(Magazine Zona, 1994. – No. 6. – pp. 163–180. Scanned and proofread on January 11, 2009, by Vasyl Ovsienko. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group).

The year before last, in the city of Inta in the Komi Autonomous Republic, maintenance workers in the service building of mine No. 11-12 (“Zapadnaya”) accidentally discovered a bottle sealed in a wall. It contained notes from the prisoner-builders who had constructed that building, that mine, and the very city of Inta, and who had been forced to “develop” the entire frigid North. (See: Syniuk, Mykola. “A Volynian Trace in the Cold Wastes of the North” // *Volyn*. Electronic edition, No. 894, January 29, 2009. http://www.volyn.com.ua. - Ed.). These letters to the future, written on random scraps of paper, were dated July 8, 1953. As one of their authors, I have finally decided to add my own authentic voice—not about the bottle, of course, as the bottle is self-explanatory—but about what lay beyond it.

At the zenith of totalitarianism, along both sides of the Kotlas-Vorkuta slave railway line, innumerable concentration camps bristled menacingly with barbed wire and watchtowers: the camps of Ukhta, Pechora, Inta, Vorkuta—places of immeasurable human suffering. Through these camps, millions of innocent people carried their cross, most often to their death, and their bones still moulder in the permafrost.

For those familiar with the history of the development of the North and Siberia, and even more so for the forced participants in that development, cities like Tayshet, Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Magadan, and Norilsk are invariably associated with those millions who were innocently tortured to death. Those cities also evoke images of desperate flashes of resistance, bordering on self-abnegation, against the Gulag’s genocide.

The year 1938. In the Vorkuta camps, one of the first political strikes took place, dubbed “Trotskyist” by the NKVD. After the strike was suppressed, 1,300 participants, at least half of whom were Ukrainian, were executed.

The 1948 uprising on the Khanovey camp route near Vorkuta was an act of protest: driven to despair by inhuman abuse, the prisoners went at the guards with their bare hands, seized the camp, and then, one by one, were lined up and shot (this event is described in I. Hryshyn-Hryshchuk’s short novel *Days and Nights near Vorkuta*. – *Dzvin*, 1991, No. 9).

Desperation, fueled by the unrelenting prospect of a slow death by starvation in the coal mines, led to the formation of “Pivnichne Siayvo” (“Northern Lights”)—an underground organization of political prisoners in “Minlag,” in the city of Inta. Between 1948 and 1950, “Pivnichne Siayvo” prepared for an uprising. It was exposed, and its organizers and activists were shot (P. Vosylevskyi. “The Slaves of the Communist Gulag Did Not Surrender.” – *Ratusha*, Lviv, May 14, 1992).

The mass political strikes in the early 1950s in the camps of Karaganda, Norilsk, and Vorkuta are considered milestones in their impact on the fate of the prisoners and of the Gulag itself. The strikes spread from camp to camp throughout the empire, and although they were mostly drowned in the blood of the striking prisoners, these organized actions shook the murderous Gulag system and significantly contributed to the Khrushchev administration’s decision to urgently empty the camps by releasing prisoners who were no longer willing to tolerate lawlessness.

Beginning in 1952, in the three main zones of the “Mineralny Camp” in Inta—the first, third, and sixth camp points, still reeling from the mass executions connected with “Pivnichne Siayvo”—a new group of like-minded peers began to form among the various Ukrainian communities. These were former underground activists, military personnel, students, and high school pupils before their conviction. The members of this group, to which the author of these memoirs had the honor of belonging (having managed to land in the Gulag straight from his school desk), were, because of their young age of 18-25, half-jokingly, half-seriously, called the student brotherhood. In addition to our age, shared circumstances, and camp solidarity, our young community was united above all by a sincere and constant focus on Ukraine—its rights, interests, history, and, of course, its future. Despite the bleak news from home, the brutal camp regime, and the forty-degree frost outside, not a hint of defeatist doubt ever entered our minds regarding the most important thing: the righteousness of the idea of independence. Moreover, we tirelessly contemplated how to hasten the arrival of that independence.

The student brotherhood began its public action in the camps with prolonged battles with the administration over what might seem a trivial matter: the right to receive and read Ukrainian books and periodicals. Previously, the Ukrainian printed word in the camps was officially considered contraband and was immediately confiscated. The Lithuanians, Latvians, and Estonians waged a similar campaign alongside us. In camp life, incidentally, Ukrainians always felt the warm and reliable support of the Balts, especially the Lithuanians. The book shipments we won soon became a unique national library circulating among us, greatly contributing to the spiritual uplift of many prisoners suffering from chronic depression. Some of our “students”—and I know dozens of such examples—in their free time after work and all the evening’s routines, individually taught school subjects to compatriots eager for knowledge, whose education had been cut short at the primary level by the war and early arrest. The camp youth yearned for knowledge.

Within a year, the youngest generation of prisoners—united, active, and not yet succumbing to the corrosion of indifference and social fatigue—gradually took on the unpleasant duty, rife with insults and unfortunate misunderstandings, of collecting monthly, and of course voluntary, contributions among the Ukrainian community for a fund to help sick prisoners in the medical block at the fifth [camp point]. We managed to collect up to several hundred rubles, as a miner's monthly earnings in captivity amounted to a paltry two-digit sum. Thus, when distributed in the medical unit, each sick brother received a symbolic 5-10 rubles—enough for tobacco and paper for letters. Nevertheless, this modest aid from the labor camps had a tremendous moral effect in conditions of total isolation, where the majority of the sick received no help or sympathy from anywhere. The camp KGB, of course, constantly tried to defame the very idea of mutual aid, as well as the volunteer collectors and the worker-“sponsors.” Eventually, financial transactions in the concentration camps were switched to a non-cash system, making financial assistance among prisoners impossible, but mutual aid continued in other forms.

Our young association was also forced to take on another important, and perhaps most distressing, public function on a voluntary basis: self-defense.

As is well known, political zones have always been systematically flooded with various criminal elements to terrorize political prisoners from within and morally corrupt them. There was no end to the attacks, robberies, and vile plundering. In the late 1940s, however, political prisoners, through their united efforts, managed to drive out the criminals, the so-called *vory* and *suki*, from the zones. At the same time, they reined in the overly anarchic political adventurers and, despite the understandable opposition of the Gulag administration, restored a sense of human morality in the zones. But with a high concentration of people in overcrowded barracks, there were always “strong personalities” who were disinclined to consider the presence and interests of others—people who did not behave, speak, or simply were not like them. Of course, direct provocations from the operations unit were common, especially in the realm of inter-ethnic relations. Everyday conflicts in a state of constant nervous tension flared up repeatedly. In such cases, readiness to stand up for the weaker, wronged person was always crucial. Simple human qualities such as compassion, solidarity, and objectivity were useful, as were steady nerves and, unfortunately, very often, equally strong and skilled fists. This type of ad-hoc activity, forced upon us by circumstances, consumed a great deal of energy and time, hindering our continuous efforts at self-education and preparation for something more important and necessary.

In the summer of 1955, at the second section of the zone, a guard from a watchtower, in the classic Gulag tradition, wounded two prisoners, Huzarevych and Levdansky, with a burst of automatic fire. At the initiative of the “students,” the second camp went on strike in protest. The “Minlag” administration, while deploying additional military guards to the zone, simultaneously agreed to meet the main demands of the strikers and went even further—releasing half the camp to a free settlement.

The thaw, brought about by the death of the world proletariat's leader, gave prisoners hope for further positive changes both in the Great Zone [the USSR] and in the small zones [the camps]. Individual and group releases became more frequent, especially for those imprisoned in the 1930s—we still found a few pre-war prisoners in the camps, the Ukrainian contingent of whom were called *Skrypnykivtsi*. But it was only after the turbulent and dramatic strike waves of 1952-56 that so-called visiting commissions from the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR appeared in the zones. They began to release political prisoners by the thousands, rehabilitating them, annulling fabricated convictions, or reducing sentences to time served. The question arose for each of us: what should we do upon release?

The majority of prisoners, weary from years of teetering on the edge of physical and moral exhaustion, nostalgically—and for every sensible and understandable reason—dreamed of a well-deserved rest among family and friends, far from the sites of their inhuman torment. The sick dreamed, in particular, of healing in their motherland. The old dreamed of at least finding their final rest in native cemeteries, beside the graves of their ancestors. The young fervently dreamed of continuing their education, but most often, undoubtedly most ardently, of starting a family. Despite all the valid caveats in this extraordinary situation, the measure of civic engagement in each individual case was clearly visible. Among the camp multitude, there was also no shortage of activists of the purest kind, noble Don Quixotes of the Ukrainian idea, capable of following the call of conscience to the very end, in spite of fatigue and even common sense.

In the camps of the northern Urals, where we were thoroughly isolated from the outside world by barbed wire, tundra, and distance, the situation south of Khutir Mykhailivsky was perceived with extreme sensitivity. It was clear that Moscow, despite the death of the Kremlin’s cyclops, had by no means renounced its great-power interests. The same oppressive course continued in Ukraine, which every living and conscious person had to resist in some way, and to some extent, often unconsciously, did resist.

Before our very eyes, so to speak, the unparalleled armed epic of the UPA [Ukrainian Insurgent Army] was reaching its heroic end. It was this struggle that had awakened us all and called us to civic action. Each of us, the young and the very young, had seen with our own eyes how the Ukrainian insurgents fought to the last bullet and how they died. We, students of a high school in Yaniv in the Berestia region, were regularly marched as a whole school to the pompous funerals of MVD and KGB functionaries killed in battles with the insurgents. Of their own volition, the students would also go to see the mutilated bodies of the insurgents, displayed in the open courtyard of the district KGB to instill fear and pity in the civilian population. In young souls, these spectacles produced not so much panic as a desire to somehow continue the cause of the fallen patriots.

Understanding the historical significance of the UPA’s feat, and bowing before the memory of the hundreds of thousands of insurgents, we at the same time could not fail to realize that in the new conditions—amid the triumphant bacchanalia of the KGB on the one hand, and social depression on the other—the struggle for the idea of independence had to be carried out by different methods. Nevertheless, we remained under the influence of OUN [Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists] ideology; the romance of the UPA still captivated us.

From our incessant calculations about future actions in our homeland upon release, the inevitable need for some form of organization or, as it was called in our circle, a union, gradually became clear. Without a union, without appropriately worked-out rules of the game, without a division of labor and responsibilities, it was impossible to think about effective activity under a foreign and hostile imperial regime, which was in no mood for jokes.

Our Ukrainian society, demoralized by continuous state terror, was at that very time, in the years 1956-60, despite the Thaw and the official—and of course, thoroughly false—condemnation of Stalin’s tyranny, experiencing a painful, critical period following the defeat of the UPA’s armed struggle. This period was marked by disorganization, disillusionment, nihilism, and outright political and national apostasy. Having dealt with the UPA, the great-power regime of the CPSU systematically, step by step, finished off Ukrainian society, burning out the OUN pride with a “hot iron,” and ruthlessly eradicating any tendencies toward freedom and independence. Ukraine was brought to such a state that it could not take advantage of the Thaw in the mid-1950s. The OUN underground still existed, but only in the form of separate local groups, preoccupied primarily with their own survival and no longer able to influence the course of events. We, therefore, had to rely exclusively on our own modest strength, our own spiritual drive, ingenuity, and endurance. There was no other path for our Union. The prospect of open, legal methods of activity, of demonstrative actions with an open visor, was very tempting. But common sense told us it was premature: the security organs of the totalitarian superpower, capable of striking fear into the entire planet, would not tolerate such audacity from us. Ultimately, the actions of our Union were, in their essence, completely constitutional: our people’s right to secede from the empire was proclaimed, at least in words, even by Stalin’s constitution, and we advocated for the implementation of this right.

In drafting a practical program of action, we assumed that some members of the union would disperse across Ukraine, as far east as possible, immediately after their release. There, after overcoming the inhospitality of the colonial authorities and the inevitable domestic difficulties, they would find a foothold and acclimatize. Our people did not seek cushy spots; they did not shun any work, as long as they could live and work on their native soil.

Another part of the Union would be forced, one way or another, to remain in Inta, in the northern Urals, either due to the regime of forced special settlement under commandant's supervision or for financial reasons. This second, Inta-based part of the Union, our organizational diaspora, was to serve as our base, our reserve, our deep rear, from which our theoretically planned actions were to be carried out. We were not pioneers in our intention to use the human and material resources of the exile for the needs of our homeland; such attempts had been made before. In 1952, a veteran of our liberation movement and a veteran of the Gulag, the late Mykhailo Soroka of blessed memory, paid for a similar attempt with his freedom, yet again. In Vorkuta, a group led by Oleksandr Vodyniuk (Ed.) had similar intentions.

Most of us were released with our convictions annulled, as the criminal cases of the “student brotherhood,” from a legal standpoint, were a shameless fabrication without any hint of illegal actions. We were blamed for words or thoughts that diverged from the regime’s dogmas, especially when it came to national or human rights. Most of the Ukrainian insurgents were also reviewed by the commission and released along with us—the accusation of banditry was not taken seriously even by the communists themselves, but for propaganda purposes, it was repeated until the ignominious end of the Soviet state.

One by one, we found ourselves outside the barbed wire—free! However, there was little reason or time for euphoria: a cause awaited us, one we had seriously devised for ourselves for the long haul. The mood of the newly “free” men was aptly captured in a spontaneous poem by our Union’s poet, Yaroslav Hasiuk:

Не такою тебе я чекав,

Пишнокрила, розкішна Свободо, –

Наче Мавка була серед трав,

А прийшла, мов горбань Квазімодо.

For some of us, freedom was restricted to the city of Inta by a special entry in our passports.

In our native lands, the returnees from the Gulag’s “other world” were met with the cautious and distrustful joy of their families. First and foremost, however, they were met by personal case officers and brazen swarms of informers of all profiles and specializations. Discriminatory sanctions, harassment, and repeated arrests soon followed. Even some of our relatives, our cousins, and our former classmates and fellow students, being very cautious and proper, would cross to the other side of the street during accidental encounters. On the whole, however, there was no doubt that Ukrainian society objectively needed our leavening agent, the ferment of groups like our Union. It turned out there were such groups in almost every region; they were doing something, but due to self-isolation and inexperience, they very quickly fell into the KGB’s trap and ended up in the Gulag. Our concept of the struggle for independence primarily involved explanatory work, disseminating desperately needed information, the lack of which was simply suffocating society. Therefore, from our very first underground steps, we took measures to acquire duplicating equipment, and ultimately, a printing press. In this regard, we soon had a stroke of luck: a man whom we desperately needed, Vasyl Buchkovsky, joined the Union.

The life story of this man is largely typical for activists of the 1950s movement. Buchkovsky, a peasant’s son, was a successful student at the Lviv Polytechnic Institute, while his heart and thoughts were with the last of the insurgents. For belonging to a patriotic student group and for producing and distributing anti-regime leaflets in Lviv, Buchkovsky was arrested in 1952 and sentenced to 25 years in prison. Buchkovsky spent over four years in the camps of Tayshet, fully comprehending the depths of socialist legality and humanism. Like all of us, Buchkovsky was released from prison ahead of schedule in 1956. He settled in Ternopil, worked, and got married. But a year later, the security watchdogs administratively, without explanation, forced him out of Ukraine—a secret supreme decree was in effect, which gave the KGB the right to expel citizens from the republic within 24 hours without ceremony, specifically targeting formerly convicted individuals, "known nationalist ringleaders," a category into which anyone could be placed. Buchkovsky was forced to move to Inta, where he threw himself headlong into the affairs of our Union.

With V. Buchkovsky’s arrival in Inta, our plans and dreams of a printing press—initially modest and primitive—entered the implementation stage. For conspiratorial reasons, we had to abandon the search for ready-made fonts. The task was to make both the fonts and the other printing equipment ourselves. We had to use the letters from a typewriter as a basis for our first font—through matrixing, we cast about two kilograms of type, and later more. The headline letters were carved by hand on babbit blocks. Simultaneously with the printing of several small runs of leaflets using the typewriter font, work was underway on creating standard academic-style fonts using zincography, a process we had mastered by then. Despite his disability, acquired during a previous investigation, and the fatigue from working for his daily bread, V. Buchkovsky worked with inspiration, demonstrating the skill and ingenuity of a highly qualified engineer and a selfless patriot. “The Decalogue” and “The Carpathians Accuse” were printed with the academic font. Soon, arrests began, as did surveillance and the moving of the printing press from one apartment to another.

The first parcel of printed leaflets from Inta traveled south in the fall of 1957. Soon, the leaflets were distributed in certain towns and villages in the Kirovohrad, Poltava, and Rivne regions—they were scattered on streets, in yards, and pasted on poles and fences. The deed was done—we had crossed our Rubicon. As for our idea of surveying our readers, we did not dare: security rules did not recommend it. Our investigators later swore that there were cases where people, after reading the anti-Soviet leaflets, brought them to the authorities themselves. Perhaps. In some cases, disapproval could also be dictated by ideological motives. But above all, I am convinced, the reports were stimulated by the impenetrable fear of our native Ukrainian everyman. This fear, instilled by well-known methods from generation to generation, is palpable even now, paradoxically, in the era of independence.

Thirsting to the very core for a word of truth about Ukraine, we, no doubt, boyishly exaggerated the importance of that word in the social process. For even without our leaflets, the people knew their past and were well-oriented in current events. Our people had a cherished thought about their future, only the “elder brothers” deprived them of the legitimate opportunity to express that thought without reservation. But they did express it, decisively and unanimously, on December 1, 1991.

Воля народам! Воля людині!

ГРОМАДЯНИНЕ!

Чи зробив Ти висновок, що дав українському народові жовтневий переворот 1917 р.?

Він зліквідував здобуту народами внаслідок повалення царизму волю, придушив молоду Українську Народну Республіку, принісши Твоєму народові ще гірше рабство, ніж було царське; він спричинився до загибелі кращих Твоїх братів і друзів, до занепаду української культури і до знищення Твого добробуту.

Чи згоден Ти і надалі терпіти більшовицьке ярмо?

Українські революціонери.

1957 р..

Прочитай і підкинь непомітно другому.

Воля народам! Воля людині!

КОЛГОСПНИКУ!

Щоб і надалі утримувати численні зграї внутрішніх і закордонних дармоїдів, Твої визискувачі-комуністи поставили перед Тобою ще одну вимогу – наздогнати США по виробництву м’яса, молока і масла.

П а м’ я т а й:

продуковане Тобою м’ясо, молоко і масло йде не для українського народу, не для поліпшення Твого добробуту, а для зміцнення московсько-більшовицької тюрми народів;

Україна використовується як сировинна база, з якої колонізатори вивозять усе, залишаючи народ на півголодне існування;

ні Ти, ні Твоя сім’я, ані Твої потомки не спроможні залити пельку ненажерному ворогові;

тільки у власній, економічно та політично незалежній державі український народ повністю користуватиметься багатствами рідної землі і плодами своєї праці.

Тому ставай під прапор боротьби за волю України і за справедливий соціальний лад.

Годі терпіти кремлівське ярмо! Годі бути рабами! Український народ, як і всі народи, має право на незалежність.

Пора сказати московсько-більшовицьким загарбникам:

Геть з У к р а ї н и!

Хай живе Українська Самостійна Соборна Держава – єдина запорука селянської волі!

Українські революціонери.

1957 р.

Прочитай і підкинь непомітно другому.

As was to be expected, the regime, stronger at that time than ever before, slightly rejuvenated by Khrushchev’s half-reforms, could not allow an illegal group to operate with impunity under its nose, pestering it with talk of Soviet colonialism and Ukrainian independence. The republic's Committee for State Security in Kyiv properly assessed the Union’s debut—our little calf’s attempt, so to speak, to kick their oak tree—and immediately opened a case, mobilizing its best agents to neutralize the clumsy “revolutionaries” with their homemade printing press. We confidently believed we could withstand the KGB’s first and second attacks, and then see what happened. In practice, it turned out a little differently.

Well-known KGB agents from Ukraine, burdened with considerable seniority and involved in almost all the repressive orgies since 1944, took on the Union. Given their unique status and the unusual experience gained in the permanent war against the Ukrainian people, the Kyiv KGB agents treated their Moscow and especially Minsk colleagues from the same agency—no angels themselves—with condescension, as if they were rookies.

The Committee for State Security of the Ukrainian SSR was then headed by General Nikitchenko, a man so polite, so humane: now, he would say, are not those times; now there is no social basis for lawbreaking; your Union is an exception. A lie, of course: parallel to our Union, the committee headed by Nikitchenko was handling dozens of cases of the Fifties generation, and the Sixtiers were already waiting in line. Wasn't it he, this false advocate of legality, as chairman of a judicial troika in 1938, who sentenced General Gorbatov? The latter’s memoirs mention a sarcastic young judge in a naval officer’s uniform with the surname Nikitchenko.

Major Kaliko. A typical janissary. He couldn't string together two sentences in Ukrainian, a fact he openly flaunted with defiance, considering his dirty janissarism a model of internationalism. It's simply amazing which of the major's qualities was considered his trump card in the KGB's service—readiness to face bullets, brutality, Ukrainophobia?

Lieutenant Colonel Guzeev. His main specialization was the Ukrainian liberation movement. He also dealt with Romania, went on business trips there, and boasted of his knowledge of the Romanian language—in the Kyiv KGB, there were also specialists in the affairs of Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, but the republican committee in Kyiv had a constant anti-Ukrainian focus. Guzeev was involved in the cases of R. Shukhevych, Yu. Shukhevych, D. Husyak, and H. Dydyk. Some knew Guzeev as a sadist capable of physical abuse; others, like Yu. Shukhevych himself, singled him out from the general brutality of the KGB as more or less proper, if one can speak of the propriety of a KGB agent. In reality, Guzeev could be both “proper” and “improper” at the same time, depending on the circumstances and the identity of the victim.

Other stalwarts of the republic's KGB who also dealt with the Union: Colonel Pyvovarets, Colonel Zashchitin, Lieutenant Colonel Shevtsov, Lieutenant Colonel Ionov. To arrested Ukrainians, these comrades, for tactical reasons, of course, presented themselves as Ukrainians too. They were well-versed in the flaws of the Ukrainian character and spoke our language quite well, peppering their speech with abundant Galician dialectisms for greater effect. However, it was precisely the bearers of Russian surnames among the Kyiv KGB agents who spoke Ukrainian the best. Falsely emphasizing their belonging to the Ukrainian people, they in fact felt themselves to be consummate Russians. Their philosophy regarding Ukrainianness was fully encapsulated in the well-known postulate of Valuev: "There was not, is not, and cannot be." They blamed the intelligentsia above all for the resilience of the Ukrainian idea and fiercely hated it. The Kyiv KGB agents, for example, considered Hryhoriy Kochur to be the greatest and most influential nationalist in Inta—the very same one: the brilliant polyglot translator and poet, the pride of our literature, a former innocent political prisoner who at that very time was working on compiling an anthology of Slovak poetry. And in Kyiv, it turned out, inveterate nationalists were then rallying around Maksym Tadeyovych Rylsky, who, in the opinion of the KGB, was a bigger Banderite than Bandera himself. Can you believe it? And we, mindless dolts, did not know where to look for like-minded people and allies.

The republic’s KGB directorate received our leaflets from all the places where they were distributed. Therefore, an operational-investigative group was immediately created within the committee, which began to work at an accelerated pace. Several working versions were put forward. Experts from among well-known specialists were brought in for collaboration. What was missing, for now, was at least one “tongue” [an informant].

The experts asserted, in particular, that neither during the German occupation nor after, nor in general since the time of Schweipolt Fiol and Ivan Fedorovych, had any printing presses with similar fonts been recorded on either side of the Dnipro. They claimed that the content, ideological direction, and even the linguistic features of the texts corresponded to one of the contemporary trends in the Ukrainian movement, the main breeding ground of which was the western regions. Therefore, the distributors of the malicious, hostile leaflets in the Kirovohrad and Poltava regions could primarily be people from those very regions. Among these people, special attention was paid to former political prisoners, returnees "from there," who were scattered like dense clusters throughout all the eastern regions.

Therefore, in the Poltava and Kirovohrad regions, almost all citizens who had the misfortune of being born in the "reunified" and "liberated" regions of 1939 were placed under close surveillance. A series of interrogations, searches, and damning anti-Ukrainian rallies and meetings were conducted. Banderaphobia was inflated to its extreme limits. The curators of the case were high-ranking representatives of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, headed by Comrade Shelest. One must say, the imagination of the republican leadership ran wild: indeed, a new underground had come to light, and at a time when they had not yet fully dealt with the old one. Two years passed in this manner.

In this situation, the republican KGB directorate, with the blessing of the Central Committee of the CPU and the prosecutor's office, committed another lawless act—imprisoning several dozen more or less well-known former political prisoners without trial, either by reinstating old sentences or through a farcical trial.

I name from memory only those I knew: M. Voloshchak, St. Soroka, Ye. Horoshko, Muroshko, R. Pysarchuk, V. Sorokalit, R. Duzhynskyi. As a precaution, V. Horbovyi, M. Soroka, K. Zarytska, and M. Stepaniak were brought from their places of imprisonment to the Kyiv KGB isolation cell.

In the course of the investigation, the KGB repeatedly transgressed its own laws, because, as is well known, laws are not written for enemies of the Soviet government. For example, an investigation could last for years—the prosecutor's office set no chronological limits, although they are stipulated by procedural legislation. Several arrests were made in violation of this legislation—solely on suspicion or based on the testimony of a single person. Biased and arbitrary reclassifications of the articles of indictment also diverged from the law, although the content of those articles of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR, primarily Articles 56 and 62, was formulated at the KGB's request to give the latter complete freedom.

As expected, our people, members of the Union, also came under close surveillance. This included Yosyp Slabyna, a resident of the village of Pantaivka in the Oleksandriya district of the Kirovohrad region, one of the active distributors. There was nothing supernatural about the surveillance: the KGB is always watching someone. But our people, in extreme circumstances, often lose the ability to think and act logically. Moreover, they sometimes press on with unjustified, occasionally irresponsible initiatives. For Slabyna, for instance, the Kirovohrad region was not enough—he took it into his head to bless other regions with his leaflets. He confidently boarded a train at the Znamianka station and set off, carrying several hundred leaflets, with no idea that a team of very self-assured and resolute citizens was boarding the same car right behind him. They blocked the car and began a search on the move, explaining to dissatisfied passengers that they were looking for money from a recently robbed bank. In this banal way, the KGB managed to identify a person who was undoubtedly involved with the leaflets—in short, they stumbled upon a “tongue.”

This was the beginning of our downfall. The location of the printing press could now be localized to the city of Inta in the Komi ASSR, from where the detained Y. Slabyna had arrived in the Kirovohrad region two years earlier. The radius of surveillance and searches could be narrowed to Inta and its residents. In Inta itself, one after another, wholesale searches and interrogations of people were conducted based on their old camp records. As the KGB agents joked, Inta, and with it Vorkuta, were temporarily placed under the jurisdiction of Kyiv. But searching blindly could have gone on for another year. Meanwhile, the printing press was working at its full homemade capacity. The printing technique was being perfected, and new texts were being prepared.

At this time, however, the KGB managed to stumble upon another of our comrades in the same Kirovohrad region. His ideological reorientation, given the danger of arrest, reached its apogee and pushed him to a full confession at the very first preventive interrogation. (This was Anatoliy Bulavsky. – See: Khrystynych, Bohdan. *On the Paths to Freedom. The Underground Organization “The Union” (1956-1959).* – Lviv, 2004. – pp. 57, 112-113). The dear comrade told everything he knew and suspected during the interrogations, providing detailed descriptions of the initiators known to him. Thus, in Kirovohrad, they learned about the existence of the Union, its goals, and the probable location of the printing press. Some by plane, some by “Stolypin” [prison railcar]—they began to bring the exposed members of the Union to the “mother of Rus' cities.” And on this occasion, each of the arrested could think, as I, for example, thought: "So, Kyiv, receive your unfortunate stepson, who dared to imagine turning you from a 'stinking pit' (Lesia Ukrainka) into the capital of a free, independent state." Soon, the arrested members of the Union were, as a privilege, registered in the center of Kyiv, in a prestigious quarter at the address: 33 Volodymyrska Street. It was the summer of 1959.

De facto, the activities of the Union ceased at that point. The printing press still printed a few things, but none of the remaining members dared to distribute what was printed.

I will not recount the course of the investigation: for the history of social thought, it is of secondary, derivative importance, in my opinion.

Having received information about the quantitative and qualitative composition of the Union, the investigative department calmed down considerably: the theory of a large, well-organized underground, modeled on the OUN, could be taken off the agenda. Now they could leisurely inflate their own importance before the higher authorities.

I will focus on a few characteristic situations.

On the seventeenth or eighteenth of October 1959, I had a confrontation of secondary importance with a witness. As befits the situation, the witness, entangled by his own cowardice, was at once deeply frightened and ashamed. It was hard to believe that this man, a former political prisoner, had, around 1954, dared to join four comrades in an "escape attempt," that is, to run into the taiga under the bullets of the guards, walk from Kozhym to Pechora, only to stumble into a special ambush there and be returned under convoy to his native "Minlag" with the resounding fame of an escapee. Apparently, bullets aimed at a person are not the decisive argument for their state of mind. (This refers to the escape on the night of October 4-5, 1954, of seven political prisoners from the work zone of mine No. 11 through a 40-meter tunnel dug from a ventilation shaft. It took 6 months to dig. Six of the escapees were caught, but Semen Soroka reached the Inta station and took a Vorkuta-Moscow train to Ukraine. In January 1956, he was arrested and continued to serve time in Vorkuta. – From the book: Khrystynych, Bohdan. *On the Paths to Freedom. The Underground Organization “The Union” (1956-1959).* – Lviv, 2004. – pp. 25-26).

The investigators leading the confrontation, Guzeev and, I believe, Kaliko, were acting like it was their birthday; they were in high, celebratory spirits that in no way corresponded to the significance of this event in the case. I had never seen them like this before. Then again, they were great masters of bluffing, true professionals. But no, this time the joy was unfeigned—sincere and boisterous.

“So what’s the matter?” I cautiously asked Guzeev when the confrontation ended and the completely exhausted witness was finally led out of the interrogation room.

Lieutenant Colonel Guzeev came very close to me. I was sitting in my designated chair in the corner of the room, opposite the window, "in formation." Guzeev liked such close approaches; it was one of his forms of pressure on the interrogated.

“Your supreme leader is no more!” the lieutenant colonel exhaled his joy maliciously, almost in my face, so distinctly that I immediately understood everything.

“He died?!”

“Men like him don’t just die!!!”

“What happened to him?”

“Found dead yesterday. Now, of course, you’ll say it was our work...”

“Of course, only yours, who else would it be!”

“Oh no, I beg your pardon, there are two versions: either Oberländer killed him, or the murder is the result of fighting over the feeding trough. You think wrongly about us, and this is the mistake of all anti-Soviets. If we were concerned with his elimination, nothing would have been easier. But we, unlike you, are against any terror, individual or mass...”

Throughout that week, my own prisoner’s troubles seemed like a trivial game to me against the backdrop of this fresh all-Ukrainian wound, inflicted so unexpectedly and vilely. We, unfortunately, do not know how to protect our leaders, and we only grasp their true value after their senseless deaths, which could have been avoided.

Every now and then, the investigators tried to humiliate my dignity with attacks related to my Polissian origin, accusing me, among other things, of betraying Belarus: you are, they would say, a Belarusian, so you should have fought for the independence of your Belarus and not meddled in our Ukrainian affairs—we can sort things out here without you. For a while, I remained silent, and then I explained to them that I am not a Belarusian, but a Ukrainian, and that my Berestia region is also not Belarus, but a part of Ukraine, given to the Belarusians as pasture by Stalin's will in 1939. When asked why it was given away, I explained: to compensate Belarus for the loss of the Smolensk region and thus to complicate relations between Ukrainians and Belarusians.

The last conversation on this topic took place after a long, exhausting interrogation. The interrogation was about the printing press, of course. The main demand in those interrogations was always the same: hand over the printing press, and the case is closed. My tactic in the investigation, not flawless, of course, consisted in a complete denial of everything that had any relation to the real facts. I was later forced to confirm some things, when a briefcase with fonts, which I knew well, was triumphantly and victoriously placed on the table before my nose, and there was a sudden need to attribute some things to myself in order to protect others who were still at liberty. But this happened in the second year of the investigation, in the summer of 1960.

My interrogators and I felt tired after the interrogation. And then Guzeev, my friend, brother, comrade, and wolf of Bryansk at the time, said good-naturedly to his KGB colleagues, Zashchitin and Kaliko, who were constant assistants at more important interrogations and confrontations:

“I know how to make Pan Vlodko talk—we just need to put the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on the annexation of the Berestia region to the Ukrainian SSR on the table in front of him. The case will then go like clockwork: Pan Vlodko will give up the printing press, disarm ideologically, and the case will be closed. Isn’t that right, Volodymyr?”

The investigative "team" stared at a large map of the Ukrainian SSR that covered the entire wall, with abundant marks in colored pencils in the western region. The Berestia region was, of course, not part of the Ukrainian SSR. The Berestia region was altogether outside the frame of the map.

“Sooner or later,” I said, “the Berestia region will have to be reunited: it is illegally and unjustly under the BSSR!”

“You seem to be an intelligent man, yet you talk nonsense,” Zashchitin rattled on.

“The Soviet government never revokes its decisions, so get these fantasies about the Berestia region out of your head and stop confusing people!”

“Oh no, sirs and comrades, the trouble with the Berestia region will be inevitable until it obtains its proper status according to its rights!”

Summing up the case of our Union, Colonel Zashchitin said at the end of the investigation:

“You worked well, unbelievably so, and you were aiming for even more. If the Union had acted in the name of the Soviet government, it would have deserved the highest gratitude. But you acted against the Soviet government. Therefore, you will receive what you have earned. The people do not forgive crimes.”

Our story was approaching its finish line. The Union ceased to exist with the arrest of the majority of its members. The printing press was also arrested and, with due formalities, was sent for scrap.

We were tried for treason. The treason, in the opinion of the investigators, prosecutors, and judges, consisted in the fact that as members of the Union, a counter-revolutionary, nationalist, anti-Soviet organization, we tried to separate Ukraine from the USSR and, on top of that, to restore capitalist, bourgeois order. Well, as for Ukraine, that’s the holy truth: we were for a Ukrainian Independent and United State. But as for the restoration of capitalist order, good heavens, we never thought of that; our ideal was freedom. So, in this case, we are dealing with ordinary Bolshevik accusatory demagoguery.

The judge of the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR, Zbarazhchenko—in a Ukrainian embroidered shirt, speaking Ukrainian. The prosecutor Yankovsky—without an embroidered shirt, on behalf of the Ukrainian SSR.

The first group convicted in the Union case in Kyiv in 1960: Kyrylo Banatsky sentenced to 15 years of imprisonment, Yosyp Slabyna—to 7 years, Anatoliy Bulavsky—to 10 years, later pardoned after serving three, Stepan Olenych—to 3 years, Mykola Riabchun—to 3 years.

The second group convicted in the Union case in 1960 in Kyiv: Yaroslav Hasiuk sentenced to 12 years of captivity, Volodymyr Leonyuk—to 12 years, Bohdan Khrystynych—to 10 years, Volodymyr Zatvarsky—to 8 years, Yaroslav Kobyletsky—to 5 years of captivity.

Approximately the same number of Union members remained unprosecuted: in 1960, after the crushing of the Union, the KGB, for some reason, was not interested in inflating our case.

The trial of the Union, it seems, marked the end of the Khrushchev Thaw, at least in domestic affairs—just a year later, for a case similar to ours, Levko Lukianenko was sentenced to death, and B. Hrytsyna and Koval were indeed executed.

Finally, one more memory. One day, Lieutenant Colonel Guzeev led the author of these lines to the barred window of the interrogation room and pointed to a large red flag proudly fluttering on one of the roofs in the area of St. Sophia’s Square. Guzeev's bass voice still rings in my ears:

“I’d bet my head—your yellow-and-blue flag will never fly over Kyiv!”

Comments, as they say, are superfluous.

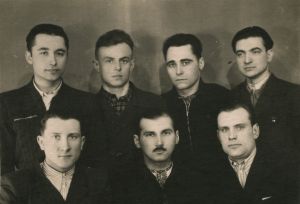

Photos: Volodymyr Leonyuk.

Objednannia56. Standing: Bohdan Khrystynych, Andriy Kushka, Bohdan Kulyk, Yaroslav Budzanivsky; sitting: Volodymyr Leonyuk, Bohdan Stefaniuk, Yaroslav Ivanchenko, Inta, March 19, 1956, archive of V. Leonyuk.

ObjednKhr-Has-Zat-Vol1: Bohdan Khrystynych, Yaroslav Hasiuk, Volodymyr Zatvarsky, Volodymyr Leonyuk at the fresh grave of Halia Hasiuk (1999), archive of V. Leonyuk.