A SOUL-MURDER FACTORY

I was born in the village of Verbivka, Ruzhyn Raion, Zhytomyr Oblast, into a peasant family. My great-grandfather Vitsko and grandfather Herasym were “dekulakized” during Stalin’s “Great Break”: their land was taken, they were thrown out of their own well-built house, their farm tools, grain, and fine purebred horses were confiscated, and they themselves were forced to live in a dugout. The artificial famine of 1933, unprecedented in world history and orchestrated by Stalin’s clique, finished off these glorious ancestors of mine… My father, Mykhasko, as an “enemy element,” was taken into the labor army (which was equivalent to imprisonment) right after he and my mother married. Later, for protesting against the arbitrariness in this “army,” he was sentenced to 6 years in the camps and transported to Siberia. My father was 22 years old then. My mother was left with a small child in her arms, who soon died (their son Kolya); she wandered, dependent on the charity of others. The collective farm authorities persecuted her, imposing exorbitant taxes on her as the wife of a “kurkul” [kulak]… To this day, my mother remembers the address to which she sent letters to my father: “Ussuriysky Krai, Bamlaga station.” (My mother passed away on November 18, 2007. – V.O.)

My father miraculously survived, although on the way to the place of punishment, dead prisoners were thrown from the train cars in stacks. It was so cold in those cars that your head would freeze to the ceiling, and for an entire car, they would throw in a frozen, brick-hard loaf of bread. During this transport, my father’s hair (“his curly forelock”) completely fell out, and when he climbed the steps, he had to lift one leg and then the other with his hands… My father was saved by his innate, exceptional skill as a carpenter, as well as by the fact that he began working as an orderly for a kind camp doctor who treated my father very well, in a humane way, stood up for him, and even allowed him to wear a Ukrainian *chub* [forelock], which eventually grew back… So, thanks to his diligent work and the protection of the doctor-supervisor, my father served half his term. He even wanted to move my mother there, to the Far East, but he was drawn back to Ukraine, to his native Verbivka… It was 24 months before the infamous year of 1937, so my father had gone through a good “Soviet” school and already knew how to behave. For when he returned to the village and saw collective farm activists dragging a fine piglet out of his mother’s yard, he responded to a neighbor’s remark, “Mykhasko, what are you allowing?” in Russian: “*A ya zdes ne khozyain*” (“I’m not the master here”). After all, in that situation, resistance was futile and illogical: let these cruel human executioners-bandits, who call themselves communists, choke on that meat and fat… Because they would kill you. In a pack of wolves, you must howl like a wolf. But wolves don’t take bread from infants; on the contrary, they nurse them with their milk, while here are people worse than wolves. “Not people, but serpents,” as Taras Shevchenko wrote…

My father worked in the collective farm’s carpentry shop, fulfilling various orders for his fellow villagers; to this day, people still have his creations. He worked for his family, for his children… Then there was the war, the front line, from which a death notice came, but Mykhasko returned home alive, albeit with numerous wounds and a medal “For Courage,” yet he said that he had not killed PEOPLE… He also built a new house for the family, but then he fell ill and, after an unsuccessful operation in a Berdychiv hospital, died at the age of 45… If only it weren’t for those Siberias and those front lines… I was only three years old then and barely remember my father. I know I was very happy with him when we were building things together (I would help him with something); to this day, the smell of fresh wood shavings stirs me. When my father was leaving for Berdychiv, as if he had a premonition that he wouldn’t return, he said to the collective farm driver at parting: “Why did I have to spank Myshko?..” Later in life, I was thoroughly beaten during the Brezhnev era of arbitrariness and lawlessness—cunningly, basely, with forbidden blows, and not at all in a fatherly way…

My father left behind an orchard, an apiary, carpentry tools, a newly built house, and my mother with four children. She raised the children well (three other children had died during the difficult Stalinist times).

My mother is now 77 years old. Forty of those years were spent on the collective farm fields. My mother is like an image of Ukraine. In her youth, she had a beautiful voice, known throughout the village. On occasion, she would sing ancient, mournful Ukrainian pearl-like songs. And she still remembers a great many old songs, which she learned from her own mother, Todoska, who died young (I never knew my own grandmothers or grandfathers, and only barely my father; all my life, my guiding star has been my dearest and most sacred mother, Domka)…

My older brother Vitaliy had a great influence on my upbringing as a conscious Ukrainian. I remember, even as a preschooler, I could recite poems by T. Shevchenko from memory. Around the fifth grade, on my student geography map, I would outline Ukraine, separating it from the USSR with a pencil. I was greatly impressed by a book of selected poems by V. Symonenko, which my brother brought me from Kyiv, as well as the book “Ghost Hunters” by the famous writer-historian O. Gorbovsky. My brother gave me the idea that there were hypotheses about determining the future of humanity through mathematics. So, I thought, when I grow up, I’ll become a strong mathematician and calculate how to make our native Ukraine a free state… Such were the thoughts of a schoolboy. They were not destined to come true, because later, during the rampage of the Brezhnev reaction, I was thinking about how to free myself.

A turning point for me, a graduate of the Verbivka eight-year school, was 1968, when I read the disgraced novel “The Cathedral” by O. Honchar. I was also struck by the political events of that time—the occupation of independent Czechoslovakia by the “peace-loving” Soviet Army. With the pure soul of a teenager, I understood, despite the incessant propaganda, the wolfish essence of the USSR, the CPSU, and the great leader Lenin. To me, a village boy, it seemed that I was the only one who had figured this out, for after all, people wrote such beautiful poems about Lenin. Everyone shouted and spoke of Lenin as a god, and here I was with such thoughts: “It was he who destroyed independent Ukraine, the Central Rada, which was the flower of the nation, and he called it the ‘central betrayal’.”

I must have developed some kind of childish, schoolboyish neurosis, and I acquired the disease of “anti-Leninism,” “anti-Bolshevism,” and “anti-Stalinism.” No psychiatrist in the world could cure it… So, for carelessly confiding my thoughts to “well-wishers,” I was cunningly and forcibly sent “for treatment” (“Let the professor take a look at you”) to the Kyiv Regional Psychiatric Hospital (in the village of Hlevakha), at the age of 15, where I was subjected to the cruelest humiliation, abuse, torture, intimidation, and beatings by “patients,” and injected with powerful neuroleptics. The “attending physician,” psychiatrist Zhanna Arkadiyivna Koretska, after reading my graduation essay (for the 8th grade) about T.H. Shevchenko, said: “You have such thoughts, such thoughts…” and stared intently into my eyes. She probably didn't like that it talked about a future free Ukraine and about how “Judas’s blood will flow into the blue sea.” But it wasn’t about Jewish blood, but about ordinary traitors who sell out Ukraine, because such people also sold out Christ, so there could be no question of my anti-Semitism.

At that time, Koretska gave me clean sheets of paper and asked me to share more of my thoughts in writing, but I didn't reveal anything from my secret self…

In their “experiments,” the torturers in white coats went too far: I had to be brought out of a state of shock with insulin… That’s how they treated the disease of “Ukrainian nationalism.”

Subsequently, Z.A. Koretska, the “attending physician,” would write me a “ticket for life,” giving me the diagnosis: “Schizophrenia, simple type.” But with a self-protective addendum: “Has the right to enroll in higher educational institutions.” At that time, I didn't even know what “schizophrenia” was. I only remembered a quote from O. Dovzhenko’s “Diary”: “They say that war is an art. It is an art like schizophrenia or the plague…”

And so, at 16, I, an inquisitive village boy, was issued a “wolf’s ticket” for life, essentially placing me outside of society (according to Soviet psychiatric “laws,” a diagnosis of “schizophrenia” was “not subject to re-examination”). I found out what “has the right to enroll in higher educational institutions” meant as soon as I finished tenth grade: when they glanced at category 1, article 4 of the “schedule of diseases” in my military (“wolf’s”) ticket at the student polyclinic of the Taras Shevchenko Kyiv State University, they immediately showed me the door: “Look at him, he’s sick and wants to study at the university!”

I had to forge a medical certificate, which allowed me to take the exams, and having passed them successfully, I became a full-time student in the philology department of Kyiv University. There, in addition to Ukrainian philology, I specialized in the study of modern Greek language and literature. However, I wasn't even allowed to finish three years. In March 1974, a grand show trial of the third-year students took place in the philology department (the entire 3rd year from all departments—Ukrainian, Russian, Slavic—was present), where I was branded as an “enemy element” and a “nationalist.” The reason for this inhuman reprisal was that, as a first-year student, I had lived in the same student dormitory room with a fifth-year Ukrainian studies major, Vasyl Ovsiienko, and with his help, I became thoroughly acquainted with the outstanding work by Ivan Dziuba, “Internationalism or Russification?” (I read this work twice, taking notes). As the “commissar in a skirt” of the philology department, Margarita Karpenko (a professor, doctor of Russian philology!), declared: “You should have reported Vasyl, then you would have been on top of the world… But now we must fight for the purity of our ranks!” Most likely, the “private ruling” from the Kyiv Regional Court played a role here, where a closed trial of Yevhen Proniuk, Vasyl Lisovyi, and Vasyl Ovsiienko took place in December 1973. Among all of V. Ovsiienko’s numerous friends and acquaintances, I was brought in as the youngest “witness,” one who had never hidden his sympathies for his older comrade, an intelligent and honest man…

For the rest of my life, I will remember the merciless, “class-uncompromising words” of associate professor O.I. Bilodid (son of the vice-president of the Ukrainian SSR Academy of Sciences, Iv. Bilodid, the theoretician of the notorious “bilingualism” for the Ukrainian people) at the aforementioned theatrical trial, staged in advance and directed by the university's administration under the leadership of pro-rector Horshkov: “At this time, when Soviet people are smelting steel and mining coal, we are here talking about some Yakubivsky, who, along with Ovsiienko, decided, you see, to solve the Ukrainian question. He is a rotten sheep that should never be in our university!” (I am relaying this as I remember it. – M.Y.)

And professor of the history of Ukrainian literature, Valentyna Povazhna (may she rest in peace), said then no less famous words: “To live in the same room and not know what’s in your neighbor’s briefcase—that, forgive me, is not the Komsomol way!”

Subsequently, my path led me to Zhytomyr, where I got a job at the regional Komsomol newspaper. But after half a month, I was kicked out of there as an unreliable person. I had hidden my expulsion from the university, saying I had switched to a correspondence course. I was lucky to find a job as a loader at the Zhytomyr flax combine, but even there, the Zhytomyr KGB got to me: they offered me generous fees and a “bright future” to gather information among the workers and residents of the city. But I refused. Then they started orchestrating obstructions at work. I decided to resign and leave Zhytomyr. However, I only managed to get past the flax combine’s gate: the Zhytomyr police grabbed me, twisted my arms, and forced me into their barred “lunokhod” [police van], without any reason (I was sober), taking me to the pretrial detention center for a few hours. From there, they drove me “to Huyva”—to the Zhytomyr psychiatric hospital, where the doctor-executioner Pavel Vasilyevich Kuznetsov was waiting for me. This happened on June 13, 1974. Allegedly, on that day I had made an anti-Soviet speech near the Korolyov monument in Zhytomyr. In the reception room, I still tried to joke; when they were “filling out my form,” the “doctor” asked if I heard any “voices,” and I replied: “None, except the ‘Voice of America’.” But then it was no laughing matter for me, because the most horrific pages of my life began.

If you compare a death row cell with Kuznetsov's ward, that cell would probably seem like a resort: every day, powerful neuroleptics (haloperidol, trifluoperazine, aminazine, etc.), after which you can’t sit, lie down, or walk, you don’t know which world you’re in, and the torturer Kuznetsov asks: “*Chto, lamayet?*” (“What, is it breaking you?”).

I had no idea if I would ever get out of there: either they would kill me gradually, or they would really drive me insane, make me a cripple for life, and I was only 21. My brothers Vitaliy and Anatoliy turned for help to well-known people in Ukraine who knew me personally (I will not name them), but no one lifted a finger, even though they once patted me on the shoulder, saying, “You have talent!” That’s how they tormented and tortured me until September 5, 1974. I remember, before my discharge, the head doctor, Zhabokrytsky, asked: “A-ha, an ‘Ukrainophile’... You gonna go to the BAM [Baikal-Amur Mainline railway construction]?,” and the medical staff—nurses, orderlies, bone-crushing male nurses—gave me what they thought was a taunting nickname, “Independent Ukraine”: “There goes Independent Ukraine! Hee-hee…”

Before being released from this hell (I thought I would never get out of there at all; they even tied me to a bed in the same ward, next to a chronic, violently ill patient who screamed horribly day and night…), they gave me some unknown injections (they had been injecting me twice a day for three months). It probably took me seven years (and I still shudder at the memory) to exhale them from my system. When I was leaving Zhytomyr then, a responsible official from the Zhytomyr KGB, Borys Vasylyovych Zavalny, answered my question as to why they had tortured me so cruelly: “It was done for humane reasons!!” Another KGB agent warned me: “Be thankful you’re alive… Otherwise, we could do it differently: you’ll be walking along fences with a switch… herding geese.” No comment is needed here.

But I didn't give up. In Kyiv, where I arrived after recovering a little, I planned to carry out some vengeful political action, but the informers who were constantly watching me, following my every step, had me forcibly taken to the Pavlov hospital again. They called my own sister, Hanna, at her apartment (I was working as a manual laborer on a construction site at the time) and told her that I myself had called the ambulance, that I had, so to speak, lost my mind, because I had been walking around the dormitory naked, etc. True, in Kyiv they didn't torture me as much as in Zhytomyr, and the doctor, Danylo Abramovych Brandus (I've been told he now lives in the USA), even promised to clear me of all charges of being mentally ill: “I’ll fix everything for you, you’ll be grateful to me for the rest of your life!” But he didn't have the courage for more. He thought I was an anti-Semite, although that was just slander against me; before being forcibly confined here, I had even started to acquire Jewish literature and dictionaries to study Yiddish, and I had Jewish friends. Be that as it may, the refined Brandus once led me to a violent ward, locked with a key, with double-barred windows, where he rewarded me with several injections of powerful neuroleptics (previously, for “treatment,” he had prescribed some pills, which I simply threw into the sink or drain). In this ward, you had to watch how the violent, essentially insane people behaved: it was a horror! Such were the punishments in our civilized twentieth century in the land of socialism. So Brandus confirmed that I had indeed walked around naked and recorded it in my medical history: he wrote a vile lie, wrote what he was ordered to write. And he confirmed the diagnosis: “schizophrenic.”

When I later turned for help to Dmytro Pavlychko, the editor-in-chief of “Vsesvit,” who had known about me since 1970 and had been very favorably disposed toward me (“I see talent!” He even promised to publish my poems), he replied: “They've driven you to this... I'm not a doctor for you... Go on—right next door is the USSR State Prize laureate Borys Oliynyk—let him help you...” A similar conversation took place at the editorial office of the magazine “Vitchyzna,” where B. Oliynyk headed the poetry department; he, in turn, sent me to Ivan Drach, who sent me further. None of them helped me, not even with a kind word, while I, being in love with their poetry, where they swore their love for Ukraine, considered them true and good Ukrainian Sixtier intellectuals, knew countless of their poems by heart, devoured their works, and adored them.

Everyone shunned me. Where was I to go with the stigma of a “schizophrenic”? I was as lonely as a finger. Former classmates who had been my friends in my student years gave me a wide berth. The renowned classical philologist A.O. Biletsky and his wife T.M. Chernyshova (I took my modern Greek studies with her), whom I greatly respected and considered beacons among Kyiv’s Ukrainian intelligentsia, asked me not to visit their hospitable and extraordinary home, where the bright spirit of ancient Hellas wafted from unique folios, asked me not to call them anymore…

It’s no wonder that Vasyl Stus (as his friend and cellmate Vasyl Ovsiienko recalls), upon returning to Kyiv in 1979, felt a complete isolation from many of his former “friends,” who avoided him by a mile. V. Stus called this suffocating atmosphere among the Ukrainian intelligentsia a “*mertvechchyna*” [state of the living dead] and preferred to continue fighting for Ukraine's freedom, receiving a new, terrible sentence in a special-regime camp, rather than be part of this “*mertvechchyna*.”

In 1976, due to that isolation (I knew no future members of the Helsinki Group except for Vasyl Ovsiienko, who was imprisoned somewhere in Mordovia), I had to write a “confession letter,” because I understood they would kill me, that I would not come out of the psychiatric hospital alive or even a sane man the next time: Soviet psychiatrists would carry out any order from the KGB. I later learned that only two psychiatrists in the entire USSR had exposed the crimes and use of Soviet psychiatry for political purposes, for which they were imprisoned in Soviet concentration camps and jails. Among them was Semen Gluzman, for whom it would have been a disgrace to act towards me as Danylo Abramovych Brandus, a former psychiatrist at the Pavlov Hospital in Kyiv, had done… I am familiar with these words by S. Gluzman: “A psychiatric hospital is a very severe punishment, almost to the point of death.” Such people paid a heavy price for saving human honor and dignity.

So, in 1976, I wrote a “confession letter” with approximately the following content: “Admit me to the correspondence department of the philology faculty, reinstate me, I will no longer engage in nationalism.” The university’s pro-rector, Horshkov, demanded such a letter from me, and before that, a medical certificate from the psychiatric hospital stating whether I was fit to study at a higher educational institution… So, in the future, I decided to be “quiet, very quiet” (Y. Pluzhnyk), because they would destroy me. After all, it was only in films and deceitful socialist-realist writings that the nobility of the Soviet system and their leader Brezhnev were portrayed as messianic. Later, with the same bombastic, artistic zeal, they would curse that same Brezhnev, because the wind had blown in another direction…

With great difficulty, I was enrolled as a correspondence student at KSU, but that was enough for me to get a job as a permanent freelance correspondent for the newspaper “Kyivska Pravda.” But somehow I couldn’t play the role of a deceitful journalist, so in 1977 I managed to get a low-paying job as a researcher at the Museum of Folk Architecture and Life of Ukraine, where I still work today*. (* On September 17, 1991, my position was cut, as I was undesirable to the administration of the MNAZHU. – Author's note).

The museum is a large part of my life, the time of my spiritual and manly maturity. Perhaps those Shevchenko-style houses and windmills, as well as my interactions with honest, simple Ukrainian people during my research trips, helped me survive the Brezhnev-era obscurantism and also be very cautious of official, generously paid Ukrainian artist-patriots…

For me, the model Ukrainians became the peasant laborers, who preserve the pure wellspring of Ukrainian nationhood. At the museum, I essentially completed an academy of life studies, where many of my former thoughts took on a new form. However, I have not seen greater stupidity than in what would seem to be such a sacred place—among the leaders of this world-class cultural institution, their “inner circle.” But the same kind of people support them from above. This is how the pearl of Ukrainian culture—the Kyiv skansen—is perishing, and I have been fighting for its salvation for years with the third administration during my time here. Because the museum is also my salvation.

I have practically stopped writing poetry for 12 years. This coincides exactly with the year I got married. However, that was not the reason for my aversion to poetry. The main reason is the fight for the Museum. And although back in 1977 I adopted the aphorism of the 18th-century German philosopher Lichtenberg: “The only way for a fly to protect itself from a flyswatter is to stay on the flyswatter itself,” I never managed to become that cautious fly… As for my poems, I was put on a special list to not be published, as one poet informed me. Another poet wrote to me at the beginning of 1981 that my poems were “thematically outdated.” But can poems about love for Ukraine ever become outdated? Now, it seems, the theme of praising the party of Lenin, Stalin, socialism, and the “murderous” Banderites with their Derman wells, which the court poets-laureates wrote about back then, has become outdated. And now they have a new theme—an Independent Ukraine. And thank God it turned out this way. Praise Ukraine, but do it sincerely. The way the glorious poet-martyr Vasyl Stus glorified it, at the same time saving the honor of the Ukrainian poet in the dark, historically unprecedented era of Soviet totalitarianism, paying the highest price for it—his own life. And he did this not so that new “Stus-sycophants” would appear, but for the freedom of the talented and long-suffering Ukrainian people, who have now peacefully and lawfully won an Independent Ukrainian State, for which, during the “happy socialist reality,” people were thrown into prisons or psychiatric hospitals merely for the desire to achieve this.

I would like to look today into the eyes (if she is alive and well) of the “psychiatrist” Zhanna Arkadiyivna Koretska, who “for such thoughts” diagnosed me, an inquisitive teenager and an excellent student (at the age of 15), with “schizophrenia, simple type,” effectively crossing out my entire future life. I would like the “psychiatrist” P.V. Kuznetsov to try haloperidol on himself—twice a day for three months, as he experimented on me. And I would also like those KGB agents who ordered such “experiments”—“for humane reasons”—to try it, to go through it, and to feel it on their own skin. I don’t know if the Kyiv psychiatrist D.A. Brandus is alive and well in the USA, but God forbid that such “medical histories” be written about him or his children and grandchildren, or that they be “taught a lesson” with a “violent ward” and sulfur injections in the buttocks. I don't know if the

“pediatric” psychiatrist Halyna Ivanivna Lashchuk (as I remember her name) is alive and well today, who, not without consulting her colleague, the “psychiatrist” Bondarenko from Skvyra, Kyiv Oblast, for the “books I read” (“The Cathedral” by Oles Honchar – M.Y.), gave the order in the autumn of 1968, without my family’s knowledge and without any grounds, to send me, like cattle (though I threatened neither anyone nor myself with taking a life), in a dirty and disgusting “voronok” [KGB car] from the Bila Tserkva psychiatric dispensary, along with a deranged woman who screamed the whole way, to the infamous Hlevakha, into the arms of the already mentioned “psychiatrist” Z.A. Koretska. She was the one who issued me my “ticket to life”—after several months of torture, abuse, and “medical experiments” by the medical staff and their assistants, to intimidate and traumatize the “young nationalist.” After stuffing me with neuroleptics, they would tell my relatives: “You see, he’s having hallucinations…”

Is Komsomol organizer Mykola Zadorozhny alive and well, who, surely not without instructions from the relevant authorities, called an ambulance for me on October 21, 1975, at the premises of BMU-15 of the “Kyivprombud” Construction and Installation Trust No. 1? (I didn't even know about it, I was peacefully talking with my colleagues, where I worked as a tile-setter.) Suddenly, male nurses in white coats came towards me to “embrace” me and take me to the Pavlov Hospital... In general, that day had started happily for me: Professor A.O. Biletsky had lent me his coat for a while, as “well-wishers” had permanently borrowed mine. On that same day, about half an hour before being locked up in the psychiatric hospital, I had an unexpected meeting, or rather, my first and so far last acquaintance with the then-young and as yet uncompromised Vitaliy Korotych... That’s how Komsomol organizer Mykola Zadorozhny (!) looked after me, probably the same one who called my sister to say I had called the ambulance for myself. Well, this Mykola had served in the army on a submarine: he was a master of submarine affairs… Now, I suppose, he is also an “independentist.”

And as for me, for better or for worse, this idea dawned on me back in the 5th grade at Verbivka school, when, secretly from my classmates (I was the top student in the school), I would trace with a simple pencil on the map in my geography textbook, separating my native Ukraine from the detestable USSR.

I am very happy that my childhood dreams, like the dreams of many millions of Ukrainians who laid down their lives for this bright dream, have come true—on December 1, 1991, Ukraine de jure and de facto became an Independent State!!!

I, too, have paid dearly for this dream in my life: eleven months in psychiatric hospitals, over 500 injections of powerful neuroleptics… The scars on the veins of both my hands from the needles of the medical torturers are a reminder.

So many sorrows I have had to endure in my almost 40 years of life! May God spare anyone from such a fate! Such was the “school of communism.”

I want to end with the words of the brilliant Lina Kostenko:

І сум, і жаль, і висновки повчальні,

I слово, непосильне для пера.

Душа пройшла всі стадії печалі –

Тепер уже сміятися пора!

Lina Kostenko

April 15, 1992, Kyiv.

Journal “Zona,” No. 3, 1992. – pp. 191 – 201.

Characters: 25,380.

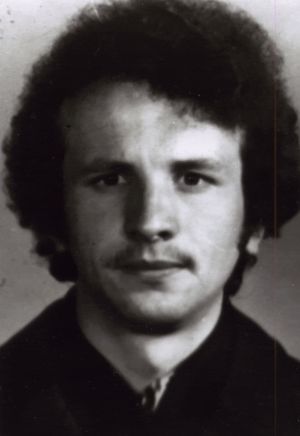

Photos: M. Yakubivsky in April 1974 and in January 2005.

Scanned and posted on the KHPG website by V. Ovsiienko on February 27, 2008.