River.

I remember my teachers only by their last name: Woźni, a married couple. They were staunch Ukrainians. The Poles persecuted such people, but they bravely did their work—they raised us to be Ukrainian patriots.

We were much more obedient then than children are today, and so we benefited greatly from our studies. During breaks and after school, we played Cossacks and Sich Riflemen. Everyone was armed. We carved rifles and sabers from wood, and popguns from elderberry branches. And our bows could actually be shot. The arrows had metal tips.

I also “fought” with the others, but I was more eager to make myself a cassock from some piece of clothing and an epitrachelion from a towel, and imitate our parish priest. Once we even buried a pigeon that a cat had killed, with singing and sermons.

But those were still the unconscious games of childhood.

I felt that I wanted to be a priest when I was in the third grade. It happened after an incident that deeply upset me. At that time, the parish priest and our catechist was a young priest, Fr. Pavlo Pavlish, because when I was at the beginning of the second grade, our Fr. Mykola Shchepansky, who had baptized me, was transferred to another place by His Grace, Bishop Yosafat Kotsylovsky.

One Sunday, Father Pavlo stood in the Royal Doors and said:

“People, tell your children to watch the cattle when they drive them to and from the pasture. Because they are not watching them, and your cows are trampling my crops and causing me damage.”

I knew what had happened. A person’s cow had caused damage, but not through the negligence of the shepherds, but because of the heat. The heat, the swelter, the cows ran off. Who could catch them... And since the church field was not fenced, how were the shepherds to blame?

And even if they were to blame, could such things be said in church? I thought to myself that I would never say such a thing in church. And I would ask God to help me become a priest. And I would not need a church field. I would give it away to the poor.

I finished four grades in my home village. Then I went for two years to the neighboring town of Rybotychi. In our Boryslavka, there were only Ukrainians, but there were many Poles there. They had their own church.

We often fought with the Poles at school. The Polish teachers tried to Polonize us, but we resisted. We had tremendous support from our catechist, Fr. Haidukevych.

After the sixth grade, my father took me to the gymnasium in Przemyśl. The classes in Rybotychi were at the gymnasium level, so in Przemyśl, after the corresponding exams, I was admitted directly to the third grade.

From Przemyśl to Boryslavka, it was 24 kilometers by road, and 14 through the mountains. My family visited me rarely. I missed Boryslavka very much. In the city, there were beautiful churches and a Theological Seminary, where I hoped, with God’s help, to realize my dreams.

I was an unusual gymnasium student. Mischief, games, and excessive jokes were not for me. I read a lot. Not only what was required by the gymnasium curriculum, but also spiritual literature. Here I had greater access to books. I often went to church, to confession, and to Holy Communion.

I lived like an ascetic. I fasted strictly. I mortified myself, flagellated myself. In a youthful, fanatical fervor, I would let my own blood. To this day, I have scars in the shape of a cross on my wrist. I made my body suffer, tempered my soul.

The Przemyśl Cathedral became like a second home to me. And when we, the gymnasium students, marched in formation to our cathedral every Sunday and on holidays for the “nine o’clock,” for the service celebrated by His Grace Bishop Hryhoriy Lakota or other canons, it seemed to me that we were going to my home.

But the first Soviets came, and we could no longer march to church in formation. The first time, they did not yet dare to close it, and no one could forbid me from going to it as often as I wanted.

The first Soviets did their harm secretly. In some village, they might organize a dance in a place where the loud music would interfere with the church service. Our priests would disappear from their parishes to destinations unknown. And the parish priest of the village of Makova was found dead, with his arms twisted and his legs broken...

The only good thing about those first Soviets was that they soon left.

2.

The Germans came. Although they did not interfere in church affairs, life became much harder. A famine began because a terrible hailstorm fell in our area. It destroyed everything. The field looked as if someone had plowed it over. As accustomed as I was to hardship from my fasts, I too suffered from hunger. The food sent to me from Boryslavka then was unusual: flatbreads made with thistle, lamb’s quarters, and nettle. It was all mixed with the dough. The flatbreads only looked filling...

Because of the famine, I could not move to Jarosław, where our gymnasium was being transferred. I was sad to part with my fellow gymnasium students, but it would have been even harder to leave the Przemyśl Cathedral.

I did nothing for show, but my zeal was noticed. Father Hrynyk, a canon of the bishop’s chapter, paid a lot of attention to me. Seeing me every morning at the Divine Liturgy, and whenever possible at other times of the day, the priest understood without any explanation from me that I wanted to become a priest. But he still asked.

And there was an incident. A simple woman, very devout but a holy fool, attended the Apostleship of Prayer. She even went barefoot in winter. Perhaps she didn’t even feel the cold.

One day, the three of us met in the cathedral’s narthex—Father Volodymyr Savka (or Savko?), the leader of the Apostleship of Prayer, that woman, and I. The priest asks her:

“Madam, tell me, what will become of this boy?”

“Father, why are you asking me such a thing? What can I say?” the woman stammered. The priest had asked jokingly, but she took it seriously. She says to me:

“Please cross yourself!”

Now it was my turn to be embarrassed. But I crossed myself.

“This boy will become a priest!” she proclaimed solemnly.

The priest-leader took her words seriously. I, for my part, was very pleased with this prophecy. I told Father Hrynyk about it. After that, the priest began to take even greater care of me. I started to eat from their kitchen.

At first, I lived in Przemyśl on Słowackiego Street with a Polish woman, then with a gymnasium professor of German, whom I helped around the house and in the garden. Towards the end of the war, they took me in at the chapter house, to live with the mitred priest, Father Vasyl Penylo. He was a professor at the seminary. And I had been studying there privately ever since I was in Przemyśl.

When Germany fell, the gymnasium returned to Przemyśl, and I continued my studies. The Soviets returned and got back to their old ways. In the spring of ‘45, they arrested our bishop. The Poles began to deport the Ukrainians. In Przemyśl, it was dangerous for us to even go out into the street.

In September, they let us go home to help dig up the potatoes. There was trouble in Boryslavka too. People were working in the fields and gardens, but they were constantly on the lookout for whether the deportations were coming. The surrounding villages were already being cleared out.

Misfortune came to Boryslavka as well. The army burst into the village. “Departure! Departure!” Crying, shouting, cursing. Within two hours, a long, sad procession left the village. On the carts were small children, flour, rusks, clothing, bedding. People walked alongside the carts. Tied behind the carts were the cows. It was a good thing that rumors of the deportation had been circulating for a long time, and people had been able to sell a lot. But much was left behind. The most important things: our native walls, our native church, our native graves—we could not take...

They did, however, take the icons and church items from the church. But our road of exile was our Way of the Cross. Our Savior, who was with us in the fourteen images of the Stations of the Cross, eased it for us. People took them apart and carried them carefully hidden, like precious treasures. We did not leave behind any liturgical, cantor’s, or other church books (the metric book is now kept in the Ternopil archive), nor any banners or chasubles. But the banners and chasubles were stored in people’s chests. Dampness and time destroyed them. They all rotted and became unusable.

On our cart, we carried the monstrance—a church vessel where the Most Holy Mysteries are kept (it was later dismantled and its parts stored in different places), the liturgical chalice (it was already over a hundred years old at that time, with the inscription “Dvulit”—the surname of our fellow villager who bought it for the church) and the Holy Gospel. These items are still in my possession, even though the Gospel was in the hands of the KGB.

...Our sorrowful, almost funereal procession, from which came the neighing of horses, the mooing of cows, and the cries of women and children, reached Nizhynkovychi—14 kilometers from our Boryslavka. In Nizhynkovychi, we dismantled the carts and loaded them, along with the horses and cattle, onto a train. We also boarded the same kind of wagons as the cattle. The train set off.

We traveled to the Ternopil region for almost two months. It’s not even three hundred kilometers! The train would stop for long periods in sidings. We ate from our own supplies. We couldn’t cook anything. It was good that at every station we could get “kipyatok” (boiling water). We were not accompanied by either police or military, but we couldn't escape because we had no documents, and our papers indicated our destination: the village of Dzhuryn in the Chortkiv district of the Ternopil region.

We arrived there in November. At the station, we received an assignment to the Buchach district, to the village of Barysh.

In Barysh, they settled us in the houses where Poles had previously lived. They were semi-ruins. In ours, the stove had collapsed, the windows and doors were broken. Not every house even had a cattle shed.

It was very difficult at the beginning. As soon as we arrived, we went to the fields to finish harvesting the corn that had been left without owners. We had to feed the horses and the cow with something. We still had our own flour at first. We had a little money, because we had sold some things in Boryslavka before the deportation—we bought potatoes. A Cossack is not without his fortune, and God is not without His mercy. Somehow, we survived the winter. In the spring, they gave us land—not as much as at home, but enough. They gave us seeds. The people started spring planting. We struggled through one more summer, and by the next spring, we had our own.

The local people—those who were nationally conscious—helped us get back on our feet. The ignorant people treated us with contempt, as if we had left our homelands of our own free will.

Half of Boryslavka was in Barysh. The other half was in the Rudky district. People wrote to each other, visited each other. But it was bitter, because for many generations they were used to living together.

Our people were settling in to their new places. In Barysh, I could not fulfill my calling. After the Epiphany, I went to Lviv. My aunt lived there. They registered me at her place, at 19/20 Khmelnytskoho Street.

I needed a document of education, so I immediately went to school, to the tenth grade. The principal was one of our own. I told him I wanted to be a priest, and the principal was sympathetic to me. The school was on Kalinina Street, now Zamarstynivska. After graduating, I entered the paramedic school on Kamenarska Street. I had loved medicine since childhood. I thought this passion of mine would be useful to people, because I knew how much our villages lacked medical care. I wanted to heal not only the soul, but also the body.

The year 1946 is a sad one in the history of our Church. Since the previous year, after the arrest of all our bishops and many priests, the persecution against Her was already overt. It reached its peak on March 8–9, 1946, when that pseudo-synod was convened in Lviv. Lviv wept then. After the “synod,” we stopped going to St. George’s Cathedral—it was in that church that the gathering had taken place.

I knew that Father Havryil Kostelnyk attended the Preobrazhenka (the Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord, in the city center, near the Zankovetska Theater). I went there specifically to meet him. As he was walking from a side altar to the sacristy with the chalice in his hands, I crossed his path:

“What have you done? How did you dare to betray the Church like that?!”

The poor man looked at me with sad eyes, but said nothing. He went his way, and I went mine.

I noticed two civilians watching me intently. I realized they were NKVD agents. But they didn’t stop me. I don’t know if they heard what I said to the priest.

The Muscovites did not expect to destroy our Church officially so quickly and easily. After all, that “synod” was not unexpected; its “initiative group” had been working for a whole year. The Muscovites calmly arrested our priests and bishops—if only there had been some resistance, some protest. At that time, the Muscovites were still a little afraid of the world. The world might have stood up for us, but we were silent as fish...

There was not a single Greek Catholic church left in Lviv. Of two evils, I chose the lesser. I could not go to a Moscow Orthodox church controlled by the Bolsheviks. I went, like many of our Greek Catholics, to a Polish church, to the cathedral.

I went to Mass every day, and frequently went to confession and received Communion. My spiritual directors were Father Niszczomski, and later—Father Krynicki. But I didn’t speak Polish with them, even though I can. They understood Ukrainian and answered me in Polish.

It was very bitter, after we had suffered so much from the Poles, to go to their church. And the Poles—are always Poles. Even the priests. They showed no sympathy for our plight, but set about Polonizing us. They started with our children. We complained. It reached Rome, but Rome changed nothing. We stopped going to the Polish church and started gathering in private homes. Our priests, who had lost their official work but had not signed up for that Muscovite Orthodoxy, celebrated services underground. Thus our Church went into the catacombs.

There was no question of any legal theological studies then. They could, of course, have sent me somewhere to Odesa or Muscovy to study to be a “batyushka” (Russian priest), but I was faithful to the faith of my fathers.

The tragic events of 1946 only strengthened my desire to become a priest. Back in Przemyśl, I had collected a large spiritual library, and I brought it with me, along with my notes from the seminary (I still have them). I studied on my own.

In those years, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army was still strong. I had an interesting meeting with several of its leaders.

I found out that in Yakubova Volia, not far from Drohobych, Father Pavlo Pavlish was the parish priest. He had baptized me and was my catechist until the second grade, then he left the village. I studied in Przemyśl with his children, who were my age. I went to visit the priest.

The priest had remained in the church because he had signed on to Orthodoxy. He told me it was on the orders of the insurgents, whom he was helping. This was evidently true, because in 1965 the priest left Orthodoxy. He was Orthodox only on paper. Before God and his own conscience, he was a Greek Catholic priest until his death. He died at the age of 92.

At that time in Yakubova Volia, the priest introduced me to some partisan commanders. From them, I learned that they were publishing a partisan newspaper-bulletin. Later, we met in the forest outside the village, and I gave my patriotic poems for the bulletin. I don’t remember them anymore. I know that one was called “Forward.”

Our paramedic school also had connections with the underground. I had many patriotic comrades, and they helped me a lot. The need for their help was great.

About a month after my arrival in Lviv, my father visited me. He brought a long list of medicines and prescriptions. Those prescriptions had the stamps and signatures of the doctor from the hospital in Barysh. But my father didn't hide from me that the medicines were for the partisans. Back in Boryslavka, my father had been a stanychnyi (organizer of food, medicinal herbs, and dressing materials collection) in the UPA. In Barysh, he immediately took up the cause again. The Sich Rifleman continued to serve Ukraine.

Father would bring lists of medicines and prescriptions, and my trusted friends from my school and I would run around Lviv’s pharmacies and buy it all up in small quantities. We couldn't buy everything in one pharmacy, as that would be suspicious.

Once a month, my father would come with a fellow villager (also from Boryslavka). They would return from my place with full suitcases.

I kept everything I bought at my apartment. So as not to endanger my aunt, I moved from her place to 28 Kalinina Street. I stayed with a Polish woman, an elderly lady. I had a room with her. I felt safe. For a time...

We lived on an upper floor. One day, an old grandmother from downstairs came to us and said that her tenant wanted to talk to me. I agreed. And she came. She looked to be 25 or 26 years old. She said her name was Miss Nadia, from the Lonchyn priestly family, and that she had been imprisoned at Lontskoho Street for 9 months. They had taken her for collaborating with the Banderites, but found no proof and released her. Nadia said she could put me in touch with the insurgents.

I refused. Nadia seemed very suspicious to me.

3.

Before that, only our countryman had come for medicine, without my father. This time, besides the medicines, I bought paper and ribbons for typewriters for Barysh (I had sent the typewriters earlier). On the way back, the courier was detained by the NKVD. I don't know what happened, but they released him with everything. He didn't confess to my father...

After this incident, that Nadia started visiting frequently. I tried to enter and leave my lodgings unnoticed. I traveled just as secretively to Barysh for the Christmas holidays in 1947.

The journey was difficult. It wasn't always possible to squeeze onto a train back then. I often rode on the roof or stood on one leg, holding onto the entrance handle. But somehow I made it to Buchach. From Buchach to Barysh is 30 kilometers. There was no way to get there further. I went on foot...

We were sitting at the Christmas Eve table when there was a knock at the door. We open it—and there on the threshold is... Nadia!

I was very surprised. My parents were surprised too. They knew I wasn't going to get married, that I wanted to become a priest. And here was Nadia! As if she were my fiancée!

I only asked:

“How did you get here? Your first time in the village, and you didn't know the way?”

“I asked people.”

She was invited to supper. I kept asking:

“Miss Nadia, why did you come, why did you come?”

She wouldn't answer. She dodged the questions. The carolers arrived.

They took Nadia caroling with them. In one house, they found the district leader Hrom with some insurgents. Nadia said she was a priest’s daughter, and they treated her as one of their own...

When Nadia went caroling, I told my relatives that both Nadia and her arrival seemed suspicious to me.

When I returned to Lviv, I began to inquire cautiously about Nadia. It was confirmed that she was indeed the daughter of a priest and that she had been in prison.

Everything became clear in the first weeks of Lent. Her friend ran up to me and handed me a crumpled piece of paper. On it was Nadia’s denunciation of me and others to the NKVD. Nadia had thrown the note into the stove when her friend unexpectedly entered the room, but the friend pulled it out.

Everything was clear. I was not expecting anything good.

On April 1, 1947, I went to send a telegram that I would be coming to Barysh for Easter. The post office was on the same Kalinina Street, around number 30. I hadn't even finished writing on the form when four men approached me. They showed their credentials:

“You’re under arrest! Come with us!”

They led me out into the street. They walked me. Two behind, two in front. In plain clothes, in trench coats. Hands in their pockets. In their hands, obviously, were revolvers.

They took me all the way to Horkoho Street, to the NKVD headquarters. On the second floor, they handed me over to an investigator. Interrogation started immediately. With insults, curses, with vile Russian swear words. “Last name! First name! Patronymic!...” They asked about my grandfathers, grandmothers. “Connection to the gang: who, when recruited...”

I didn't hide that I had bought medicine, but I said that I had bought it for the hospital, which I knew from the stamps on the prescriptions. That was strong evidence. I didn't know that they already knew everything...

Later I found out that about a week later, on Easter itself, they arrested my father and that other man.

It's terrifying to recall those interrogations. They beat me. With fists—in the back, in the head, in the stomach. On the neck—with a “club.” They put me “to the wall”: facing the wall with my hands up. I stood like that for hours. When my hands dropped, they beat me. There was nothing human in them. It was as if a person had fallen into the hands of the devil. They had not the slightest mercy, not the slightest. For about a week at the beginning, I was in solitary confinement. Then they threw me into the basement, into a common cell.

So many people. Lying side by side on the concrete floor. Not everyone had something to lie on. A small window, about twenty centimeters, and that with a basket-like “muzzle,” only a sliver of open sky shone from above. They didn't take us to the bathhouse, didn't give us clean linen. They fed us starvation rations—salty and rusty herring, a piece of wet bread, a soup of half-rotten potatoes and beets... And the bedbugs ate us. But very soon they had nothing left to eat on us. There was no peace in the cell day or night. They took people for interrogation at night too. They would return with fresh beatings, groaning.

One of my interrogations was on Easter.

They took me to the investigator. They stood me facing the wall. The investigator was writing something, and my thoughts were on the outside. I remembered the Easter holidays in my native Boryslavka. Suddenly I hear:

“Christ is Risen!”

“He is Risen Indeed!” I answered solemnly.

A blow with a club on my neck, just below my head (they knew where it hurt most) brought me back to reality. I lost consciousness. Later, I could barely make it back to my cell.

Those inhuman beasts mocked the most sacred things.

But even in these inhuman conditions, we tried to be human. We did not forget God. Morning and evening—a common prayer. We prayed separately too. We sang in a low voice—for what is a Ukrainian without a song? Of course, they didn't give us any books or newspapers. So we told each other what we had read. We recounted stories from the Bible, from Holy Scripture, our historical novels. Here, in the cell, were my first attempts at catechization, at preaching.

About a month before the trial, they moved me to an upper floor, to a smaller cell. Among us was our famous partisan Soroka (he was recently reburied near Drohobych). He was a sturdy man of about thirty, well-built physically, and even better—ideologically. A conscious, intelligent, intellectual man. One could feel that he held a high combat position.

Soroka was preparing an escape from the cell. We stood “on lookout,” while he chiseled out the bars with a metal object. We planned to escape on a rainy and stormy night. There wasn't much left to chisel, the two lower crossbars were already free, when someone informed on us. We were all put in punishment cells. There, they kept us only in our underwear; during the day there was nothing even to sit on; once every three days—a glass of water and a hundred grams of bread.

I was kept in the punishment cell for a week. Then I was moved to another cell, but Soroka was no longer there.

Once during the investigation, they arranged a “confrontation” for me. They bring me to the investigator, and there is Stefa Kryvulets, my relative. They had also been deported from Boryslavka, but to the Lviv region, to the Rudky district, the village of Pidhajtsi. I had been there before my arrest, visiting my relatives.

I was very surprised when I saw Stefa. I went straight to her:

“Stefa, what are you doing here? You haven't been anywhere, you're not connected to anyone. Be careful they don't entangle you. You haven't been anywhere! You don't know anything!”

The investigators didn't expect me to behave like that. When they came to their senses, they started beating me. That was probably the worst beating I got.

It was only in the camps that I learned that my warnings helped Stefa get free. They held her for another week and then released her.

The time for the “trial” came. It was in the same prison. They took me to the courtroom. Here I met my father. The man who used to come to Lviv with my father was also here. They didn't conduct any confrontations with them during my investigation, didn't mention them at all, but from the protocols I guessed that my father was also behind bars.

We were seated behind a barrier. The guard didn't let us exchange a single word.

A military tribunal tried us. The trial was very short. The three of us were given 10 years of camps and 5 years of deprivation of rights (in camp jargon, “a hit to the horns”). Article 54-1 a-11—“treason to the motherland.” The partisan article. With this article, the commune dealt with all the soldiers of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

After the trial, they transported us to the prison on Lontskoho Street. They drove us in an open truck. It was June. Summer was in full swing. The sky was clear above. It was hard to return to the hell of prison again.

Even before the trial, I knew I wouldn't be released; I only expected a longer sentence. That's why I felt a sense of relief after the trial. I didn't “implicate” anyone, no one suffered because of me, even though I was beaten or tortured in other ways at every interrogation. And it was possible not to endure those beatings and abuse. In this prison, they broke people’s fingers between doors, they hung girls by their hair. Father Yavorsky “confessed” under torture that he had shot a general, although he had never been in the army, had never held any weapon in his hands, and couldn't have even killed a chicken.

Whoever survived those physical, moral, and spiritual tortures and lived—that person experienced the great miracle of God’s grace.

The prison on Lontskoho Street was different only in that we were on an upper floor and on a wooden floor. The bars, the slop bucket, the rules—all the same. The cell was overcrowded, stuffy. We were tormented by thirst, they didn't give us enough water, but they gave us very salty herring.

...The feast of the Most Holy Eucharist was approaching. I was very sad. On that day, when I was free, I would go to confession, to Holy Communion. But here... Yet the Almighty and the Most Pure Mother of God did not leave me without their care even within the prison walls.

What happened on Saturday, the eve of the Feast of the Most Holy Eucharist, I consider a miracle of the Lord.

And this is how it was.

During my sad reflections, footsteps were heard in the corridor, a key grated in the door, the door opened, and a guard pushed a man into the cell. An intelligent face. Exhausted, but with an unbowed expression.

The door locked.

“Glory to Jesus Christ!” the newcomer greeted us.

We understood that he was a priest. He immediately confirmed our guess:

“I am Father Tsehelsky. I have everything needed to celebrate the Divine Liturgy. Whoever wishes to go to confession, please come forward.”

The entire cell went to confession. There were about 50 of us in it.

I confessed among the first. My happiness knew no bounds.

I served as an acolyte for the priest during the service. The priest knew the Divine Liturgy by heart. To have any kind of booklet or notebook with him—that was out of the question.

Our Communion was very moving. The priest had wine in a small bottle with the label “Heart Drops.” A small cup served as the chalice. The prosphora was real.

In the morning, before “reveille,” the cell door opened with a bang. Then, as per the prison “rules”:

“Who’s last name starts with ‘Ts’?”

“I am,” Father Tsehelsky responded.

“Out, with your things!”

It turns out they had mistakenly placed him in our cell.

That's what they thought, that they had made a mistake. But it was God’s Will. It was a magnificent Grace of God for me.

I met with Father Tsehelsky in Lviv after my second imprisonment. God granted him a long life.

Sometime in September, a group of prisoners, including me, were put into “voronky” (NKVD prisoner transport vehicles) and brought to a camp that was 6 kilometers from Mykolaiv in the Lviv region, about 30–35 kilometers from Lviv.

This camp was in a former Roman Catholic orphanage. It was freer there. We could walk around the fenced-in yard, go from barrack to barrack.

Here I met my father. Neither he nor any of the other prisoners complained about their fate. People knew how to carry themselves, because they knew why they had gone to their torment. We only worried very much for my mother, for my younger brothers and sisters. While my father was in captivity, my youngest brother was born. My mother hid with him among people for a year...

My father and I were in different brigades. After work, I would go to my father’s barrack.

There, near Mykolaiv, we were building two-story residential buildings with 4 apartments each. At first, my father was not on the construction site, but worked in the gardening brigade. After they dug up the potatoes, they put my father in the carpenters’ brigade.

I had no construction skills, so I was a laborer, a loader. I pushed cement, bricks, mortar, and stones in wheelbarrows and carried them on stretchers. It was hard work.

Once, a boy of about seventeen, a Boyko from the Drohobych area, told me to come to him after supper. It so happened that I couldn't. The next day, he escaped from the camp. Later, they found his jacket near the pipe through which water flowed out of the zone. He had apparently escaped through that pipe. I regretted that I hadn't escaped with him. I would have persuaded my father too. We have large forests...

At the end of the year, we were transferred to the Lviv transit prison. We were packed in there like herrings in a barrel. It was a good thing they didn't keep us there for long. They loaded us into a freight train.

They transported us in wagons built for carrying cattle. But they had installed bunks on two sides, bars on the windows... Such a wagon should stand somewhere in Galicia as a monument. As a memory of those terrible times when thousands, millions of innocent Ukrainian people were transported in those cattle cars to Siberia and the Kazakh deserts. Was it their fault that they loved and defended their land, that they wanted to pray to God in Ukrainian?

4.

On the train, too, we suffered from thirst. They gave us salty herring. They withheld water. On purpose, to make people suffer. People licked the nails that held the wagon planks together, because frost formed on them.

During the journey, the convoy gave us no peace. First, they would tap the wagon with wooden mallets: to see if anyone had torn a plank, preparing an escape. Then they would herd everyone to one side of the wagon and make them run to the other, counting. They counted with the same mallets: hitting everyone wherever they could, and urging us on: “Skariey, skariey” (Faster, faster). They laughed, they swore. That was their entertainment...

One night, they woke me up. We took turns looking out the small window—a city was lit up. We realized it was Kyiv.

The train rumbled over a bridge. What a commotion broke out in the wagon! “Dnipro! Kyiv! Dnipro!” we shouted, rejoicing like children, forgetting that we were not traveling to our capital as welcome guests, but that they would transport us through it further, to a distant and cold foreign land. A song arose: “Moscow has fallen, and the city of Kyiv is now the capital!”

When the gardens around the whitewashed houses disappeared from view outside the window, and instead of neat little houses, “izby” of blackened logs appeared, we understood that this was already a foreign land...

Christmas found us on the road. It was a sad caroling...

Exhausted by the journey, the frequent stops, the long waits in sidings, we finally arrived in Chelyabinsk.

They crammed us into barracks—large buildings with no internal partitions, with two-tiered bunks along the sides. Between 200 and 300 prisoners lived in one barrack. On the sides of the barrack, two stoves seemed to smoke, but they didn't give off heat. People slept in their clothes, on bare boards, without mattresses.

The walls were red with blood. Bedbugs ate us alive. People caught them and crushed them against the walls.

In the camp, everyone was clothed. But in old, greasy, often blood-stained clothes. Everything was gray, the valenki (felt boots) were old and misshapen.

Here, behind the barbed wire, was a true international. There were people from every nation of that Soviet Union, and there were so many Ukrainians that it seemed they made up at least two-thirds of the USSR. After the war, there were Germans, Hungarians, Italians, Japanese, and Chinese among the prisoners. No one formed separate brigades; everything was mixed together: the “friendship of peoples.”

Our camp was building up Chelyabinsk. I was a laborer. But the work here was much harder. Because we were building five-story buildings, and there were no cranes to lift the loads. We served as the cranes.

To this day, it's terrifying to remember those steep ramps—planks with slats nailed across them. We walked up those ramps to the fourth, the fifth floor. Our arms couldn't take it. Once, right in front of the brigadier, I dropped a stretcher. The brigadier ran up and punched me in the face. He was also a prisoner. A Muscovite.

He hit me hard, I almost fell, but I stayed on my feet. I looked at him, without malice. With pity. He turned away, ashamed. Later, he looked for lighter work for me.

It was a difficult post-war time. All of Muscovy was hungry. What can be said about the prisoners? Some received parcels from home. No one sent me any.

My first camp Easter was in Chelyabinsk. On Easter Sunday, we gathered together, and after a common prayer, we ate the bread we had set aside from our meager camp rations. Tears rolled down our cheeks as we sang the resurrection hymns. Our thoughts were far from there, in our native land.

I suffered on the construction site for almost the entire year. Before Christmas—a transport. They took us to Bashkiria.

At first, I was at a logging site. The camp was in a valley. We would walk up into the mountains to the felling site, and if it was far, we would ride in open trucks. At the site, we would clear the snow from the tree trunk, cut it as much as needed with hand saws, then push against the tree with poles. When it fell, a cloud of snow would rise. Then we would chop off the branches and twigs, and cut the trunk into logs. It was hard to carry those logs down, to stack them.

The snows in the forest were deep. People would fall into them. I, too, was in a snow pit. It was lucky that others saw me fall. I would not have gotten out of it by myself.

They didn't give us a day off every Sunday. When it snowed, they would herd us out to clear the railway tracks and roads. It would seem that snow is light, fluffy, but this work was also very tiring.

I thought there was no harder work than logging. But then they put me in a stone quarry. There were stone mountains there, and they were supposed to build some military objects on their site later, so we were quarrying those mountains. The tools were simple: a crowbar, a pickaxe, a chisel, a hammer.

But in Bashkiria, it was much easier for me than in Chelyabinsk. For my soul. Because in the same brigade with me was a priest. He was a lecturer at the Lutsk Roman Catholic Seminary, Father Józef Pukowiński. He was a noble, highly educated dignitary. The father was completely unaccustomed to camp conditions. The frost bothered him greatly. The father suffered a lot, but he did not get sick.

Camp conditions cannot be compared to seminary conditions, but in me, the father had a capable student. He was pleased that I wanted to be a priest and gladly helped me. The father spoke Ukrainian well. So as not to forget the language, I also spoke Polish to him.

We used every moment. The father taught me when we rested for a few minutes in the quarry, leaning on a crowbar or a shovel, and in the evenings in the barrack. Most of all—on Sundays. Every Sunday, the father celebrated the Divine Liturgy on his bedside table. He celebrated in Latin. He heard confessions, gave communion, but under one species. The camp bread served as the prosphora, as there was no wine.

In Bashkiria, I greatly regretted not having the opportunity to draw. The Lord gave me a small measure of this talent. No matter how hard the work was, I admired the beautiful landscapes. As if I knew that I would soon not see them.

And so it happened. In the spring of 1949, a freight train took us to Kazakhstan, to Dzhezkazgan, into a sea of sand. Wherever there was a patch of earth, it was covered with luxurious red tulips. We admired them as we rode. But within a few weeks, everything had burned up under the sun.

Sandstorms are a terrible thing. But they hid me from them very far away, or more precisely—deep down. In a mine. To extract copper ore. In the Pokrovskaya mine, number 39.

First, they would drill and blast the ore, then lay tracks, and on those tracks, we, the tunnellers, would push wagons into the face. There, they would load the ore onto a scoop with a scraper, throw it from the scoop into the wagon, and when it was full, we would push it back. In one shift, we had to fill 30 such wagons.

In Dzhezkazgan, I had someone to learn from. Here there were Father Dolishkevych and Father Pushkash from Transcarpathia. There was also a professor of Theology from Belarus, a Roman Catholic. Unfortunately, I don't remember his name. Father Dolishkevych was later killed in the Dzhezkazgan uprising. He was crushed by a tank... He was thrown behind bars because he did not sign on to Orthodoxy. He bravely set out on his Way of the Cross, leaving his family at home. Now his son is a priest.

Because in our level the ore-bearing layer was about four meters thick, it was that many meters, or even more, to the ceiling in the drifts-passages. The ceilings, unlike in coal mines, were not reinforced here, only in dangerous places was the ceiling supported by pillars. But that was not enough, and rocks often fell from the ceiling. Sometimes so much that it blocked the passage.

One such cave-in caught me and some other guys in the mine. A rock that broke off from the ceiling tore off my comrade’s leg. Another rock (we weighed it later—it was 20 kilograms) fell on my head, bounced off my helmet and hit my shoulder, but not too hard. The blow to the head stunned me, but I quickly recovered.

They brought me and the wounded man to the surface. They wanted to support me as I walked, but I refused. The mine chief, a short, dark-skinned, surprisingly humane Kazakh, pointed at me to his colleague:

“I knew nothing would happen to him. He’s a believer! Whenever he goes down, he’s always crossing himself!”

And so it was. Entering the elevator, I would, without hiding it, cross myself three times. No one laughed; they took it seriously, but did not imitate me.

When that cave-in happened, a commission from the Ministry of Health came to our camp. We were surprised by their high cultural level, their impeccable command of the Russian language. They summoned the prisoners. They asked not only about health. They inquired about camp life, about the relationship between the prisoners and the authorities. They inquired in detail. They asked me many questions too, when they summoned me. After examining me, they transferred me to another category, for work on the surface.

The commission worked and left. Very soon, another commission from the Ministry of Health arrived. A real one this time. The previous one had been organized by... British intelligence! Espionage!

The authorities didn't tell the prisoners about such a mess. And since my papers said that I was being released from the mine, I did not go underground.

I didn't go to the morning "razvod" (work assignment), but hid in the zones. They were separated from each other not by fire-lines, but by high walls with wickets. Prisoners guarded the wickets, and they let me pass. My hiding ended in a punishment cell. They put me in for a week. The regime was the same as in a prison punishment cell: once every three days—a hundred grams of bread and a glass of water.

After the punishment cell, they transferred me from the third camp point, the mine one, to the first. They were afraid that if I started to rebel again and not go into the mine, other prisoners would follow my example. After all, it was written in the papers: work on the surface. And for them, papers were more important than a person.

I went back to breaking rock. The work was much harder than in the mine, but safer. And there was the sky above my head.

And again—for this transfer, as for the fact that I was not killed or injured in that cave-in, I thank the Almighty. He was preparing a great event for me in this camp. In the first camp point, there were also priests. Our Greek Catholics, Polish Latins. Here I became friends with a priest from Moldova. A Basilian, a Greek Catholic. Someone in his family was of Italian descent, someone of Romanian.

In December of that year, 1949, a prisoner-bishop, whom the father knew, was transferred to us. The Bishop’s father was from Muscovy, his mother—Italian. When the Russian Empire collapsed, he emigrated with his family. He entered the Jesuit order. He studied, taught philosophy at the Russicum in Rome. I don't know how he ended up in Lviv, or who consecrated him a bishop. Obviously, it was done secretly—by the Servant of God Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, because the bishop often mentioned him. The Metropolitan sent him for missionary work in Muscovy. The bishop was tried as a Vatican spy.

He was a mobile, sturdy man, similar in stature to Patriarch Josyf Slipyj. With a reddish beard. He was about 50 years old then. He introduced himself to me as Viktor Novikov. He hoped that we would get out of the camp, that better times would come, and that we would meet in Rome. He gave me his address in the Eternal City: via Spiritus Sanctus, 5 (Holy Spirit Street, 5).

By God’s Grace, times changed, and I looked for the Bishop in Rome. He was not at the given address; at the Russicum, they confirmed that indeed, a Kyr Viktor Novikov had taught philosophy there. They said he had two other surnames: Makovsky and Kholyava. Obviously, Novikov was his real one. But he was not in Rome. No one knew about his further fate.

...After several long conversations, which had the character of an examination and gave the Bishop a corresponding impression of me, he said that he would give me diaconal ordination.

I began to prepare for the ordination. I went to confession often, received the Holy Mysteries. The bishop himself gave me my retreat.

In the camp conditions, I could not even dream of clothing appropriate for this solemn act. But I wanted to distinguish myself somehow on the outside as well. I had a long white shirt. It served as a dalmatic. A friend of mine, who worked in the laundry and was in on the secret, cut a towel lengthwise and sewed an orarion for me from it.

The solemn and memorable day for me arrived. It was January 1, 1950.

The ordination took place during breakfast. The bishop knew the main prayers by heart, most importantly—the form of ordination, “The Divine Grace.”

After the ordination, I was on cloud nine. I forgot that I was in captivity. It was a great joy for me that even by such a difficult road, the Lord was leading me to the priesthood, that He heard my fervent prayers.

Of the priests, only that one father from Moldova was a witness to my ordination. The Bishop himself told our priests about my diaconal ordination. They received this news with joy.

Having received the first degree of the priesthood, I could work in the camp within the limits of my diaconal authority. It gave me the right to preach, to prepare people for confession, to celebrate molebens: vespers, matins, akathists.

The Bishop said that he would give me priestly ordination at Easter. Both he and our priests were preparing me for it. They told me things from memory. Some managed to get spiritual literature by some means. I devoured it eagerly.

But during Lent, in the middle of the night, the Bishop was taken from us. I can't recall whether it was before or after the Easter holidays that I too was sent away on a transport to Spassk.

5.

In Spassk, the camps were in the Valley of Death. They drove us for a long time through the sandy desert, in open trucks. The wind carried sand. It filled our mouths, our eyes.

There were over 20,000 prisoners in the Valley of Death. There were many priests there. I met Father Ivan Hotra there—a Basilian, Father Mysiak—the hegumen of a Studite monastery. The “true Orthodox” from Muscovy, as they called themselves, were also being punished for their faith. There were also Latin-rite priests, among them Father Turkus from Latvia.

Next to our concentration camp was a women’s concentration camp. There were nuns there. Between us was not a fire line, but a wall. We could communicate through a wicket gate. We would pass notes to the sisters, informing them of the time of our Divine Liturgy, so that they could join us in prayer. At the agreed time, they would come out to a small hill in their zone, so that they could be seen from our zone. They would express their sorrow, beat their breasts. Father Hotra would give them absolution, bless them.

In Spassk, there were old, depleted, forgotten quarries. We would gather there for prayer. Here we were truly like the first Christians who prayed in the underground Roman catacombs. As a deacon, I celebrated vespers, matins, and akathists there. Many people gathered. The guards found out, chased us away from there, but we would gather there again later.

Life was hard, the climate unbearable. People, exhausted by unbearable labor, were dying in large numbers. Two brigades of prisoners, in two shifts, did nothing but dig graves. The Valley of Death lived up to its name.

It seemed that there would be no end to this misery and sorrow, that our people would perish in these sands and in those boundless taigas, in those bare tundras.

We saw those terrible deaths, but in our hearts, a hope flickered that God would help us get out of this hell on earth.

One evening, after prayer, I was pondering the unfortunate fate of our people. I took it to heart. I thought: what will become of the people who suffer here? What will happen to the concentration camps? Will this ever have an end?

With these thoughts, I fell asleep.

And I dreamed that I was in a large square. I am sitting on the ground, drawing in it with a stick and thinking: My God, what will become of this nation?

Suddenly, a person of majestic appearance stands before me. His beard and the hair on his head are gray, almost silver. His clothes are so heavenly. Like a spirit. His supernatural power was palpable. He says to me:

“Child, what are you thinking?”

I was afraid to utter a word, I was terrified. The majestic old man then says:

“I know what you are thinking. You are thinking about what will become of my people. What the end of this will be, what their fate will be. Stand up.”

He takes the stick from me, and takes me by the hand to the middle of the square, and asks:

“What do you see?”

I look: before us is a large anthill. I tell Him.

“Watch what happens now.”

The old man with my stick, here and there—leveled that anthill. The ants—ran off in every direction with their little white pupae. The old man says to me:

“And now tell me what I have done.”

“You have leveled the anthill with the ground.”

“And what are the ants doing?”

“They are scattering. In all directions.”

“Yes. Now stand up and tell my people that soon the time will come when I will level all these concentration camps with the ground as well. And My People will return home.”

At this, I awoke. Sitting up! I was seized with fear. I knew I had gone to sleep lying down. I woke up—and I was sitting! I wake my neighbor:

“Ivan! Ivan!”

“What happened?” he asked, frightened. It was around midnight.

He was the first person I told my prophetic dream to. Mr. Ivan Smetaniuk now lives in Hoshiv.

I told this dream to my confessor, Father Hotra, to Father Mysiak, and to other priests. They all also took it as prophetic.

That dream was a great spiritual support for us.

I cannot say who appeared to me in the prophetic dream. Whether it was one of the Prophets, God’s messengers, or the Lord God Himself.

After my dream, we set to work even more zealously in the Lord’s vineyard. I had a prayer book, I cherished it very much. In addition, we had many services, psalms, handwritten. It was not always possible to take a book or papers with you. Therefore, I memorized a lot. I knew by heart the moleben to the Heart of Christ, the Akathist to the Mother of God.

Sometime in 1952, I had another prophetic dream. It also came true, but later. I dream then that I am in Rome. And that I am a bishop! It was very strange, because I wasn't thinking about any episcopacy then, I wasn't even a priest yet.

I dream that I, as a bishop, am preparing to celebrate the Divine Liturgy. And in St. Peter’s Basilica! At the tomb of St. Josaphat Kuntsevych! I am carrying the chalice, carrying everything to celebrate the Divine Liturgy. Not only that, I am going to the very place where, many years later, his holy relics were indeed solemnly laid. I enter the church, turn to the right side, enter the third or fourth nave...

It is known that the relics of St. Josaphat were in Vienna before the war, in the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church of St. Barbara. During the war, they were probably taken to Rome. But they were transferred to St. Peter’s Basilica, the most important Catholic cathedral in the world, during the second session of the Second Vatican Council, when, by God’s grace, the late His Beatitude Patriarch Cardinal Josyf Slipyj, torn from the Khrushchev concentration camps, was already in Rome.

In 1990, I, as a bishop, while in Rome, concelebrated the Divine Liturgy at the tomb of St. Josaphat with other bishops. My dream came true after 38 years!

I told only Father Hotra about that dream. Because not all of our priests, unfortunately, courageously fulfilled their duty, not all perceived my zeal in the same way, and if I had also told them that I had seen myself as a bishop in a dream...

I will also tell about a third dream, which I had in the same year, 1952, before my departure to the Altai Krai.

...I dream that I am in a vast space. Not planted, not sown. Like a desert. And in that desert, there are very many crosses. Different ones. Large, small. Iron, wooden. New, old. Straight, tilted. I understood that these are human crosses. Every person's. I became interested: is my cross among these crosses?

I started searching. I searched, searched for a long time. Until I got tired. My cross was not there. I approach one, a second, a tenth. I feel: this is not my cross, not mine!

Then I see—a tall cross stands apart, far from me and from the others.

I reached it. The cross was tall, oaken. At its foot—flowers. Delicate white flowers. They entwined the cross and its base. The crossbeam was also in flowers.

I stand before that cross, as if rooted to the spot. I think, I marvel. And suddenly my heart tells me: that cross is mine, mine!

I fall to my knees before it, embrace it, kiss it, wash it with my tears... And so in tears I awoke.

This dream told me that the Lord was preparing a special cross for me. Though adorned with pure white flowers, it would be larger and heavier than others.

My further path of captivity lay in the Altai Krai, in Olgerras. They were building some huge plant there, I think an oil refinery. Over 5,000 prisoners worked there—“udarnaya komsomolskaya stroyka” (Komsomol shock construction project)!...

In Olgerras, I was lucky. There was no medical worker on the site. Looking through my papers, as a newcomer, they read that I had studied at the paramedic school in Lviv. The head of the medical unit was Captain Shkuro. Of Ukrainian origin. He summoned me. I explained to him that my medical education was not complete. After talking with me, he determined that my knowledge was sufficient and handed me a box with medicines and everything necessary for providing first aid.

God helped me to become useful to people in this field as well.

Almost immediately after I began my paramedic duties, an incident occurred.

Just when Father Kuzyk, the brigadier Petriv from the Drohobych region, and an autocephalous priest from the Rivne region were in my medical unit, a sick prisoner named Vlasenko, from Greater Ukraine, came in. The brigadier lashed out at him:

“You’re constantly bothering the doctors, going to the outpatient clinics. Leave people alone! Get to work!”

I stood up for Vlasenko. I say to the brigadier:

“Mr. Petriv, a visitor has come to me. He has the right to do so. He came as a sick person. I am obliged to examine him.”

The patient complained of pain above the lower back. I asked him to take off his shirt, listened to his heart and lungs with a stethoscope. I didn't notice anything.

The priests and the brigadier watched my actions, snickering. I did my job. I told the patient to lie down on the couch, palpated his muscles. When I pressed on his sciatic nerve, the patient cried out, and very loudly. I realized that he had an acute inflammation of that nerve.

I asked Petriv to call the guard on duty. They found a car and sent the patient to the central hospital. Vlasenko was treated there for six months.

There was also a tragic incident: a person was electrocuted. I started to perform artificial respiration. They called a doctor from the civilian hospital. He arrived, looked:

“Colleague, don’t bother. He’s dead!”

He left. I continued. It was written in the instructions: perform artificial respiration for four hours! After three and a half hours, the person came back to life.

Once on the construction site, they were lifting hot tar with a winch, the bucket opened and spilled on the one who was lifting it. I gave first aid, sent him to the hospital. No inflammations, no abscesses. So, it was done sterilely.

Sometimes I had to take on the work of a surgeon. A man's skin was torn off his back, on his chest. It was hanging in strips. By the time that surgeon arrives... I took staples, fastened it together. Less pain already.

I also had to get into conflicts with the authorities. They refused to sign the injury reports I wrote. These gave exhausted and injured people the right to a short rest. Once, when the chief was very resistant to signing, I went to check the workplaces. The instructions gave me the right to do so. Meticulously checking compliance with safety regulations, I found a number of violations and shut down the entire site. The chief couldn't find anything to punish me for. The prisoners were given gloves, the trenches were reinforced, grounding was installed—in short, almost all the shortcomings were eliminated. After that incident, the chief would sign reports even for scratches.

I received thanks from the hospital for my paramedic work. But what pleased me most was that I could be of service to people.

In this camp, I also performed my diaconal duties.

There were many of our priests here. Besides Father Kuzych, there were Father Korzhynsky (now lives in Kolomyia), Father Mykola Zheltvay from Transcarpathia, Father Baslyadynsky, and one more priest whose name I don't remember. But, unfortunately, the spiritual life in the zone was very sluggish. The Jehovah’s Witnesses and other sectarians took advantage of this, confusing people. It was necessary to get to work.

6.

Before Lent, I ask Father Zheltvay to convene our priests on the nearest Sunday. Because before Easter, we need to hear the prisoners’ confessions, we need to constantly celebrate services in the barracks. Our pastoral work must be organized. I told the father that I would prepare the prisoners for holy confession, and preach sermons at the Divine Liturgies.

Father Zheltvay agreed with me and ordered me to summon the priests.

The priests gathered. When Father Zheltvay told them about my proposal, Father Baslyadynsky became indignant:

“What? That snot-nosed kid is going to boss us around?”

I didn't expect to hear that. I was hurt, but I didn't say a word. Father Zheltvay said:

“Reverend fathers, there are no snot-nosed kids among us. We cannot oppose God’s ordinance when the Holy Spirit speaks to us and has chosen the deacon to remind us of what we are forgetting, that even in prison we are not exempt from pastoral work. Our faithful are here, and we, as priests,

are obliged to work on their souls. And God has called us to the prisons only so that we may be among our own people, helping them, protecting them, giving them peace of mind. Therefore, this important matter is not the deacon’s matter. It is God’s matter. And we must submit to God’s Will!”

After our meeting, the prisoners received greater spiritual care.

In the barracks, between the bunks—services. Instead of the Holy Altar—miserable bedside tables. Confessions, Communion, catechization...

And I was transferred again to another camp point. We resisted the harsh camp regime. I participated in a six-day hunger strike. Unrest began in the camps. Our committee had already given the order for a strike.

We went out into the yard in the evening. Gunshots. With me was a boy of about 18. He was desperate to run. I tell him:

“Mykhailo, Mykhailo, we need to go the other way, they’re shooting from there!”

He didn't listen to me, tore himself away. He ran into the bullets. He was killed before my eyes.

Bullets are already whistling by me. I sat down against the wall. I pray...

In the morning, I went to where I had prayed. The wall in the place where I had sat was pockmarked with four bullets. Two were very close to my head.

A great miracle of the Lord, the great power of prayer!

After Stalin’s death (we were informed of it by the “liar”—that’s what we called the radio in the camp), I was transferred again to the third camp point. Again, I organize the priests. Here again were Father Korzhynsky, Father Baslyadynsky. We found Father Volodymyr Senkivsky here.

At this camp point, we took up catechization. We organized catechetical circles, took on as helpers boys who knew the Law of God from home. We prepared them to be catechists.

Our priests agreed to celebrate the Divine Liturgies, but without sermons. I gave the sermons. Watching me, Father Volodymyr Senkivsky said to me, perhaps with irony:

“Deacon, you’re leading us so much here, it seems to us that you are our bishop!”

“Father Volodymyr, please take into account that here, in the camp, I am your bishop!”

I answered immediately, without thinking, as if someone had put these words in my mouth beforehand. I said them and smiled, so there would be no tension. And the priest smiled. We ended it there at that time.

In April 1990, when we were welcoming our Beatitude Patriarch Kyr Myroslav Ivan Lubachivsky in Lviv, near the city hall, on his first visit to Ukraine, I met Father Senkivsky. We had met after my first imprisonment, when I was still a priest. Right there, near the Lviv city hall, he reminded me of our camp conversation.

“And in the camp, I took your words as a joke. But you see how it turned out: You really are a bishop!”

Strange are the ways of the Lord! By a difficult road You led me, O God, to the priesthood, to the episcopate. I thank You for not letting me stray from the path, weaken in spirit, lose faith.

In Olgerras, besides giving sermons, I also organized molebens to the Mother of God, to the Heart of Christ. I celebrated them myself, as well as matins and vespers. It was all done in secret.

But the authorities had plenty of “stukachi” (snitches) among the prisoners. They would report when a service or moleben was to take place, and an inspection would come. When it approached, the one we left to watch at the entrance door would run up, or shout from his post: “Atas!” (Look out!). We would then fall silent, sit calmly on our bunks, and everything would look as if the inspection had nothing to find fault with.

Still, the authorities locked me in a punishment cell for “religious propaganda.” I went to it with joy, with gratitude to the Almighty for rewarding me with this suffering as well.

After the punishment cell, Havryil, a university student, from Lviv I believe, approaches me. He tells me about a prisoner, a teacher from Greater Ukraine. His surname, I think, was Melnyk.

Melnyk was imprisoned as a nationalist. But he was a fervent atheist. He gathered supporters around him. They said they would build Ukraine without God.

And this was before August 14. According to tradition, on this day Saint Volodymyr the Great baptized Ukraine. I asked Havryil for two Ukrainian representatives from each barrack to gather on August 14 in a certain barrack.

A great many people came. Mostly young men. I addressed them with a sermon about the baptism of Ukraine. I explained to them the great importance for our State of accepting Christianity, that we did not cast off the yoke of paganism to put on a new yoke—atheism. This new yoke is even more terrible, because atheism denies the existence of the Divine.

After my sermon, not only did that atheist group disintegrate, but our lay catechists also got more work. Many boys from Greater Ukraine came to them, who were born under that godless, diabolical regime, having seen neither a church nor a priest, and many had not even heard a word about God at home. And they came to our catechists, asked them to write down prayers and parts of the catechism for them on a piece of paper.

To this day, now gray-haired, when they remember the camps, they warm their hearts with the memory of learning to pray there, and today they teach their grandchildren and great-grandchildren the prayers they learned in the camp from a scrap of paper written by our catechist.

Christian life blossomed, bloomed with lush flowers in our camps. Looking at us, Ukrainians, other nations in the camps also returned to God. They no longer greeted each other with “Dobryi den,” “Guten Tag,” “Zdraste,” “Labadiena” (“Good day” in Lithuanian), but “Glory to Jesus Christ!” resounded over the camp in different languages.

When we celebrated services or I preached in the barracks, we did not ask foreigners to leave. All nations, Christians of different confessions, even Muslims, listened to me.

The Muslims, knowing Russian, understood my sermons in Ukrainian. There was nothing in them that contradicted their Quran. When I said that we would break free from this captivity and go to Ukraine—they then thought of their own native land.

There were not many Muslims in the camps, they did not have their own preacher, and when they had something on their minds, they turned... to me.

Once, a Muslim, about 24 years old, an Afghan I think, asked me to explain an unusual dream. He dreamed that unknown people had cut off his head with a sword. Then all his consciousness was in that head. They carried that head over the barbed wire, to his native Afghanistan. From a height, he admires the lush greenery, the flowers, and on those luxurious grasses and flowers, his blood drips from his head. He asks me: what does this dream mean.

“My friend,” I tell him, “I do not interpret dreams, and it is difficult for me to answer you. But it seems to me that you will be home this year. And since you dreamed of grasses and flowers—it will be this summer.”

God made it so that it happened. An amnesty came, he was released. His joy knew no bounds. He came, thanked me with tears in his eyes. I told him that it was not my merit, but God’s grace. But he went around to his people:

“The mullah predicted it for me! The young Ukrainian mullah!”

That incident further strengthened my belief: God is one.

Ukrainians, how long will we divide our One God?!

I also remember unpleasant things from that camp. The Transcarpathian priest Halayda comes to me in tears:

“The ‘blatnye’ took my parcel. And it had raisins for wine!”

We made wine for Communion from raisins. I’ll tell you right away how it was done.

The raisins were washed with cold boiled water, put into a jar, and covered with water just enough to cover them. The jar was tied with gauze and hidden in a not too warm and dark place until the raisins absorbed the water—as much as the grapes had juice before drying.

When there was no water left in the jars at all, and it had all passed into the raisins, it, and this was now juice again, was squeezed through gauze, strained, and poured into bottles. The bottles were closed with a cork and left for a week or two to ferment. You just had to watch that the cork didn't pop out. Because it once did pop out, and so loudly that the guard, who was on inspection, ran away in fear: he thought someone was shooting. But that was already in the Mordovian camps, when I was serving my second sentence...

So Father Halayda came to me in Olgerras, saying the blatnye had taken his parcel. The blatnye are a type of common criminal. But the worst thing was that they weren't real blatnye; we had already chased them out of the camps by then (much has been written about the struggle in the Soviet special camps between common criminals and our political prisoners), but these were our own boys who had gone astray under their influence in the camps.

I find those boys: